Happy Memorial Day!

Memorial Day in years gone by was often celebrated by parades and local festivals – and incredible homemade ice cream. An old-time favorite was Maraschino Cherry Ice Cream.

I tend to think of Maraschino cherries as a cocktail garnish (or an ingredient in canned fruit cocktail), but Maraschino cherries were a popular recipe ingredient in the early 1900’s. Back then the cherries were a pricey delicacy, and a popular ingredient that hinted of sophistication and class.

The recipe I adapted was in a hundred-year-old Pennsylvania church cookbook, and it was incredibly easy. This ice cream recipe didn’t require any cooking; I only needed to combine cream, sugar, and lemon juice, and then chill for a few minutes before putting the mixture into the ice cream maker (the cherries are added after the ice cream is frozen). I actually worried that the recipe was too easy, but my fears were totally unfounded. The ice cream was awesome.

The festive Maraschino Cherry Ice Cream was sooth and creamy, and oh so rich, with embedded pieces of Maraschino cherries adding a fun texture and the wonderful nuanced tartness.

My husband and I did not eat all of the ice cream on the day we made it, so we put it into the freezer in our refrigerator – and had a wonderful treat for the next several days. The ice cream texture remained smooth (and unlike what happens when some homemade ice creams are stored, no large granules of ice developed). The inclusion of lemon juice in fruit-flavored ice creams like this one is an old-fashioned way of minimizing the likelihood that large ice granules will develop – and it worked perfectly.

Here’s the recipe updated for modern cooks:

Maraschino Cherry Ice Cream

1 1/ 2 cups sugar

1/3 cup lemon juice

1 quart (4 cups) half and half

1 pint (2 cups) heavy cream

1/2 cup Maraschino cherries, coarsely chopped

In a large bowl, stir the lemon juice into the sugar. Add 2 cups of the half and half, and stir until the sugar is dissolved, then add the heavy cream and the remaining half and half. Stir to combine. Chill the mixture in the refrigerator (or put into the freezer for 15 minutes), then put the mixture into the ice cream maker, and follow the manufacturer’s directions.

After the ice cream is frozen, stir in the chopped Maraschino cherries. Repack in ice in ice cream maker (or put in the freezer) for two hours.

Note: This recipe is for a 4 quart ice cream maker. Adjust amounts if another size of ice cream maker is used.

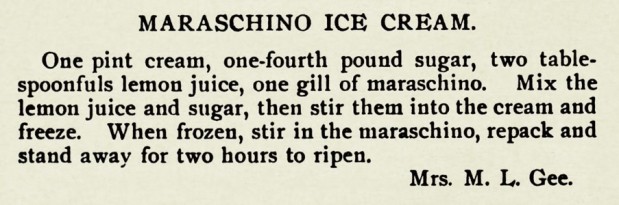

And, here is the original recipe: