Recently we were recording the flora of the towns of Stevenston and Ardeer, by the Firth of Clyde in North Ayrshire. This part of Scotland is rich in industrial history. Coal-mining, iron-making and the manufacture of explosives all took place here, employing a huge work-force. Ardeer was where Alfred Nobel established the British Dynamite Factory in 1871; it became the world’s largest supplier of dynamite. Now, these activities have gone, leaving derelict land and dunes for plants to colonise.

We knew that a very special plant, the Isle of Man Cabbage, grows around here. We found it easily, in the dunes. It is a nationally scarce plant in risk of extinction, but abundant in these dunes. We were there in mid-May, and flowering had just begun.

Coincya monensis ssp. monensis. Note: basal rosette, red stems, about 25 cm tall. Photo: Chris Jeffree

It was first discovered over 300 years ago, on the Isle of Man (hence its name). It is not a spectacular plant and can easily be overlooked. Like many members of the cabbage family (Brassicaceae) it has a cluster of yellow flowers (each with four petals) held aloft on stiffish stems arising from a basal rosette of leaves. The stem is smooth and red, the leaves are much-divided and dark green. The population we were looking at was quite dispersed, and there were many individuals – perhaps a few hundred (I should have counted!).

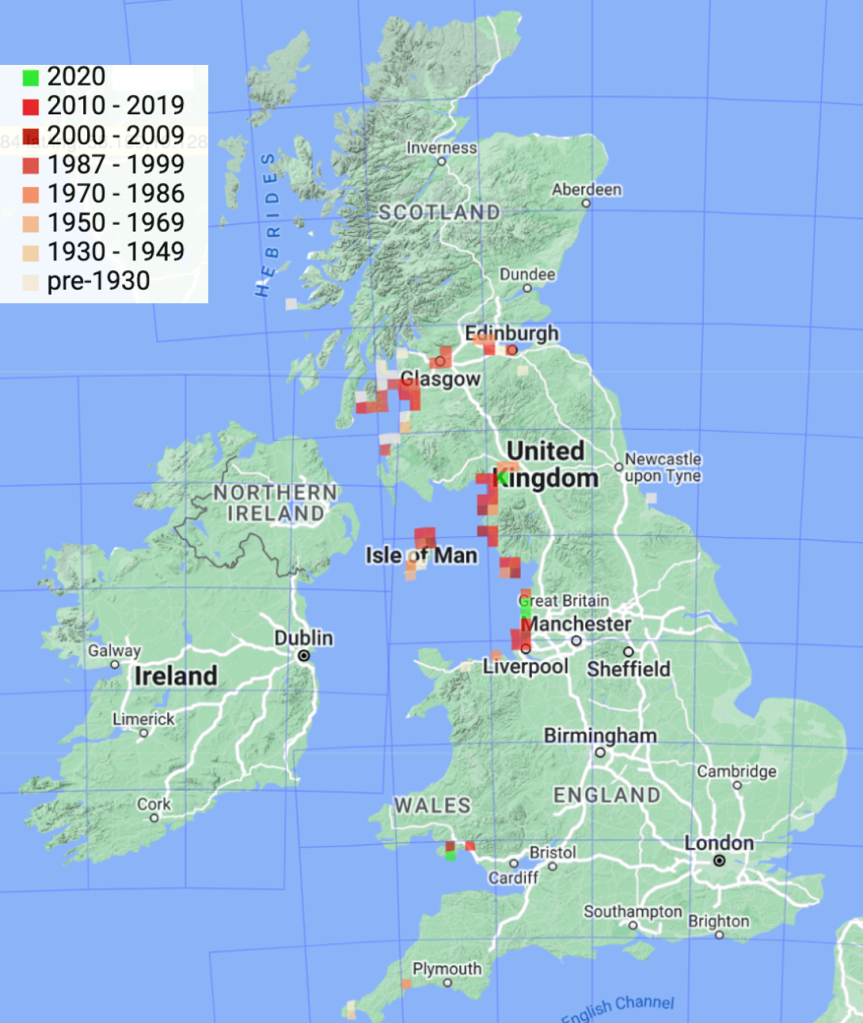

The windy and storm-battered dunes on the western shores of Britain are its preferred habitat. It is very fussy about where it will grow: the distribution map at the end of this article shows how rare it is. It co-exists with a broad range of dune species – we recorded about 40 cohabiting species at this one site. Marram Grass was dominant. Evidently the Cabbage cannot stand competition – it occurs in the barer patches. A few people have collected seeds for scientific study, summarised by Hipkin and Facey (2009). They note that the plant doesn’t grow inland – it is apparently killed by harsh winters; but here, near the sea, the winter temperatures are slightly higher.

It is described as an ‘endemic’ plant. Rich (2020) provides a list of 804 plants which are considered as endemic to the British Isles (meaning they occur only in the British Isles). I had not realised there were so many, I thought there might have been perhaps a dozen. But Rich’s article does not emphasise the distinction between an ‘endemic plant’ and an ‘endemic species’. Many of the plants in his list are sub-species or micro-species which reproduce asexually and occur as local populations. There are, for example, 230 endemic micro-species of the Dandelion (Taraxacum) and 260 of Hawkweed (Hieracium). Micro-species are strange organisms – they have lost the ability to reproduce sexually, and so all their offspring are genetically identical (clonal or very nearly so). This means they are at an evolutionary ‘dead end’ unable to adapt and therefore confined to a limited geographical range. Very few botanists can identify more than a few and thus, for recording purposes, they are often placed into coarse groups.

At Stevenston, Isle of Man Cabbage growing with Marram Grass on the dunes. Photo: Chris Jeffree

But Isle of Man Cabbage is not a micro-species. It is a subspecies, fully sexual, outbreeding and with insect pollination. There are two subspecies of Coincya monensis. The Isle of Man Cabbage is subspecies monensis. The other one, known as the Wallflower Cabbage is subspecies cheiranthos. Whereas ssp. monensis is endemic to Britain, ssp. cheiranthos is alien, a native of south-west Europe. It has even found its way to North America. In the BSBI Handbook for this plant family, Rich (1991) stresses how hard these subspecies are to tell apart. They do however differ in their chromosome count: for monensis 2n=24 whilst for cheiranthos 2n=48.

We are left wondering why some plants are rare whilst others are common, even when they share so many characters. When the ssp. cheiranthos reached North America it spread rapidly, and is often considered as ‘invasive’. In Europe it is widespread and it grows inland in the British Isles, whilst ssp. monensis is endemic to Britain and confined to dunes. Natural hybrids have not been recorded although hybridisation has been achieved in experimental conditions (Leadlay & Heywood 1990).

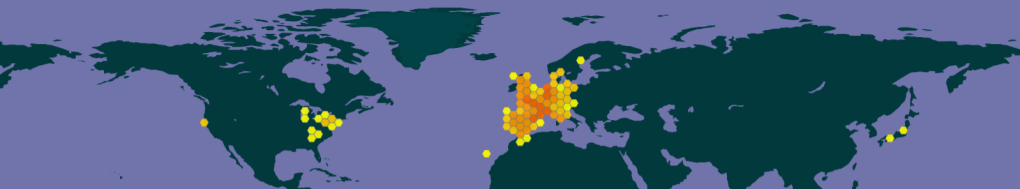

Distribution of the other subspecies, Coincya monensis ssp. cheiranthos: native of SW Europe and introduced into North America and Japan. From GBIF.

The Isle of Man Cabbage was once considered to be a species rather than a subspecies. This recalls the old question ‘what is a species?’. The issue was first raised by Darwin and has been the subject of many university essays. I was interested to see that the debate is still alive, and the species concept continues to be questioned and debated (Wang et al 2020).

Is the plant at risk of extinction? At Crosby, Merseyside, one site was excavated to provide sand for a coastal protection scheme at nearby Hightown. An attempt was made to translocate the population to a new site, but the success rate was poor (Smith & Lockwood 2012). Overall the species appears to be on a declining trend: the distribution map (below) shows only two newly-found locations and several locations where the plant hasn’t been seen for a long time. It may well become extinct.

What about the name? The genus Coincya commemorates the French botanist Auguste-Henri Cornut de la Fontaine de Coincy (1837 – 1903). The specific name comes from the Latin for the Isle of Man, which is Monapia. Confusingly, the name of the species has not always been Coincya monensis. Old names include Rhynchosinapis monensis, Hutera monensis and Brassica monensis. Also confusing for beginners: the cabbage family changed its name from Cruciferae to Brassicaceae relatively recently. We are fortunate that the highly memorable English name Isle of Man Cabbage has endured longer than the Latin.

Distribution of Coincya monensis ssp. monensis in the British Isles. Note: many records are ‘old’ but only two are 2020. Also, the strange absence from dunes on Ireland’s west coast. From BSBI.

Acknowlegement

I would like to thank the local botanists of the BSBI who guided our North Ayrshire plant hunt and made it so successful.

References

Hipkin CR Facey PD (2009) Biological Flora of the British Isles: Coincya monensis (L.) Greuter & Burdet ssp. monensis (Rhyncosinapis monensis (L.) Dandy ex A.R. Clapham) and ssp. cheiranthos (Vill.) Aedo, Leadley & Muñoz Garm. (Rhyncosinapis cheiranthos (Vill.) Dandy). Journal of Ecology 97, 1101-1116.

Leadlay EA & Heywood VH (1990) The biology and systematics of the genus Coincya Porta & Rigo ex Rouy (Cruciferae). Botanical Journal of the Linnaean Society, 102, 313–398.

Rich TCG (1991) Crucifers of Great Britain and Ireland. BSBI, London.

Smith PH & Lockwood PA (2012) Translocating Isle of Man cabbage Coincya monensis ssp. monensis in the sand-dunes of the Sefton coast, Merseyside, UK. Conservation Evidence, 9, 67-71

Wang X et al. (2020) Genes and speciation: is it time to abandon the biological species concept? National Science Review 7: 1387–1397.

©John Grace