Origins of the Rose Windows

The traditional rose window– the one with geometrical shapes spanning out from a centre, and made of stained glass – blew up in Gothic France. We’re talking about the 12th and 13th c. particularly in and around Paris.

From there, the stereotypical rose windows spread throughout the world, starting with neighbouring countries such as Italy, England and Spain.

Rose windows didn’t appear out of thin air; its ancestor may have been the oculus, a simple circular hole without glass or design, and is typically situated on the roof of ancient Roman religious buildings, such as the famous Pantheon, originally built in the 1st c. BC. The oculus was meant to let the air, light and rain travel through.

It could have been fashioned into other shapes but the circle was a favourite in houses of worship, as it’s a symbol of universal perfection across the world from as early as humans could visually express themselves. The ancient Chinese, ancient Egyptians, Sumerians, Hindus and Native Americans, all venerated the circle.

By the 9th century, oculi (plural of oculus) started to evolve and their traceries began to be used for designs ; the designs would get increasingly complex and began to take the shape of a rose, hence the term ‘rose window’, which didn’t take its name until the 17th century.

The windows absorbed cultural styles of the region they were built in. Great examples are the Troia Cathedral in Italy and the San Lorenzo church in Spain, which bear clear islamic influence, due to the Moor occupation of the 8th century. This is also the time that oculi began to evolve, which could indicate the possible origin of designs inside the oculus altogether.

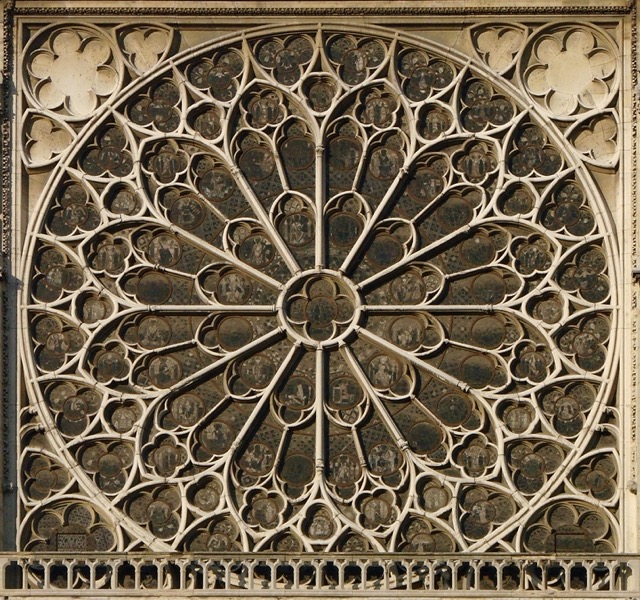

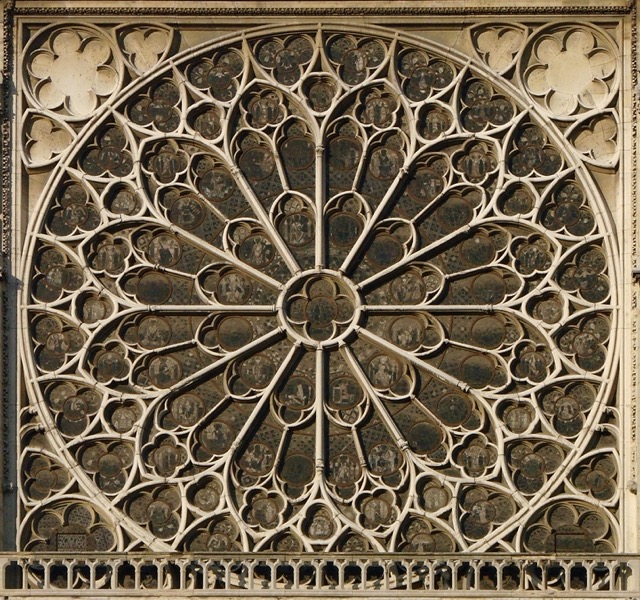

By the 12th century, the archetypal rose widow, whose style is known as “Rayonnant”, was born in France. The most famous is the Notre Dame rose window in Paris. From this “Rayonnant” style are born many more, such as the Curvilinear and the Flamboyant.

From here on, rose windows would continue to spread to the rest of the world. They underwent periods of destruction, renaissance and modernization. They got restored over and over again and still live on today as a religious relic.

So what is it about rose windows that have fascinated the medieval world, which many of us haven’t a clue of?

For its creators, the classic rose window represented a range of fundamental concepts. They are:

- Light

- Circle

- Cycle

- Order

- Geometry

These concepts are expressed through the rose window’s shape, material, stained glass images and colour, and exterior tracery design.

The 5 Fundamental Concepts of the Rose Window

Light

The rose window displays light, both physically and symbolically. First, there’s the outside light that seeps into the cathedral through the rose window. As it does, the stained glass turns it into colourful lights. This gives the allure that ‘through light, comes the universe”.

This idea is fundamental to the medieval Christians, because light is one of the first thing that the biblical god created. Virtually all religions and myths contain a Creation narrative. In them, light isn’t necessarily the first thing created, however, it is often associated with high ranking creator deities, such as Zeus, Ahura Mazda, Ra and Brahma.

The ancients’ association of light with ‘creation’ is likely due to the importance of the sun’s life-giving energy to the planet.

They aren’t far off from modern science’s view on the creation of the universe. According to today’s leading theory, the universe began with a big bang of energy. From that initial burst, eventually came the many galaxies of stars and planets. This idea of “one form of energy producing a myriad of things” is reflected in the ancient Taoist saying “The ten thousand things”. Which draws our attention back to the rose window; from the white light comes the many colours that exist.

Medieval rose window creators have also shown the importance of light through symbolism, using Christ. Christ represents light. Christ or god would be put at the centre, because according to Christians, it is through them that everything exists. In other words, through light, everything exists creating a universe. Note that there are many non-creator deities who also represent light in world myths, such as Sol and Apollo, both of which have been associated with Jesus.

Circle

To the medieval thinker, the universe, or god, is a circular shape. This is illustrated with the image of “god” drawing a circle with a compass.

A popular saying among theologians at the time was that “God is an infinite sphere whose circumference is nowhere and whose centre is everywhere”. This expression is found in the Liber XXIV Philosophorum, a latin booklet consisting of definitions of what God is.

Today, the shape of the universe is a topic of great debate. There are 3 leading theories. 1) The universe has a positive curvature (spherical) 2) The universe has a negative curvature (saddle-shape) 3) The universe is completely flat. The jury is still out.

Regardless, the circle has been a sacred shape for many ancient religions. It is often referred to as a wheel (another name for the rose window: wheel window). There is for example, the norse Sun Wheel, the buddhist Dharma wheel and the native American Medicine Wheel, which are all associated with light and sun.

The shape of the sun as well as the cycles associated with it, could have largely contributed to the medieval idea of the universe and god as a circle.

Cycle

The circular shape of the rose also conveys cycles, and that all things are subject to the eternal cycle of the universe – planets, time, seasons, even personal life events. A well-known medieval allegory seen on rose windows is that of Fortuna and her wheel. Fortuna is the goddess of ‘fate’ and she controls the wheel of fate.

There are smaller figures around the wheel. They are actually one figure whose stature changes depending on where the wheel guides it. At the top, the person reigns, then, he dips into misfortune, and makes his way back up again. The allegory wishes to express the inescapable cycle of fortune and misfortune, good and bad, victory and losses for all humans with no exception.

There are rose windows that show the embodiment of vices and virtues along with the zodiac signs. Some believe that it illustrates the ongoing struggle of the soul throughout daily life – known as “psychomachia”.

Others think that it’s a reflection of the medieval belief in astrology; where the positions of stars and planets at the time of a person’s birth influences their personality which includes vices and virtues.

But I’d like to think that it represents the inevitable cycles of vices and virtues societies as a whole go through.

Cycles are found everywhere which leads us to the next point.

Macrocosm-Microcosm relationship

The late middle ages were very keen on the subject of macrocosm-microcosm relationships, famously expressed as “As above so below”. In essence, the human body and the affairs of humans were like the universe, on a smaller scale. This relationship is frequently found on rose windows as the 12 constellations in the sky vs. the 12 labours of the year.

Constellations are a group of stars that have been named based on the patterns they form. There are 88 recognized constellations.

The 12 constellations that form the zodiac, are those that the sun appears to pass through in a circular path from the perspective of the earth, which orbits the sun once a year.

Constellations of the sky are parallel to the labours of the year; the time it takes the earth to go through those 12 constellations is a year, which is also divided into 12 months, each represented by the labour that is associated with that month.

Order

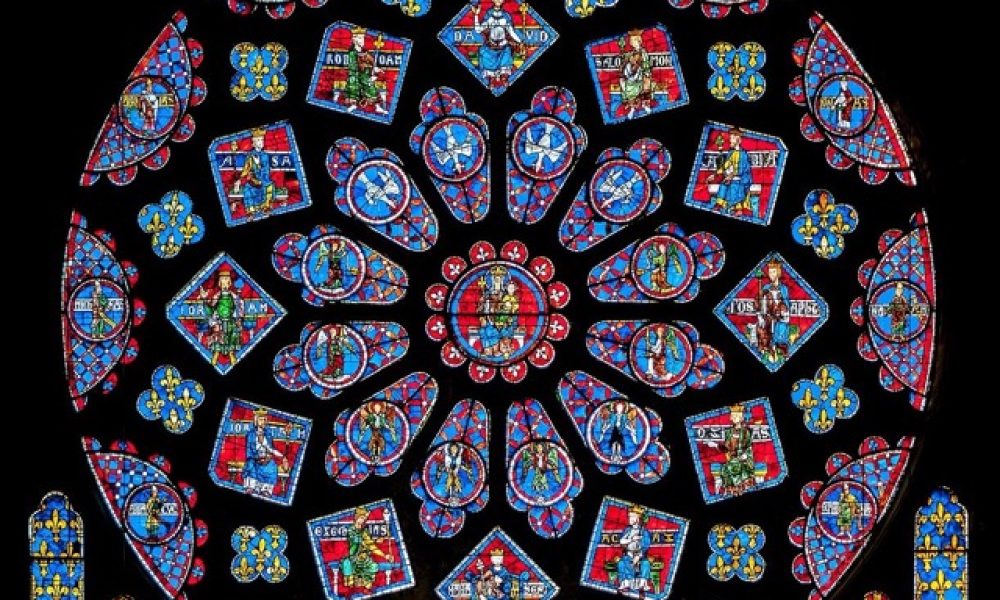

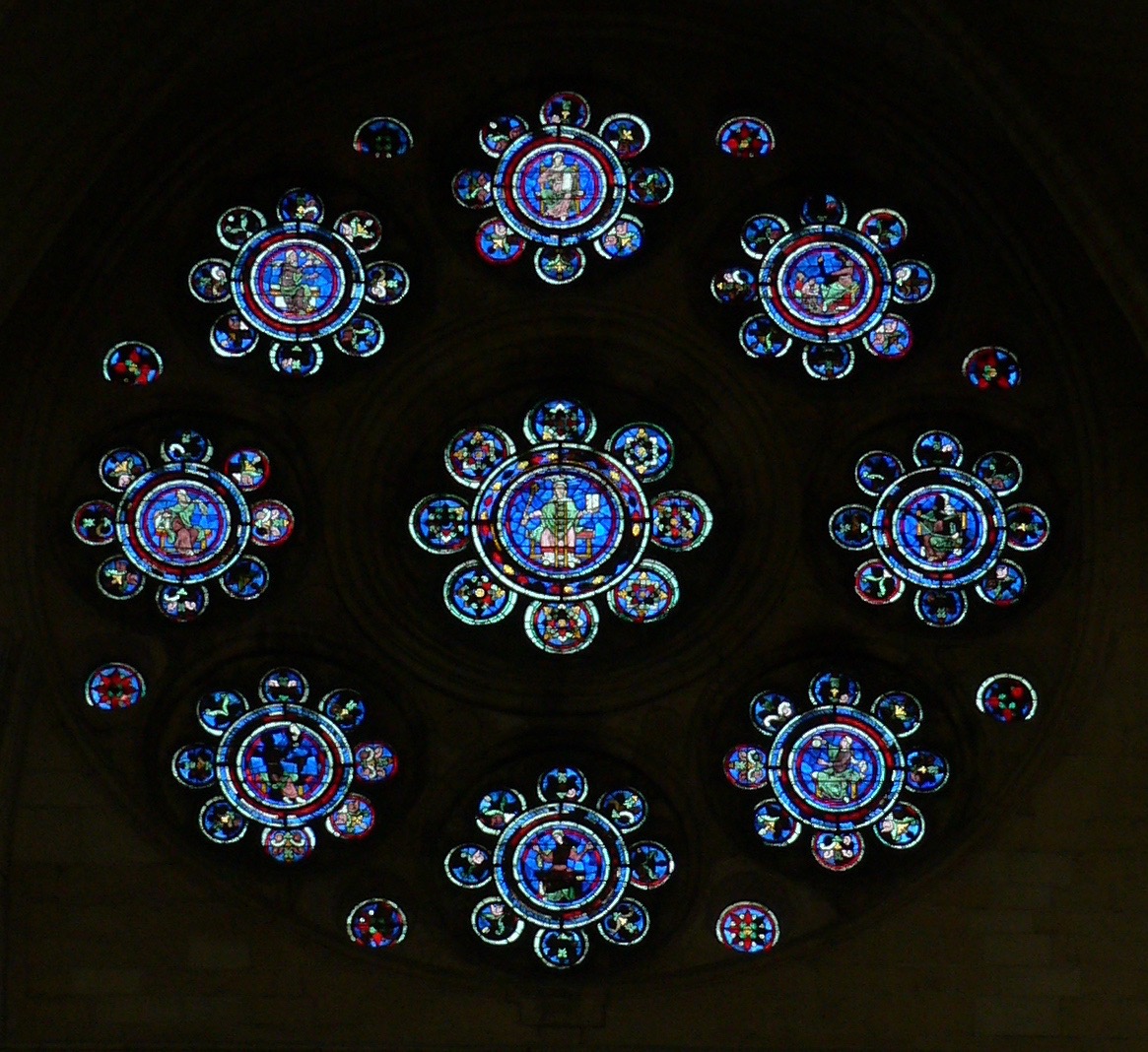

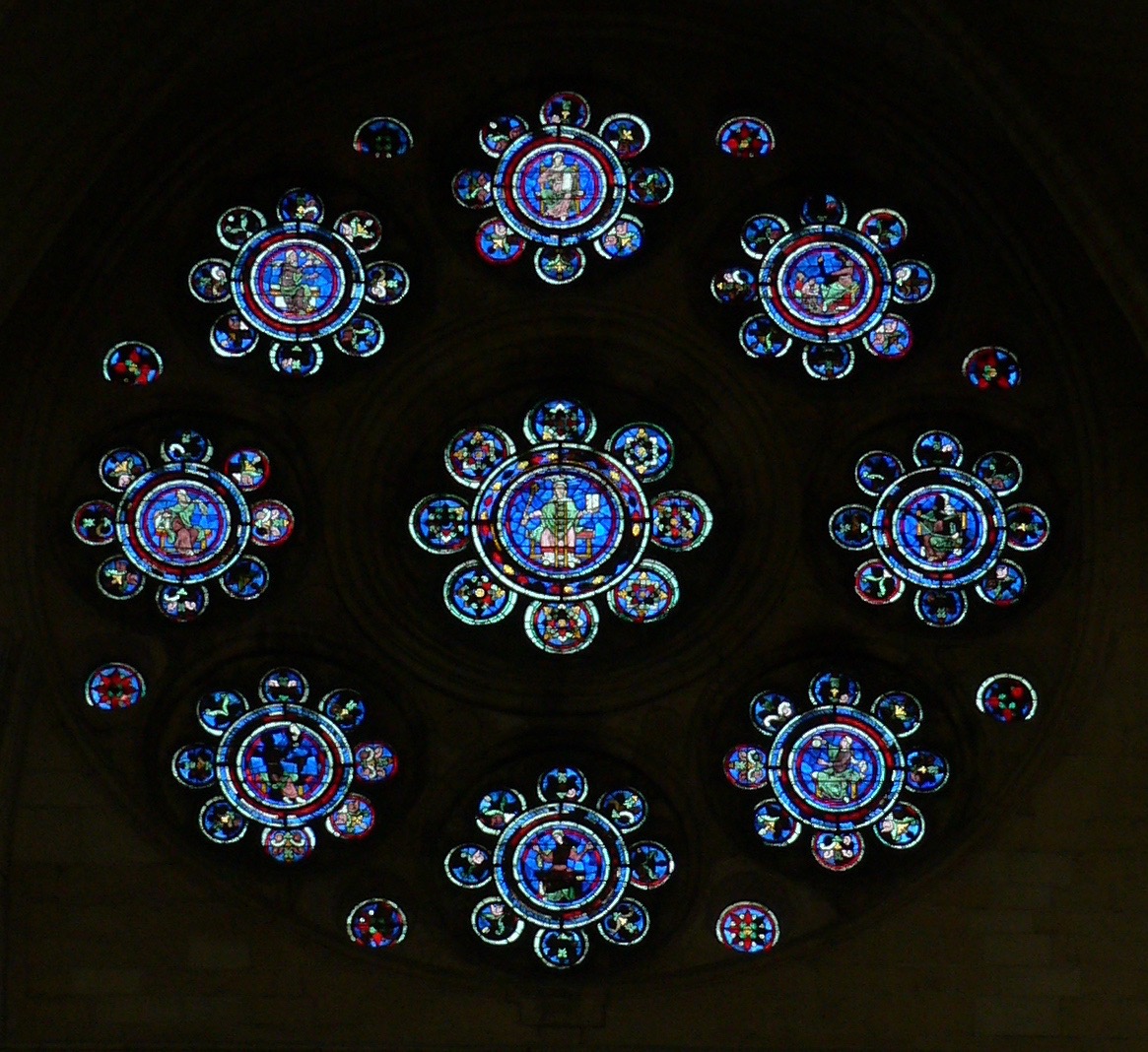

Order and hierarchy are popular themes in rose windows, especially with Christian narratives. Christ would be at the center, and from him emanate the Christian themes. Often, it’s the Virgin Mary at the center; from her emanates the life of Jesus. The shape of the circle helps give the appearance of a sequence. .

In some windows, like that of the Chartre Cathedral, non-Christian elements are combined to add meaning. Zodiac signs – expressing time, the heavens and human affairs – are seen surrounding Christ, indicating that his divinity rules the entire cosmos.

Sometimes, rose windows only display pagan iconographies or representations of elements.

Philosophy is a popular figure in rose windows. This Greek derived word literally means “love of wisdom”. In the Laon cathedral rose window, Philosophy placed at the center is an attempt to show that the mind is at the center of all.

Education was crucial. The medieval erudites believe that in order to elevate the mind, a society or the ‘man’ must be proficient in the 7 liberal arts. This is expressed by Philosophy , at the center, being surrounded by the personification of each liberal art; grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, music , arithmetic, geometry and astronomy. The cathedral of Laon adds medicine to make it more complete.

Geometry

Lastly, we have “geometry”, the expression of mathematical and cyclic patterns that occurs in the heavens as it occurs below it. The rose window, full of geometrical pattern, was ultimately the expression of the universe.

In fact, all the themes we’ve spoken of – light, cycle, microcosm/macrocosm, order and geometry – have to do with the universe. The cosmos. Some patrons of rose windows have even wanted to encapsulate all that makes up the cosmos into a single rose window, such as the Lausanne window, which meshes in an orderly fashion, the year, seasons, months, winds, heavens.

The need to explain the universe is one of humanity’s strong impulses. All cultures, at one point or another, are driven to pack their cosmological and philosophical views into a geometrical symbol. The Chinese do so with their Yin yang symbol. Muslims with their geometrical art on their mosques. In medieval Europe, this was done through the Rose Window.