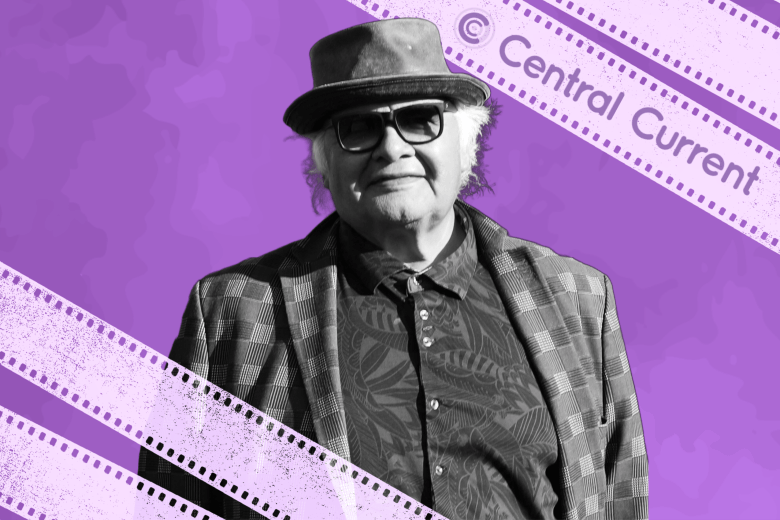

George Harrison. Forest Whitaker. Johnny Depp. Each of these elite entertainers collaborated with Cayuga actor Gary Farmer from the Six Nations of Grand River. Though he was born right across the border in the neighboring Canadian province of Ontario, Farmer’s upbringing was firmly rooted in Central and Western New York.

Farmer grew up in Buffalo, briefly attended Syracuse University and spent a decade performing theater in Toronto before ultimately setting off to forge an unforgettable Hollywood career that helped scores of ambitious Native actors follow in his footsteps.

His name is credited on many groundbreaking and culturally significant cinematic projects that deeply touched communities like his own, turning him into an instantly recognizable figure in the annals of Indigenous film history.

Appearances in the 1988 road-trip film “Powwow Highway,” “Dead Man,” a 1995 Western drama, and “Smoke Signals,” a 1998 indie listed in the National Film Registry, stand out as some of his most memorable performances that earned him a following throughout Indian Country.

More recently, however, his supporting role as the comedic stoner Uncle Brownie in the two-time Peabody Award-winning “Reservation Dogs” streaming series has brought him continued fame and praise. His clout as a notable Native celebrity has let him leverage his star power to prioritize undertold stories, both in and out of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

Last June, Farmer lended his voiceover abilities to bring Tom Longboat, an Onondaga long-distance runner, to life through Onondaga screenwriter Jessie Anthony’s short film, part of Historica Canada’s “Heritage Minutes” collection.

A residential school survivor who escaped from the Mohawk Institute Residential School, more infamously known as the “Mush Hole,” Longboat became a world-renowned marathon champion, the first Indigenous competitor to win the Boston Marathon, setting a new record in the process, back in 1907.

At the height of his athletic career, the Onondaga runner was assigned as a dispatch after deciding to enlist in the Canadian Armed Forces, where he ran messages and orders to units in France during World War I. Inducted posthumously into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1955, his legacy is still remembered each June 4th on Tom Longboat Day in Ontario.

Farmer’s enduring career, studded with several castings spanning five decades, wasn’t a success story overnight. He fought for his dreams, a trailblazer at a time when Indigenous faces and voices weren’t prominently featured in film and television.

His passion for the arts has always surpassed the silver screen. As a staunch advocate for advancing media representation, Farmer was one of the founders behind the Aboriginal Voices Radio Network and publisher of the Aboriginal Voices, a magazine focused on Indigenous artists in Canada.

Farmer connected with Central Current for an in-depth discussion about his recent trip to the Seneca Nation; the looming third season launches of “Reservation Dogs” on Hulu and “Resident Alien” on Peacock; recent Canadian wildfires; an upcoming tour of his band and Indigenous media representation in Hollywood and beyond.

Editor’s note: This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What motivated you to visit the Silver Creek School District last month?

Whenever I shoot this show, “Reservation Dogs,” I usually get a couple episodes off before I need to come back. I generally always go home from Tulsa, Oklahoma, to Niagara Falls, New York, and then cross the border and go 60 miles more to my home. Every year since I’ve been doing this series, that journey from Tulsa to Buffalo, you see Haudenosaunee all along that trail.

Those people have been there for at least 12,000 years, a long time that defies the theories that I was taught in grammar school in Buffalo. There’s a lot more information for these young [people] than there was for me. I talked to them about growing up in the industrial world, the past, the future and how the Seventh Generation is going to have to care for the planet because we’re all suffering from it now.

I grew up in cities, and I go back to them now. There’s too many people, you know, I can see it’s not working, so I tried to be real with them. I wanted them to be conscious of the future and how to look after the past and their future. That’s sort of what I discussed with them, besides my own little goofy career of 50 years.

You just wrapped up filming the third season for “Reservation Dogs” at midnight on Friday, so I’m curious to ask what this journey has been for you, playing such a prominent role in Uncle Brownie on that series?

I’ve known all the creative team for a long time, off and on; they’re a generation below me and have been making films for a while now. What’s nice about that project is its youth being able to express themselves — learning the trade — the production scenario of making content as it were — programming that could have positive impact or negative impact on society.

We haven’t had that opportunity much in the past. It’s all about controlling the narrative. Who owns the stations? Who owns the networks? What are their interests?

We’re still that far away from ownership, right, of our own networks, so we can determine when a series is done, what we want to say and do or communicate. I mean, that’s been a massive problem for probably over 2,000 communities in North America. We’ve had no electronic form of communication at all. I don’t know how we sustain, to tell you the truth, without any internal communication — no regular news.

It’s not that the Onondaga don’t get the newspapers, watch the television stations or listen to the radio stations in Syracuse, but do they have their own media, generating their own content, developing their own storytellers?

That’s not happening at a very large scale, if it is. The Native American Journalists Association is a small group. In the old days of the objective, there was information to be shared to help people make life choices. That information is not getting to us as Indigenous people. There are those threats for Native communities throughout America, since they’re not getting any information unless they search it out.

That’s challenging, and there’s a big effort in all of our communities to retain our languages and another reason for our media, so we could broadcast in our own language to help with the revitalization of these languages.

There’s still a lot of work to do in terms of media development, actually. I spent much of my life trying to get radio signals to Indigenous communities in Canada, and I always thought we needed to take a bigger angle at that.

Something that I’ve been following closely in recent days was the Canadian wildfire smoke pouring in, polluting our air and floating right across the border into Western and Central New York. You talk a lot about protecting the land and listening to the original inhabitants of these homelands that we occupy, so what’s your perspective on it all with your community of Six Nations of the Grand River bearing the brunt of it?

I think more and more as I get older, I wonder what if the settlers would have accepted the vibe that was here in America when they arrived, you know? Would we be in a different environmental state now, if we had just paid attention to the people that lived here on this side of the planet for centuries?

They’ve spent 2,000 years trying to change the story, but there’s so much knowledge among Indigenous Americans on how to sustain in this life forever. I mean, the language itself is the true study of nature based on observation over centuries of time. That exactly tells you how to live on the planet forever.

Wildfires are all climate change. It seems that the industrial nation, which started much before my birth, was controlled by all of these corporations that are leading us to certain death. I resent that now. I didn’t have a choice. I resented that the world was a bit different than when I started.

Ted Turner has as much land as Native America does. We don’t have much land. My people sustain on 25,000 square acres. It’s all been pretty well swiped away. If we do get recovered lands, they are generally toxic.

Our Haudenosaunee Confederacy had a system that was looking at 150 years and made decisions on that, not on two or four years. [Politicians] are not looking at 150 years from now, and that’s the problem with the system.

They’ll reclaim any resource to make as much profit as they can in those two or four years and move on. That’s been the history of politics in America, and it’s been allowed to go on like that. We’ve had to live by and suffer from it.

I wish choices were different. I wish we had more opportunity to make our choices in the past and now we’re all scrambling and working closer together because the Earth is nearly destroyed, with all the pollution and all the wrong decisions made for so long.

You had an opportunity to channel your inner Tom Longboat, an Onondaga who also grew up on the same reserve as you, by serving as his voice through Historica Canada’s “Heritage Minute.” How personal was that for you?

I was hired as the voiceover actor, but I grew up with Tom Longboat’s son who lived around the corner. My family owned, back in the early ‘70s, the only general gas station, tire fix-it shop in the center of the rez. I came home from Syracuse University after one year there and started working to help get them back on their feet with a new business.

That’s how I learned to know all of my own people, like Tom Longboat. It was my first time living there without any visitation of my cousins, but it was a wonderful period getting to know my community for real after 20 years.

The young filmmaker, Zoe Leigh Hopkins, who made “Run Woman Run,” is really about the spirit of Tom Longboat and a woman suffering from diabetic condition, which is a very normal situation in the Native community and elsewhere, of course.

It’s a wonderful film, entirely made on the Six Nations of the Grand River, about trying to bring more activity to life at a certain age when you’re facing diabetes from a feminine perspective, and is a tribute to Tom Longboat and his valuable life story.

Have there been any television or film castings that ever came close to personifying who truly you are, the real-life Gary Farmer?

Probably “Dead Man,” as Nobody. I felt that, I suppose in Buffalo. My father took us to the west side where the white folks were, with the Irish, Italian and Polish immigrants. I was probably one of two, maybe three or four, Native families; many of them were related to me. I always had to speak on behalf of Native people as a child in the Buffalo school system.

When I looked at the story of “Dead Man,” where his parents were married and both from tribes that didn’t necessarily get along, he was whisked off and taken too. It’s kind of like my life story, in a way.

As a child growing up in somewhat of a dysfunctional home where there was alcoholism, I reflected that again, in the movie, “Smoke Signals,” your favorite film of mine. People said, ‘Oh, how did you hit that child like it was nothing?”

I’d probably be a little too chunky to play Tom Longboat as a long distance runner, but that’s all you do as an actor, is apply your knowledge or understanding of the world and dig deep into these characters. Find what makes sense in terms of your own experience. Much of what I did sometime in my life, I find relations to it, in order to execute; it’s just the way it is.

I was just playing my father. It was nothing. I grew up with a father whose American Army training he got seemed to be reflected in our upbringing, you know? A lot of the work I’ve done, that’s all you have as an actor, is who you are.

Have you come to a consensus yet this far into your career on a favorite casting?

Nothing comes to mind. They’re all favorites. I appreciate the work I get. I try to make it work for them, for me. I got two wonderful projects right now, both with “Reservation Dogs,” which starts on Aug. 2, and “Resident Alien,” a sci-fi [series] also in its third season and just about to start as well.

The “Resident Alien” showrunner, Chris Sheridan, actually originally from and still living in Vermont, is a wonderful guy and did the show “Family Guy.” It’s just a marvelous job, and it’s so conscious. The leading character, Alan Tudyk, is just a brilliant performer, with a robust cast, and we all get along.

Much like “Reservation Dogs,” you know, they’re two separate shows and it’s great going back and forth between the both of them over the last three years. It all may come to an end this year, but it’s been a wonderful ride. I’ve been really gifted in my latter years to continue to still work, have my health and be able to shine for a few more years.

Another passion project of yours is being a musician. Talk to me about your band, Gary Farmer and the Troublemakers, how you formed it and your upcoming tour in July.

When I was 18 and left home, I guess to go to school, the only thing I seemed to pick up was harmonica. I took it with me; I started and just kept playing it. I was always large, so I could always survive being a doorman for whoever, you know, clubs in college.

I went to Geneseo Community College in Batavia, and we used to have this great big club called the Devil’s Rock. They used to have these beer blasts and for five bucks you could drink all the Genesee Cream Ale you can ingest. Back then, the J. Geils Band was big and I really took to Magic Dick and Whammer Jammer. I just never stopped and always said the harmonica has always been my friend.

Years later, I would travel around, always on the road. I would go find the local club with live music and worked my way to the stage. I learned that if you play good, you get to stay on stage. I’m just a real jammer. The instrument is really my heart, and love for music comes through on that harmonica, and I’m able to express myself. It was my voice for a long time ‘til I started singing, took me years to start, and that’s when that happened.

I sent Chris, the “Resident Alien” showrunner, my new album last year and he worked my band into an episode, so my Troublemakers make an appearance in the show. They picked up three of my original songs for the party scene, so that was an exciting moment for me and I got to bring my band together for television. They all enjoyed that.

My music has always been second to my acting career, but I’m feeling more like the frontman to bring an entertaining show with all of these talents together for communities this summer. I’m going to be doing a tour of Ontario July 12 to 29 for about 12 shows.

It keeps me young, playing music in a kind of a blues rock, rockabilly pop band. Performing original material along with three other singer songwriters, it’s a lot of work. That’s really why I have four singer songwriters. I’m getting older now, and I just like presenting the shows. I know how to be on stage musically. I’ve written songs and performed them. It’s hard performing live music, it really is.

That probably wouldn’t have happened even a few decades ago. There has been a recent cultural shift in Hollywood, allowing Indigenous creative minds to be set free and shape the content they’re involved with. What does it mean for you to be a Haudenosaunee artist, then versus now?

It was inevitable, I guess. It seemed like we couldn’t get out of the bedroom of rich white folks. That was the storyline based on them. Of course, I never fit into that storyline. There were a lot of actors before me that never claimed Native heritage. I mean, I can get away with not looking like a Native American in most people’s eyes. I got that all the time.

I felt a big part of that shift with my work in radio and magazines. I would remember the Canadians telling me, “You can’t put that in color.” I said why not, it’s going to be glossy and has to be in color because we’re beautiful. They’re like, “No, go black and white.” This is a magazine about lifting us up, about our stories.

I realized that as a young worker in the television industry in Canada. They were basically taking our stories and making television from them, but our writers weren’t getting any credit. The screenwriter would get 95 percent, but the original story gets 5 percent of the budget.

There was something wrong with that picture, and I was determined to change that. I worked hard at that for years. Sitting here at 70 years old, I’m really happy things have shifted. It’s a little late, from my perspective. I feel like we’re 20 years behind, but at least things are shaking and the Earth is telling us things, too.

I feel the young people were really aware of what I was telling them down at the Seneca Nation’s Cattaraugus Territory. I expect a large change from this coming generation. They’re so much smarter and more aware of the world around them than I was.

That world has been opened up to them. It’s taken me 70 years, but they’ve got it opened up at 20, so we’re gonna watch their careers unfold. Their [collective] consciousness that we’re giving them now is going to be tenfold from my generation.