Like so many figures in Greek mythology, Oedipus has been the subject of numerous works of art down the centuries. In this post I’ve collected together a few examples of depictions of Oedipus that I find interesting as part of my ongoing project to keep the experience of reading Sophocles’ play fresh for me after five straight years of doing so.

An immediate thought about bringing these pieces together is that this isn’t the sort of collection one would expect to see in a typical display in a gallery or museum. Museums and galleries (at least in my experience) tend to group artwork by period or by artist. Thematic organisation – the tracing of depictions of a famous mythological figure, such as Oedipus, over time – is not something I’ve really seen very often. Perhaps I haven’t been paying enough attention: in any case, for me as a student of history interested in the longue durée, this is a nice way to approach art history.

My first piece is taken from ancient Greece. It is an Attic kylix (Attica being the land around Athens; Kylix being a type of wine-drinking cup) which was produced around 470 BC. It can be seen today on display in the Gregorian Etruscan museum in Vatican City. In this scene, Oedipus is addressing the Sphinx, the mythical being – half-human and half-lion, who blocks the road to Thebes, refusing to allow anyone to pass unless they can solve its riddle. Oedipus – uniquely – manages to solve the riddle: as a consequence, the sphinx (dramatically) kills itself. One thing I like about the scene depicted here is Oedipus’ contemplative pose: his hand is on his chin, his legs crossed. The sphinx, meanwhile, is in a sense unreadable: he has no eyes! He also stands high over Oedipus, on top of a column, but of course his supremacy will not last. Contemplative Oedipus – who certainly doesn’t look like any kind of aggressor or dethroner in this scene – will emerge triumphant over the sphinx in due course.

There have been many artistic depictions of Oedipus’ meeting with the sphinx. Perhaps the most famous is a painting by the French symbolist Gustave Moreau. I happen to prefer this, by another Frenchman, Ingres. It’s a rich scene: the use of light and dark colour is obviously striking, and the narrowness of the pass into Thebes (which can be seen in the background) is clearly evident. Oedipus himself attracts the eye: he is quite young here, but strong, and his pose exudes confidence and boldness. He also looks like he has no trouble being matter-of-fact. He’s dealing here with a riddle you almost sense he can solve – and I think the rather perturbed expression on the face of the sphinx reflects this. What, meanwhile, is the reaction of Oedipus’ colleague in the background supposed to signify? Fright, in all likelihood: at the bottom of the picture, a skull and crossbones clearly show the unfortunate fate of those who fail to solve the sphinx’s riddle. This draws Oedipus’ phlegmatic daring all the more clearly into focus.

A quite different depiction of Oedipus’ meeting with the sphinx is presented by Fabre here. Here again Oedipus is strong and muscular, but this time he seems assertive rather than contemplative. He is also set more against the background of the wider (pleasantly rustic) landscape, high up in the mountains, with the city nowhere in sight. The body position of the sphinx makes it look almost ready to pounce on Oedipus, yet this sphinx seems somehow less imposing and menacing: its bodily dimensions aren’t as intimidating as they might be, and (for me) it doesn’t command the space of the painting in a way the sphinx of Ingres – from its dark corner – does.

Brodowski’s Oedipus and Antigone (above) depicts a scene from Sophocles’ Oedipus sequel, Oedipus at Colonus. Here Antigone, Oedipus’ daughter, guides her father as he wanders around in exile outside his city. The dark clouds and dark rock in the background betoken the gloom that has descended upon Oedipus, but also the darkness that affects him personally: he is now blind. The pair look courageous and strong, despite Oedipus’ predicament. Other paintings of this scene depict Antigone looking lovingly at her father: here she is unabashedly leading the way, looking ahead (or to the side), perhaps, to see where they might go next. She, the daughter, is now the lead figure in their relationship.

In this quite different painting of Oedipus and Antigone from 1812, Eckersberg presents a more doting and concerned Antigone and a more elderly Oedipus who is visibly more frail. This Oedipus nonetheless shoulders the burden of carrying some heavy clothing on his back, while Antigone walks more freely, albeit while expending energy tending to her father. I love the bright colours in this scene, but also the way Eckersberg manages to capture the melancholy of both characters and the tenderness between them. On they go, in sadness, across the bridge.

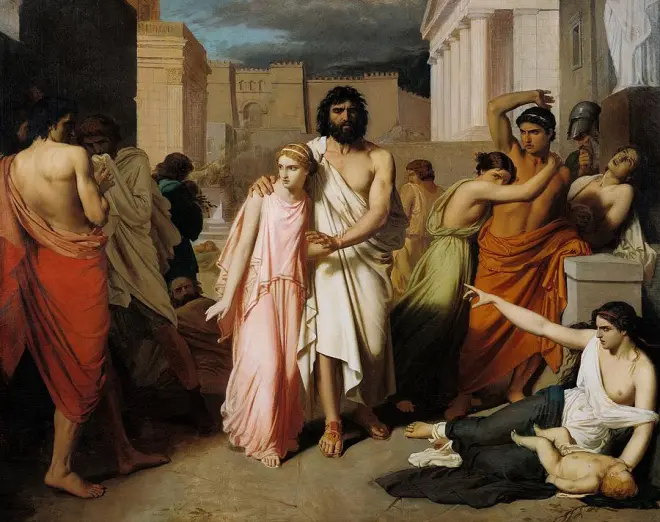

My final Oedipus and Antigone conjures an altogether different impression. Here, in Jalabert’s painting, they walk together through the crowded and chaotic city streets. Antigone leans in toward Oedipus, as if for protection, while towering Oedipus stands strong and tall over the other figures they pass by. His dominant physique suggests his regal credentials and yet, of course, he is now blind and dependent on his daughter. Others – presumably aware that he is a cursed figure – pull away from him in seeming disgust, or, in the case of the woman depicted in the bottom right of the painting, stare at him forbiddingly while pointing toward him. This is a sobering reminder of how Oedipus, once the hero of his city, is now an outcast.

Gagneraux here presents another scene from Oedipus at Colonus. Oedipus, mourned by his distraught children, seems on the brink of death here. A number of others – a soldier, a beggar woman, a mother and child – loiter around the edges of the family, perhaps in sympathy, perhaps in confusion. We see the city once more in the background, and the artist conveys with clarity how deeply loved Oedipus is by his family members.

Another French neoclassical painting with some very clear stylistic similarities to Gagneraux, Giroust’s Oedipus at Colonus depicts a similar scene of mourning. This time only Oedipus’ son Polynices and his daughters Ismene and Antigone attend to him in his distress, while he sits outside what looks like a temple. Polynices wants Oedipus to return to Thebes: he needs help to defeat his vengeful brother Eteocles, who has seized control of the city since his father’s departure. (Tragedy, alas, will mar the fortunes of both brothers, and indeed both sisters: it is not just Oedipus who will suffer).

From French neoclassicism, I turn now to this quite different piece by the surrealist Max Ernst, which was composed at a time when the work of Sigmund Freud (featuring the Oedipus complex) had caused the Oedipus story to be viewed in new and different light. An extended reading of what might be going on in the painting is offered here. Simpleton that I am, I find it baffling.

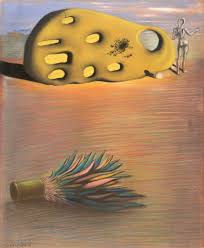

Continuing the Freudian (and surrealist) theme, here is Dali’s Oedipus Complex. This painting seems to be not so much about Sophocles’ Oedipus as it is about Freud. As with so many of Dali’s paintings, it’s difficult to figure out what is going on and I would be lying if I said I found it one of his most captivating pieces. I am tempted to speculate, though, that the large yellow object depicted at the top of the painting could be a depiction of the human brain, with holes signifying areas of unconsciousness. But I shouldn’t speculate, as I’m probably wrong.

Linda Mota’s terrifying contemporary piece marks a renewed focus on Sophocles’ Oedipus himself, here depicted in frightening agony. Blood streams down his face and his facial features are distorted, in a way that reminds me of the facial disfigurement experienced by the central protagonist of the film Vanilla Sky. This Oedipus seems almost trapped within the painting itself, stuck there in agony.

Finally, Alicia Besada’s recent Oedipus evokes the pity of Sophocles’ character. He cowers, shielding himself from the light, apparently naked. I particularly like the funky elements in his skin tone here, but also the way Besada offers a vision which is somewhat redolent of older depictions of Sophocles’ hero, which capture his sadness, desolation and misfortune.

So that’s it: my (very) brief and incomplete survey of Oedipus in art. Perhaps I should just add that I’m certainly no art historian – but I guess that will be obvious to anyone who has read this far.