The Rise of Terroir in Champagne: Two Standout Producers In Search Of Precise Geography In Two Different Sub-regions (The Many Faces Of Meunier) + Recent Arrival: Clandestin ‘Elegant Champagne With A Burgundian Accent’

‘First and foremost, Champagne is wine.’

Our Champagne mantra over the past few years has been a bit reductionist: While undeniably accurate, it’s a little like saying that, first and foremost, ‘David’ is a hunk of marble or that at its essence, La Traviata is a bunch of notes. What these self-evident truths leave out is the human touch—the x-factor that makes art from the inanimate and beauty from the base.

As France warms with the rest of the planet, new regional wines are coming into focus and former sow’s ear soils are producing silk purse products. This is a paean to nature, of course, and as always, the passion arises from the people, not from the place. Folks like Alexandre and Fanny Heucq, fourth generation artisan winemakers from the grower house Champagne André Heucq and Olivier Langlais, the winemaker behind Solemme Champagne, who advocates simplicity and honesty in his wines.

These are two standout icons from our Champagne portfolio, but more than that, they are the flesh behind the finesse.

The Impact Of Climate Change on Champagne: Heating-up

Global wine production in 2023 was at its lowest in 60 years, and a lot of the decline can be blamed on extreme weather events, many of which have been worsened by climate change. Italy dropped from its position as the world’s leading wine maker due to numerous adverse weather events, including erratic rainfall that triggered downy mildew as well as floods, hailstorms and drought. In 2021—for the same reasons—Champagne saw the smallest harvest since 1957.

Somewhere amid all these clouds is a silver lining known as the Goldilocks Zone, and we may be living within it as we speak. Ripening grapes has always been a primary challenge in Champagne, located near the northern growing zone limit of its three principal grapes, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier. Although the rise in temperature (nearly two degrees between 1961 and 2020) has beneficial effects in the short term, especially at higher elevations, the downsides are legion—earlier budburst makes the risk of frost damage more pronounced, and frost control systems, especially those based on combustion, add to the region’s carbon footprint. Not only that, but warmer days often precede warmer nights, affecting a grape’s natural ability to retain acid, giving Champagne its intangible ‘zing’.

Despite magnanimous efforts to reduce their carbon emissions, including use of bio-based products in the fields and cellars, scrapping much of the mineral fertilizers used in the past and planting of hedges and trees allowing a better absorption of CO2 and storage of carbon in soils, the warming of the region is likely to continue for the foreseeable future—potentially, according to ClimateAi, making Chardonnay and Pinot Noir (and to a slightly lesser extent, Meunier) impossible to grow in the area currently defined as Champagne.

That means we may well be in the midst of a ‘best of both worlds’ phenomenon in Champagne, where the positives still outweigh the negatives and we are able to enjoy riper, richer wine that is today (more often than in the past) of vintage quality. By 2050, who knows?

The Biodynamic Principles: Respecting Earth’s Life Forces

Credit Dr. Rudolph Steiner for codifying the basic principles of biodynamics; his 1924 lecture series to farmers opened a wormhole that integrated scientific understanding with a recognition of an underlying spirit in nature and, indeed, in the cosmos at large. In Cliff’s Notes shorthand, the movement recognizes every farm, garden or vineyard as an integrated organism made up of interdependent elements: Plants, animals, soils, compost, and the classically French view of ‘the spirit of a place.’ Biodynamic farmers listen to the land and work to nurture and harmonize these elements, managing them in a holistic and dynamic way. The goal, whether the crop is grain or grapes, is to develop and evolve a given plot of land as a unique individuality.

These principles are custom made to accentuate terroir, but in Champagne, distinctiveness of location has often taken a back seat to a homogenous blend. As a result, the region as a whole was a bit late to the biodynamic party. The era between 1970 and 2000 may be viewed as cringe-worthy in terms of viticulture; the overuse of pesticides and herbicides and the once-favored fertilizer known as ‘boues de ville’—urban waste—damaged soils even in the most prestigious Grand Cru vineyards.

The biodynamic sun came out at turn of the century, when the Comité Champagne conducted in-depth research into the industry’s environmental impact and launched an ambitious plan, resulting in a 20% reduction in carbon emissions per bottle and a 50% reduction in the use of both phytosanitary products and nitrogen fertilizers. A regional sustainability certification, VDC (Viticulture Durable en Champagne), was introduced in 2014 and today, 15% of Champagne’s vineyards falls under the certification, and ambitions are much higher for the future.

The Mountain, And Then The Valley: The Many Faces Of Meunier

For the trend conscious (as well as the eco-conscious), Meunier, often the odd-grape-out in discussions of Champagne dominant trio of varietal, is enjoying something of a heyday with a growing legion of fans, both for its frost-resistance and its bright, bergamot-tinted profile. Of the planted acres in Champagne, Meunier represents about 31%, or roughly 84,000 acres. In the Marne Valley, however, it dominates, making up more than 60% of the vineyards.

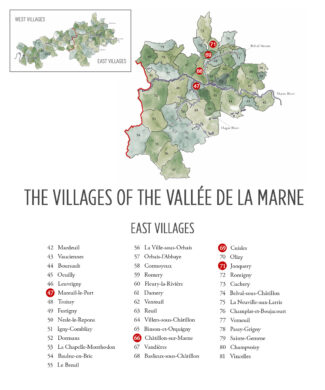

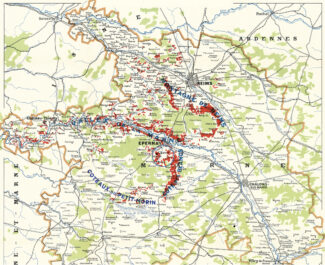

The valley is long—it extends more than sixty miles from the city of Tours-sur-Marne to Château-Thierry, wending thorough two départements, the Marne and the Aisne, all the way to the limits of Seine-et-Marne. As its name indicates, the Marne Valley follows the river through a landscape of rolling hills and small villages. Vines are planted on both banks although those on the north side benefit from a more favorable southern to eastern sun exposure.

The variety of Marne terroirs within its various villages and numerous sub-zones is expansive; in addition, the geology of the soils are more variable in Marne than in other Champagne sub-regions. As a result, the styles of Champagne, even those made mostly or entirely from Meunier, can vary widely. In the Petite Montagne, for example, the Meunier tends to be firmer and more structured, while the wines of the Vallée de la Marne are broader and more ample in build.

Representative of the many faces of Meunier are the artisan producers featured in this week’s selection, Alexandre and Fanny Heucq of Champagne André Heucq (whose mineral-focused Meunier is the result of their unique green Illite soils) and Olivier Langlais of Champagne Solemme, a vigneron who stands out from the pack as a true maverick, making Champagnes using only the year’s wines.

The Villages of The Vallée de la Marne: Coldest Weather in Champagne, Clay-Rich Soils

The most famous villages are located at the eastern end of the valley around the city of Épernay, a ranking that reflects the importance given to the presence of chalk in the soil. Chardonnay and Pinot Noir dominate the vineyards of the eastern end of the region, and the major Champagne houses located here include Billecart-Salmon or Philiponnat in Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, Deutz and Bollinger at Aÿ and Jacquesson in Dizy.

West of Châtillon-sur-Marne, chalk tends to be found more deeply buried in the ground; the topsoil is made of calcareous clay and clay marls. The combination of cold weather and rich clay makes Meunier the grape of choice in this part of the valley and it is here that a new generation of experimental winemakers is deepening their own (and by proxy) our understanding of the varietal.

Fanny & Alexandre Heucq

Champagne André Heucq

In the heart of the Marne valley is the tiny commune of Cuisles (population 150) which happens to be an epicenter for the green illite clay; it is unique to Cuisles and two surrounding villages and it is arguably the terroir where Meunier feels most at home.

According to André Heucq, who—along with his daughter Fanny— specializes in Meunier grown on fifteen acres of estate vineyards, “Green clay retains water better than chalky soils, this type of soil needs less water than classic clay-limestone soils. Generally speaking, the Marne Valley is prone to downpours of rain, and this is where Cuisles’ unique position in the hollow of the valley plays a fundamental role: Showers are much less frequent, so soil and climate are in perfect alchemy for optimum ripening of the Meunier.”

André & Fanny Heucq, Champagne André Heucq

Fanny says that the terroir, so vital to their wines’ purity and elegance, is enhanced by a commitment to biodynamics: “Production that respects the environment reactivates the vine’s natural self-defense mechanisms, allowing us to do away with the use of chemicals and use very low doses of copper and sulfur.”

Among the strictest (and most interesting) of the cosmos-oriented techniques the estate relies on is the ‘500’—a preparation is obtained by fermenting good quality cow manure in the soil over the winter, introduced via cow horns. Fanny explains, “This preparation is aimed at the soil and plant roots. Its name comes from the fact that it contains over 500 million bacteria per gram. The silica from the horn is equally important. It is complementary to and acts in polarity with the 500. It is not aimed at the soil, but at the aerial part of plants during their vegetative period. It can be said to be a kind of ‘light spray’, which can promote vegetative vigor or, on the contrary, attenuate excessive luxuriance. It brings a luminous (crystalline) quality to plants, and reduces their tendency to disease. Not only does it reinforce the effects of sunlight, it also enables a better relationship with the cosmic periphery, with the entire cosmos. This preparation is essential for the internal structuring and development of plants. It promotes vertical plant growth. It makes plants firmer and more supple. It increases the quality and resistance of leaf and fruit epidermis.”

Views From The Right Bank: Meunier Reigns Supreme

Not only an underdog but occasionally an afterthought, growers in Champagne have often planted Meunier vines in areas that will not support the appellation’s noble couple, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Older vines are often found in otherwise marginalized areas, and the grape is not permitted to wear the designation ‘Grand Cru’ even if it is grown exclusively in a Grand Cru village. As a logical result of this elitism, very little Meunier is grown in Grand Cru vineyards and many producers avoid using it in their vintage wines due to its rumored inability to age—a rumor which, incidentally, is unfounded.

As in Bordeaux, the difference between the right and left banks of the region’s dominant river are striking, both in terms of vineyard exposure and soil composition. The Marne is an eastern tributary of the Seine in an area east and southeast of Paris. In Champagne, where it runs west toward Épernay, the right bank sports the valued south/southeast exposure that maximizes sun exposure and aids grape ripening. As with the Right Bank of the Dordogne River in Bordeaux, the Marne’s right bank contains more clay, making it more suited to Meunier than either Chardonnay or Pinot Noir, which may struggle to ripen in the area’s cool, frost-and-fog-prone microclimate.

Champagne André Heucq ‘Héritage’ Blanc de Meunier, Vallée-de-la-Marne Brut Nature ($51)

Champagne André Heucq ‘Héritage’ Blanc de Meunier, Vallée-de-la-Marne Brut Nature ($51)

100% Meunier harvested in 2016/2017 from 30-year-old vines grown in illite-rich plots in Cuisles, Châtillon-sur-Marne, Serzy and Mareuil-le-Port. The wine underwent full malo and spent 48 months on lees; it was dosed to Brut Nature. The nose is nicely spiced with stewed apple and pear with notes of jasmine. A slight lemony bitterness on the finish is a mirror of the terroir. 25,000 bottles made.

Champagne André Heucq ‘Hommage Parcellaire’, 2015 Vallée-de-la-Marne – Jonquery ‘Les Roches’ Brut Nature ($117)

Champagne André Heucq ‘Hommage Parcellaire’, 2015 Vallée-de-la-Marne – Jonquery ‘Les Roches’ Brut Nature ($117)

100% Meunier from younger vines—22 years old—grown in illite in the ‘Les Roches’ lieu-dit in Jonquery. The wine is from the 2015 harvest, fermented ‘en barrique’ and aged three years on lees after undergoing full malo. Dosed to Brut Nature. The wine’s bouquet is of peach and plum with notes of pie crust and almond. The long and pronounced minerality in the finish is indeed an earthy homage to the parcel from which it arises. Only 800 bottles were made.

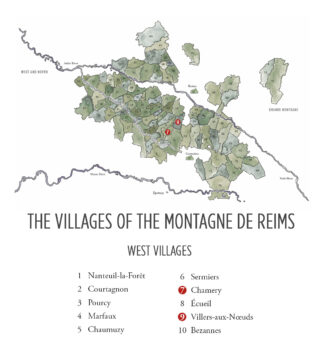

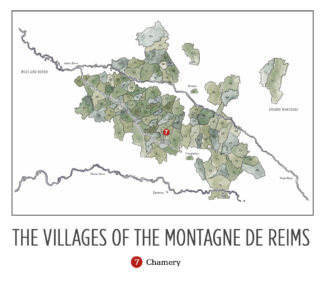

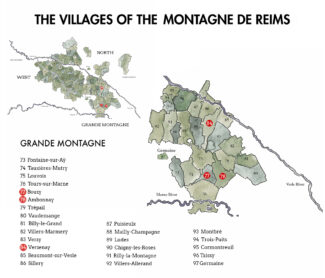

The Montagne de Reims: Grande, Petite, North And The Grand Vallée

Located between Reims and Épernay, the Montagne de Reims is a relatively low-lying (under a thousand feet in elevation) plateau, mostly draped in thick forest. Vines find a suitable home on the flanks, forming a horseshoe that opens to the west.

So varied are the soils, topography and microclimates here that it is not possible to speak of the region in any unified sense. Grande Montagne de Reims, which contains all of the region’s Grand Cru vineyards, covers the northern, eastern and southern slopes of the viticultural area, and Pinot Noir plantings dominate at 57%, followed by Chardonnay (30%) and Meunier (13%). Its vineyards face a multitude of directions, and soil type varies by village, giving rise to a breadth of Pinot Noir expressions, as well as exceptional Chardonnay.

To the west, the Grande Montagne de Reims gives way to the Petite, whose bedrock is chalk, but softer than the chalk found further south on the Côte des Blancs. This sort, called ‘tuffeau’, is an extremely porous, sand-rich, calcium carbonate rock similar to what is found in wine regions of the middle Loire Valley.

In French, the word ‘petite’ often to refers to a ‘lesser’ commodity, but with La Petite Montagne, the reference is to elevation. This lower elevation means warmer weather, even in Champagne’s northerly climate, and in certain villages, the soil contains more sand, making it an ideal environment for growing Meunier.

Meunier accounts for approximately half of the plantings in the Petite Montagne, with Pinot Noir making up 35% and the rest Chardonnay. It is a growing conviction among growers of the modern era that Meunier is a Champagne grape whose time has come, especially as an age-worthy variety.

Emmanuel Brochet of Villers-aux-Nœuds says, “People claim that Meunier ages too quickly, even faster than Chardonnay. I disagree. The curve of evolution is different. Meunier is quick to open and more approachable in youth, but then it becomes quite stable. Chardonnay tends to open later, but old Meunier remains very fresh and lively.”

Olivier Langlais

Champagne Solemme

The name Solemme is a combination of ‘sol’ for the sun, with the addition of a feminine suffix. “My goal,” says cellar master Olivier Langlais, “is to make delicate Champagnes that are bright like the sun.”

La Petite Montagne-de-Reims, to the west of the road between Reims and Épernay, boasts steep slopes and chalky soils, making it the home of some of the best vineyards in Champagne—Savart, Brochet, Egly-Ouriet, etc. Also calling the region home is Olivier Langlais, who farms fifteen acres of organic vineyards in the terroir around Villers-Aux-Nœuds. A true exception in Champagne region, he makes wines using only the product of the harvest year.

His dedication to biodynamics and agriculture according to the cycles of the moon began with the Chardonnay plot in 2009 and finished the transition with his oldest vines of Pinot Noir in 2015. The vineyard is composed of 50% Meunier, 25% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir divided between six villages—five of them Premier Cru. Most of the plots, as is the case of most Petite Montagne de Reims vines, are southeast/east oriented.

Olivier Langlais, Champagne Solemme

“Everything is happening in the exchange between the soil and the grape,” Olivier points out. “That’s why the difference of terroir between all parcels determines variety and process. Villers-aux-Nœuds has a classic chalky soil, bringing a lot of minerality to the Chardonnay and Meunier growing there. Clay-limestone dominates Chamery and Vrigny, with a bit more clay in Vrigny, where Meunier gets better results—clay gives more ‘gras’, or roundness to the grapes. Often not mentioned is the sandy soils of Villedomange and Éceuil, which gives Pinot Noir a concentrated and elegant form.”

Once in the cellar, Olivier is a champion of a hands-off approach. He never chaptalizes and uses only natural yeast from his vineyard. “In the chai, you won’t find any barrels,” he says. “We do not filter, there is no addition of SO2 and all the cuvées spend between 36 to 48 months on the lees as a means of better expressing the terroir. 90% of the time, I don’t do any malolactic fermentation, because I prefer to let the natural minerality shine.”

Varietal Transformation in The Petite Montagne: Meunier Shares Space With Pinot Noir

The western portion of the Montagne de Reim—the so-called Petite Montagne—stretches from Gueux in the north to Sermiers in the south, on the western side of the main road that runs between Épernay and Reims. Although this region has a historical fondness for Meunier, some acres have been replanted to Pinot Noir in recent years, potentially doing a disservice to the vineyards north of Écueil in the villages of Sacy, Villedomange, Jouy-lès-Reims, Coulommes-la-Montagne, Vrigny and Gueux. But the soils here are generally more overtly calcareous than those in the Vallée de la Marne and can contain a high proportion of fossils. In Écueil, there is sand on the lower slopes, acting as a defense against phylloxera, allowing some growers to plant Pinot Noir on the original rootstocks, so this becomes the cultivar of choice.

Champagne Solemme ‘Terre de Solemme’, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds Brut ($59)

Champagne Solemme ‘Terre de Solemme’, Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds Brut ($59)

Villers-aux-Nœuds is a Premier Cru village in Vesle et Ardre; about half the vineyards are planted to Pinot Noir, with Meunier making up about 30%, and the rest, Chardonnay. Olivier Langlais farms fifteen acres here; the land is relentless hilly and the soil is made up of Cretaceous chalk under a few inches of ‘argilo-calcaire’ topsoil. Disgorged according to the moon cycle (a feature of his brand of biodynamics), ‘Terre Solemme’ is a blend of 55% Meunier, 25% Pinot Noir, and 20% Chardonnay aged three years on the lees. Buttery toast on the nose along with cooked apple and cantaloupe. The palate has an echo of the nose and a nice marzipan richness that drives the mineral finish home.

Champagne Solemme ‘Ambre de Solemme’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds ‘La Motelle’ Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature ($99)

Champagne Solemme ‘Ambre de Solemme’, 2016 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Villers-aux-Nœuds ‘La Motelle’ Blanc de Noirs Brut Nature ($99)

100% Meunier from the ‘La Motelle’ lieu-dit, filled with 50-year-old Massal-selected vines; these grapes were harvested somewhat late and developed a spectacular ripeness. ‘Ambre’ refers to the color, whose slight tint is the result of skin-contact. The nose sets out with fresh apple and a touch of grapefruit and strawberry coming out, with bold acidity reflected in a spine of salinity that balances an otherwise rich and creamy wine.

Champagne Solemme ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Brut Nature ($79)

Champagne Solemme ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Brut Nature ($79)

2018 was an excellent vintage in Champagne; the crop was large and healthy, rich in sugar and flavor depth, with all three major grape varieties performing well. ‘Esprit de Solemme’, 2018, is equal parts Meunier and Chardonnay drawn from chalky soil in Villers-aux-Nœuds and the clay-limestone hillsides of Chamery. This cuvée shows a lovely bouquet: cream, biscuits, pineapple and toasted nuts. The palate is very dry but stays in balance with cream and salinity through the finish.

RECENT ARRIVAL

The wine world is a churning urn of burning trends, and what catches fire in America is not necessarily the same thing that ignites Europe: The concept of ‘grower Champagne’, for example, often carries more weight here than it does among the Champenois producers themselves. Champagne made in-house from grapes grown on the estate may wear the grower Champagne label, while the majority of Champagne houses purchase grapes as négociants and create signature blends. When a house wears ‘Domaine’ on the label, it is the former; ‘Maison’ generally represents the latter.

Between the two is the micro-négociant, who operates on a smaller scale and often produces high-quality micro-cuvées, controlling production from vineyard to bottling, and focuses on representing individual vineyard sites.

One micro-négociant estate that is capturing attention of both here and in Aube is Champagne Clandestin, a joint venture between Meursault-trained winemaker Benoît Doussot and Aube legend Bertrand Gautherot of Vouette & Sorbée.

Micro-Négociant

Champagne Clandestin

‘Elegant Champagne with a Burgundian Accent’

‘Clandestin’ means exactly what you think it does—something hidden, something to be explored. In this case, it refers to the Aube’s long-overlooked, west-facing parcels of Pinot Noir on Kimmeridgian soils as well as Chardonnay on Portlandian soils above Buxières.

These cuvées represent vineyards that have generally been eschewed in the region; southerly, easterly and southeastern-facing parcels have long been favored in the Aube because they are exposed to more sunlight during day while their western counterparts have never been fully utilized. Both Bertrand and Benoît were convinced that a longer and slower ripening and maturation process could imbue the wines with added complexity and depth. Clandestin is made from 20 acres of cooler, west-facing vineyards, which are farmed organically, certified by ECOCERT and vinified according to the exacting standards for which Vouette & Sorbée is known.

Benoît says, “After pressing, the wine is aged in French oak barrels following closely the training I received in Meursault before moving north to Champagne. This wine should appeal to purists in search of minerality, cut, and precision. Because we insist on harvesting perfectly ripe grapes, which is not generally the case in Champagne, the wines can be bottled with no dosage, giving room for the oceanic terroir to really shine through.”

nv Champagne Clan Destin ‘BORÉAL’ Côte-des-Bar Brut Nature ($79)

nv Champagne Clan Destin ‘BORÉAL’ Côte-des-Bar Brut Nature ($79)

Harvest 2020. 100% Pinot Noir grown on vines between 20-35 years old, fermented and aged in French oak before aging sur latte for 15 months before being disgorged with zero dosage. Earthy aromas of wild strawberries, brioche and toast waft from the flute followed by a delicate mineral crunch. Disgorged July 2022.

Notebook ….

Single Harvest vs. Vintage

In France, under Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) rules, vintage Champagnes must be aged for three years—more than twice the required aging time for NV Champagne. The additional years on the yeast is said to add complexity and texture to the finished wine, and the price commanded by Vintage Champagne may in part be accounted for by the cellar space the wine takes up while aging.

On the other hand, a Champagne maker might prefer to release wine from a single vintage without the aging requirement; the freshness inherent in non-vintage Champagnes is one of its effervescent highlights. In this case, the wine label may announce the year, but the Champagne itself is referred to as ‘Single Harvest’ rather than ‘Vintage’.

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

To be Champagne is to be an aristocrat. Your origins may be humble and your feet may be in the dirt; your hands are scarred from pruning and your back aches from moving barrels. But your head is always in the stars.

As such, the struggle to preserve its identity has been at the heart of Champagne’s self-confidence. Although the Champagne controlled designation of origin (AOC) wasn’t recognized until 1936, defense of the designation by its producers goes back much further. Since the first bubble burst in the first glass of sparkling wine in Hautvillers Abbey, producers in Champagne have maintained that their terroirs are unique to the region and any other wine that bears the name is a pretender to their effervescent throne.

The INAO defines the concept like this: “An AOP area is born of an alliance between the natural environment and human ingenuity. From that alliance comes an AOP product with unique, inimitable characteristics, a product so different that it complements rather than competes with other products, possessing a particular identity that adds further value.”

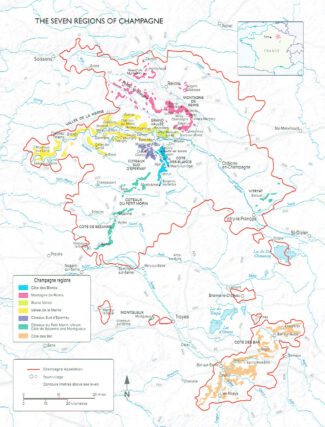

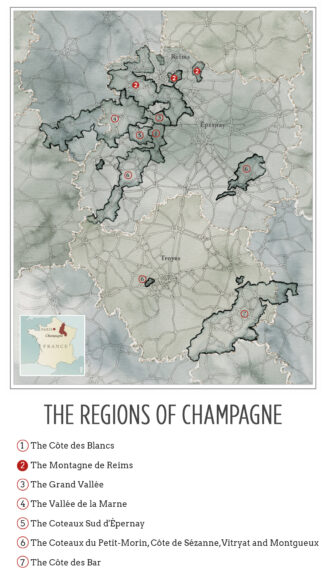

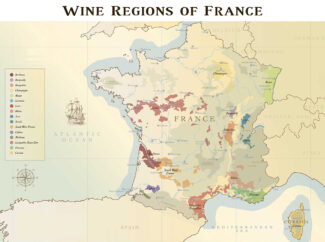

In 1927, the viticultural boundaries of Champagne were legally defined and split into five wine-producing districts: The Aube, Côte des Blancs, Côte de Sézanne, Montagne de Reims, and Vallée de la Marne. The CIVC (Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne), formed in 1941, decreed that everyone who wanted to plant vines and grow grapes to be used in the creation of Champagne had to be registered, and if you didn’t register back then, there is no out, even now. Originally, grape growing was not a profitable business and was an afterthought meant to utilize chalky slopes where grain would not grow. As a result, many farmers at that time did not register, and today, a tour along the Route Touristique de Champagne, you’ll come across unregistered fields that lie fallow between two registered vineyards.

… Yet another reason why this tiny slice of northern France, a mere 132 square miles, remains both elite and precious.

- - -

Posted on 2024.01.14 in France, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

A Window To The Past: Burgundy’s Strongest Statement is Fully In Evidence In Ten-Year-Old Gevrey-Chambertin Seventeen 2014 Wines Show Depth And Breed. (4-Bottle Village-Pack $379) + (3-Bottle Premier Cru-Pack $379)

A Gevrey New Year from us to you! In a time of reflection and introspection, we’re also suggesting a bit of ‘retrospection’—a deep dive into the marvelously mature 2014s from the Burgundian appellation most celebrated for its longevity. This curated selection is a window into the art of evolution as it applies to Gevrey-Chambertin Pinot Noir held in ideal conditions for the past decade. From some of the finest producers in Gevrey, these are wines which emerge from their chrysalis of cellaring to display the nuanced emotion, complexity, refinement and texture that only patience can reveal.

Consider this a celebration of the moment when you truly recognize that a wine’s aroma has become its bouquet.

What Makes A Wine Great?

Superlative winemaking involves a formula that’s part science and part soul. It’s not a stretch to liken the process to a recipe, and so a comparison of a great wine and the steps required to produce a perfectly prepared, top-end Wagyu ribeye steak may be apropos. Like wine, an exceptional piece of beef must trace its origins to the earth itself: Wagyu cattle are pampered from birth, fed a high-protein diet, often massaged and given beer to encourage marbling. Likewise, the vineyards that produce top quality wines enjoy both breeding and babying; adding to the natural elements is a cycle of biodynamics to mollycoddle microbic life, with the correct attention paid to moisture, food and pruning. While in the growth stage, all possible care is taken so that the vines do not fall prey to disease or mismanagement.

And the same holds true for the steer.

Once harvested, both products are handled with extra care, but in the cellar—as in the kitchen—the skill of the creator is paramount. A misstep along the way may result in a whole lot of wasted effort earlier in the game.

Of course, for both beef and bottle, the consumer is the ultimate benefactor and the decisive judge; the time the wine spends maturing toward an ‘ideal’ state is the time the steak spends over the flame. This is, of course, an optimal and somewhat measurable period depending on individual tastes, but a given consensus can certainly be formed and debated.

And this is precisely the key factor separating great wine (and great cuisine) from the also-rans, just as it is true that the broader the consensus, the pricier the product tends to become.

The esoterica we consider when we call a wine ‘great’ are nuance and identity. The former is formed purely through organoleptic sensations, the latter via reputation and history—how well the wine represents and reflects its place of origin. The status of ‘great’ must always be opinion, but at the same time, the more you know and the deeper you look, the more credible your opinion becomes.

So, to ring in 2024, let’s raid the cellar and fire up the grill and put these theories to the ultimate test!

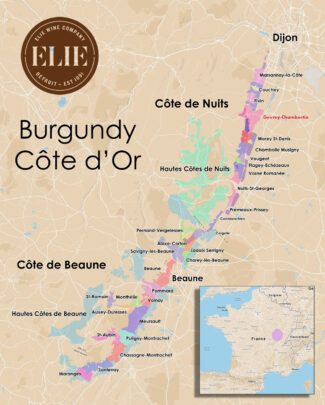

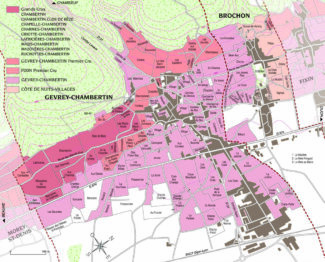

Gevrey-Chambertin: Setting The Boundaries

“The Emperor will drink only Chambertin,” said Louis Constant Wairy, Napoleon’s valet.

Indeed. So what does Gevrey-Chambertin have in common with Westland, Michigan? Not much, except that Westland was named for a mall and Gevrey-Chambertin is named for a vineyard. As those schooled in Burgundian lore know, during the nineteenth century it became fashionable for villages in the Côte d’Or to adopt double-barreled names, adding a hyphen followed by the name of their most famous vineyard: Thus Chambolle added Musigny and Gevrey added Chambertin.

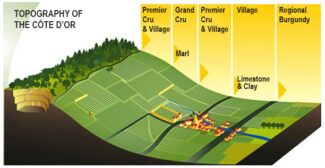

In minimalism, less may be more, and in wine—especially those with a hyphenated name—more may be less; a village-level Gevrey-Chambertin, for example, does not seek to compete with the quality of ‘Le Chambertin’ itself. But if nothing else, its name reminds you that it comes from a rarefied zip code. And to be sure, the region is hallowed grapeland, graced with the Holy Trinity of terroir—elevation, climate and soil structure. Contained within the appellation are nine Grand Crus and 26 Premier Crus (whose name on the label may be followed by the name of the climat of origin) as well as nearly a thousand acres of Villages wine.

The 2014 Vintage: Ten Years Of Age Matures Into A Classic

If you follow this sort of thing, you know that in Burgundy, Vintage 2015 was a media-magnet, extraordinary throughout the Côte d’Or. A mild, wet winter replenished water reserves sorely needed during a hot, dry summer. A few inches of rain in June, followed by a further inch or so in August—critical to refresh the vineyards and ensure even ripening, but not so much as to mask the region’s diverse terroir in sweet fruit.

All this 5/5 scoring talk is fine, but it should not serve as temptation for any true Burgundy lover to overlook 2014.

A more difficult vintage by all accounts, the summer of 2014 was wet and chilly interspersed with a few hot days in July and worsening weather during the first half of August. There was surprisingly little mildew, but maturation proceeded slowly. And then, things took a turn for the better: The skies cleared, the mercury rose, and victory was seized from the jaws of disease, decimated yields and vinegar flies.

Especially in the Côte de Nuits, the final verdict is just becoming obvious. The wines, though less voluptuous and rich than 2009 or 2012, but also riper than 2008 (which had a similar growing season) have proven to be classic. Ten years later, the proof is in the goblet; these wines, pure and limpid at bottling, have matured admirably and are of a weight and concentration that indicates near peak performance.

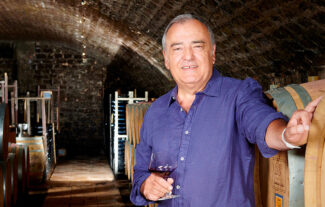

Domaine Dominique Gallois

Prior to taking over the family estate in 1989, Dominique Gallois studied catering in Paris and ran his own restaurant for six years. When he returned to Burgundy, the domain consisted of six acres in Gevrey-Chambertin which his father had managed for forty years, selling the grapes to négociants. Dominique began to renovate the property and in 1989 (after purchasing additional acreage in Combe aux Moines, Petits Cazetiers and Goulots) to bottle his own product, looking first to private customers to build a reputation.

Dominique Gallois, Domaine Dominique Gallois

Recognizing that he works in terroir that is the envy of the world, Dominique takes special care to work the domain by hand, without pesticides or herbicides. Says Gallois, “Our year is quite full; winter months are dedicated to vine maintenance and Guyot-style pruning. During spring and summer, several tasks are performed allowing yields to be controlled and managing the healthiness of the future grapes. Harvesting is manual—we count on a small, faithful team to carry out the first sorting on the vine. Thereafter, grapes pass over a sorting table where bunches are inspected so as to conserve only the best fruit.”

Bottle 1 • Village Pack

Bottle 1 • Village Pack

Domaine Dominique Gallois, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ($95)

In Burgundy, any serious discussion of terroir begins at the Village level, and the most important of these appellations are aligned in a neat north-to-south line from Marsannay to Maranges. They generally located on a commune’s eastern side, where the angle of slope is slight, or along the far western fringe, adjacent to forest-capped ridgelines, where both elevation and slope are far more significant. Not all are created equal, of course, and it can be expected that the concentration of Gallois’ Gevrey, blended from numerous climats and celebrating its tenth anniversary, is at its finest. The nose shows deep cherry spice, licorice, and earth, with perfectly integrated oak and fruit leather, the palate cinnamon and black pepper and a finish that remains both rugged and refined.

Bottle 1 • Premier Cru Pack

Bottle 1 • Premier Cru Pack

Domaine Dominique Gallois, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Petits Cazetiers ($120)

Les Petits Cazetiers is a tiny Premier Cru climat just west of the village of Gevrey-Chambertin; the enclave is walled and planted entirely to Pinot Noir, covering barely two acres. In fact, Gallois is the only producer making a wine under the Les Petits Cazetiers Premier Cru name. From the well-drained limestone and marl comes a wine rich in earth tones, most notably mushroom, which has evolved into tertiary notes of nuts, spice and dried cherry.

Domaine Dominique Gallois, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru La Combe aux Moines ($150)

Domaine Dominique Gallois, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru La Combe aux Moines ($150)

At 1300 feet, Combe aux Moines is among most elevated in Burgundy, and the wines are both rarefied and rustic, exhibiting bright red fruit alongside earthy characters. The 12-acre climat sits at Gevrey’s northern end, quite a distance from the contiguous Grand Cru hill. Instead, Combe aux Moines is bounded by other east-facing Premier Cru climats like Les Cazetiers and Champeaux. It angles slightly north, meaning that the vines have less exposure to the sunshine than the south-facing vineyards that lie just outside the village; however, the steep slope ensures that the morning sunlight is distributed efficiently. Soils are free draining and fairly infertile, lessening the vigor of the vines and leading to the production of small, concentrated grapes often been linked to the muscularity of the finished wines. This one retains a solid core of red fruit behind the savory scents of tobacco and forest floor.

Domaine Domonique Gallois, 2014 Charmes-Chambertin Grand Cru ($390)

Domaine Domonique Gallois, 2014 Charmes-Chambertin Grand Cru ($390)

One of the lesser known Grand Cru sites in Gevrey, Charmes occupies the lowest and most shallow slopes of the Grand Cru belt close to the border with Morey-Saint-Denis. It consists of a number of blocks divided by minor roads or walls and in general, produces softer, less muscular wines than many of its neighboring Grand Crus, including Chambertin itself. As such, the longevity is not as pronounced, and in consequence, tends to mature more quickly. It remains a varsity-level Burgundy, however, with a deeply structured core, showing the cherry, bilberry of its youth along with the mineral and spice of adulthood, then happily builds to a stone and spice finish that displays equilibrium and finesse.

Domaine des Tilleuls

Damien Livéra, whose Italian great-grandfather founded the domain in 1920, decided on a different approach when he took the reins in 2007. Formerly a wine made from négociant-purchased fruit (mostly Bouchard Père and Louis Jadot) Damien decided to go maverick. First he improved the Tilleuls’ ‘cuverie’—wine storehouse—and expanded the amount of wine drawn from the domain’s 21 acres that was bottled in house. This vineyard land includes plots of Bourgogne, Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, Fixin, and Gevrey-Chambertin, the Crus En Champs, Évocelles and Clos Village as well as a plot of Chapelle-Chambertin in the sub-climat Gémaux.

Damien Livéra and Family, Domaine des Tilleuls

Damien also made a push to see the family’s vines cared for with a more earth-friendly and quality-focused attitude, pushing for lower yields and healthier, more balanced fruit. Vineyards are cared for sustainably, which includes plowing the soils (no herbicides) and using indigenous yeasts in the cellar. A majority of the estate’s older Pinot Noir vines were planted in the 1950s and 1960s. Grapes are harvested by hand and mostly destemmed, fermented in tank and then aged in French oak barrels in very cold cellars—so cold that malolactic fermentations may extend over a full year. The family uses from 25% new oak on base wines to 40 percent on Villages-level wines and between 50 to 100% for Grand Crus. Selections are bottled unfined and unfiltered.

Bottle 2 • Village Pack

Bottle 2 • Village Pack

Domaine des Tilleuls, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ‘Clos Village’ ($94)

This is the Livéra family’s flagship wine; they own four acres of the Gevrey-Chambertin wall-enclosed Clos Village and make the wine with the intention that it be cellared: Vinified in 40% new oak for 12 months and then 6 months in stainless-steel vats, with neither fining nor filtration. Damien Livéra recommends waiting a minimum of 5 years before opening; ten if circumstances allow. A complex and structured wine in the full bloom of earthy elegance.

Domaine des Tilleuls, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ‘Les Évocelles’ ($94)

Domaine des Tilleuls, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ‘Les Évocelles’ ($94)

Évocelles is a 25-acre upper-hillside vineyard, sharply inclined and full of stones. It is located at the very north-east portion of Gevrey, principally in Brochon, bordering the Premier Cru of Champeaux and Les Goulots. The primary geology of this Village-level lieu-dit is clay-limestone and the vines were planted in 1950. The palate remains medium-bodied with still-supple tannins and a fine bead of acidity—quite an elegant Les Évocelles with a lightly spiced finish.

Domaine des Tilleuls, 2014 Chapelle-Chambertin Grand Cru ($350)

Domaine des Tilleuls, 2014 Chapelle-Chambertin Grand Cru ($350)

One of the area’s lesser-known sites in the Grand Cru belt, Chapelle is located immediately below the commune’s more prestigious climat, Chambertin Clos-de-Bèze. It covers 13.5 acres of limestone-rich soil whose stony texture allows for free drainage and forces the vines to grow deep, strong root systems in search of water. In ideal seasons, warm days and cool nights help the grapes maintain a balance between natural sugars and acidity, which echo in the finished wines. In the 2014 vintage, the terroir has emerged from behind overt vintage character and is now clearly on display, having mellowed into appealing and exotic aromatics.

Thibault Liger-Belair

Winemaking has been the legacy of Liger-Belair family for a quarter of a millennium. Prior to establishing his own domain, Domaine Thibault Liger-Belair studied oenology, worked for a communications firm in Paris and started an internet company to discover and sell high quality wines. Still, the vines beckoned, and in 2001, at the age of 26, he returned to them. The following year saw his first harvest of Nuits-Saint-Georges, and in 2003, he expanded into Richebourg Grand Cru, Clos Vougeot Grand Cru and Vosne-Romanée Premier Cru Petits Monts and in 2004, he discovered biodynamics, a train on which he has been a front-row passenger ever since.

Thibault Liger-Belair

“I saw a change in my vineyard, which went from grey soils to brown/red and then sometimes to black.” Still, his overarching philosophy is that each vineyard needs something different: “I don’t like 100% of anything: new barrels, whole clusters. My job is to decide which grapes we have and then decide a viticulture and winemaking approach.”

In 2018, he made wine from 23 different appellations and purchased grapes from a ten more, but did the work there. “We don’t purchase grapes where we don’t do the work,” he says.

Bottle 3 • Village Pack

Bottle 3 • Village Pack

Thibault Liger-Belair, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ‘La Croix des Champs’ ($99)

Liger-Belair’s scant 1-acre parcel of 40-year-old vines is grown in the fairly rich soils of La Croix des Champs lieu-dit on the far side of the Route Nationale. The wine remains expansive with a solid and, complex mineral layer, well integrated oak and fine-grained tannins behind notes of tarragon, cedar and chocolate.

Thibault Liger-Belair, 2014 Charmes-Chambertin ‘Aux Charmes’ Grand Cru ($370)

Thibault Liger-Belair, 2014 Charmes-Chambertin ‘Aux Charmes’ Grand Cru ($370)

‘Aux Charmes’ borders the Grand Cru Chambertin; it is east-facing with iron-rich soils and vines between 80 and 100 years old. Thibault Liger-Belair’s parcel was planted in 1946, three-quarters of an acre located at the top of the vineyard, just below the border between Chambertin and Latricières. The ‘greenness’ of the scent remains intact as an integral part of this wine’s beauty, with touches of herbal tea and underbrush.

Domaine Heresztyn-Mazzini

Florence and Simon Heresztyn-Mazzini hail from different winemaking regions—Florence from Burgundy and Simon from Champagne. After ten years of working Heresztyn-owned vineyards in Gevrey-Chambertin, the couple decided to start their own venture on 14 acres spread across the villages of Gevrey-Chambertin, Morey-Saint-Denis, and Chambolle-Musigny. 2012 was their first vintage.

Florence and Simon Heresztyn-Mazzini, Domaine Heresztyn-Mazzini

“Here in Gevrey-Chambertin,” Simon says, “we have had only this one objective since 2012: to work according to organic and biodynamic practices in the vineyard, vat-house, and cellar and to offer Grand Cru, Premier Crus and Village wines that are closest to the identity of their climats. Our vineyards were certified organic in 2014 and we have been farming biodynamically in 2015.”

Florence adds, “We are closely attached to the Côte de Nuits and its unique terroirs and work relentless to bring out the region’s best qualities. Simon and I make it a point of personal pride to respect the region’s soils and natural environment.”

Bottle 4 • Village Pack

Bottle 4 • Village Pack

Domaine Heresztyn Mazzini ‘Vieilles Vignes’, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ($91)

Pinot Noir made from 50 year-old vines and aged in Allier and Tronçais barrels for 18 months; it holds onto a great portion of its dark fruits and tannic spine. An exceptionally well-made Village wine that has received better reviews than several Premier Cru Gevreys from the 2014 vintage.

2014 Domaine Heresztyn Mazzini ‘Vieilles Vignes’ Gevrey-Chambertin ‘Les Songes’ ($91)

2014 Domaine Heresztyn Mazzini ‘Vieilles Vignes’ Gevrey-Chambertin ‘Les Songes’ ($91)

Les Songes is smaller than an acre of clay/limestone peppered with marl-rich fossilized shells. The wine was 35% whole-bunch fermented on wild yeast fermentation and aged in 30% new wood oak barrels for 16-18 months. The wine retains plenty of energy and a plumpish body; the tannins are mellow and silky while the acidity has reined in to show cool minerality and edge.

Bottle 2 • Premier Cru Pack

Bottle 2 • Premier Cru Pack

Domaine Heresztyn-Mazzini, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Champonnets ($120)

Champonnets is a Premier Cru climat just south of Gevrey-Chambertin on the northern edge of the Grand Cru hillside. Wines from this 8-acre vineyard tend to be less robust than others from the area, displaying silkier tannins, due in part to the northeasterly aspect where the cold winds that flow through the Combe de Lavaux gives Champonnets a cooler mesoclimate than the more sheltered Grand Cru sites that face southeast on the other side of the hill. While vines still have sufficient sunlight during the growing season to develop good sugars and acidity, the grapes lack the concentration of warmer, sunnier climats. Still, the high proportions of limestone is well-suited to the Pinot Noir that grows here, storing sufficient water for hydration while also providing plentiful drainage. The wine shows dried fruit and warm leather on the bouquet along with a slightly smoky palate and a chamois texture from the tannins.

Domaine Heresztyn-Mazzini, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru La Perrière ($120)

Domaine Heresztyn-Mazzini, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru La Perrière ($120)

La Perrière runs adjacent to the Mazis-Chambertin Grand Cru, separated only by a dirt path. The vineyard’s name refers to its former occupation as a quarry, and as might be expected, there is a pronounced minerality to wines that bear this designation. Soil from the surrounding area was used to fill in the quarry and this light, loamy topsoil is underscored by free-draining calcareous stones. This elegant and solid-state wine could easy withstand another half-decade in the cellar, but for now it shows perfume of wood, and sous bois with a mineral-inflected finish shaped by impressively fine-grained tannins.

Domaine Odoul-Coquard

Sébastien Odoul—whose name should never be associated with that non-alcohol beer from Anheuser Busch (!) cut his winemaking teeth at Domaine Dujac, Mommessin, and Domaine Denis Mortet. In 2004, he returned to the family domain to join his parents, Sylvette and Thierry, and as of 2009, he took over the estate as vigneron.

In all, the family farms 25 acres in 21 different appellations throughout the Côte de Nuits; most notably, they own the majority of the lieu-dit vineyard of Les Crais Gillon in Morey-Saint-Denis. All of their farming is done with ‘lutte raisonnée’, a sustainable viticulture practice.

Sébastien Odoul, Domaine Odoul-Coquard

Discussing his different properties, Odoul says, “Morey-Saint-Denis is about fruit and finesse. Not as much finesse as Chambolle-Musigny though. The tannins are more supple than in Gevrey-Chambertin. Basically one could say that Morey-Saint-Denis is like a blend of Chambolle and Gevrey. When it comes to the fruit it is more Chambolle in character, while the tannins are more well-integrated, as in Gevrey.”

After bottling, Odoul gives a third of the result to the commune, explaining, “We have had this arrangement since 1988. My father was the grower in the village with the least amount of Premier Cru vineyard, so they let him have the Clos la Riotte. Since we are not the owners we can’t say it’s a monopole. The commune sells its part with a different label.”

Bottle 3 • Premier Cru Pack

Bottle 3 • Premier Cru Pack

Domaine Odoul-Coquard, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin Premier Cru Aux Combottes ($140)

12-acre Aux Combottes is Gevrey-Chambertin’s southernmost Premier Cru climat, sitting on the border with Morey-Saint-Denis. The terroir is not quite as high-quality as the Grand Cru vineyards which surround it, but it is certainly one of Gevrey-Chambertin’s top Premier Cru sites. In fact, in the hands of top producers, Combottes can outperform other Premier Crus and some lesser Grand Crus—it’s primary (and perhaps only) drawback is that it lies in a slight depression that funnels cold westerly winds over the vines during the growing season, making complete ripening a challenge. This wine is drawn from three vine ages; according to Sébastien, they are “10, 25 and ‘very old.’” Having seen 75% new oak, wood spice remains to shore up the middle palate of dried strawberry and cedar, but has by now taken a back seat.

Domaine Bernard Dugat-Py

Dugat-Py flies a bit under the radar in Gevrey, possibly overshadow by or confused with Domaine Claude Dugat. Same family, different property.

Located at the base of the Combe de Lavau, Dugat-Py has been producing world-class wines since its founding. The aging cellar forms the focal point of the domain’s architecture; L’Aumôneri, is essentially a small abbey that was built by the Diocese of Dijon in the 11th century, making it the oldest cellar in Burgundy today.

Bernard Dugat purchased the Gevrey vines that produced his first wines in 1975; Py is the maiden name of Bernard’s wife, Jocelyne. In 1996, their son Loïc joined the family business and is now at the helm. He was instrumental in starting their conversion to organic viticulture, for which they gained full accreditation in 2003.

Loïc Dugat-Py, Domaine Dugat-Py

Loïc is passionate about old vines, always searching for old parcels of Pinot Fin or Chardonnay. This dedication has resulted in the domain now owning vines that range from 65 to more than 100 years old in Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune. Consequently, nearly every wine in the line-up is designated either as Vieilles Vignes or Très Vieilles Vignes. They tend to these mature vineyards with meticulous care, using homemade biodynamic teas throughout (they are certified biodynamic). The Premier Cru and Grand Cru sites are horse-plowed. The vines are never trimmed, allowing the canopies to reach a height of seven or eight feet in the summer months.

Loïc says, “Today our climats include 23 acres of Pinot Noir and 3 acres of Chardonnay, including the original vineyards located in Gevrey. We have always produced classic Vins de Garde, deep in color, with explosive fruit and chiseled tannins. I refuse to chaptalize, acidify, inoculate or add anything to juice; sulfur is only added prior to bottling. And while the wines are still deep and powerful, I like to think they have more balance and finesse than ever. Also never elevated, the alcohol rarely surpasses 13.5%, and harvest now occurs on the earlier side to retain freshness and elegance.”

Domaine Dugat-Py ‘Cuvée Cœur de Roy, Très Vieilles Vignes’, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ($170)

Domaine Dugat-Py ‘Cuvée Cœur de Roy, Très Vieilles Vignes’, 2014 Gevrey-Chambertin ($170)

From tiny-yield vines ranging in age from 50 to 105 years old; the crop level here is just 23 hectoliters per hectare. The wine is a step up in intensity and sweetness from the Évocelles, with size to support its substantial ripe tannins for the past decade. Its once substantial fruit now shows a nice finishing dryness laced with bitter chocolate, sweet leather and pie spice.

Domaine Dugat-Py, 2014 Charmes-Chambertin Grand Cru ($890)

Domaine Dugat-Py, 2014 Charmes-Chambertin Grand Cru ($890)

A truly brilliant Gevrey; Dugat-Py’s 2014 Charmes-Chambertin was built using around 40% whole bunch fruit, and remains blessed with a rich bouquet with layers of macerated fruit mixed with a retaining-wall of new oak. The palate is dry on the entry and shows granular tannin as a touch of orange rind with a spice note towards the structured finish that is Mazoyères-like in style.

Domaine Bart

Fifteen years ago, the winegrowers of Marsannay started the process of having part of the appellation upgraded to Premier Cru. At Domaine Bart, which produces as many as nine different Marsannay bottlings in a given vintage, it is believed that 25% and 30% of the appellation is up for this bump upstairs. Pierre Bart, the sixth generation to run Domaine Bart, says, “We are trying to show which climats would be of interest and which ones should remain in the village appellation. My guess is that there will be five or six Premier Crus. probably the largest ones like Champs Perdrix, Champ Salomon, Clos du Roi, Longeroies and Montagne.”

Pierre Bart and Family, Domaine Bart

The Bart domain covers 54 acres, mostly in Marsannay, but with a few parcels in Fixin, Gevrey-Chambertin, Chambolle-Musigny and Santenay. “My grandmother comes from the same family as Domaine Bruno Clair,” explains Pierre Bart. “Part of the vines come from that side of the family, part from my grandfather’s side. The Bonnes Mares and the Chambertin Clos de Bèze mainly come from my grandmother. 35 years ago, when my uncle arrived at the domain, the style of the wines changed. He increased the size of the holding, mainly in Marsannay. He chose to improve quality, both in terms of equipment and in winemaking. Since then we haven’t changed our vision a single iota.”

Domaine Bart, 2014 Chambertin Clos de Bèze Grand Cru ($550)

Domaine Bart, 2014 Chambertin Clos de Bèze Grand Cru ($550)

Clos-de-Bèze may be almost as highly regarded as its southern neighbor Chambertin, whose soils are similar, made up of pebbly, free-draining limestone with a good proportion of clay. Like Chambertin, Bèze makes a wine that is classically Gevrey-Chambertin—perfumed, full-bodied, concentrated and structured, and worthy of being aged for many years. Appellation law allows producers to label wines from Clos-de-Bèze as Le Chambertin (but not the other way around), and while the latter is often considered the apogee of Gevrey-Chambertin, Clos-de-Bèze is the older of the pair. Records show the vineyard, owned and run by the Abbey of Bèze, was already known in the 7th Century, well before it was ceded to the Chapter of Langres, which by that stage had acquired Mr. Bertin’s field, ‘le champ de Bertin’ in the 12th Century.

Believing that his Clos de Bèze tends to taste almost too ready to drink at bottling, Pierre Bart ends fermentation by raising the temperature and giving the wine a couple of powerful punch-downs to fix a bit more tannin. The 2014 may still be in its late youth, showing concentrated, almost brûlée-like blackcurrant, cherry compote and an overflowing spice-box behind a velvety expression where licorice and chocolate come into play alongside musk, truffle and forest floor.

- - -

Posted on 2024.01.06 in France, Champagne, Wine-Aid Packages | Read more...

Producer Of The Year: The Talented Aurélien Laherte ‘Quest For The Perfect Alchemy’

Sparklers To Ring In The New Year

This week (like many of you) we mark the arrival of a new year with the wine style most associated with celebration: Effervescent. At Elie’s, this bubbly occasion is the culmination of a year spent like a cat with a laser pointer as we chase down the best sparkling wines of France and Spain, ending up in familiar appellations in Champagne and some finding off-the-beaten path gems in terroirs where Méthode Champenoise may not be the first words that come to mind. In Alsace, for example, Domaine Valentin Zusslin produces a textbook-perfect Crémant using pure Bollenberg Pinot Noir, while Domaine Michel Briday’s sparkling Burgundy hails from 38 acres spread across the municipalities of Rully, Bouzeron and Mercurey. In Spain, amid the unblemished beauty of the Penedès, Pepe Raventós brainchild winery Can Sumoi has captured the smells and flavors of Catalunya in his remarkable portfolio of pétillant and sparkling.

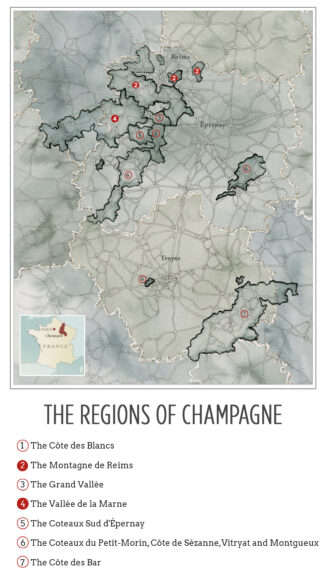

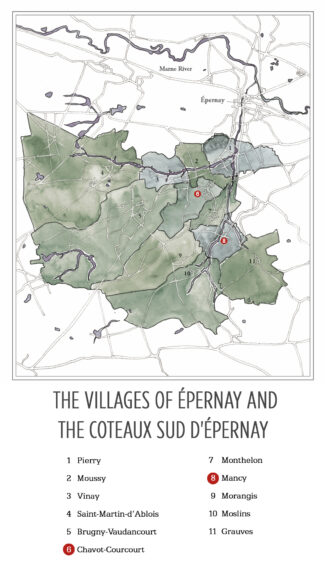

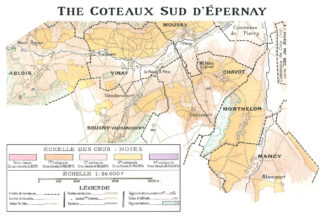

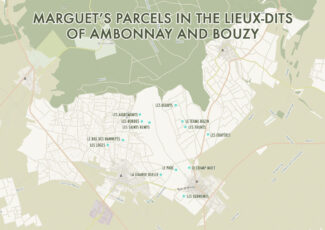

With season of sparkles fully upon us, we will cap the year in our usual fashion—by showcasing the wines of a particularly interesting producer. This year, the talented Aurélien Laherte from Champagne Laherte Frères gets the nod, offering us an array of Coteaux Sud d’Epernay gems that have raised the quality bar in this somewhat lesser-known of Champagne’s 7 ‘regions’, the spiritual home of Meunier. Aurélien also experiments with some of Champagne’s nearly forgotten varietals and is lauded for his attention to lieu-dit expression as well as his mastery of the fine art of blending.

Champagne Laherte Frères

Champagne’s Coteaux Sud d’Epernay

Terroir Fundamentals: Preserving Its Details

When trying to demystify the mysterious—and to ground the ethereal—words like ‘alchemy’ (the ancient pseudoscience of spinning gold from base metals) may seem problematic. And yet, under the nimble hands of Aurélien Laherte, the full range of Champagne’s ‘next-level’ magic takes center stage.

‘Next-level’ because Laherte is one of the most progressive young winemakers in the Coteaux Sud d’Epernay, a sub-region sandwiched between the Côtes des Blancs and the Vallée de la Marne. A champion of organics and biodynamics, Aurélien produces a lineup of blended and single-vineyard Champagnes that expresses the unique identities of his terroirs.

Aurélien Laherte, Champagne Laherte Frères

The quest for perfection is a keystone in the plans of every winemaker, but in Champagne, where warming temperatures are created consistently better harvests and a return to a natural approach is making terroir more and more transparent; the luck of the draw is shifting to the skills of the Cellar Master. Knowing when to blend and when to let an individual lieu-dit shine through is among the most valuable tools in the chest, and when deployed correctly, allows the vintner to create wines worth their weight in gold.

The result is clear, chiseled Champagnes that are created with the sole intention of reflecting the nuances of the plot in which they originate. The estate, with 75 parcels situated in three distinct areas (the southern slopes of Épernay, the Côte des Blancs, and the Marne Valley) is centered in the village of Chavot in the Côteaux Sud d’Epernay. They produce around 150,000 bottles a year, and this week’s offering contains a cross-section of the most outstanding.

Single Variety

Champagne’s Nod To Burgundy

Bordeaux, and indeed much of Champagne, blends grape varieties to create signature ‘house’ wines. In Burgundy, the thinking is different: Burgundies are primarily monocépages, meaning they are made from a single grape variety, often sourced from a single vineyard. In Bordeaux, the monocépage concept is virtually unknown, but in Champagne, most prominent producers will offer at least one or two in their portfolio, Blanc de Noirs or Blanc de Blancs. Frequently they are vintage cuvée produced only in years where a special set of conditions are met and only released in limited quantities.

• Blanc de Blancs

Blanc de Blancs—a term found only in Champagne—is used to refer to Champagne produced entirely from white grapes, most commonly Chardonnay. Pinot Blanc and Petit Meslier can also be used, as well as a number of other varieties permitted in the appellation, but these are much less common.

Chardonnay: ‘Emblematic Cuvée’

Champagne Laherte Frères, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Blanc de Blancs Brut Nature ($59)

Champagne Laherte Frères, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Blanc de Blancs Brut Nature ($59)

100% Chardonnay from the south-facing slopes of Épernay and Chavot, grown on soft clay and chalk and harvested from vines about 35 years old. The wine is fermented in small foudres and barrels with minimal bâtonnage; it undergoes partial (20%) malolactic and is aged on fine lees prior to disgorgement. The zero dosage is balanced by the creaminess of the malo; the wine shows bright tropical fruit flavors, especially mango with a hint of ginger. Disgorged January 2023.

Chardonnay: ‘White with A View’

Champagne Laherte Frères, 2019 Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot ‘Les Grandes Crayères’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($91)

Champagne Laherte Frères, 2019 Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot ‘Les Grandes Crayères’ Blanc de Blancs Extra-Brut ($91)

100% Chardonnay from Chavot mid-slopes where soft Campanian chalk gives these old vines a perfect substratum on their western exposition. This is a single-vineyard cuvée with vines grown using sélections massales and a blend of new and old rootstocks. Disgorgement is done by hand, with dosage at 3 gram/liter. A classic Coteaux Sud Blanc de Blancs showing notes of crème brûlée, apple pie, Jerez-like nuttiness and an extremely fine mousse. Disgorged November 2022. 3928 bottles produced.

Petit Meslier: ‘Vibrant and Expressive’

Petit Meslier is a nearly-forgotten grape of which Laherte is so enamored that he replanted a portion of the clay and silt (with chalk below) mid-slope in the hills of Chavot to preserve the varietal diversity of Champagne. Don’t confuse Meslier with the similar-sounding Meunier; it is a white grape made by crossing Gouais Blanc with Savagnin. Currently grown in small quantities in Champagne, it is noted for its heat resistance and ability to maintain acids during long spells of hot weather and, when vinified as a monocépage, provides tremendous aromatic intensity and depth.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Petit Meslier’, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Extra-Brut ($130)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Petit Meslier’, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Extra-Brut ($130)

100% Petit Meslier. In creating his iconic, all-inclusive blend ‘Les 7’, Aurélien was particularly struck by the ability of his Petit Meslier to stand on its own. From a vineyard called ‘Cépage Oubliés’, it is a blend of several harvests with 40% reserve wine and aged for six months on its lees ‘fût de chêne’, or in oak barrels; it shows honeyed pear, buttered toast and toasted almonds behind an unsurprisingly racy spine of acidity. Disgorged September 2022.

• Blanc de Noirs

In Champagne, Blanc de Noirs mean that the wine is made from either Pinot Noir or Meunier (or a blend of the two), although it’s relatively common to find 100% Pinot Noir. Despite the ‘Noir’, they may be notably ‘Blanc’ since both Pinot Noir and Meunier are red skinned, white-fleshed grapes that produce clear juice. Without being given time to macerate on the dark skins, the wine will be white to the eye, though much more to the palate.

Meunier: ‘Celebrating the Variety’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Vignes d’Auterfois – Vieilles Vignes de Meunier’, 2019 Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Extra-Brut ($91)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Vignes d’Auterfois – Vieilles Vignes de Meunier’, 2019 Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Extra-Brut ($91)

The selected Meunier plots for this wine were planted by the Laherte family between 1947 and 1953 in the villages of Chavot (lieux-dits La Potote and Les Rouges Maisons) and Mancy (lieu-dit Les Hautes Norgeailles). Some of the vines were planted on French rootstock while others are the result of old sélection massale. Aurélien uses traditional wooden Coquard presses; fermentation occurs with native yeast in old Burgundy barrels and malolactic fermentation does not take place. The wine ages up to 19 months on the lees and dosage is between two and four grams per liter; it exhibits marvelous aromas of white peach, violets and verbena. Disgorged November 2022. 4396 bottles produced.

Pinot Noir: ‘Deep and Faithful’

Pinot Noir accounts for 38% of the area under vine in Champagne and is the dominant grape in Montagne de Reims and Côte des Bar. It is frequently referred to as ‘Précoce’ due to its tendency to ripen early, leaving behind the acidity so prized by Champagne makers. It thrives in cool, chalky soil—a hallmark of Champagne’s terroir.

Champagne Laherte Frères, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot ‘Les Rouges Maisons’ Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($91)

Champagne Laherte Frères, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot ‘Les Rouges Maisons’ Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($91)

100% Pinot Noir (harvest 2019) from the prized lieu-dit Les Rouges Maisons planted in 1983 on rich soils of silex, schist and limestone. Malolactic is employed and dosage a scant 2 grams per liter to produce a rich BdN, poised on the palate and showing the austerity, finesse and racy freshness typical of this terroir. Disagorged November 2022. 1698 bottles produced.

Pinot Noir: ‘Intense and Straight’

Champagne Laherte Frères, 2019 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Chamery ‘Les Longue Voyes’ Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($91)

Champagne Laherte Frères, 2019 Montagne-de-Reims Premier Cru Chamery ‘Les Longue Voyes’ Blanc de Noirs Extra-Brut ($91)

Part of Aurélien Laherte’s’ ‘Terroirs’ series, this is the second incarnation of ‘Les Longue Voyes’, a Blanc de Noirs Champagne made entirely from Pinot Noir. The fruit comes from the village of Chamery on the Petite Montagne de Reims, nearly twenty miles from the estate—hence the name, which means ‘The Long Way’. Barrel aged for 18 months with a 4 grams per liter dosage and no malolactic, the nose reveals notes of black fruits, and the palate is tense, tasty and tonic with a persistent saline finish. Disgorged November 2022. 3274 bottles produced.

• Rosé

Credit Madame Clicquot for revolutionizing the (then) relatively small production of pink Champagne. A believer in the idea that a wine should flatter both the eye and the palate, the Grande Dame broke with tradition and re-created the process of making rosé champagne. Before, it was made by adding an elderberry-based mixture to white Champagne, but Madame Clicquot had vines in the Bouzy region of Champagne where she made her own red wine, and she decided to blend this with her still white wines.

This is the most common method of producing rosé Champagne—blending clear white and black grape musts, using between 5% and 15% red wine; it is called a rosé of ‘assembly’. The proportion of red wine can vary, but the white wine must be the majority. Another method of rosé production is the ‘saignée’ method, which involves allowing the must to undergo minimal skin contact, generally for only a couple of hours. This minimal maceration allows the must to develop stronger aromas and flavor profiles while deepening the color. ‘Saignée’ translates literally to ‘bleeding’, which is essentially what the skins are doing into the juice.

Meunier: ‘Strong Identity’

Traditionally used as a blending grape, there are about 26,000 acres of Meunier planted in Champagne, and the variety is rapidly becoming more than an afterthought used for color and balance. In the right soil conditions (calcareous clay with deeper chalk layers) and if allowed to ripen well (leapfrogging the vegetal stage) it can produce a wine that ages remarkably, showing finesse and freshness even after years in the bottle.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Rosé de Meunier’, Extra-Brut Rosé ($61)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Rosé de Meunier’, Extra-Brut Rosé ($61)

100% Meunier, the wine is sourced from vineyards in the Vallée de la Marne and Chavot with an average age of 25 years for the Meunier vinified white and more than 40 years for the parcels selected for the red wine. It is a blend of 30% macerated Meunier, 60% white wine from Meunier and 10% still red Meunier. As a result, it uses both methods of Champagne rosé creation, assemblage (blending) and saignée (bleeding). The wine is multi-layered with a ripe core of red fruit and brisk girdling acids. Disgorged March 2023.

Meunier: ‘Varietal Complexity and Nuances’

Champagne Laherte Frères, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot ‘Les Beaudiers’ Extra-Brut Rosé de Saignée ($91)

Champagne Laherte Frères, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot ‘Les Beaudiers’ Extra-Brut Rosé de Saignée ($91)

Produced entirely from Meunier (harvest 2019) which comes from plots situated in ‘Les Beaudiers’ in Chavot and cultivated using methods which include short pruning for a limited production; manual and painstaking work that requires regular plowing. The grapes were destemmed and macerated for twelve hours, then fermented in barrels on natural yeast without malolactic. The wine shows layers of pomegranate, wild strawberry and rose petals above an exquisite bead and all the depth and density one expects in a saignée. Disgorged November 2022. 1672 bottles produced.

Blending

A Tapestry Of Few Threads

Champagne should illustrate the word ‘synergy’ above all, where the sum of the total is greater than the individual parts. The ideal blend should be the aggregation of positive components; every thread should add to the tapestry’s whole. The blend should always drive toward harmony; Chardonnay is often up front, while Pinot Noir supplies the middle and finish. Other allowable varietals should only appear if they contribute to the primary blend.

This is not a universal outcome, of course, and according to Jean-Marc Lallier of Champagne Deutz, “Some winemakers do not blend; they mix.”

When cellar masters do it right, it is a painstaking undertaking; every tank, barrel and vat is tasted countless times to assess which batch would enhance which. This is the true art of Champagne making—the intimate familiarity with each component in order to align them perfectly.

At Laherte, Aurélien does not have a recipe for a single wine; he blends according to the call from the barrel and each blend has a trademark distinction. He prefers very low dosage, insisting that the wine’s minerality must speak first. Regarding the tedious art of blending, he says, “They’re like people; one needs to be strong, one of them weak; one bitter, one elegant.”

Highlighting Village Chavot’s Terroir: Diversity Of Soil

The commune of Chavot-Courcourt consists of Chavot (in the northeastern part of the commune) and Courcourt (in the central part of the commune), but also the small villages Ferme du Jard, Les Fleuries, La Grange au Bois, and Le Pont de Bois. Among the many folds and hills in the area, the upper reaches are clay-dominant while the soils turn chalkier as you descend. Most of the vineyards in Chavot-Courcourt are located in the northern part of the commune, on slopes formed by the stream Le Cubry.

Aurélien Laherte explains why he farms so many individual parcels in a relatively small area: “Below the village especially is a significant difference in soil types. I have identified 27 terroir-types in Chavot-Courcourt alone and farm 45 parcels. There is no sand, but there is virtually everything else—from chalk to clay to limestone. Between them are countless fine-grained distinctions, so I treat them individually and vinify them separately.”

Les Beaudiers is a vineyard in Chavot where Laherte Frères has old vines of Pinot Meunier (planted in 1953, 1958, and 1965) that are used for a rosé saignée. Other vineyard sites in Chavot-Courcourt include Les Charmées, Les Chemins d’Epernay, Les Monts Bougies, Les Noelles, La Potote, and Les Rouges Maison, all used by Laherte Frères for their Champagnes Les Vignes d’Autrefois and Les Empreintes.

Although Meunier is the dominant grape variety, Laherte also owns a vineyard called ‘Les Clos’ where he plants all seven legally allowable Champagne grape varieties. From this he concocts the individual-vinification philosophy by picking and pressing all seven varietals together.

‘Duality of Terroir’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Empreintes’, 2017 Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot Extra-Brut ($99)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les Empreintes’, 2017 Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot Extra-Brut ($99)

From two parcels in the Chavot lieux-dits Les Chemins d’Épernay and Les Rouges Maisons, each (in Aurélien’s words) ‘exemplifying the quintessence of the Chavot terroir.’ The wine is a classic Champagne blend, half Chardonnay, (of which one-third is Chardonnay Muscaté) from Les Chemins d’Epernay where there are clay soils with a little silt stratum in surface and a chalky subsoil—vine planted in 1957. The other half is Pinot Noir from Les Rouges Maison where the soil is fairly deep with a vital presence of clay, flints and schists; these vines were planted in 1983. With a dosage of 3.5 grams per liter, it is a resonant Champagne with floral top notes and deftly balanced acidity. Disgorged October 2022.

‘Infusion’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Infusion – Meslier & Pinot’, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot Brut Nature ($150)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Infusion – Meslier & Pinot’, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot Brut Nature ($150)

Only 600 bottles were made of this tiny cuvée. The blend is 50% Petit Meslier and 50% Pinot Noir from two plots in Chavot, and it spends 30 months on the lees in barrel before being bottled without dosage. True to its name, the crisp fruit of Meslier is infused with Pinot Noir’s vinosity, and the wine shows green apple, citrus peel, almond and stone flavors that linger through a long, nicely balanced finish. Disgorged October 2022. 669 bottles produced.

‘Tribute to Yesterday’s Wines’

The soléra system of maturation used for Sherry, the famous fortified wine of Jerez, is a cry for consistency from vintage to vintage. The system involves removing wine for release from the last of a series of barrels that contains a blend of every vintage since the soléra was started. The void in those barrels is then filled with wine from another series of barrels, and so on, until there is room in the youngest series of barrels. The wine from the most recent vintage is added to those barrels.

In Champagne, the method used is slightly different; after each harvest, wine is added to the blend, and every time a producer is ready to release a new batch of non-vintage Champagne, he removes what he needs. Over time, the cuvée becomes increasingly complex as the fresh wines of the latest vintage taking on the mature qualities of those that came before it. It is a system used by surprisingly few producers in Champagne, but Laherte Frères is one of them.

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les 7 Soléra’, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot Extra-Brut ($130)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Les 7 Soléra’, Coteaux-Sud-d’Epernay Chavot Extra-Brut ($130)

As the name suggests, all seven allowable Champagne grapes are used in this single cuvée; 10% Fromenteau, 8% Arbane, 14% Pinot Noir, 18% Chardonnay, 17% Pinot Blanc, 18% Meunier and 15% Petit Meslier from a vineyard planted by Thierry Laherte in 2003. He picks and presses all seven together and employs his perpetual cuvée: Les 7 contains wine not only from the current vintage, but draws bits of reserve wine from all harvests dating back to 2005, the year Aurélien took over the domain. All bottles are disgorged by hand with a dosage of 4 grams per liter. The wine shows lemon zest, crystalline green-apple candy and floral notes in a stony infrastructure. Disgorged November 2021. 3621 bottles produced.

‘Return to Basics’

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Ultradition’, Extra-Brut ($54)

Champagne Laherte Frères ‘Ultradition’, Extra-Brut ($54)

60% Meunier, 30% Chardonnay and 10% Pinot Noir from vineyard plots in the Côteaux Sud d’Epernay, Vallée de la Marne and Côte des Blancs where vines average around 30 years. The wine ages in barrels for six months and given light filtration before bottling during the spring time; 6-8 gr/l dosage. The wine offers a complex bouquet of dried apple and toasted walnut; the Meunier lends floral tones and an upper-register smokiness. Disgorged September 2022.

Coteaux-Champenois: Still Champagne

Is It Still Champagne?

The Coteaux-Champenois AOP is dedicated entirely to non-effervescent wine from Champagne and may be red, white or rosé, although the lion’s share is red—Bouzy rouge being the most celebrated. With a warming climate ripening grapes more consistently, Coteaux-Champenois is becoming positively trendy and producers across the 319 communes entitled to make wines under the Coteaux Champenois appellation.

Domaine Laherte Frères, 2018 Coteaux-Champenois ‘Les Rouges Maisons’ Rouge ($73)

Domaine Laherte Frères, 2018 Coteaux-Champenois ‘Les Rouges Maisons’ Rouge ($73)

100% Pinot Noir from the prized Les Rouges Maisons lieu-dit; Aurélien says. “At the domain, we love diversity and we have a naturally curious and imaginative winegrower spirit! After a few years, we are happy to be able to present some Coteaux Champenois to you again. In 2018, the harvest was beautiful, generous, with maturities rarely reached and with a full and intense aroma. It seemed obvious to us to push the maturities on a few plots, in order to seek phenolic maturity and an interesting structure to develop Coteaux-Champenois.”

The wine shows off the chalky terroir in a mineral-driven Pinot Noir filled with the finesse and tension that reflects true Champagne character. Only 854 bottles were made.

Notebook

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay: Middle Grounds, Between Two Giants

The Coteaux Sud d’Épernay is Meunier-rich, with 47% of its 3000 acres planted to this variety, which is sometimes imagined as an ‘also ran’ in Champagne. In fact, Meunier is suited for soils that contain more clay and in terroirs with harsher climatic conditions since it buds late and makes it more resistant to frost. Sandwiched between the powerhouse wine regions Côte des Blancs and Vallée de la Marne, the Coteaux has an identity removed from either one; its terroir is distinctly different from the clay-heavy soils of the Marne and lacks the chalk of that puts the ‘blanc’ in the Côte des Blancs.

Phrasing it succinctly is Laherte Frères proprietor Aurélien Laherte: “Our wines show more clay influence than those of the Côte des Blancs and they are chalkier than the wines of the Vallée de la Marne.”

In short, these Champagnes are uniquely situated to offer the best of both worlds. As a result, the Coteaux Sud d’Épernay has long fought for recognition as entity unto itself, not necessarily a sub-region of its big brothers on either side.

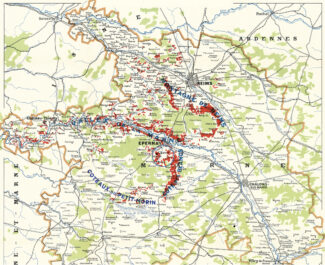

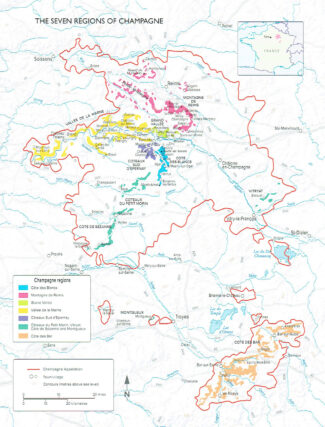

Drawing The Boundaries of The Champagne Region

Having been defined and delimited by laws passed in 1927, the geography of Champagne is easily explained in a paragraph, but it takes a lifetime to understand it.

Ninety-three miles east of Paris, Champagne’s production zone spreads across 319 villages and encompasses roughly 85,000 acres. 17 of those villages have a legal entitlement to Grand Cru ranking, while 42 may label their bottles ‘Premier Cru.’ Four main growing areas (Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, the Côte des Blancs and the Côte des Bar) encompass nearly 280,000 individual plots of vines, each measuring a little over one thousand square feet.