We have seen Red Bartsia many times recently. It’s a hemi-parasitic plant that attaches itself to the roots of neighbouring species and draws water, minerals and organic compounds from its host. It does however have its own chlorophyll, and is capable of surviving and growing without a host, hence it’s a ‘hemi-parasite‘ as opposed to a strictly parasitic plant.

Odontites vernus with its old name Euphrasia odontites, by Jan Kops, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Jan Kopps (1765-1849) wrote and illustrated the 28 volumes of Flora Batava, the first inventory of wild plants in the Netherlands.

It is reckoned to be a native species, and an annual. In Gerard’s Herbal of 1597 it has a different name, Crataeogonon euphrosine ‘Eye-bright Cow-wheat’, but from the drawing it is clearly Odontites vernus. Gerard obviously knew this plant from personal experience: he reports finding it “upon Hampstead Heath near London, among the Juniper bushes and bilberry bushes in all the parts of the said heath, and in every part of England where I have travelled”. So, it appears to have been widespread in his time. It still is widespread, but less common in the north and missing from the extreme north and on mountains.

One typical habitat of Odontites vernus: grassland with clover. Bull Island, Dublin. Image: ©Chris Jeffree.

Clapham et al. (1987) say it is “common in cultivated and uncultivated fields and waste places throughout the British Isles” but this assessment may be out-of-date (rather few wild plants are common in cultivated fields these days). Averis (2013) is more fulsome: “dry to damp, more or less neutral soils, in short grassland and on bare or stony ground by roads and arable fields and coasts”. We found it recently at Holyrood Park in Edinburgh, on derelict land at the edge of a car parks in Livingston, and at an old rubbish tip near the coast at Lendalfoot in Ayrshire.

Worldwide, parasitic and hemi-parasitic plants make up as much as 1% of all Angiosperms and they have aroused considerable scientific curiosity. How do they work?

The range of plant form seen on derelict land. Left: vigorous plant (30 cm tall) from a sward of grass and clover; right: depauperate plant (11 cm) growing 50 cm away from any possible host plant (starved). Note (left hand image) that the branches and leaves are arranged along the stem in pairs, with each pair at right angles to the pair above or below (‘decussate’). These plants were found growing at an old rubbish tip near Bennane Head, South Ayrshire, 12 August 2023. Images: John Grace.

Parasitic and hemi-parasitic plants connect with their host’s tissue by root-like structures called haustoria, and it is through this intimate connection that water and nutrients are drawn. Many hemi-parasites have high transpiration rates, thus creating a ‘river’ for transport of dissolved materials. For a useful review, see Těšitel et al. (2010).

Early research by a group from Queen’s University in Belfast used 14C-labelled carbon to trace the path of organic compounds from selected host plants (Barley or Clover) to Red Bartsia. As a tracker for mineral nutrients, they used 32P phosphate mixed in with their John Innes potting compost. Then they decapitated the shoots of Red Bartsia to see whether the labels had been translocated. They had. On the case of Barley, 53 % of the 14C label applied to Barley was recovered in the sap of Red Bartsia as sugars, 12 % as organic acids and 35 % was in the 19 different amino acids. For the full story, you may want view their work here. The paper includes (in the discussion) a brief review of previous work which extends back into the previous century.

Detail of flowering spikes. The toothed leaves are in opposite pairs, usually red-pigmented. The flowers are two-lipped: the upper lip is two-lobed, the lower lip is three-lobed. They.are pollinated by bees and wasps. Images: ©Chris Jeffree.

In my trusty old Flora (Clapham et al. 1987), Odontites and the related parasitic plants (Rhinanthus, Melampyrum, Euphrasia) belong to the Family Scrophulariaceae (the Family of Foxgloves and Speedwells). But now they have been moved to the Orobanchaceae. Stace (2019) explains that “The long-expressed opinion that the semi-parasitic Scrophulariaceae …. should be placed with the totally parasitic Orobanchaceae has been confirmed by molecular studies”. Why do these revisions occur, and who decides?

In older Floras the Families and their genera more or less followed Bentham and Hooker’s work, published between 1862 and 1883. But in the 1990s there came a revolution, as the tools of molecular biology were brought to bear on plant taxonomy. It was realised that genetic similarity rather than structural similarity would be a more reliable basis for a new taxonomy that truly reflected evolution. Darwin in 1859 and Haekel in 1866 used the metaphor “tree of life” to conceptualise evolution, and a Century later the statistical techniques of numerical taxonomy (pioneered in 1963 by the Americans Sokal and Sneath) enabled organisms to be grouped together in a tree-like structure. Today, specialist laboratories are able to take plant material from the field or herbarium and using very clever technologies they can reveal details of the genome and deduce how related one species really is to another. Often, the ‘old taxonomy’ is confirmed but sometimes it is refuted. The strength of any proposed piece of ‘new taxonomy’ is evaluated by a group of scientists known as the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG), who met in 1998, 2003, 2009 and 2016 with the grand aim of making taxonomy reflect evolutionary relatedness. They make the recommendations, others follow.

O. vernus with seed capsules. Image: ©Chris Jeffree.

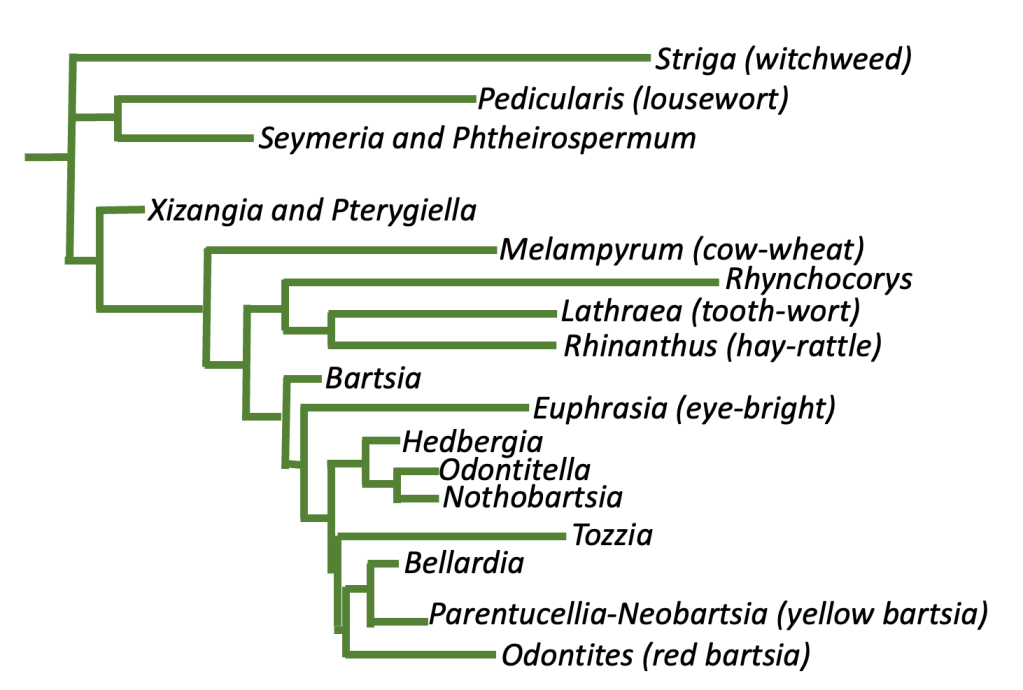

For people who write floras, organise herbarium specimens or engage in field botany, this is of course quite inconvenient (revolutions are always inconvenient). Please look at the highly readable essay about this from the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, by Janette Latta here. With phylogeny in mind, I decided to find recent work on the changing phylogenetic status of Odontites and its relatives. I found a useful paper from a European research group (Pinto-Carrasco et al. 2017). The research involves extracting and amplifying the DNA from a huge sample of species, and then testing the similarity in the DNA sequences between all pairs of genera. Finally, the similarities can be visualised as a branch of a tree, wherein similar genera are twigs that are close together (see the image below). I was deeply puzzled at first as Odontites and Bartsia are far apart, even though Odontites is called ‘Red Bartsia’. Surprises occur in this sort of analysis. Odontites is more related to Euphrasia (the Eye-Brights) than it is to Bartsia. Comfortingly, Red Bartsia clusters near to Yellow Bartsia (Parentucellia) but neither should have been given the English name Bartsia!

I found that an earlier name for Odontites vernus was Euphrasia odontites (the name Linnaeus used), so the old taxonomists using structural criteria alone were nearly right (O. vernus is more like a Euphrasia than a Bartsia).

Cladogram showing the place of Odontites in the phylogeny of the Orobanchaceae. Simplified and redrawn from Pinto-Carrasco et al. (2017), with examples of English names added where possible. Note the location of Bartsia, far from Odontites (in the British flora we have only one ‘true’ Bartsia, the rare Alpine Bartsia, B. alpina)

The etymology of the word ‘Odontites’ is interesting. It comes from the Greek, meaning ‘tooth-related’. Pliny the Elder says it was used to treat toothaches. One might expect the same properties in the related tooth-wort genus Lathraea. You may like to revisit our blogs on two species of tooth-worts here and here.

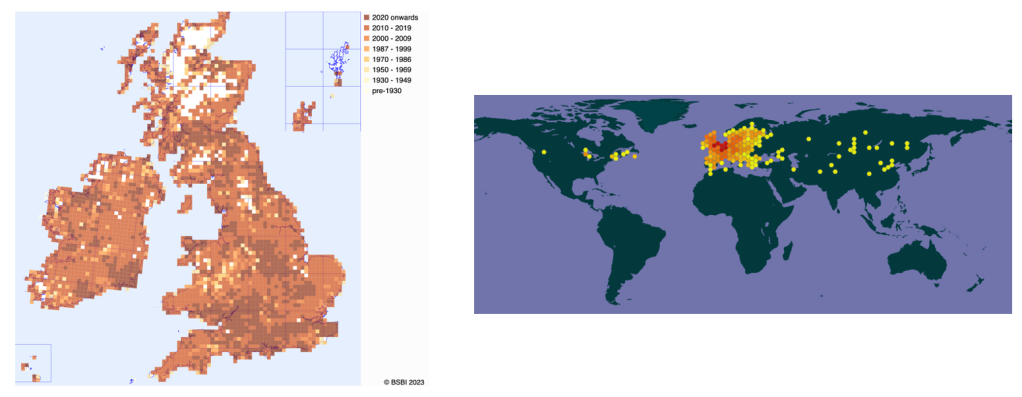

Odontites vernus: British/Irish distribution (from BSBI/Maps) and global distribution (from GIF).

The British and Irish map shows a widespread distribution that includes coastal habitats and salt-marshes, and land rising to higher elevations (595 metres at Ben Lawers in Perthshire). According to the BSBI Plant Atlas 2020 the distribution of this species has not altered significantly since the 1960s. Globally, it has its headquarters in Europe but it is naturalised widely in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The Red Bartsia bee, Melitta tricincta, a southern species, is apparently entirely dependent on the pollen of Red Bartsia (see some images here). The larva of the rare Dipteran Phytomyza tenella may also depend on Red Bartisa, feeding on its seeds.

It seems that the life style of Red Bartsia is similar to that of Hay Rattle, and the effect of its parasitism on grass and clover (keeping them in check) is useful if you want to create a patch of ’wildlife meadow’ in your garden. It will weaken its vigorously-growing hosts and that may favour smaller species and thus increase biodiversity. It isn’t as pretty as Hay Rattle but you can purchase the seeds and it probably does the job. I might try both together. I wonder, will they infect each other?

References

Averis B (2013) Plants and Habitats: An Introduction to Common Plants and Their Habitats in Britain and Ireland. http://www.benandalisonaveris.co.uk/publications/

Clapham AR et al. (1987). Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge.

Govier RN et al. (1967) Hemiparasitic nutrition in angiosperms: I. The transfer of organic compounds from host to Odontites verna (Bell.) Dum. (Scrophulariaceae). New Phytologist, 66, 285–297. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1967.tb06006.x

Latta J (2008) Changing to APG II :: Theory Put Into Practice. Sibbaldia: The International Journal of Botanic Garden Horticulture 6, 133–153. https://doi.org/10.24823/Sibbaldia.2008.39

Pinto-Carrasco D et al. (2017) Unravelling the phylogeny of the root-hemiparasitic genus Odonites: evidence for five main lineages. Taxon 66, 886-908. https://doi.org/10.12705/664.6

Stroh PA et al. (2023) BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020.

Těšitel J et al. (2010). Interactions between hemiparasitic plants and their hosts: the importance of organic carbon transfer. Plant Signal Behaviour 9, 1072-6. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.9.12563.

©John Grace