Discorhabdella pseudaster, Vacelet & Cárdenas, 2018

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4466.1.15 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1BCC4BD8-A168-408A-8DFD-407DFA44C91D |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5979497 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/7A38D22E-7F01-47F8-869B-24DAF8217B18 |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:7A38D22E-7F01-47F8-869B-24DAF8217B18 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Discorhabdella pseudaster |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Discorhabdella pseudaster View in CoL n. sp.

Holotype. MNHN-IP-2015-1083, station DW 4788, Warén dredge, 22/01/2017, Banc du Geyser, 12°22’ S, 46°25’ E, 346–349 m depth, rocks and pebbles. Field# PMG 0 5, coll. C. Debitus, ethanol 95%.

Description. A minute, incrusting sponge, 4 x 2.5 mm and 200 µm thick, hispid ( Fig. 2 A View FIGURE 2 ). Color grayish white alive and in alcohol. No visible aperture. A stoloniferous calcified octocoral, possibly Scleranthellia (Gary Williams, pers. com.), is growing on the same rock.

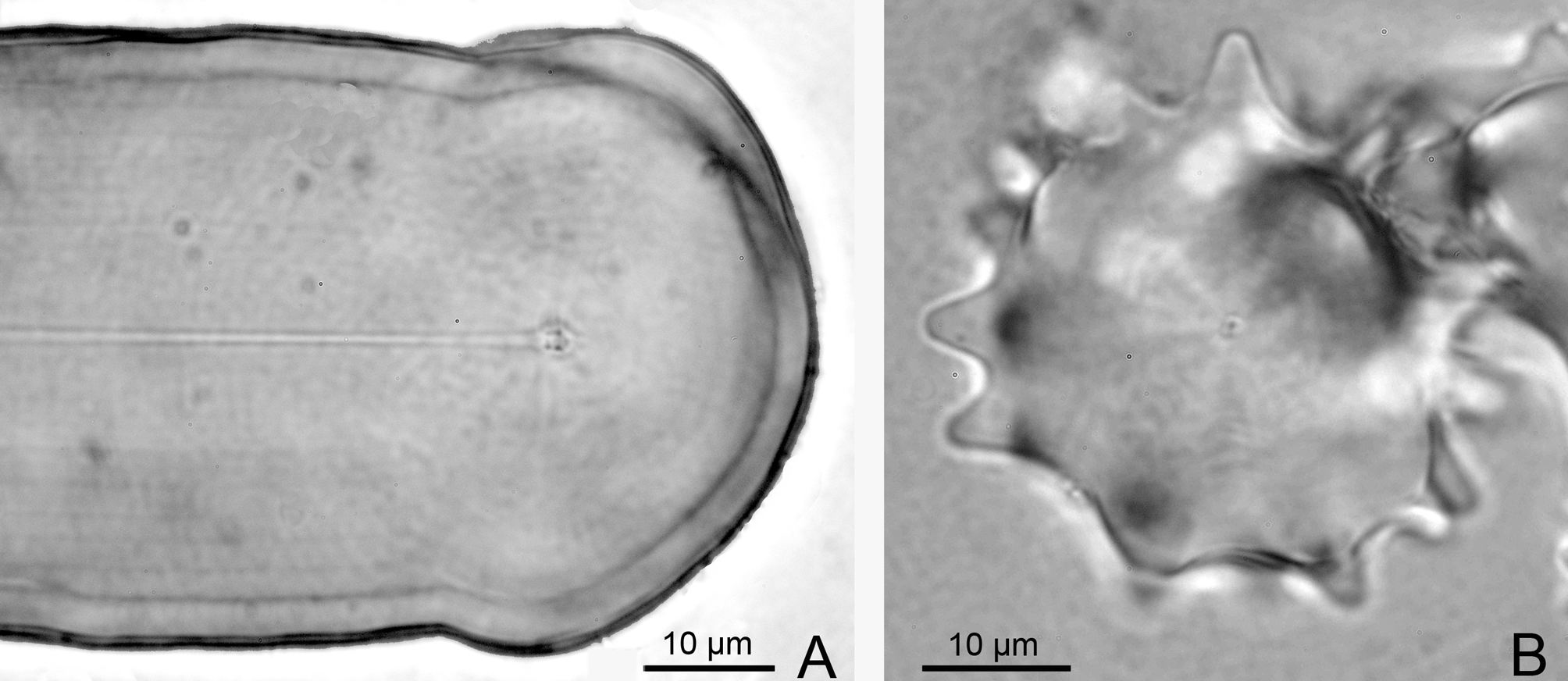

Skeleton. The skeleton is made of long styles with a barely inflated head bearing low, round tubercles. These styles are disposed vertically on the substratum and give the long hispidation. They are surrounded by smaller tylostyles irregularly arranged, sometimes forming poorly defined bouquets. Pseudoastrose acanthostyles are arranged vertically, with the head on the substratum. Pseudoasters and isochelae are dispersed in the whole choanosome. Spicules. (1) Subtylostyles ( Fig. 2 B View FIGURE 2 ), straight or slightly curved, with a barely tuberculated head, all broken in the spicule or skeleton slides. Axial canal ending in a small vesicle in the head (not divided), although faint, radiating darker lines could be seen ( Fig. 3 A View FIGURE 3 ). Maximum length of the broken spicules: 600 µm, diameter 40–56 µm near the base.(2) Tylostyles ( Fig. 2 C View FIGURE 2 ), straight or slightly curved, with a well-marked oval head, 240– 370 x 9–10 µm.(3) Pseudoastrose acanthostyles ( Fig. 2 D–F View FIGURE 2 ). Spine-like rays of the head obtuse, those of the end of the shaft generally more acute. Total length 35–45 µm, diameter of the head 35–40 µm, shaft 20-25 x 12 µm with spines at the extremity. Axial canal barely visible by transparency (not divided in the head), although faint, radiating darker lines could be seen in the head ( Fig. 3 B View FIGURE 3 ). Some rare spicules, likely juvenile, are a little smaller (e.g. 28 µm in length), and have more acute spines.(4) Pseudoasters ( Fig. 2 G–I View FIGURE 2 ), similar to spherasters, very abundant, 12.5–18 µm in diameter, with conical, sharp spine-like rays, 2.5–4 µm long. No visible axial canals in the spines.(5) Unguiferous cleistochelae ( Fig. 2 J View FIGURE 2 ), small, 12–15 µm. Shaft straight, 4 or 5 teeth nearly in contact, often with the end on one side blunt and the other slightly indented. The shaft bears a conspicuous lamella, attached by a part of its length, similar to a hatchet. The free part of the hatchet is most often directed towards the nonindented teeth, but the opposite case has also been observed.

Etymology. From Latin pseudo (meaning false) and aster.

Remarks. The presence of chelae makes this sponge a Poecilosclerida . This minute sponge clearly belongs to the genus Discorhabdella by its shape, skeleton and especially the diagnostic club-shaped pseudoastrose acanthostyles. Unfortunately, the unique specimen is too small to allow obtaining sequences, so the affinities between Discorhabdella and Crambe remain likely ( Maldonado & Uriz 1996), but not formerly demonstrated.

It is rather puzzling to find “aster” spicules in a poecilosclerid, which moreover have the same position in the skeleton as true asters in non-poecilosclerid encrusting sponges (e.g. Spirastrellidae, Chondrillida or Tethyida). The true nature of these asters is questionable. It is essential in taxonomy and phylogeny to use homologous morphological characters, and that is not always obvious as clearly shown by Fromont & Bergquist (1990) with the example of sigma microscleres or acanthose megascleres. Here, the most likely explanation is that the “asters” derive from the pseudoastrose acanthostyles with reduced shaft typical of Discorhabdella by complete loss of the shaft. The presence of “asteroid” corpuscules somewhat similar to asters have been described in two other members of the family Crambeidae , Crambe tuberosa Maldonado & Benito, 1991 , and Crambe chilensis Esteves et al., 2007 ; these spicules, which in C. tuberosa have axial filaments in the actines, were interpreted as developmental stages of desmas, otherwise present in Crambe spp. ( Maldonado & Benito 1991; Uriz & Maldonado 1995; Maldonado & Uriz 1996).

*For D. incrustans , measurements by van Soest (2002) from the holotype.

** From Hinde & Holmes (1892): p. 194, Pl. VIII, Fig 29.

*** Tentative identification by Łukowiak (2015) from one Eocene spicule.

It has been suggested that pseudoastrose acanthostyles are polyaxial spicules, on the basis of SEM observations ( Uriz & Maldonado 1995; Maldonado & Uriz 1996). However, in our opinion, the presence of axial canals in the spines of the head of the pseudoastrose acanthostyles remains doubtful: in a few immature spicules, some actines of the head show a very small hole at their end ( Fig. 2 E View FIGURE 2 ), but a canal could not be seen in transparency under a light microscope in the actin of mature spicules, while the axial canal of the shaft of the same spicules is clearly visible. Similarly, the subtylostyles with a slightly tuberculated head show by transparency a clear axial canal ending in a vesicle in the head, without division. However, it must be noted that from this vesicle, there are very faint radiating lines, which could indicate remains of axial filaments present during the spicule formation ( Fig. 3 A View FIGURE 3 ). The same very faint radiating lines are barely visible in the head of pseudoastrose acanthostyles ( Fig. 3 B View FIGURE 3 ). It is also possible that these extra spines and bulges are produced by secondary axial canals not conected to the main shaft axial canal, but somehow added later, just like the axial canals in the rosette formation of geodiid sterrasters ( Cárdenas & Rapp 2013). Then, they could be filled in some cases and be invisible in our observations. To conclude, we raise doubts as to the polyaxial nature of these spicules and warrant more observations at the interface between the tip of the tylostyles and their siliceous additions (spines and bulges).

There are currently five known species of Discorhabdella from the Pacific coast of Panama, Western Mediterranean, the Azores and New Zealand ( Table 1). Our new species differs from the other species by several characters: (1) presence of two types of pseudoastrose acanthostyles, one of which ( pseudoaster ) has entirely lost the shaft and is reduced to the inflated, spinose head, similar to an aster; (2) microscleres composed only of a single isochelae type, with sigma and oxydiscorhabd missing. The microsclere composition in Discorhabdella spp. is quite diverse, but only D. tuberosocapitatum ( Topsent, 1890) has only isochelae. The isochelae of the new species clearly differ from those of D. tuberosocapitatum , which is from Macaronesia (N-E Atlantic), by a different shape, with teeth nearly joining and the shaft bearing a lamella. This type of isochelae shape is unknown in the other species of the genus.

These isochelae, very unusual in Poecilosclerida , remind of the ‘palmate-anchorate-arcuate’ evolutionary sequence suggested by Maldonado & Uriz (1996) for aberrant chelae morphologies in Crambeidae genera Crambe and Discorhabdella . However, the isochelae of D. pseudaster n. sp., although possibly included in such a sequence, appear unique in Crambeidae , and more generally in Poecilosclerida . The most original character is the presence of a lamella on the shaft, a character rarely observed in isochelae. To our knowledge, this character is known only in the small isochelae of Hymenancora sirventi ( Topsent, 1927) in Myxillidae . An interesting other example could be one isochela found by Hinde & Holmes (1892, p. 200, Pl. IX, 39) in sediment from the Late Eocene, and tentatively attributed to Melonanchora elliptica Carter, 1874 . According to their description and drawing, this chela somewhat resembles those of the new species, although larger (66 µm) and bearing two lamellae instead of a single one. The presence of typical Discorhabdella spicules (tuberculate tylostyles and pseudoastrose acanthostyles) in these same Eocene sediments ( Hinde & Holmes 1892; Łukowiak 2015) suggests that this chela may belong to this genus.

The discovery of this 4 mm long new species emphasizes the need to carefully examine minute, inconspicuous, incrusting sponges on such rocky bathyal substrates, which certainly represent an underestimated source of biodiversity.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.