I used to always wonder as a child as well why there were no ‘impressive’ creatures in Europe and why most of the big animals were in Africa. The truth, that I only properly (re)discovered this summer, is that all sorts of magnificently large creatures termed ‘megafauna’ existed on all continents, including Europe. The straight-tusked elephant, for example, ranged across all of Eurasia from Spain to China. Now if you mention there were once elephants in Spain, some people would look at you as if you’re crazy.

It’s not that all creatures were found everywhere of course. There were many that were unique to continents, but certain continents had similar wildlife. For example, European wildlife used to be similar to North American wildlife (also dwindled in the present day) because 2 million to 10,000 years ago, sea levels were so low that animals could walk across from Europe to North America across the Bering Strait – the narrowest point of ocean between Russia and Alaska, about 80 km wide. And what was true was that each continent was rich with impressively large animals at one stage. This world today where British wildlife is mainly hedgehogs, wild rabbits, birds and deer – nothing that will blow your socks off (as much as we love them, let’s be honest) – is not a status quo we could have arrived at without human intervention. It’s also a regrettable status quo. We can only learn if we feel the loss of our mistakes before.

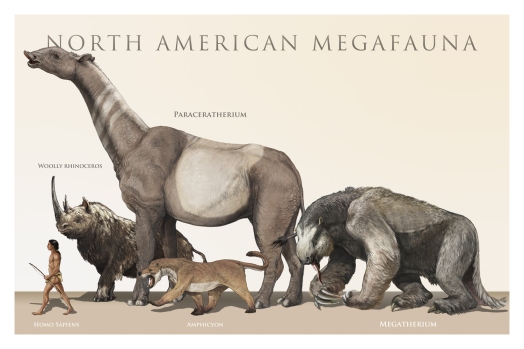

People think it was dinosaurs and then animals of today. No, sir. No, madam. There were many others. Let me take you on a brief safari via some drawings and computer graphics below of megafauna.

Welcome to the Pleistocene

In the Pleistocene epoch, 10,000 years ago, there were giant sloths, mastodons (part of the elephant family but distinct from mammoths), cave lions (European cave lions were slightly bigger than lions today and American cave lions were much bigger), aurochs (large wild cattle, modern domestic cattle descended from it), giant polar bears, giant camels, giant armadillos etc. etc. etc! Perhaps the most famous that people do tend to know about are sabre tooth tigers.

You can also watch the BBC documentary ‘Monsters we Met’ to see some really neat computer-aided recreations. I think the documentary should actually be called ‘Monsters they met’ since we’re the ones who killed these creatures so aggressively (see at 24 mins – an unsuspecting giant sloth has never seen humans before and is not scared because they’re so small and then gets speared to death).

So why did megafauna disappear?

In ‘The World without us’, Alan Weisman explains the work of Paul Martin, a prominent geoscientist whose work spanned many fields. Paul Martin is best known for his theory on the extinction of megafauna – essentially the ‘overkill’ hypothesis. Humans hunted megafauna at a rate that they weren’t able to reproduce and keep up. The only place megafauna has survived to some extent to the present day is in Africa where people traditionally have lived in harmony with nature. Megafauna in the ‘New World’ (basically not-Africa) were also easier hunting targets: indigenous species in the New World did not evolve in the presence of humans so had not developed the same natural wariness exhibited by similarly large species in the Old World (Africa).

Martin’s ‘overkill’ theory is not without its critiques of course. But it is a plausible data-grounded theory that absolutely deserves attention and is now gaining wider acceptance as more evidence surfaces. Many Clovis (an Ancient North American people – ancestors of today’s native americans) sites have been found where there are skeletons of mammoths with spear heads in them. Models developed after the theory have also found support for it. For example, Alroy (2001) independently ran simulations in a model and concluded that ‘homo sapiens growth rate and hunting ability almost always led to mass extinctions, with hunting ability being the most important of all parameters’. Big animals are particularly susceptible to extinction because gestation periods are longer and they require more resources to survive.

“The inverse relationship between body size and population size plays a powerful role in increasing the risk of extinction faced by larger animals” – Grayson

For a short but comprehensive discussion on theories of extinction, I point you to the paper: Examining the Extinction of the Pleistocene Megafauna by Robin Gibbons of Stanford University: http://web.stanford.edu/group/journal/cgi-bin/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Gibbons_NatSci_2004.pdf (just 4 pages long!). Gibbons essentially says that a combination of climate change and hunting likely caused the extinction of megafauna. Megafauna birth rates can be lowered significantly when climate changes and the timing of seasons changes too.

Why it this still incredibly relevant?

Once again, climate change and hunting are prevalent and escalating. Poaching is not a ‘solved’ problem at all. In fact, the World Wildlife Fund says that ‘rhino poaching has increased dramatically in the last few years’, and ‘large quantities of African ivory, for example, are still finding their way to illegal markets in Africa and beyond. Elephants are also killed for their meat and hides’. Never underestimate the impact hunting can have. When Christopher Columbus set foot in America, there were 60 million bison. In 70 years, after killing for horns and sport, just 500 wild buffalo remained. 60 million to 500!!! (BBC Documentary).

Moreover, there is the very powerful force of habitat destruction in play which is a bigger destructive force than hunting in some cases. If we keep taking all the land to build our cities, our highways, our fields, our farms, what land and resources are there left over for other large creatures? Creatures that naturally migrate hundreds of miles now have small corridors to travel in and patches of land to graze on. And there are way too many patches of land where they face risks of being shot down to feed the demand for products bought by unethical and unaware consumers (I’m sorry, I really don’t care who I offend when I say it is not cool to buy ivory products or tiger products). The Pleistocene megafauna are gone because of our ancestors. The creatures today are going because of us.

In my next blogpost, I will look at what we can do individually and collectively to prevent more extinction tragedies.

Even a hundred years after Columbus there wasn’t yet a permanent European settlement in North America; the plains wouldn’t see significant encroachment for another two hundred years past that.

The ‘500 remaining’ buffalo point seems reliably attributed to the late 19th or turn of the 20th century, making your ’70 year’ number less than one fifth the actual time.

The interim solution is virtual reality. The long term solution is different. I’m serious. I think about this a lot, pertaining animal extinction, the concretification of our planet, and overuse of its resources.

Within the next 5-10 years, virtual reality will begin to revolutionize how young people spend their time. Within 20 years, many humans will spend the majority of their time in simulations. This behavior will begin to offset the anthropogenic cost incurred by our planet. There will be a specific day in the future on which the growth of this offset will surpass the growth of cost of human proliferation.

Wildlife will have fleeting moments to regain territory before the eventual rise of inorganic animation. Thenceforth, Earth’s orbit will begin to be intentionally downgraded by terrestrial activity. The surface temperature will rise significantly, making life difficult for much of the remaining organic life.

In the long run, the planet will largely become a host for what we would describe as machines, and the remaining remnants of organic evolution will extremophile bacteria, and sequences proteins and DNA stored for historical reasons. At this stage, at long last, in case it wasn’t clear, humans will no longer be a problem.

Remarkable forethought, remarkable.

But i hope humans will survive extremophile parasites as we have just now discovered way to poke holes at bacteria cell wall, from which there is no defense mutation for bacteria

We should’ve been the Section A Woolly rhinocerous! Interesting article.

Spectacular Article. Being very interested in paleontology myself, hearing of such magnificent creatures is astounding, and knowing humans once walked with them and hunted them is even more astounding. It is truly sad that we cannot witness these creatures for our selves in current time.