Depending on how you look at it, either a lot or not very much has changed about the way bikes shift gears since the mid-19th century.

A lot has been refined along the transmission path, in which your feet push cranks, those cranks turn a big gear, and a chain connects that big gear to a smaller gear on the rear wheel. Shifting has picked up lots of improvements, be they electronic or wireless, as have derailleurs and internal gearboxes. Materials and tolerances have only improved over the decades.

But in almost all cases, you're still manually adjusting something to move the chain and change gears, depending on the resistance you're feeling on the bike. Even the most outlandish recent ideas still involve indexed movement between different-sized gears.

That's why "Automatic Transmission System for a Bicycle," a US patent filed by Haven Mercer and published on November 23, has caught the attention of bicycle enthusiasts, myself included. If it works like it says it does (as shown in a brief video demonstration) and can be produced as a reliable product at scale, it could make for some interesting bikes. It's not meant to replace manual shifting entirely, the patent author told me, but it could allow for bikes that go up hills and speed across flats without much thought at all from the rider. It might even offer some e-bike efficiency.

It also looks, at a glance, like a nightmare to clean and maintain, but it's a prototype, so give it some time.

Shifting with your feet

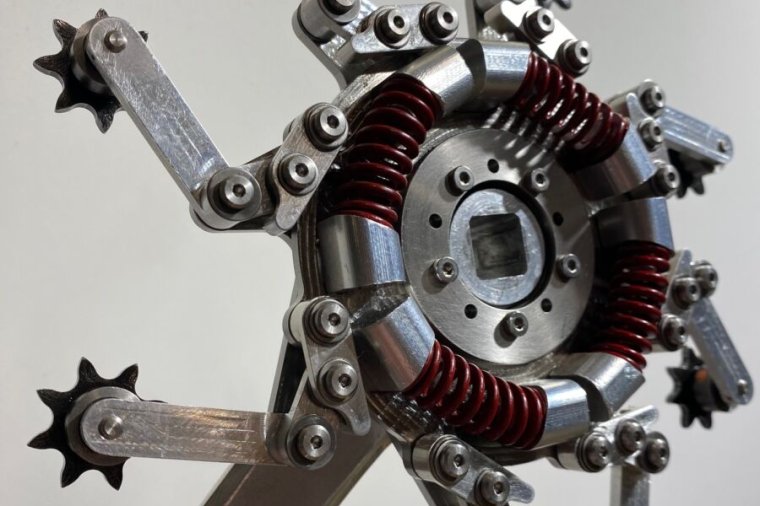

Mercer's system takes the chainring and rear gear and makes them able to expand and contract based on torque. In the front, it does this by replacing a single ring with eight pulley wheels, pushed to their longest extension when there is no tension on the cranks by springs. Each of those pulleys is on a one-way bearing so that when torque is put on the cranks (to go faster or climb a hill), the springs compress, the pulleys fold in, and the whole front element becomes smaller.

On the rear hub, six pulley wheels are pulled into their smallest size by the springs. When force is applied, the pulleys move out and the sprocket as a whole expands. The gearing (so to speak) adjusts as the rider applies and removes torque from the pedals.

There are two chain tensioners below the rear mechanism. They both pick up slack when the front and rear are expanding or contracting at different rates and guide the chain as it comes in at different angles from the front chainring. Mercer's patent suggests a few different setups an automatic-gear bike could have, including with traditional front derailleur cages, a small guiding sprocket in place of a front cage, and other configurations.

-

Diagram of the front chain element in Haven Mercer's patent application.USPTO / Haven Mercer

-

Diagram view of the rear chain element in Haven Mercer's patent application.USPTO / Haven Mercer

-

A single view of a somewhat built-out drivetrain using automatic transmission cogs.USPTO / Haven Mercer

-

An illustration of how the automatic gearing works, with the front and rear elements expanding and contracting as pressure is applied and removed.USPTO / Haven Mercer

-

Under-bike view of the system. Mercer notes that his system keeps the chain in a single plane, which might lend itself to easier mud-guarding and other developments.USPTO / Haven Mercer

-

A rear view of the front chain element in Haven Mercer's prototype.Haven Mercer

reader comments

219