Even if I tell you that the pygmy sperm whale squirts ink, sinks like a submarine and uses a secret code, your first question will still probably be: “why is it called a sperm whale?”

Just to get this out of the way: because it was indeed named after sperm. Or rather, the white gunk whalers found cutting into regular sperm whale’s head (Physeter macrocephalus).

And even if it didn’t have the same head gunk, the pygmy would still have inherited the name, because it’s one of regular sperm whale’s two closest relatives.

It keeps its secrets in the family, because we’re not 100% sure what this “spermaceti” stuff is. (Well, except that it’s not sperm.)

Since it hardens like wax at certain temperatures, one theory is that it helps this little deep-diver control its buoyancy. Said deep dives are partly why, yet again, we know so little about an animal with such a notorious name.

Its various disguises can also keep us in the dark.

It’s a squid!

If you dive up to 3,500 metres (11,482 ft) into the bathypelagic or “midnight zone” of the ocean, where some horrific bitey things live, you learn a few tricks. Sometimes from the very things you yourself prey upon.

When startled, the pygmy sperm whale can blast 11 litres (3 gallons) of dark red liquid into an enemy’s face. In polite company you’d say it’s ink, but it really comes from a sac in its lower intestine, so let’s leave it at that.

I’d say it’s the natural response to a great white shark going for you, and since orcas have been spotted attacking its smaller relative, the dwarf sperm whale (Kogia sima), it’s a safe bet it has a spot on their menu too.

Fortunately, it’s good at keeping a low profile, even on the surface.

It’s a submarine!

Veteran whale-watchers will know to look out for the “blow” of air and water, or a rising and falling tail-fluke after a whale takes its breath.

Although the pygmy sperm whale very clearly breathes, it neither blasts a shaft of air and water nor pokes its tail up.

Instead it “logs”, by hanging still or swimming slowly just under the surface, and then sinks like a little submarine. It’s small and darkly coloured to boot, so you’d be right in thinking it’s hard to spot – “65% chance of failure” hard, going by Barlow or Hodge et al.’s visual surveys. And if that doesn’t make it stealthy, how about this: it may have its own communication channel.

Even though it’s a deep diver, the pygmy sperm whale has been recorded making narrowband, high frequency clicks around and above 100kHz. These are usually reserved for short-range echolocation in shallow water, mostly by porpoises or the four small dolphins of the Cephalorhynchus crowd. (Hector’s dolphin says “Hi!”)

Madsen et al. think this is because at these frequencies there’s less ambient racket going on, and more importantly, the local orcas start needing an ear trumpet. Before you scoff, I remind you that human hearing tops out at a piffling 20kHz.

While it seems adept at avoiding its enemies, the pygmy sperm whale puts far less effort into catching its own food.

It’s a hoover!

It’s harder to chomp bony fish when you don’t have any top teeth, so the pygmy sperm whale usually snacks on soft cephalopods (squid and octopus) and crustaceans. Sometimes it will swim into a swarm of prey and basically suck in the foody goodness.

Unfortunately this isn’t the best tactic, because plastic rubbish can also look like an enticing snack, and some stranded pygmy sperm whales have been found with their guts full of literal junk food.

At least we don’t see the pygmy sperm whale as junk food. On a (slightly) brighter note, it doesn’t seem to be yanked up as by-catch all too often, which is both good and bizarre considering its appearance.

It’s a fish!

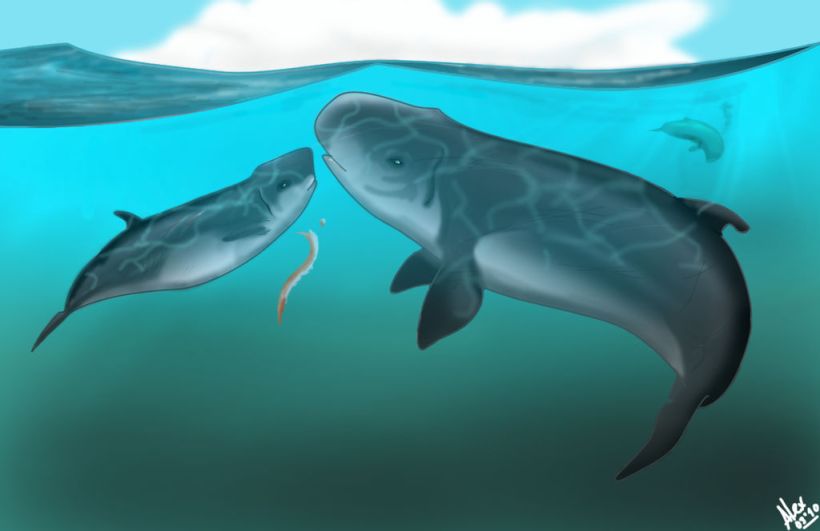

Futurama‘s Mushu, the pygmy sperm whale, looks just like a miniature sperm whale. While technically correct (as in “a small version of a sperm whale”), the true pygmy’s head is shorter and rounder and more shark-like. It also has a curious c-shaped mark or “false gill” behind its eye.

Even though it looks like a fish, it spent a good few years being mistaken for something else.

It’s another type of sperm whale!

We first thought it was a pocket version of the sperm whale, and although they’re related, the pygmy belongs to a different genus (Kogia). So no underwater shenanigans if they ever want grandchildren.

It also shares this genus with the aforementioned dwarf sperm whale, and wouldn’t you know it, we thought they were the same species until 1966.

We’re not going to find out much more without some SCUBA gear, because as well as being secretive, the pygmy sperm whale doesn’t do well in captivity. I’ll spare you all the depressing stats, but according to Bloodworth and Odell in 2008, the longest stint survived was 21 months. (By the whale, not its keepers.)

Fortunately, the wild pygmy sperm whale seems pretty widespread, so no news is good news on this one.

Keep up the good work, little sea spy!

Pygmy Sperm Whale Fact File

Latin: Kogia breviceps

Ranneft et al. think “Kogia” might be in honour of Turkish naturalist Cogia Effendi, while breviceps means “short head”.

What? A dinkier relative of the massive sperm whale.

Where? Deep waters pretty much worldwide. It dives at least as deep as 2,000m /6,561 feet, and possibly as much as 3,500m/11,482 feet (both in the bathypelagic, or “midnight zone” of the ocean).

First recorded? Somewhat gruesomely, from a head. de Blainville documented it as Physeter breviceps – “whale/blow pipe with a short head” – in 1838 after the regular “whale/blow pipe with a large head” sperm whale, Physeter macrocephalus. Gray then changed this to Kogia breviceps in 1849.

How big? Up to 4.25 metres / 13.9 feet long.

Diet? Mostly cephalopods i.e. squid and octopus, but also crabs and small fish.

Behaviour? It’s usually seen on its lonesome or in groups of up to seven, but this could be of any age or gender, so we have no clue what its social links might be. Cows will pop out one calf after 9-11 months, and in the Northern Hemisphere there’s a baby boom between March and August.

Endangered? Hopefully not, as we’re aware of several populations, but it’s so seldom seen it’s hard to be sure. It’s considered “Least Concern” for now.

Featured image credit: “Kogia sima – Kogia breviceps” by AngelMC18.

Just to prove I’m not fibbing:

Bloodworth, Brian E., and Odell, Daniel K. 2008. “Kogia Breviceps (Cetacea: Kogiidae)“, Mammalian Species 819:1–12.

de Blainville, M.H. 1838. “Sur les cachalots“, Annales françaises et étrangères d’anatomie et de physiologie, 335-337.

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. No date. “Spermaceti“. Britannica.com.

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. No date. “Sperm whale“. Britannica.com.

Kiszka, J. & Braulik, G. 2020. “Kogia breviceps“. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T11047A50358334.

Lundrigan, Barbara, and Myers, Allison. No date. “Kogia breviceps“. Animal Diversity Web.

Madsen, P.T. et al. 2005. “Porpoise clicks from a sperm whale nose—convergent evolution of 130kHz pulses in toothed whale sonars?“, Bioacoustics 15(2):195-206.

“Physeter“. No date. Merriam-Webster.

Price, M. C. et al. 1984. “Treatment of a strandling whale (Kogia breviceps)“, New Zealand Veterinary Journal, 32(3):31-33.

“Pygmy sperm whale“. No date. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Ranneft, D.M. et al. 2001. “A guide to the pronunciation and meaning of cetacean names“, Aquatic Mammals 27(2):183-195.

“Sperm whale“. No date. National Geographic.

Whitehead, Hal. 2008. Encyclopaedia of marine mammals (third edition). Science Direct.