Quick! Name three things about rattlesnakes!

If, like me, your knowledge comes from westerns and the bad guy from Rango, it was “deadly”, “rattling” and “desert”, wasn’t it?

The Sinaloan long-tail probably isn’t the first one, and definitely isn’t the second or third one. So forget everything you think you know about rattlesnakes.

At a fairly dinky 79cm (31 inches), the Sinaloan long-tail isn’t exactly imposing. But with its orange-brown dorsal patterns that veer between “two kissing diamonds” and “mini Bat-Signal”, it’s pretty striking.

Photo by Dr. Albert M. Van der Heiden.

And it’s only “striking” in a visual sense. It’s not aggressive, and had no qualms being picked up and plopped in a plastic jar by Van der Heiden and Flores-Villela. But that’s not to say you should go and poke it if you’re lucky enough to see one.

For a start, Meik et al. claim it has “exceptionally long fangs” for a rattler, and since it’s a pretty elusive slitherer, we don’t have enough records to know how dangerous its venom is. Odds are its bite would be pretty painful, and maybe involve some kind of paralysis, so hassling it would make you an idiot as well as rude.

Speaking of idiots, rattlesnakes are what’s known as pit vipers after the heat-sensor “pits” next to their eyes, not some snake-filled death-hole a crazy villain would throw you into. Which is what I thought it was.

If this doesn’t sound very impressive, fear not. Because this is a snake that goes where many humans fear to tread, and was forged in fire and brimstone. Sort of.

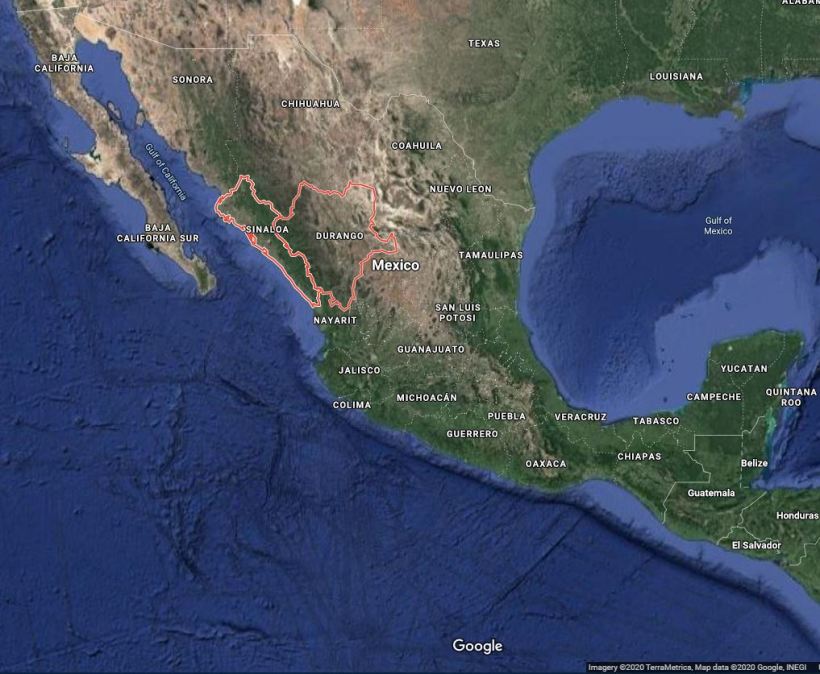

Found in western Mexico along the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains, western Durango and (wouldn’t you know it) southeastern Sinaloa, this little rattler might have a wider range than we think.

But we don’t know for sure, because we’d need to brave roads that are pretty much inaccessible in the rainy season, and the other type of no-go areas – the ones rife with drug crime!

The Sinaloan long-tailed rattlesnake isn’t a stranger to barriers, though. Reyes-Velasco et al. think it first split off from Mexico’s other long-tailed rattlers, Crotalus lannomi and the Guerreran (Crotalus ericsmithi), about 3.9 million years ago in the Pliocene, back when we were lumbering about being Australopithecus.

The nearby volcanoes were already a million years into blowing their tops along the Jalisco-Nayarit state boundary, and adapting to the change in habitat and journey north may have made the Sinaloan long-tail what it is today.

And as far as the locals are concerned, that’s the víbora sorda, or “muffled viper”.

You can’t really blame it when its rattle is only 12mm (0.47 inches) long and 4mm (0.15 inches) wide.

See where the grey-blue tail changes colour above her left eye? That’s it. It’s so teeny! Photo by Dr. Albert M. Van der Heiden.

According to Van der Heiden and Flores-Villela, it made a soft buzzing noise, like a cicada, that could be heard up to 60cm (23 inches) away. So if it’s meant to be a warning, as we suspect the rattling might be, perhaps it relies on offensiveness rather than volume.

As in other rattlers, the rattle itself starts out as a deceptively cute-sounding “button” at the end of the newborn’s tail, and then with each moult, which can be multiple times a year, an extra hollow layer is added on. Once it has three of them, it can start making some noise, even if it’s just a small buzz.

It’s impressed snake experts in other ways, though. Fnar fnar.

I tore myself away from talking about snake genitals last time, but according to Klauber, the Sinaloan long-tail’s are worthy of note. At least when it comes to the chaps.

Before the larger lady snakes can pop out young, they need some attention from the males’ hemipenes – basically two penises that form a V-shaped, retractable appendage on their underside. Klauber thought that those of the Sinaloan long-tail were “the most distinctive of all rattlesnakes”.

As you can imagine, I spent countless hours finding out exactly why, but the most I came away with was that for some reason, certain parts of the lobes, which make up each hemipenis, were more compressed than in other species. So let’s leave it at that.

If you’re wondering how the ladies fare in all this, our info is rather limited. Rattlesnakes can do the coiled conga for hours, and Van der Heiden, the first to breed the Sinaloan long-tail in captivity, found the pair didn’t take the plunge until they’d hit at least 4 years of age, and that it took a good 10 months for the female to brew up some babies.

Chap on the left, lady on the right. You can see the difference in body shape and head patterns. Photo by Dr. Albert M. Van der Heiden.

To avoid any mess, they hatched inside her body before being born live, and despite the delicious size of the newborns, neither Mum nor Dad were partial to a snack. Although they parted ways as soon as they were released to the wild, the family seemed incredibly chilled in each other’s company. So the Sinaloan long-tail may be cold-blooded, but not as a parent.

Another way it stands out from the crowd, or at least its snaky stereotype, is its choice of digs.

Slithering about between 400 and 1,200 metres (1,312 and 3,937 ft) elevation, the Sinaloan long-tailed rattlesnake prefers tropical deciduous, pine and oak forests, and may or may not be fond of water.

The specimens Van der Heiden and Flores-Villela looked at were almost always hanging around after fog, heavy rain or thunderstorms, and in the dry season, near a man-made reservoir. So it either enjoys a splash, or is frequently annoyed at being flooded out of house and home.

If the latter, it must be extra angry about all the deforestation. It’s not quite as far down the endangered road as Bambour’s montane pit viper – the snaky pal it was first discovered with – but it probably isn’t far off. What’s more, the Sinaloan long-tail is only found in primary forest and not at all in any Federal Natural Protected Areas.

But there is hope. There are plans to expand the Monte Mojino conservation reserve to cover La Guásima and El Habal de Copala, where at least one of the jarred rattlers came from. And if a quietly rebellious snake honed by flames and impressive genitals isn’t worth saving, then, quite frankly, nothing is.

TLDR

The Sinaloan long-tailed rattlesnake is a rare little Mexican snake that prefers forests to deserts, has a teeny rattle, and as far as rattlesnakes go, distinctive male bits!

Latin: Crotalus stejnegeri

Latin: Crotalus stejnegeri

Crotalus is from the Greek for rattler, “Crotalum”, and stejnegeri is for Norwegian herpetologist and later Smithsonian Institute curator Leonhard Hess Stejneger. The snake’s discoverer, E.R. Dunn, named it in his honour for “all the encouragement” he had shown him. Aww.

Where? Western Mexico, in tropical deciduous, pine and oak forests.

How big? Females up to 79cm/31 inches long, males about 72cm/28 inches.

Endangered? Considered Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, mainly due to habitat loss from logging and farmland. People’s attitude to rattlesnakes probably complicates things too.

It sounds cool! Does it need my help at all?

Yes, the aforementioned deforestation is carving up its territory, and local attitudes towards snakes aren’t exactly stellar. Save the Snakes has various local and international campaigns to help our slitherers, and Conselva, along with CIAD A.C. (Research Centre for Food and Development) are pushing for Monte Mojino to become a Natural Protected Area.

I’d like to say a huge thank you to Dr. Albert M. Van der Heiden, who was kind enough to send me multiple photos of this awesome little snake, as well as some extra info I’d never have found!

Just to prove I’m not fibbing:

Canseco-Márquez, L., Campbell, J.A., Ponce-Campos, P., Muñoz-Alonso, A. & García Aguayo, A. 2007. “Mixcoatlus barbouri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species” 2007: e.T64305A12761692.

Collins, Joseph T. 1982. “Crotalus stejnegeri, longtail rattlesnake“. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles.

“Crotalus horridus Linnaeus, 1758 — Timber Rattlesnake“. No date. Illinois Natural History Survey. Prairie Research Institute.

“Crotalus stejnegeri“. No date. Clinical Toxinology Resources. University of Adelaide.

“Crotalus stejnegeri DUNN, 1919“. No date. Reptile Database.

Dunn, E.R. 1919. “Two new crotaline snakes from western Mexico“. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 32:213-216.

Funk, Richard S. 2006. “Snakes:Reproductive and Urinary Systems“. Reptile Medicine and Surgery.

Jadin, Robert & Reyes Velasco, Jacobo & Smith, Eric. 2010. “Hemipenes of the long-tailed rattlesnakes (Serpentes: Viperidae) from Mexico“. Phyllomedusa : Journal of Herpetology. 9(1): 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v9i1p69-73.

Meik, Jesse M., Sester, Kirk, Mociño-Deloya, Estrella, Lawing, Michelle A. 2012. “Sexual differences in head form and diet in a population of Mexican lance-headed rattlesnakes, Crotalus polystictus”. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 106(3):633-640.

Mendoza-Quijano, F. 2007. “Crotalus stejnegeri. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species” 2007: e.T64333A12771355.

Reyes-Velasco, Jacobo, Meik, Jesse M., Smith, Eric N., and Castoe, Todd A. 2013. “Phylogenetic relationships of the enigmatic longtailed rattlesnakes

(Crotalus ericsmithi, C. lannomi, and C. stejnegeri)”. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 69:524-534.

Van der Heiden, Albert M. 2019. “Crotalus stejnegeri (Sinaloan Long-tailed Rattlesnake). Reproduction in captivity.” Herpetological Review 50(4):742-743.

Van der Heiden, Albert M., and Flores-Villela, Oscar. 2013. “New records of the rare Sinaloan Long-tailed Rattlesnake, Crotalus stejnegeri, from southern Sinaloa, Mexico“. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 84(4):1343-1348.

Wallach, Van. No date. “Rattlesnake“. Britannica.com.

Wong, Kate. 2019. “The face of the earliest human ancestor, revealed“. Scientific American.

Featured image credit: Dr. Albert M. Van der Heiden.

Actually my three words were “pattern”, “rattle” and “fast”. Snake patterns can be such intricate, beautiful designs.

LikeLiked by 1 person