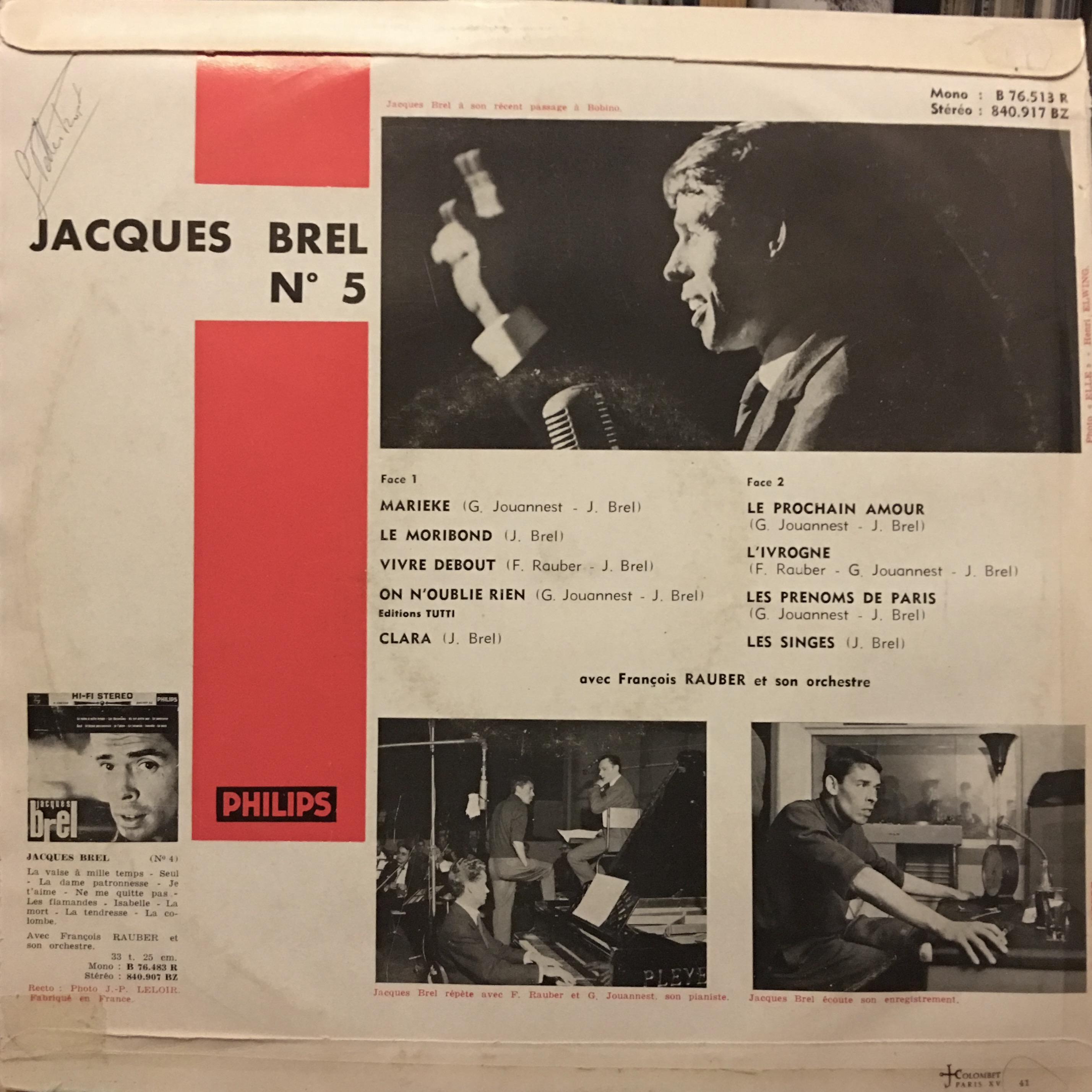

Two years after Brel’s fourth album, which was a striking collection of juxtaposed pieces including the hits ‘Ne Me Quitte Pas’ and ‘La Valse A Mille Temps’, Brel released No. 5.

Released in April 1961, the album followed Brel’s breakthrough success in North America, the Middle East, and the Soviet Union. On this album, we see Brel experiment with Latin American rhythms on tracks like ‘Clara’, ‘Les Singes’ (‘The Apes’), and ‘Vivre Debout’ (‘Living Standing Up’), explore the language divide between Flemish and French speaking Belgians on the multi-lingual ‘Marieke’, and paint a humorous yet touching depiction of death in ‘Le Moribond’ (‘The Dying Man’).

The album is relatively introspective compared to the previous releases we have seen from Brel – here we see him expose vulnerability, explore the language divide between French-speaking and Flemish Belgians, and attack the concept of civility.

‘Marieke’ opens the album, and is one of Brel’s most interesting pieces from a conceptual perspective. Here, Brel’s thoughts on the cultural and linguistically divide between the Flemish and French Belgians are expressed in a Romeo and Juliet style love song, which sees a French-language narrator express his love for the Flemish Marieke – whom no longer loves him.

This is followed by ‘Le Moribond’ (‘The Dying Man’) – which became an international hit when translated as ‘Seasons In The Sun’ by Rod McKeun. ‘Seasons In The Sun’ is often heralded as an over sentimental example of bad music, and is ranked among the worst songs of all time – and it is true to say that the English translation removes Brel’s witty, thoughtful and touching lyrics and exchanges them for dreary and reductive couplets that pale in comparison to the original.

For all of its misgivings, it did introduce Brel’s music to a wider audience – and for this it should be applauded. The song would also become the last UK number one single of the 20th century, when covered by the pop boyband Westlife.

Next up is the tangled and seemingly structureless ‘Vivre Debout’ (‘Living Standing Up’ or ‘Living To The Full’), which opens with Brel singing a cappella about being unable to stand up for himself. The lyrics paint a picture of a narrator who “hides in new loves” in order to protect himself from addressing his own insecurities. Brel is accompanied by two classical guitars, and an acoustic bass during the song – the bass picking out the bars while one acoustic guitar roughly strums the chords and the other solos. Castanets punctuate certain parts of the song. The song has an impromptu feel to it, and is built around Brel’s poetic words with a free-form chord structure and rhythm.

‘On N’Oublie Rien’ (‘We Forget Nothing’), in comparison, as a traditionally structured song which brings the record back into focus after the existential crisis of ‘Vivre Debout’. The lyrics depict a narrator who is attempting to forget moments from the past that he has come to regret, yet has come to the conclusion that he must deal with these memories as it’s impossible to remove them from his mind. When following the rambling ‘Vivre Debout’, this song comes across as regimented and stiff, somewhat anchoring the record to reality. An interesting feature of this song is present in its last few bars – the chords shift up and down a tone in a disorienting and surprising way. This sounds to me if it was an effect added in the editing stage by changing the pitch of the recording – which if confirmed would make the recording groundbreaking in terms of its experimental production on a pop album.

After ‘On N’Oublie Rien’ comes ‘Clara’, another foray into Latin American rhythms. The time signature of this track is 5/4 – which is unfamiliar to Western audiences and gives the song a disjointed edge which compliments the lyrics which focus on the narrator’s fixation with ‘Clara’, a dancer in Rio Carnival. The narrator’s love isn’t reciprocated, however, and he sings of how he “died in Paris, a long time ago”, feeling bruised by rejection.

In ‘Le Prochain Amour’ (‘The Next Love’), Brel sings of being defeated by the prospect of starting a new relationship that he knows is doomed to fail just as his previous loves have. Although the love “won’t survive until next summer”, the narrator expresses a presumptuous regret that the lover will hold him back, just as “ponds put rivers in prisons”. The version of this song included on No. 5 is one of three studio versions, and is inferior to the EP version, but superior to the version recorded for 1972’s Ne Me Quitte Pas. The EP version has an entirely different arrangement, including a clarinet-led opening and as the song progresses, Brel is accompanied by spectacular piano embellishments from Gerard Jouannest, as well as a surging brass section which counters the song’s melody by adding dramatic and intense chords into the songs final verse.

‘L’Ivrogne’, like a number of songs on this album, begins with Brel’s unaccompanied voice – which helps to build anticipation before the song itself begins. Here, Brel sings to his “friend” the barman as he drowns his sorrows after a breakup – trying to hide his disappointment at rejection through toasting to all the young women that he still has a chance of loving, calling his former partner a “whore”, before concluding that he needs to drink “night after night” because he’s too ugly for unrequited love. The inclusion of the name “Sylvie” is a reference to the novel of the same name by Gérard de Nerval, who killed himself shortly after it was published. There are two versions of this song too, with the first edition of the album containing a version of the song which doesn’t fade out at the end. There original, unfaded version can also be found on the No. 11 EP.

‘Les Prenoms De Paris’ is a eulogy for the city, which begins with the optimism of a tourist who is imagining Paris as the city of love – but as the song progresses, in the final stanza, the narrator realises that the city is “All grey… full of tears… finished,” because he had seen Paris as a metaphor for love, but had (like many tourists visiting the city) been disappointed.

The album closes with ‘Les Singes’ (‘The Apes’), a highly political and humorous attack on the notion of civility that Brel feels has been misapplied to humans. Opening with percussive noises and the sound of monkey, the song contemplates life before humans became ‘civilised’ as an idilic and struggle-free time when “the flower and the bird were free” and “bananas could be grown even during lent.” The “Apes” Brel refers to are humans, and Brel sings from a third person perspective – condemning mankind’s dominion over the animals.

As the song speeds up (moving from circa 115bpm to 160bpm), the pitch increases, and momentum is gained through the use of brass and piano. The lyrics take a sinister turn in the final stanza, and instead of the tongue-in-cheek lyrics we have grown accustomed to, Brel voice becomes frantic as he lists mans’ atrocities: instruments of torture, Nazi gas chambers, the electric chair, napalm, and the atomic bomb. By the end of the song, Brel is shouting at the top of his lungs as he is engulfed by the trumpets and drums of the track, which disappears with a crescendo of horns. An alternative version of this song can be found on the Suivre L’Etoile box set, which features a very different arrangement. The version on the original album is superior to this alternative take.

Tracks

Click on the song titles to view more information including poetic translations of the piece.

Side one:

- ‘Marieke’

- ‘Le Moribond’ (‘The Dying Man’)

- ‘Vivre Debout’ (‘Life Standing Up’ or ‘Life, To The Full’)

- ‘On N’Oublie Rien’ (‘We Forget Nothing’)

- ‘Clara’

Side two:

- ‘Le Prochain Amour’ (‘The Next Love’)

- ‘L’Ivrogne’ (‘The Drunk’)

- ‘Les Prenoms De Paris’ (‘The First Names Of Paris’)

- ‘Les Singes’ (‘The Apes’)