If you go down to the River Esk today you may be in for a visual surprise. At the base of an alder, crack willow or poplar on the river bank there may be a startling carpet of intense purple flowers with the exotic appearance of an orchid, but stemless, emerging straight out of the ground. The plant is Lathraea clandestina L., commonly known as the purple toothwort.

Lathraea clandestina is a flowering plant in the broomrape family Orobanchaceae. The genus name Lathraea derives from the Greek lathraios, or hidden; the specific epithet clandestina meaning kept secret or done secretively, refers to the fact that for nine or ten months of the year the plant is almost entirely underground, only revealing the massed creamy-white tips of the flowering shoots in February and disappearing again in May after setting seed. The flowers open en masse at ground level and are a very striking purple, often forming a dense mat of colour.

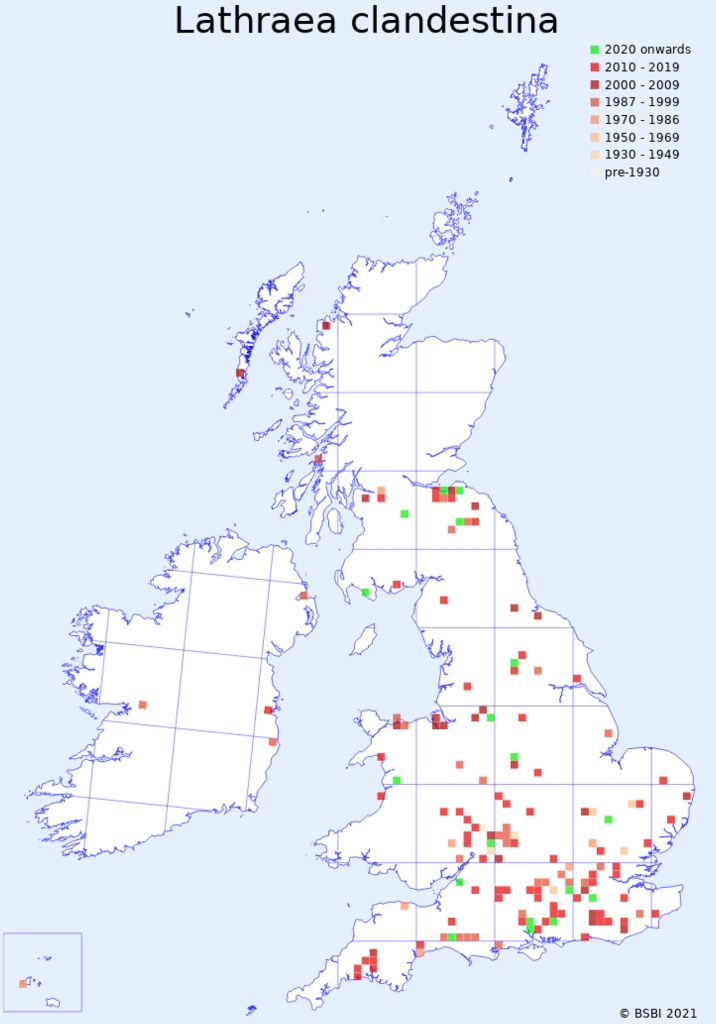

It is a neophyte, introduced to the British Isles from somewhere in its European haunts in 1888, and then first reported in the wild in 1908 at Coe Fen (Cambridgeshire), probably from deliberately planted material.

Description

Lathraea clandestina is a perennial holoparasite, meaning that it is totally dependent on theft of resources from other plant species, and cannot produce any photosynthate of its own. Except when flowering, the shoot system is entirely subterranean for nine or ten months of the year. The stems and leaves are white or off white in colour, sometimes pale pink, and entirely lacking chlorophyll. The leaves are strongly reduced to fleshy, succulent, scales, alternate below becoming opposite and somewhat clasping towards the shoot tips where the leaves are opposite and decussate.

Underground, lateral shoots arise from the leaf axils They are fragile, breaking easily. Supported by the surrounding soil they have little need for lignified supporting tissues. The root is bright yellow, and forms haustoria on contact with roots of other species.

The flowering shoot tips bear flowers on crowded short pedicels, and the deep purple flower buds arise from the axils of leaves that are closely imbricated in way that recalls the shoots of Honkenya peploides. The flowers emerge at ground surface level, without any aerial stem and are therefore potentially vulnerable to nectar robbing by birds, or insects such as ants. The first visible signs are the white tips of crowded groups of leaves, followed by the purple calyces. The calyx consists of four parts fused into a tube, the triangular tips curved inwards so that they join together to form a closed protective cover for the developing corolla within. The strikingly purple flowers are perfect, the corolla tubular and hooded, about 40mm long, the ovary superior and the long style just exerted, revealing a single round stigma.

The four stamens are separate but the anthers are clustered together just behind the stigma, underneath the corolla hood. The corolla tube has a constriction about 1/3 of the distance from its base, and at that point a dense ring of white hairs fills the tube, so that the lower part of the corolla tube forms a protected container for the nectar, which can only be reached by a long-tongued insect. In addition to this mechanical defence against nectar robbing there is a chemical deterrent. The nectar is strongly alkaline, up to pH11, and ammoniacal in smell and taste, the ammonia produced by de-amination of amino acids. Prŷs Jones and Willmer (1992) report observing several instances of naïve passerine birds showing an interest in the flowers, followed by rapid recoil and vigorous beak-cleaning activity. Birds were not observed to try again, once bitten twice shy. Bumblebee queens however seem to be immune to the effects of the ammoniacal nectar and appear to be the primary pollinators. Based on observations at Kew from 1955-2013, Atkinson and Atkison (2020) reported first flowering dates of 27 January to 27 April, with a mean of 19 March. The seeds develop from May to mid-June. They are very large, about 5mm diameter and are ejected forcibly over distance of as much as 8m. Lathraea clandestina propagates both sexually by seed and asexually by fragmentation of its extensive underground branching system, perhaps the commonest mode given its preference for unstable, erosion-prone, sandy riverbanks.

The first task of the root of a germinating seedling is to seek out the root of a suitable host on which to attach, and on finding one it forms an organ known as a haustorium that adheres to the root. Emerging from the haustorium, a sheet of tracheids, referred to as the transfer bridge, penetrate the host root deeply, entering and disrupting living cells en route, ignoring the phloem and making direct connections to the xylem (Těšitel, 2016), from which it draws large volumes of the sap. Xylem sap offers a meagre diet of sugars and other organic compounds that are only present in xylem in dilute solution. Lathraea is exceptional among Orobanchaceae in this respect, of having no connection to the phloem, which is richer in sugars.

A potential survival mode for an underground plant is to hook up with fungi, relying on them to provide nutrient resources in a form of symbiosis that frankly amounts to parasitism. Examples are the Dutchman’s pipe, Monotropa uniflora and Yellow bird’s nest, Hypopitys monotropa, both species in the Ericaceae that parasitise Basidiomycete fungi such as those in the family Russulaceae. However, no mycorrhizal associations are known for Lathraea clandestina. So far as is known it shuns the good life and lives as a purist xylem-feeder.

© Chris Jeffree

In most land plants, the power source driving the transpiration stream (the transport of water in the xylem), is solar-powered evaporation of water from the mesophyll cells, the rate of which is controlled by the stomata. Since its leaves are underground where the atmosphere in any airspaces is saturated, evapo-transpiration is almost impossible. Lathraea clandestina instead powers the extraction of water from its host by actively secreting water from specialised glands known as hydathodes on its underground leaves. The excess sap is pumped into the soil in quantities that can make the surrounding soil permanently wet. One implication of xylem-feeding is that the species avoids any need for biochemical compatibility with the living phloem tissue of a host, which restricts most phloem-feeding parasites to one or a very few closely related specific hosts.

Lathraea clandestina is mostly associated with various species of willow, alder or poplar that are common in riverine woodland, but is not very host specific. Atkinson and Atkinson (2020) compiled a list of 38 plant families which have been recorded as hosts, including ferns, native and exotic conifers, many species of broad-leaved trees, shrubs such as box, roses and honeysuckle and a variety of herbaceous flowering plants including nettle, violets, hogweed and grasses. Clearly almost any root will do. In parts of Europe that represent the core of its range, Lathraea can cause economic damage to crops, particularly to permanent crops such as grape vines.

There has long been speculation that Lathraea may be protocarnivorous, and that the specialised glands in the rhizome scales could be involved in the absorption of nutrients released from small organisms that become trapped and digested. Jollivet (1998) appeared to be persuaded that the plant trapped and digested small insects. However, in the opinion of Fay (2010) carnivory remains just that – mere speculation.

Distribution

In Britain, Lathraea clandestina is a neophyte, relatively recently introduced. It is native to western Europe, predominantly (the largest geographical area) in south western France and northern Spain, but with a disjunct area in Belgium and a fragmented distribution in western Italy. It is virtually absent from Ireland.

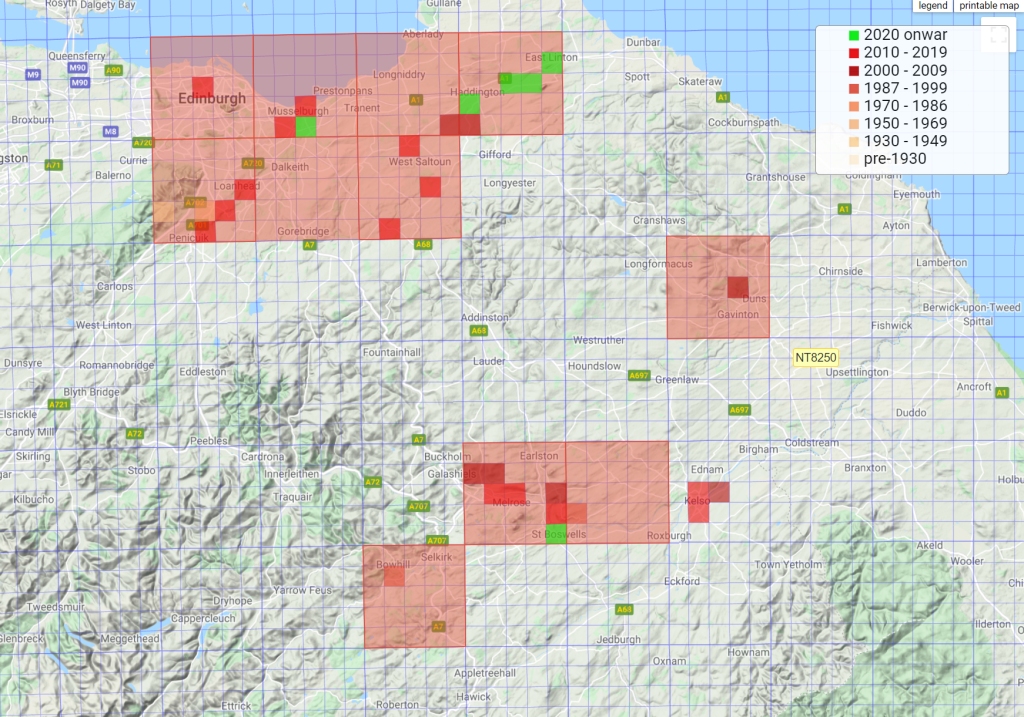

For the most part, the distribution in Great Britain consists of widely scattered locations, but in Lothian and the Borders it is common along watercourses, where plants growing on willow, alder and poplar roots become fragmented by riverbank erosion, the fragments depositing further downstream. We observed this process near Musselburgh, where a large and photogenic patch below the weir broke up when the river was in full flood and was dumped in a puddle, where three years later it is now well established.

© Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland

© Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland

Records of Lathraea clandestina follow the course of the River North Esk through Penicuik, Roslin Glen, Loanhead, and then beyond its confluence with the River South Esk to Newcraighall and Musselburgh, but there are no records along the South Esk, so it may be that the Esk populations consist of clones from the same, presumably planted, source somewhere south of Penicuik. There is another disjunct track further east along the River Tyne and its tributaries from Fala dam to Samuelston, through Haddington to East Linton and perhaps beyond, where as yet there are no records. A third track in our region begins along the Ettrick water near Bowhill, and then along the Tweed taking in Tweedbank, Gattonside, Bemerside, St Boswells and Kelso. Plenty of opportunities there for eagle-eyed botanists to fill the gaps in the record.

References

Atkinson MD and Atkinson E. (2020) Biological Flora of the British Isles: Lathraea clandestina. J Ecol. 108, 2145–2168. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13473

BSBI / BRC Online Atlas of the British and Irish Flora https://www.brc.ac.uk/plantatlas/plant/lathraea-clandestina

Fay MF. (2010) Lathraea clandestina, Orobanchaceae. Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 2010 vol. 26 (4): pp. 389– 397. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1467-8748.2009.01674.x

Jollivet P. (1998). Interrelationship between insects and plants. CRC Press, BocaRaton.

Prŷs-Jones OE and Willmer PG. (1992) The biology of alkaline nectar in the purple toothwort (Lathraea clandestina): ground level defences. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 45, 373-388.

Těšitel J. (2016). Functional biology of parasitic plants: A review. Plant Ecology and Evolution, 149, 5–20. https://doi.org/10.5091/plecevo.2016.1097

Chris Jeffree

This plant grows very close to where I live. I spotted it last year in April and started to try to find out what it was and gave up. Spotted it again this year and with the help of my son have found out what it is and have just come across this article. Now I am happy I know everything about the beautiful purple flowers hiding under the trees,great article.

LikeLike

Thanks for all the information. I had not known of the existence of this species and I have now seen it along the N Esk.

LikeLike