Looking for Utopia – Guided by Evolution?

The Case of the Fabians (chapter in Mary Kemperink & Leonieke Vermeer, Utopianism and the Sciences, Peeters, Leuven-Paris-Walpole, 2010)

Synopsis

Both Bernard Shaw and his co-Fabian H.G. Wells were deeply influenced by the theory of evolution, and they struggled to come to terms with the philosophical and socio-political consequences of Darwin’s theory. Several other prominent Fabians (like Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Graham Wallas, and David Ritchie) derived much of their inspiration from the legacies of Lamarck, Darwin, and Wallace. Fabianism is often seen as an evolutionary form of socialism, meaning that it took evolutionary science as its model to come to a science-based socialism, gradually. In its most unproblematic form, this line of thinking amounted to the conviction that social evolution would, all by itself, lead to a socialist (or ‘collectivist’) society, sooner or later. But this simple view hardly convinced anybody. Shaw wrote in his introduction to Man and Superman: ‘Progress can do nothing but make the most of us all as we are, and that most would clearly not be enough.’ Or, as he put it more graphically, one simply couldn’t ‘make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear’. Therefore Shaw in his play (which he designed to be ‘a drama of ideas’) put a radical notion centre stage: ‘We must replace the man by the superman.’

Both Bernard Shaw and his co-Fabian H.G. Wells were deeply influenced by the theory of evolution, and they struggled to come to terms with the philosophical and socio-political consequences of Darwin’s theory. Several other prominent Fabians (like Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Graham Wallas, and David Ritchie) derived much of their inspiration from the legacies of Lamarck, Darwin, and Wallace. Fabianism is often seen as an evolutionary form of socialism, meaning that it took evolutionary science as its model to come to a science-based socialism, gradually. In its most unproblematic form, this line of thinking amounted to the conviction that social evolution would, all by itself, lead to a socialist (or ‘collectivist’) society, sooner or later. But this simple view hardly convinced anybody. Shaw wrote in his introduction to Man and Superman: ‘Progress can do nothing but make the most of us all as we are, and that most would clearly not be enough.’ Or, as he put it more graphically, one simply couldn’t ‘make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear’. Therefore Shaw in his play (which he designed to be ‘a drama of ideas’) put a radical notion centre stage: ‘We must replace the man by the superman.’

Shaw made extensive use of Henri Bergson’s concept of ‘creative evolution’, though he preferred the expression ‘the Life Force’. He firmly believed that evolution was not the blind, accidental and destructive process of natural selection that Darwin had presented in such great detail. Shaw’s ‘Superman Utopia’ is evolutionary in a rather particular way. Every present-day Darwinian will immediately notice that Shaw’s view of evolution is both teleological and metaphysical. Evolution had a soul, he felt; it was the conscious self-development of life to ever higher forms. He made no secret of his sympathies for the Lamarckian view that characteristics acquired during a lifetime (the things we learn) were inherited by the next generation.

What Shaw was really interested in was not evolutionary theory as such, but the possibilities to use evolution as the basis for a new religion and a new public morality. He thought a ‘religion of evolution’ could be inspiring and would support an evolutionary ethics. Natural selection, with its ‘mechanical rationalism’ that was the product of the restricted minds of ‘microscope men’ and ‘vivisectors’, would only lead to ‘cynical pessimism, despair and Schrecklichkeit’.

Shaw liked to see himself as a ‘Life Worshipper’, in the line of Wagner and Nietzsche. What his evolutionary religion worshipped was not only the rather abstract Life Force (or universal will to live), but also the much more concrete health and strength of the human race. To his hero Don Juan ‘breeding the race’ was the ‘great central purpose’ and he hoped to breed it ‘to heights now deemed superhuman’. Shaw, like H.G. Wells and other Fabians, wanted to reform the moral rules on marriage and reproduction. In the end Man and Superman turned out to be what, by the sound of its title, it had seemed to be all along: one more example of that most powerful utopian idea of the period, eugenics. The animal origins had to be bred out of the human race, thereby making man ‘bodiless’, meaning that he would no longer be the slave of the animal-like body that encapsulated his mind.

He was a eugenicist, telling us that the lowest of men (the ‘Yahoo’) should be kept from reproducing, while the noblest of men (like Don Juan) should be allowed to breed more freely than the bonds of marriage allowed. This amounted to a proposal to introduce or allow selective breeding, or artificial selection, in order to correct or speed up natural selection.

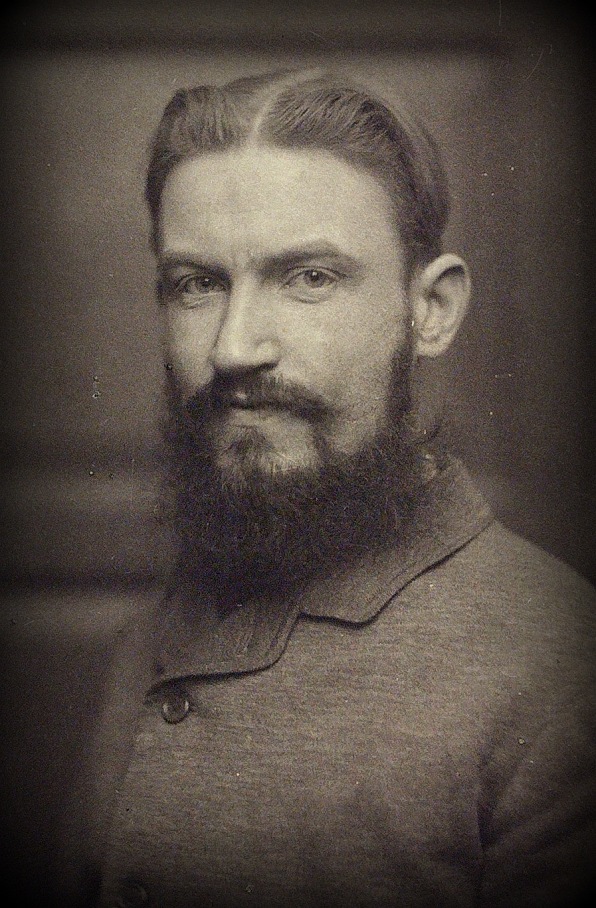

Bernard Shaw

In the first years of the twentieth century H.G. Wells published several non-fictions books, which he liked to refer to as his ‘sociological essays’: Anticipations (1901), Mankind in the Making (1903) and A Modern Utopia (1905). In this last book he stated that evoking a traditional Utopia (a perfect state, static and peaceful) had become useless after Darwin, who had demonstrated that humanity simply could not escape – not even within the perfect utopian state – from the restless forces of natural evolution. A ‘modern’ (post-Darwinian) Utopia was only possible if it were situated on a different planet that found itself in an earlier phase of evolution. One could suppose that, if humans really had the possibility to build up a parallel world on such a planet, they would use the freedom of choice that evolution leaves them in another – and better – way. And this is exactly how Wells laid out his modern Utopia: as a ‘planet beyond Sirius’, where every species of plant or animal life, every human race, every city and every individual human being of the Earth had an ‘Utopian parallel’.

Wells’ real obsession was the future biological quality of the race. It was an obsession he shared with Shaw and that even touched the balanced mind of Beatrice Webb when she called the subject of human breeding (‘this breeding of the right sort of man’) ‘the most important of all questions’. Wells criticised the ‘old’ Utopia’s for disregarding the importance of ‘reproductive competition’ and ‘the hand of selection’. In earnest Wells stated: ‘… it is our business to ask what Utopia will do with its congenital invalids, its idiots and madmen, its drunkards and men of vicious mind, its cruel and furtive souls, its stupid people, too stupid to be of use to the community, its lumpish, unteachable and unimaginative people?’ And his answer was: ‘… the species must be engaged in eliminating them’ and in assuring that the ‘better sort of people’ would have ‘the fullest opportunity of parentage.’

Eugenics could not only prevent the unfit to procreate, it could also encourage ‘the multiplication of exceptionally superior people’. Then it would become possible that ‘men will rise to be over-men’. In Mankind in the Making, where these quotes are taken from, Wells said he thought the combination of negative and positive eugenics was the only real and permanent way of mending the ills of the world. However, he had to admit that it was not at all clear what human characteristics to breed for which ones ‘to breed out’. What was most important to Wells was a controlled development of man, both as a biological and a mental being. This meant: taking over from natural selection. The present chaos of reproduction was unacceptable to him. It was the task of science to make this control possible. Civilisation introduced artificial arrangements that provided security, liberty, and abundance to an unnatural degree. The natural instincts of humans were still too strong, and the controlling power of their will too weak, resulting in excessive behaviour like eating and drinking too much, making love too much and elaborate, becoming lazy, selfish, and easily distracted.

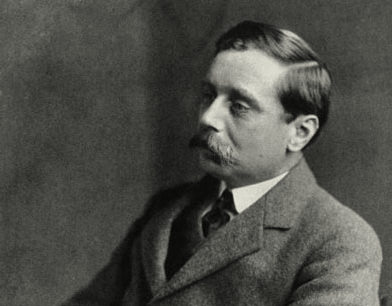

H.G. Wells

In A Modern Utopia introduced a voluntary nobility called the Samurai. They were a special order (an ‘open caste’), which had been composed out of the most energetic, practical, creative and innovative men and women. They had once formed the World State and now directed it: one had to be a Samurai to obtain an important position in government, in education, etc. They were the controlling force in Utopia. They were the ‘New Republicans’ Wells often referred to. One could say the Samurai were Wells’ equivalent to Shaw’s Superman. They all were very healthy, having ‘that clearness of eye that comes with cleanness of blood’. Since a Samurai man was only allowed to marry a Samurai woman, they were also a biological elite. Nevertheless it was stressed by Wells that they were not a hereditary nobility: everybody who met the criteria could become a member of the order.

The fact that Shaw’s Superman and the Samurai of Wells were presented in literary form may lead to the idea that they were purely fictional concepts. However, many of the socio-biological ideas Shaw put in plays and Wells in his futuristic novels and semi-fictional ‘sociological essays’, became part of Fabianism during the first two or three decades of the twentieth century. This is why, I think, Fabianism is utopian in inspiration. From a strictly Darwinian perspective, evolution could be viewed as a non-utopian, or even anti-utopian, idea as long as we think of evolution in terms of necessity, gradualism, materialism and determinism. The Lamarckian perspective, on the other hand, shows that the idea of evolution does have utopian potential. At a different level, however, Darwinism also seems to have stimulated utopian thought. For those who accepted it, Darwinism brought an end to the concept of divine Creation, which in itself is an anti-utopian idea: if everything in nature is just as God wanted it to be, no human Utopia can exist, unless it accords to divine Providence. Darwinism had a double cutting edge: its naturalistic determinism ruled out both divine Creation and Utopias that tried to escape evolution. But, at the same time, as Darwinian science it opened new vistas of scientific control and scientific creation: what if the new biological knowledge gave us the power to speed up or redirect evolution? Certainly this was a most powerful utopian idea.

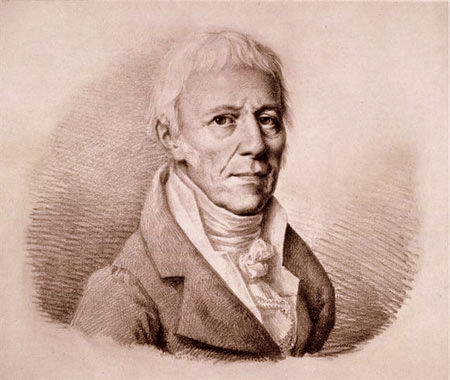

Jean Baptiste Lamarck

Although their Utopias have much in common, the views of Shaw and Wells on evolution differed. Wells had learned all about Darwinism from the first hand: he had been a student of Thomas Huxley, Darwin’s formidable protagonist. Shaw in turn was proud to have developed his own version of evolutionism, synthesising elements of Lamarck, Bergson, and Samuel Butler. He often was rather critical of Darwin and warned Wells not to become ‘the mere amanuensis’ of the neo-Darwinians and ‘mechanists’. Despite his Darwinian training, Wells did not like the philosophic consequences of Darwin’s message either. Like Shaw, he found it difficult to accept that natural selection was a blind process and that the outcome of the struggle to survive depended, at least on the individual level, on chance. The utopian spirit that inspired both Shaw and Wells was, to a large degree, the result of their reaction to the implications of Darwinism.

Shaw’s Don Juan is the very model of a man who, by means of biologically sound promiscuity, delivers more than his fair share in the breeding of a better race. Both Shaw and Wells believed it was necessary to introduce a new marital ethics, allowing the husband who was biologically strong to have sexual relations with other women. They did not want to leave this to chance. What they were thinking of was a socialisation of breeding, making the quality of the race a collective responsibility. This ‘eugenic socialism’ was not new. We can find it in the work of Alfred Russel Wallace. As so many before and after him, Wallace was touched by the fear, common in Social Darwinism, that man living not under natural conditions but in a cultural environment, degenerated. The remedy he saw was ‘human selection’, by which he meant that emancipated woman would wisely select her male partner, excluding by her choice the unfit from the possibility to have children. Eugenics is what connected Wallace with Shaw and Wells and other Fabians, like Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, David Ritchie and Graham Wallas. The power of Darwinism made it impossible for many socialists to believe that it would be enough to ameliorate social conditions. Darwinism made the biological quality of man an indispensable part of social reform. The Fabians often referred to ‘national efficiency’. That could mean many things, but it certainly meant that the fitness and strength of the nation came first.

Shaw and Wells took refuge in utopianism because they knew that outlining a eugenic society, or a eugenic World State, put them outside the then current framework of accepted socio-political opinion. It placed them in the realm of Utopia as it was defined by Karl Mannheim. Typical of the utopian consciousness, Mannheim said, is that it is not ‘in conformity’ (nicht in Deckung) with the actual state of things. Utopian ideas represent a completely different frame of mind that ‘transcends’ current conceptions and practices. As such, Utopias are not just a different way of seeing, explaining, and representing things, like an ideology; it is their objective to give a new direction to the actions of people in order really to create a different state of being. Through their ‘incongruity’, Utopias seek to be a counterforce to the existing historical situation, thereby transforming it. He who presents a Utopia, wants to replace an existing order (Topie) by a new order (Utopie).

What makes the Utopias of Shaw and Wells different from classical utopianism, what makes them modern Utopias? Just posing this question already puts me in opposition to the well-known hypothesis of Sir Isaiah Berlin, who stated that modern western civilisation has seen a decline of utopian ideas. According to Berlin, Utopias are static, they display a static perfection. The creators of Utopias assume that all men have a fixed, unalterable, nature and certain universal, common, immutable goals. In Utopia, this human nature is fully realised and these goals are reached. That is what makes Utopia the perfect society, so perfect to all that it should never change. Painting a picture of Utopia served as a means in the western tradition to measure the extent by which the present world fell short of being perfect.

With Machiavelli, Berlin wrote, started the gradual dismantling of the idea, so crucial to utopianism, of there being but one perfect human nature (as defined by medieval Christianity). In the romantic period, the restless ‘self’ and the creative genius of the individual will were discovered, or rediscovered. This, Berlin said, was the cause of ‘permanent unease, indeed anxiety’, in the European consciousness, up to this day. History and the present human life were now seen as a constant struggle of conflicting wills (of individuals, races or nation-states). This view was incompatible with the idea, so essential to utopianism, that human existence is ‘by nature’ harmonious and that a perfect state of human existence – perfect to all – can be reached. Besides, the rise of nationalism (and of the cult of the nation-state) strongly weakened the idea that universal perfection was feasible or even desirable. Wells recognised the anti-utopian character of nationalism when he gave his ‘modern Utopia’ the form of a World State.

Graham Wallas

His Utopia, just like the Lamarckian vistas of Shaw, shows that there indeed is such a thing as post-romantic utopianism, which, according to the Berlin hypothesis, could only have been a marginal and forceless phenomenon or could not have existed at all. Indeed, even the earlier nineteenth-century Utopias of Saint-Simon and Comte (international cooperative and peaceful industrialism and the ‘Religion of Humanity’) go a long way to prove that romanticism, subjectivism and nationalism did not kill Utopia, as Berlin supposed they did. The Utopias of Shaw and Wells in several ways are truly modern. They are not backward-looking, embracing a previous perfect state as their ideal, but futuristic. They are evolutionary (and therefore dynamic, not static, and more or less science-based). They refer to international government on a European or universal scale, using the possibilities of modern communication and of emerging international organisations that could really develop into alternative centres of political power.

And they are modern, too, in their ambiguity or ambivalence. This means that they are not perfect: there are social divisions in A Modern Utopia, with a ruling elite, which implies inequalities; there are asylums and islands where the imperfect are forced to live in isolation. And, above all, there is a tight social control in Utopia to combat the democratic and capitalistic chaos both Shaw and Wells feared so much. This is where science came in: its contribution would be to control, to put an end to chaos. At this point there is a striking resemblance to Brave New World, Aldous Huxley’s novel that is often called dystopian, but that the author himself thought of as a Utopia. Like Wells (and Shaw) Huxley distrusted modern mass society and parliamentary democracy. Brave New World of course satirises industrial and social planning, but it has been pointed out that there is some ambivalence in the way Huxley talked of stability, control, planning and efficiency: he did not treat them as wholly negative. Like Wells’ Modern Utopia the Brave New World is a World State. Biological engineering is taken to extremes: in a ‘London Hatchery’ millions of standardised citizens are being produced. Huxley associated eugenics with the ‘standardization of the human product’, which was a great help to factory-management, he added sarcastically. There is also an elite in Brave New World, the Alpha-Plus, somewhat resembling the Samurai. Huxley called it a ‘scientific cast system’. The World State has a motto that symbolises its collectivist character: Community, Identity, Stability.

Samurai

How can we explain this ambiguity in the modern Utopias of Wells, Shaw and Huxley? For one, they did not want to choose between the objectivist rationalism and scientism of the Enlightenment on the one hand and the subjectivist and elitist philosophy of the will that dominated the Romantic Age. They probably could not make such a choice: since historical man had lived through both these periods and their ways of seeing and thinking, they both belonged to the cultural heritage that shaped the modern Utopia. Making a deliberate choice for the Enlightenment Project or for the Romantic Reaction that followed it, would have made them naive. And that is the one thing modern writers do not want to be accused of; they want to face the full complexity of the historical, social and political reality.

As the inheritors of dialectics and evolutionary struggle on the one hand, and of planning and social engineering on the other, they simply had to take both these sides into consideration. In a world that was divided between the large political and social blocs of Democracy, Fascism and Communism, to think that utopian perfection in the sense of the Berlin hypothesis was still possible, would not only have seemed naive, it would not have accorded very well with the status of avant-garde thinkers that these writers desired. The ambiguity they introduced gave them an alibi for crossing the line of convention in depicting social, political and biological practices that were (to repeat Mannheim’s formula) not in conformity with the actual state of things, but transcended them, introducing a new order of some kind.

Utopianism and the Sciences is available at www.peeters-leuven.be