Birdfinding.info ⇒ Among the most numerous bird species, Wilson’s Storm-Petrel occurs nearly throughout the Atlantic, Indian, Pacific, and Southern Oceans—though it is localized or scarce acrosss most of the Pacific. Especially numerous along the Atlantic Coast of North America, where it is expected on most pelagic trips from May to October, and regularly appears in inshore waters. Also common in Australian and New Zealand waters during April and October-November. Much less common in the North Pacific—where it is regularly found on pelagic trips and offshore ferry routes in Japanese waters, and among the hordes of storm-petrels in central California waters in the fall. (For the South American form, see “Fuegian Storm-Petrel”.)

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel

Oceanites oceanicus

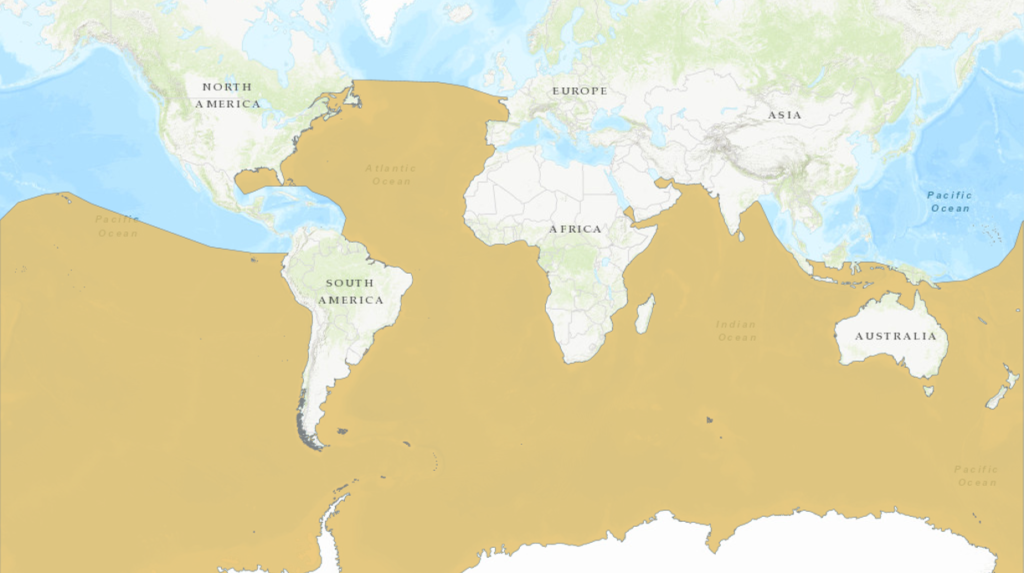

Breeds in southern South America, Antarctica, and many subantarctic islands. Disperses nearly throughout the world’s oceans.

Comprises two distinct forms:

Typical “Wilson’s” (oceanicus and exasperatus) breeds in Antarctica and archipelagos of the Southern Ocean, and migrates to the North Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans.

“Fuegian” (chilensis) breeds in southern South America and the Falkland Islands, and disperses to the Humboldt Current and southern Atlantic.

Approximate distribution of Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. © BirdLife International 2018

Breeding. Typical Wilson’s breeds from November to March (eggs laid in December-January) on rocky cliffs and boulder fields of Antarctica and various subantarctic island groups, including: South Shetland, South Orkney, South Georgia, South Sandwich, Bouvet, Crozet, Kerguelen, Heard, Macquarie, and Balleny.

On the Antarctic continent, it is thought to breed in most coastal regions with suitable habitat that become ice-free during the austral summer—especially numerous on the Antarctic Peninsula.

The “Fuegian Storm-Petrel” breeds mainly from December to March in the Andes of central Chile (from Coquimbo to Maule), the fjordland region of southern Chile, the eponymous Fuegian Archipelago, and the Falkland Islands.

A 2004 estimate of the global breeding population of Wilson’s Storm-Petrel (including “Fuegian”) was in the range of 4,000,000 to 10,000,000 pairs, which would translate to approximately 12,000,000 to 30,000,000 individuals (i.e., breeders and nonbreeders).

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel on its breeding grounds. (Haswell Island, Antarctica; December 2015.) © Sergey Golubev

Nonbreeding. One of the principal differences between typical Wilson’s and “Fuegian” is their migratory tendencies. Typical Wilson’s is highly migratory, as the vast bulk of its populations travels from Antarctic breeding areas to northern temperate regions each year. In contrast, “Fuegians” are either resident or short-distance migrants, remaining around their southern temperate breeding areas or traveling to the southern tropics.

During the austral winter, from April to October, typical Wilson’s migrate north into each of the three major oceans. The largest numbers migrate to the western North Atlantic, and apparently much smaller but still substantial numbers migrate to the Indian and North Pacific.

Migrants in the Indian and Pacific Oceans follow a pronounced clockwise rotation, with the majority migrating north on a westerly path in April, then moving east in July and August, then turning south in September and October. In the Atlantic, the vast majority appear to remain westward throughout their migrations—although a very small percentage passes through African and European waters, mostly on the southbound return.

Most of the global population passes most of the boreal summer, from May to September, over or near the eastern continental shelf of North America, from North Carolina to Newfoundland. Much smaller numbers remain in warmer water south to the Bahamas, or enter the Gulf of Mexico (mostly east of the Mississippi River mouth), or continue north to Labrador waters. Records indicate that at least a few press north into Davis Strait, and a few wander up the St. Lawrence River, appearing around Quebec City in October.

“Fuegian Storm-Petrels”, O. o. chilensis, such as this one, often appear at inland locations in the Andean foothills of central Chile, where they are now known to nest. (Los Queñes, Maule, Chile; March 21, 2017.) © Matías Caviedes

In European waters, it was long regarded as an exceptional vagrant, but increased offshore coverage has shown it to be uncommon north to Ireland, and likely a rare but regular straggler north to Iceland, the Faroes, and the Shetlands.

Most migrants to the Indian Ocean apparently follow a clockwise rotation, moving northward through African offshore waters to the western Arabian Sea, then proceeding east to India, and ultimately returning south through the offshore waters of Western Australia.

Observations of typical Wilson’s in the North Pacific have increased such that substantial numbers are known to occur annually from May to August in Japanese waters and from August to October off of western North America from Washington to Baja California. There have been only sparse records from the central Pacific.

A portion of the “Fuegian” population remains year-round in the breeding range: in the Humboldt Current waters of central and southern Chile and in the southwestern Atlantic off of southern Argentina and the Falkland Islands.

A substantial portion of the population disperses more widely in the South Pacific and South Atlantic. In the Pacific, “Fuegian” occurs regularly north to Ecuadorian waters, and at least occasionally to the Gulf of Panama. In the Atlantic, some migrate north to Brazilian waters, and some move east to the Benguela Current waters off of southwestern Africa, and at least occasionally east into the Agulhas Current off of eastern South Africa.

Identification

A small storm-petrel that resembles many others and is widespread enough to occur with all of them. In many parts of the world’s oceans, it is seasonally the commonest storm-petrel.

Wilson’s Storm Petrel, showing U-shaped white rump band, faded blond bars on upperwing coverts, and long legs projecting past its square-tipped tail. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 30, 2020.) © Justin Bosler

Like many of the northern storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) that occur with it during the boreal summer, Wilson’s is dark-brown overall, with an even white band across the rump that extends partway down the sides of the rump to the undertail. The tail is shallowly notched, and often appears squarish, or rounded when fully fanned.

Also like these and other dark storm-petrels, Wilson’s typically show a contrasting pale diagonal bar on the upperwing coverts. Juveniles and freshly molted adults show a bold, crisp, silvery bar. With feather-wear, the bar turns blonder and browner.

Wilson’s can be distinguished from the northern storm-petrels by its proportionately longer legs, which usually extend well beyond the tip of its tail, and by the yellow webs between its toes, which are often visible when it feeds, dangling its feet.

Wilson’s Storm-Petrels, a flock engaged in typical foraging behavior, pattering their feet in the water. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 13, 2011.) © Holly Merker

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, showing pale bars on upperwing coverts. (Offshore from Poor Knights Islands, New Zealand; October 25, 2021.) © Scott Brooks

Wilson’s also differs from most northern storm-petrels in its typical flight patterns. When traveling, it often resembles a swallow, gliding on flat wings, with occasional bouts of rapid shallow wingbeats. When feeding, it often flutters or holds its wings in a deep “V” while pattering its toes in the water.

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, in a typical feeding posture, pattering its feet in the water and holding its wings in a deep “V”. (Offshore from Vitória, Espirito Santo, Brazil; April 7, 2018.) © Leopoldo Pivovar Plotecya

Among the southern storm-petrels (Oceanitidae), Wilson’s resembles the closely related Elliot’s and Pincoya Storm-Petrels—including their flight patterns, long legs, and yellow webbing—but it differs in having essentially all-dark underparts: Wilson’s usually shows no white plumage on the belly or underwings.

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, showing square-tipped tail (appearing wedge-shaped in this posture) and long legs. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; June 7, 2018.) © Steve Kelling

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, showing essentially all-dark underparts. (Offshore from South West Rocks, New South Wales, Australia; April 3, 2021.) © Jodi Webber

“Fuegian Storm-Petrel”. The greatest potential for confusion is between the widespread typical form of “Wilson’s” (i.e., oceanicus and exasperatus) and the more localized “Fuegian” (chilensis) form of South American waters and east to southern Africa.

On average, “Fuegian” differs from typical “Wilson’s” in being slightly smaller and usually showing a narrow whitish stripe on the underwing coverts. However, neither of these distinctions is reliable: the size difference would require measurements to verify and “Fuegian” sometimes has all-dark underparts.

“Fuegian Storm-Petrel”, O. o. chilensis, an ideal individual for field identification, showing a bold white stripe on the underwing coverts. (Offshore from Valparaíso, Chile; June 29, 2013.) © Pablo Andrés Cáceres Contreras

“Wilson’s Storm-Petrel”, O. o. oceanicus, showing typically unmarked underwings. (Offshore from Port MacDonnell, South Australia; March 2017.) © Craig Greer

“Fuegian Storm-Petrel”, O. o. chilensis, showing a thin, indistinct pale stripe limited to the inner underwing coverts—not readily distinguishable from typical “Wilson’s”, O. o. oceanicus. (Offshore from Isla San Lorenzo, Lima, Peru; July 12, 2017.) © Brian Sullivan

“Fuegian Storm-Petrel”, O. o. chilensis—likely, based on location and time of year—showing no distinct stripe on the underwing coverts, and thus indistinguishable from typical “Wilson’s”, O. o. oceanicus. (Offshore from San Antonio, Chile; June 20, 2015.) © Pablo Andrés Cáceres Contreras

Geographical probability is the most useful clue for distinguishing “Fuegian” from typical “Wilson’s”. However, “Wilson’s” occurs as a migrant throughout “Fuegian’s” latitudinal range (at least during March, April, October, and November—and presumably in small numbers throughout the year), so geography can be strongly suggestive, but is rarely definitive for the identification of any particular individual.

Notes

Polytypic species consisting of two or three recognized subspecies that represent two distinct forms: “Wilson’s Storm-Petrel” (oceanicus and exasperatus, which are often merged) and “Fuegian Storm-Petrel” (chilensis).

In addition, the localized Pincoya Storm-Petrel (pincoyae) of south-central Chile has been recognized as a separate species, but could plausibly be reclassified as a morph or subspecies of “Fuegian”, or alternatively as a related but separate distinct form of Wilson’s.

Additional Photos of Wilson’s Storm-Petrel

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, showing pale bars on upperwing coverts. (Offshore from Poor Knights Islands, New Zealand; October 25, 2021.) © Scott Brooks

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; May 31, 2020.) © Trevor Sleight

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from South West Rocks, New South Wales, Australia; April 3, 2021.) © Jodi Webber

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand; November 15, 2018.) © Lars Petersson

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from Southport, Queensland, Australia; April 28, 2019.) © Deborah Metters

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from Eaglehawk Neck, Tasmania, Australia; October 31, 2019.) © Michael Fuhrer

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, with long legs dangling. (Offshore from Chatham, Massachusetts; July 21, 2018.) © Peter Flood

Wilson’s Storm-Petrels, in typical feeding formation, pattering their feet in the water. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 13, 2011.) © Holly Merker

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel, with long legs dangling to patter its feet in the water while foraging. (Offshore from South West Rocks, New South Wales, Australia; April 3, 2021.) © Jodi Webber

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from Poor Knights Islands, New Zealand; October 25, 2021.) © Aaron Skelton

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; August 25, 2017.) © Tom Benson

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from South West Rocks, New South Wales, Australia; April 3, 2021.) © Jodi Webber

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Offshore from Southport, Queensland, Australia; April 28, 2019.) © Deborah Metters

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Bay of Isles, South Georgia; March 14, 2012.) © Brian Gratwicke

Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. (Hop Island, Prydz Bay, Antarctica; January 1990.) © Collin Miskelly

References

Alderfer, J., and J.L. Dunn. 2014. National Geographic Complete Birds of North America (Second Edition). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

BirdLife International. 2018. Oceanites oceanicus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22698436A132646007. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22698436A132646007.en. (Accessed November 15, 2021.)

Brazil, M. 2009. Birds of East Asia. Princeton University Press.

de la Peña, M.R., and M. Rumboll. 1998. Birds of Southern South America and Antarctica. Princeton University Press.

eBird. 2021. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, N.Y. http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed November 15, 2021.)

ffrench, R. 2012. A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago (Third Edition). Cornell University Press.

Garcia-del-Rey, E. 2011. Field Guide to the Birds of Macaronesia: Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Cape Verde. Lynx Editions, Barcelona.

Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Howell, S.N.G. 2012. Petrels, Albatrosses & Storm-Petrels of North America. Princeton University Press.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

Howell, S.N.G., and K. Zufelt. 2019. Oceanic Birds of the World. Princeton University Press.

Kirwan, G.M., A. Levesque, M. Oberle, and C.J. Sharpe. 2019. Birds of the West Indies. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Martínez Piña, D.E., and G.E. González Cifuentes. 2021. Field Guide to the Birds of Chile. Princeton University Press.

McMullan, M., and T. Donegan. 2014, Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia (Second Edition). Fundación Proaves de Colombia, Bogotá.

Mullarney, K., L. Svensson, D. Zetterström, and P.J. Grant. 1999. Birds of Europe. Princeton University Press.

Onley, D., and P. Scofield. 2007. Albatrosses, Petrels & Shearwaters of the World. Princeton University Press.

Pizzey, G., and F. Knight. 2012. The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. HarperCollins, New York.

Pratt, H.D., P.L. Bruner, and D.G. Berrett. 1987. A Field Guide to the Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press.

Pyle, R.L., and P. Pyle. 2017. The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status. Version 2 (January 1, 2017). http://hbs.bishopmuseum.org/birds/rlp-monograph/. B.P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Ridgely, R.S., and P.J. Greenfield. 2001. The Birds of Ecuador, Volume II: Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

Ridgely, R.S., and J.A. Gwynne. 1989. A Guide to the Birds of Panama (Second Edition). Princeton University Press.

Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker. 2007. Birds of Peru. Princeton University Press.

Seabirding of Japan. 2021. Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. http://seabirding-japan.com/wilsons-storm-petrel/. (Accessed November 15, 2021.)

Sibley, D.A. 2014. The Sibley Guide to Birds (Second Edition). Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Sinclair, I., P. Hockey, W. Tarboton, and P. Ryan. 2011. Birds of Southern Africa (Fourth Edition). Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd. Cape Town, South Africa.

Southey, I. 2013. Wilson’s storm petrel. In New Zealand Birds Online (Miskelly, C.M., ed.). http://www.nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/wilsons-storm-petrel. (Accessed November 15, 2021.)

van Perlo, B. 2002. Birds of Western and Central Africa. Princeton University Press.

van Perlo, B. 2009. A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. Oxford University Press.

Wikiaves. 2021. Alma-de-mestre. https://www.wikiaves.com.br/wiki/alma-de-mestre. (Accessed November 15, 2021.)

Xeno-Canto. 2021. Wilson’s Storm-Petrel – Oceanites oceanicus. https://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Oceanites-oceanicus. (Accessed November 15, 2021.)