By Rebecca Wardle

The Early Bronze Age Period 3 site, Bush Barrow, also known as Wilsford G5, is a part of the Normanton Down barrow group in Wiltshire; a group of round barrows which form a cemetery (Lawson et al 2010, Pastscape 2011). Located less than ½ a mile south of Stonehenge the site, with its wealth of grave goods is of high archaeological significance (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society n.d.).

Bush Barrow (Flickr)

Bush Barrow, a round barrow earthwork measuring 3.3m high and 10.5m in diameter has breaks in its incline, suggesting that it has been developed further over time (Pastscape 2011). It was first excavated on the 10th or 11th of July 1808 by William Cunnington on behalf of Sir Richard Colt Hoare, of Stourhead House, who backed the excavation financially (Lawson et al 2010, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society n.d.). A vast number of barrows at the Normanton Down site were excavated by Cunnington and Hoare, who can be described as “pioneer excavators” (Lawson et al 2010, 9). Prior to the 1808 excavation it is believed that farmers may have attempted to excavate the site, a fact which is worth considering when attempting to draw conclusions about Bush Barrow as their actions may have partially disturbed any finds (Wiltshire Heritage Museum 2007). After Cunnington and Hoare’s excavation of the site, Bush Barrow has been left largely alone aside from when, in April 2010, it was surveyed as a part of English Heritage’s Stonehenge WHS Landscape project, at a scale of 1:1000 (Pastscape 2011). Due to the lack of recent excavations at the site, observations of the site still rely heavily on the observations made, recorded and published in Cunnington’s account. The reliability of this account is questionable as it was written purely by Cunnington, with only a small amount of editing being done by Hoare (Lawson et al 2010). However, despite Cunnington’s lack of archaeological method his “records were exceptional for their time” (alwson et al 2010, 7),, and it has been suggested that he was similar to many of today’s archaeologists in his prejudice-free way of thinking, possibly a result of the fact that he wasn’t highly educated and so had not been indoctrinated with the pre-conceptions of the late 18th century. Despite his lack of the highest standard of education, Cunnington appears to understand that we, as archaeologists, cannot position ourselves in a frame of mind that allows us to think exactly like those in the past, meaning that we therefore have a modern perception of events which is bound to subconsciously impact upon our interpretation of archaeological sites and finds (Lawson et al 2010).

As would be expected of a round barrow, Cunnington unearthed a skeleton during his excavation of Bush Barrow (Pastscape 2011). The position of this inhumation is not known for certain as neither Cunnington nor Hoare saw fit to create a diagram of the burial as doing so was “not yet the practice” (Lawson et al 2010, 9). Therefore modern archaeologists have been left to deduce the true positioning of the burial; whether it was in a crouched or extended position. Previously the inhumation was believed to of been extended but this did not fit with the period that the skeleton is from (thought to be between 1900-1700 BC from the grave goods typology) as other burials from that period tend to be crouched (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society n.d.). Further evidence for the skeleton being crouched can be found in the fact that, due to the rarity of extended skeletons discovered during this period, it is almost certain that, had the skeleton been extended, Cunnington would have recorded this in his manuscript letter (Lawson et al 2010). Therefore modern interpretation of the site considers the inhumation to have been extended. Future investigation of the skeleton using modern scientific tests cannot happen as it has not been preserved and so facts such as the skeletons sex (believed to be male) have to be assumed based on Cunnington’s records (Lawson et al 2010). Other finds, such as the “small rings of bones”, have also been lost and so further investigation into their origins is not possible (Lawson et al 2010, 15). Despite the loss of these highly valuable finds, many more important finds survive and are now being preserved in Devizes Museum (Pastscape 2011).

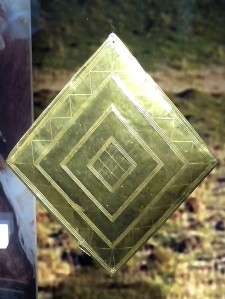

Gold Lozenge from Bush Barrow (Wikipedia)

Other finds, the majority of which are highly decorated with patterns such as Vandyke, include bronze and wood fragments, thought to be the remnants of a shield or helmet as well as an Iron Age brooch, belt hooks, daggers and bone (Wiltshire Heritage Museum 2007, Pastscape 2011, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society n.d., Lawson et al 2010). As with the skeleton, the interpretation of the bronze and wood fragments found at the site has also changed (Pastscape 2011). Modern reconstructions of the excavation show the distance from the skeleton to the fragments, 18 inches, to be too far for the fragments to be considered to be some form of armour, such as a shield or helmet, as these are more likely to have been buried attached to the body (Lawson et al 2010). Instead, modern interpretation suggests that the fragments are part of a dagger or knife.

The daggers discovered at Bush Barrow are also of large importance as two of them are the largest from that period to be discovered and the other dates back 200 years further than the other grave goods, suggesting that it may have belonged to an ancestor, possibly someone who played a role in the construction of Stonehenge, and so may have been of sentimental significance (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society n.d.). Ancestry and family are key aspects of the Normanton Down barrow group as two nearby barrows are believed to possibly be the graves of family members of the Bush Barrow skeleton as they too contain high-value artefacts and the possibility of secondary burials in Bush Barrow also exists (Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society n.d., Lawson et al 2010).

Bush Barrow was, until 1995, believed to be of the same period of nearby Stonehenge. This has been disproven by a new excavation of Stonehenge which implied that the site of Bush Barrow was, in fact, younger than Stonehenge by quite a few centuries. Stonehenge is believed to be Period 1 Chalcolithic whereas Bush Barrow, as previously mentioned, is seen to be Bronze Age Period 3 (Lawson et al 2010).

Current thinking suggests that Bush Barrow is, as it was when it was first excavated in 1808, a significant site in understanding the Bronze Age period due to the apparent high status of the burial (evident due to the rich nature of the finds) (Lawson et al 2010, Pastscape 2011). If anything, the site has become increasingly significant in recent years as its recently been dated as younger than Stonehenge and the discovery of the fact that one of the daggers belonged to the ancestors of the unearthed inhumation demonstrates how people in the Bronze Age kept and preserved items for sentimental purposes (Lawson et al 2010, Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society n.d.).

Bibliography

Lawson, A.J., S. Needham & A. Woodward, ‘‘A Noble Group of Barrows’: Bush Barrow and the Normanton Down early Bronze Age cemetery two centuries on’. The Antiquaries Journal, 90, (2010), 1-39.

Pastscape, Bush Barrow (2011). Available online: http://pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=943060&sort=4&search=all&criteria=bush%20barrow&rational=q&recordsperpage=10# [Accessed 3/11/15].

Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Bush Barrow (n.d.). Available online: http://www.wiltshiremuseum.org.uk/galleries/index.php?Action=3&obID=89&prevID= 25 [Accessed 3/11/15].

Wiltshire Heritage Museum, Wilsford G5 (2007). Available online: http://www.wiltshireheritagecollections.org.uk/wiltshiresites.asp?page=selectedplace&mwsquery=%7BPlace%20identity%7D=%7BWilsford%20G5%7D [Accessed 4/11/15].