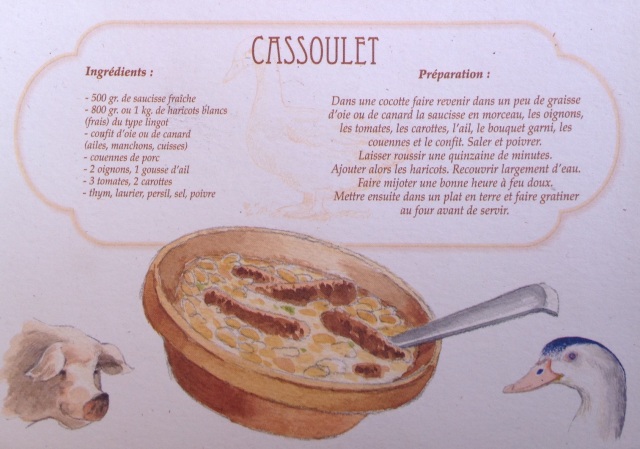

The definition of a cassoulet, according to Wikipedia, is ‘a rich, slow-cooked casserole originating in the south of France that contains a combination of meats – typically pork sausages, goose or duck confit, (sometimes mutton), pork skin (couennes) and white haricot beans’. Research to date indicates that a really good cassoulet is dependent on a several things. First and foremost for this totally biased writer is the dish in which it is cooked, second (and ultimately the most important) are the ingredients and finally – time. This is not a dish to be prepared in a hurry.

Research to date indicates that a really good cassoulet is dependent on a several things. First and foremost for this totally biased writer is the dish in which it is cooked, second (and ultimately the most important) are the ingredients and finally – time. This is not a dish to be prepared in a hurry. Which is how Brunyfire came to find herself wedged between sister Stef and brother-in-law George in their little blue water tank on wheels, barreling up the A64 motorway towards Toulouse from the village of Lherm. Bypassing Toulouse city, we head south towards Castelnaudry and Carcassone towards the little town of Labastide-d’Anjou, in the Languedoc-Roussillon region, France.

Which is how Brunyfire came to find herself wedged between sister Stef and brother-in-law George in their little blue water tank on wheels, barreling up the A64 motorway towards Toulouse from the village of Lherm. Bypassing Toulouse city, we head south towards Castelnaudry and Carcassone towards the little town of Labastide-d’Anjou, in the Languedoc-Roussillon region, France.

It’s August 2015 – it’s hot and glorious and France is looking lovely. The search is on for the dish (as in the cuisine and the pot in which it is cooked) that symbolizes the region — the Cassoulet. The cassoulet gets its name from the cassole or casserole that’s used to cook this classic dish – a deep, round, earthenware vessel with a narrow base and slanting sides that flare out to a wide top that maximises exposure to the oven’s heat, thus helping to form the cassoulet’s signature crust. Cassoles from this region are made from a mixture of clays that come from the Lauragais region around Castelnaudry and are known for their heat resistant qualities.

Cassoles from this region are made from a mixture of clays that come from the Lauragais region around Castelnaudry and are known for their heat resistant qualities. The cassoles, and other kitchen vessels have been made locally in this area since the 14th century, and one of the oldest artisan manufacturers still in existence is the NOT family pottery studio – Poterie Not – located just beyond Labastide d’Anjou on the banks of the Canal du Midi near the village of Mas Sainte Puelle.

The cassoles, and other kitchen vessels have been made locally in this area since the 14th century, and one of the oldest artisan manufacturers still in existence is the NOT family pottery studio – Poterie Not – located just beyond Labastide d’Anjou on the banks of the Canal du Midi near the village of Mas Sainte Puelle.

A pottery has been on this site since the 1830s, and has had various owners up until 1947 when it was taken over by Emile Not, the grandfather of the brothers Aimé and Robert Not who continued to run the pottery together until Aimé’s death in 2008. It is now the oldest pottery in the South of France and is the only place in the country where the cassole is still made by hand. Currently it is being worked by Robert Not, Aimé’s son Jean-Pierre and Robert’s son, Philippe.

A pottery has been on this site since the 1830s, and has had various owners up until 1947 when it was taken over by Emile Not, the grandfather of the brothers Aimé and Robert Not who continued to run the pottery together until Aimé’s death in 2008. It is now the oldest pottery in the South of France and is the only place in the country where the cassole is still made by hand. Currently it is being worked by Robert Not, Aimé’s son Jean-Pierre and Robert’s son, Philippe.

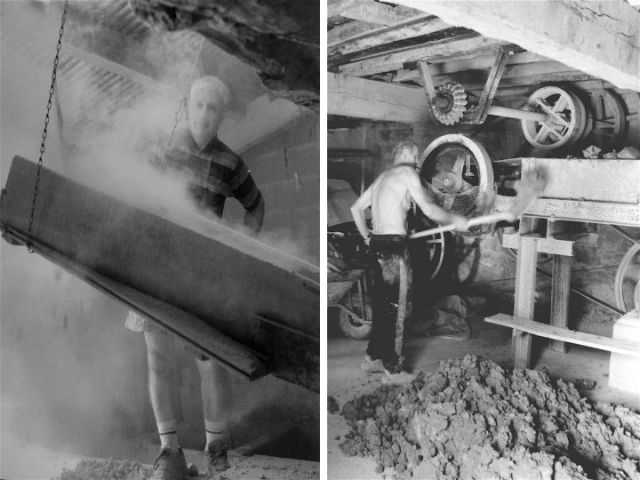

During the time of our visit, the Not family were taking a lunch break and Jean-Pierre invited us to look around until such time as they were back on their wheels. Their clay comes from a seam on the property and is combined with a red clay from nearby Issels. This is dumped on the concrete at the back of the workshop and allowed to dry, before being crushed by steel rollers, sieved, then mixed with water (and grog if required) and allowed to slake in the outdoor settling tanks. Once plastic, the clay is shovelled manually into the mouth of the mixer, an ancient piece of machinery dating from the 1940s containing viscous rotating blades.

Once plastic, the clay is shovelled manually into the mouth of the mixer, an ancient piece of machinery dating from the 1940s containing viscous rotating blades.  From the mixer, it progresses through the pug mill where 20 kg blocks are extruded at a time, and these are wheeled off to the throwers next door.

From the mixer, it progresses through the pug mill where 20 kg blocks are extruded at a time, and these are wheeled off to the throwers next door.

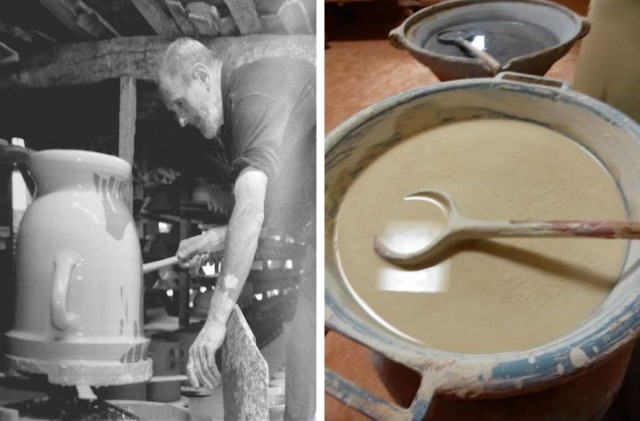

Sitting ‘side saddle’ rather than astride his wheel, Jean-Pierre proceeds to throw with an easy grace and speed that has several medium sized Cassoles lined up on the ware board beside him in the time it takes Brunyfire to get her camera sorted out. Grabbing a lump of clay from the extruded block, knowing this will be enough to provide the size cassole required, is an instinctive act – the clay is patted firmly a couple of times as the wheel rotates, and it’s centered! Jean-Pierre’s slip encrusted apron crackles with every movement as he maintains the momentum of a continuous flow of work whilst bantering with Stef. But then, they’re used to this, and work can’t stop, even when engaging with the many visitors the pottery receives.

Sitting ‘side saddle’ rather than astride his wheel, Jean-Pierre proceeds to throw with an easy grace and speed that has several medium sized Cassoles lined up on the ware board beside him in the time it takes Brunyfire to get her camera sorted out. Grabbing a lump of clay from the extruded block, knowing this will be enough to provide the size cassole required, is an instinctive act – the clay is patted firmly a couple of times as the wheel rotates, and it’s centered! Jean-Pierre’s slip encrusted apron crackles with every movement as he maintains the momentum of a continuous flow of work whilst bantering with Stef. But then, they’re used to this, and work can’t stop, even when engaging with the many visitors the pottery receives.

Once the ware is dry enough to handle, the pieces are then ‘slipped’……..

…….ie, coated in an engobe (a white or colored clay and water solution, or slip coating that is applied to a ceramic body to give it decorative color or improved texture), then glazed.

…….ie, coated in an engobe (a white or colored clay and water solution, or slip coating that is applied to a ceramic body to give it decorative color or improved texture), then glazed.

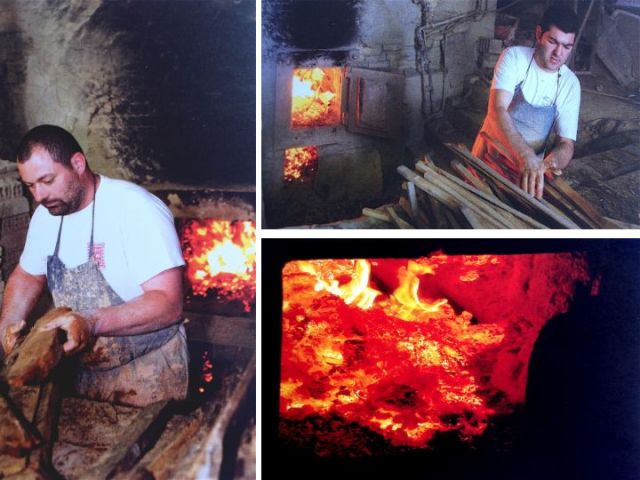

The functional ware produced at Poterie Not are all fired every day in the two gas fired kilns, whilst the bigger stuff, all the flowers pots, are wood fired once a month. Pots are stacked in the wood kiln without shelves….. …….and once full, the door of the kiln is bricked up and sealed with slurry. The firing usually takes around 36 hours and is fired to 1000 degrees c, after which it is allowed to cool for three weeks before being opened and unpacked.

…….and once full, the door of the kiln is bricked up and sealed with slurry. The firing usually takes around 36 hours and is fired to 1000 degrees c, after which it is allowed to cool for three weeks before being opened and unpacked.

The Not workshop is a complex maze of narrow corridors and low ceilinged rooms – the dust motes of years of working with clay float up from our feet as we explore, glittering with beautiful menace in those shafts of sunlight that manage to find their way into the depths of this Aladdin’s cave. Everywhere there are pots in various stages of production – from drying upstairs in the loft above in the lingering warmth of the last wood firing to the stacks of orders glistening in the sun on the floor of the stock room.

The Not workshop is a complex maze of narrow corridors and low ceilinged rooms – the dust motes of years of working with clay float up from our feet as we explore, glittering with beautiful menace in those shafts of sunlight that manage to find their way into the depths of this Aladdin’s cave. Everywhere there are pots in various stages of production – from drying upstairs in the loft above in the lingering warmth of the last wood firing to the stacks of orders glistening in the sun on the floor of the stock room. Jean-Pierre obligingly hauls himself of his wheel to attend to our sales – no credit cards here – only cash which he places in a battered tin box that emerges from somewhere amongst the pile of paperwork teetering on his desk in the office.

Jean-Pierre obligingly hauls himself of his wheel to attend to our sales – no credit cards here – only cash which he places in a battered tin box that emerges from somewhere amongst the pile of paperwork teetering on his desk in the office.

The work of Poterie Not is honest – the marks of the potters hand in throwing and glazing are clearly evident and not disguised. The ware is rugged, rustic and is intended for use. The cassoles we purchase are just itching to be put into service………..