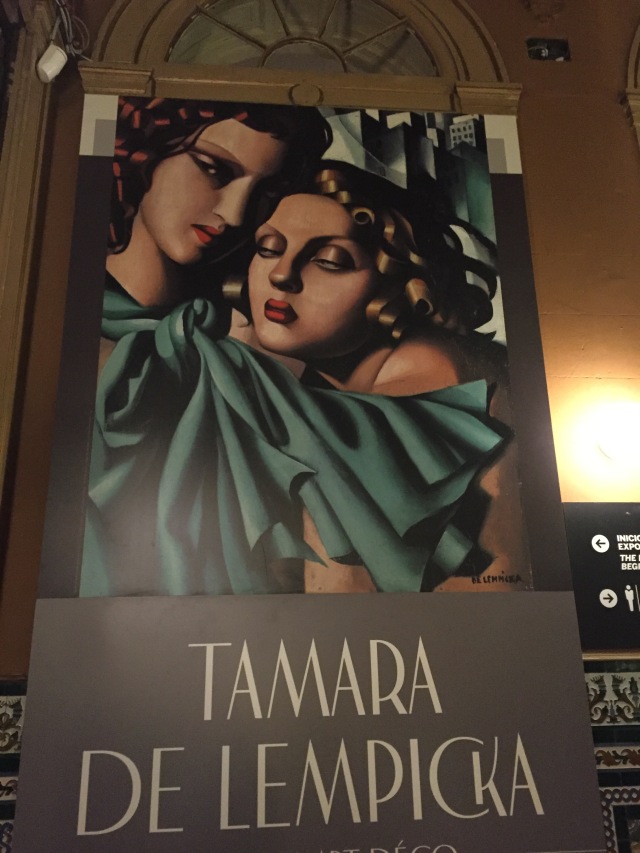

I was lucky enough to be in Madrid this week to see an exhibition that my Spanish sister-in-law Ana told me about: Tamara de Lempicka – Reina del Art Deco (Queen of Art Deco) in the Palacio de Gaviria. It’s a very well-composed exhibition which is set in a gorgeous old palace just off the Gran Via. The interior of the palace has a lovely shabbiness to it as though it has just been opened up after many years and hasn’t been refurbished. It’s dark and mysterious and the exhibition winds around numerous grand salons and corridors. Each room has a painted ceiling and there are large mirrors and moulded columns and cornices.

The faded glamour of the Palacio de Gaviria.

Art Deco – the total style.

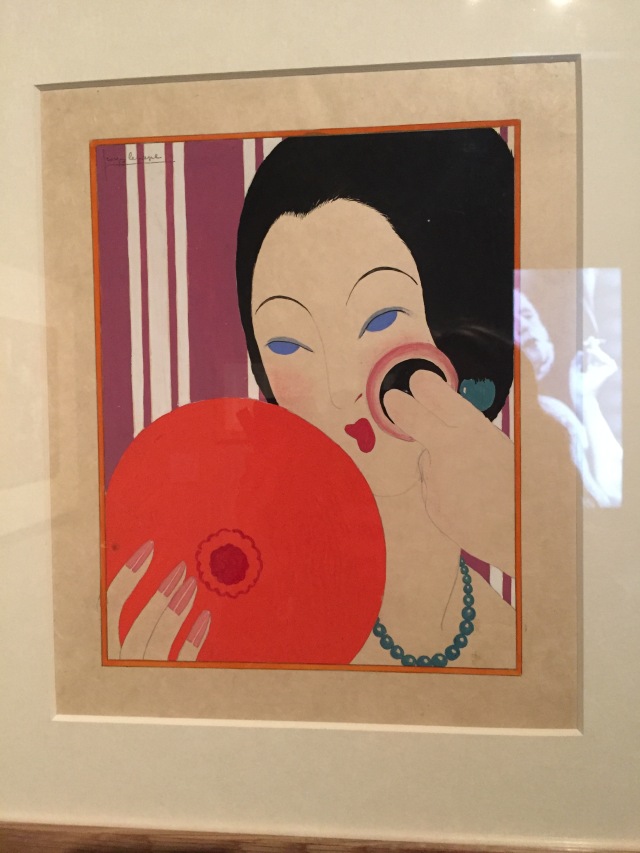

The paintings and drawings are shown along with huge photographs of the artist as well as lots of pieces of decorative design dated from around the period of the Paris 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (which gave its name to the Art Deco style), in which the artist participated. It was a very exciting exhibition for this reason: first of all you walk up an impressive sweeping staircase, with murals all around and chandeliers, then along a dimly lit corridor with rippled coloured glass panels on either side. The interior blends nineteenth century medieval and twentieth century styles – there’s even a bit of rococo. You then enter a screening room through a velvet curtain and watch a film narrated by the curator of the exhibition, which provides an overview of the artist’s life and work. The first exhibit that you encounter is a 1920s lacquered panel depicting Josephine Baker (an entertainer whose iconic image was used on all kinds of decorative and consumable objects) and other art deco pieces of furniture, screens, vases etc. dated from the period of the Paris exhibition. Tamara’s art, and she herself, is viewed within this context of art deco as a total style. Art Deco is sometimes described as an applied style or decoration which provided a veneer of modernity and glamour to everyday life.

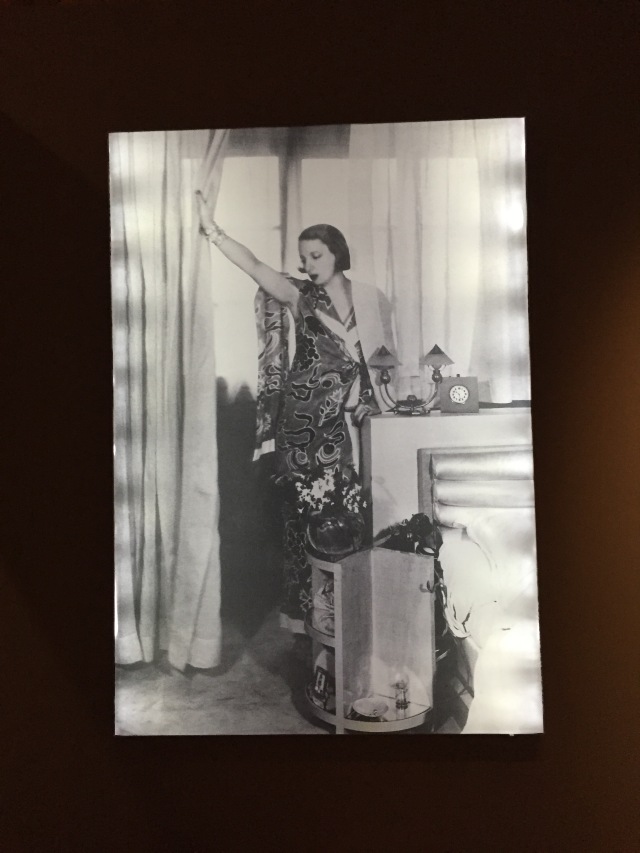

Magazine glamour shot of Tamara de Lempicka.

Although art is generally visually suggestive of the time in which it was created – one can normally see connections between the style of the art and what was happening in design in a given period – Tamara’s work was problematic for some critics because it seemed to be so obviously immersed in the style of the period. It wasn’t taken seriously – it probably seemed in itself to be decorative and sheer, highly stylised, composed of clean lines and colours and smooth surfaces. It was difficult for women to be taken seriously as artists anyway – they were encouraged to work as dress designers or interior decorators rather than artists. For this reason, although Tamara loved fashion design, she doggedly refused to involve herself in any of these prescribed female-orientated career directions. In her paintings, volumes / bodies are represented in a mechanistic way, like the streamlined objects of industrial design in which the joints and rivets are invisible. It is almost impossible to read the process of the art work as the paint is blended so finely that skin, lips, eyes and hair have an airbrushed quality like a photograph or a work of graphic illustration. Figures are given a monumental, statuesque quality. The exhibition contextualises this approach by showing the work alongside cover art for vogue and fashion illustrations of the period. However, the artist studied the old masters and was an admirer of renaissance art in which a perfection of light and surface was achieved and she worked to create this illusionary quality that dared the viewer to believe that it was painted at all.

The Young Girls (1928 / 1930)

The Blue Scarf (1930)

Context

A big surprise of the exhibition was the many items of fashion design on display; iconic 1930s shoes by Salvatore Ferragamo, a dress by Elsa Schiaparelli, purses and hats. Contemporary 1930s pathe films of the artist-star were played alongside these exhibits to show the way her work was consumed and interpreted along with her own image and lifestyle. This is similar perhaps to the way in which Dali’s identity and public persona were so integrated with his creative output, assisted by modern communication technologies. Tamara appears to have been a natural performer – the films show her choreographed movements, the tilt of her head, the way she used a cigarette as an accessory to her performance, in the same way that Marlene Dietrich did. Tamara is described as decadent and having lived a debauched lifestyle. She was an aristocratic exile from Moscow who fled to Paris in 1918 and struggled to provide for her daughter and husband (who couldn’t / wouldn’t work) and she used her talent to regain her status and live again in the glamorous and indulgent fashion to which she had been accustomed before the revolution. She didn’t fit into the unconventional and more socialist way of thinking that she encountered in the artistic cafes of Paris but she was a talented person who fought to preserve her individuality.

Not dressed-up in this scene but with perfect hair and dramatic make-up: Tamara painting her husband’s portrait (1930).

Her glamorous and uncompromising studio-apartment designed by Robert Mallet-Stevens (ca. 1928 – ), was featured in magazines.

Salvatore Ferragamo shoes

More contemporary context provided in the exhibition: maybe this is what her patrons were wearing in the 1930s.

Vogue cover (not by de Lempicka)

Fashion illustration by Tamara de Lempicka

Tamara de Lempicka in her Mallet-Stevens designed studio / apartment.

Self-Portrait

Artist – Star

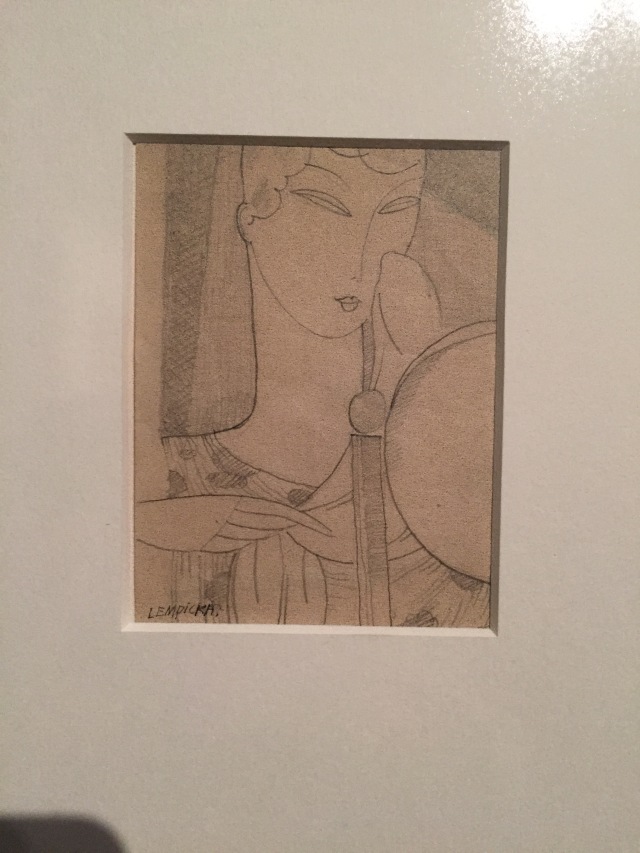

Her biographer (Laura Claridge) struggled to tell an accurate version of her story, although she had access to the author’s diaries, letters and interview material, because the artist had fabricated many aspects of it (Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence, 2000). It was clear from the start that Tamara was the author of her own life and history, controlling the version of events as they would be portrayed to the public as audience, just as modern performers were doing (although Hollywood producers and film studios normally controlled the story of their stars – Tamara was very much in charge of her version of events). Her art also has this detached and impersonal quality – there is little sense of the movement of the author’s brush across the canvas and she wanted to create this appearance of perfection in her art. However, the clouded grey eyes which she sometimes painted on otherwise glamorously portrayed female figures in some of her paintings was apparently a tribute to her mother who had developed blindness – this provided a small window into the vulnerability and sensibility of the artist. I wonder did Tamara worry that this would happen to her too? Her drawings seem more personal than her paintings and you can get a sense of her dedication in the neatness of her tiny pencil strokes and the care she took with shading, and the abstract, stylised suggestion of form.

Disciplined / Decadent

Tamara was supposedly decadent, self-indulgent and caught up in a fast-moving lifestyle of distraction and fantasy. However, her work suggests enormous discipline and dedication. She studied the work of great artists, developing her skills by learning from works of art in Paris, Florence, Madrid. A painting of a corner of a hotel room which is highly finished and detailed shows that she took the time to work on her art as she travelled. All of her work had a very polished quality which takes time and discipline to achieve. It makes me think that much of her public persona was orchestrated to present this image of glamour and modernity, which was only as real – but also as perfect – as a film depicted on a cinema screen, creating an aspirational and iconic figure in order to sell her art and ensure that she was always relevant. Many impoverished aristocratic exiles had resorted to working as fashion models in Paris at the time that Tamara was beginning her career. She moved in perfect synchronicity with the cinematic glamour of the period, presenting herself as this artist-star. Photographs of her supposedly engaged in painting are theatrically staged, showing her dressed like a film star, complete with furs and elaborate jewellery, similar to the way in which film stars were portrayed in promotional films and magazine articles. It seems impossible that a person could invest so much time in her appearance and produce such rigorously painted images. Like many women, she seemed to be able to do it all – and probably had a lot of pride in her appearance, wanting to reinforce the idea of her aristocratic origins. Overall, she communicated the idea of an ice-cool ambition – see her painting Self-Portrait: Tamara in a Green Bugatti, 1929.

Autoportrait: Tamara in a Green Bugatti (1929) – not featured in the Exhibition (maybe this is one of the paintings Madonna – a big fan of Lempicka – owns?)

Unlike many works of art which are far more revealing when viewed in real life, Tamara’s paintings don’t reveal much more in reality than they do as digital reproductions. This seems to reflect an aspect of the new technology of the time: they were produced in the machine age and her work reflected the technological modernity of that era, and the new pervasiveness of visual art in the environment of everyday life.

(Tamara de Lempicka was born in Warsaw in about 1898 and died in 1980).