Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), one of the most famous poets of Japan, was a master of the haiku, a poetic form in which an abundance of meaning is concentrated into a paucity of syllables. Basho travelled widely in Japan, writing about t his experiences in a fascinating mixture of prose and poetry. In 1689 he undertook his longest journey: from Edo into the far north of Japan, a region known as Oku. His record of that journey is known as Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the North).

Life of the Poet

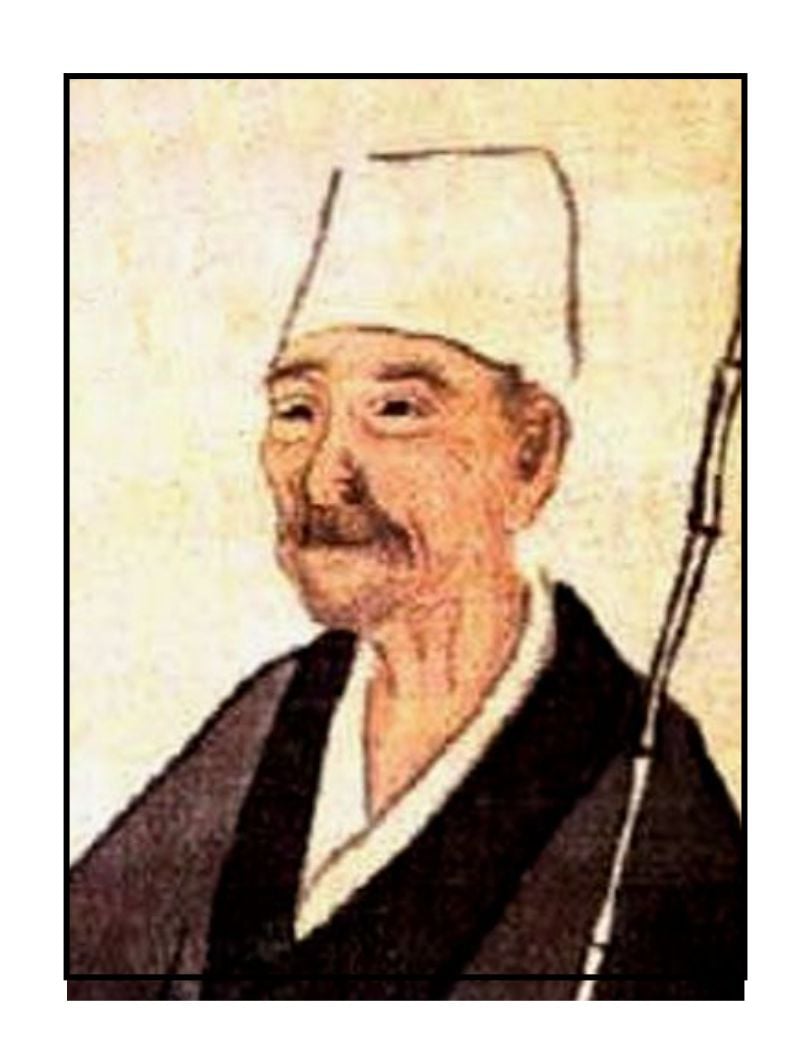

Basho was born in Ueno in 1644 as Matsuo Kinsaku. As a young man, he served Todo Yoshitada, the local Samurai lord, and gained from him a passion for poetry. After the death of his master in 1666, Basho left Ueno. No one knows where he went or what he did for the next few years. Tradition suggests that he studied poetry, philosophy and calligraphy, perhaps in Kyoto (Ueda, 1970). The illustration on the right is a detail from a portrait of Basho by Yosa Buson (1716-1784).

Basho was born in Ueno in 1644 as Matsuo Kinsaku. As a young man, he served Todo Yoshitada, the local Samurai lord, and gained from him a passion for poetry. After the death of his master in 1666, Basho left Ueno. No one knows where he went or what he did for the next few years. Tradition suggests that he studied poetry, philosophy and calligraphy, perhaps in Kyoto (Ueda, 1970). The illustration on the right is a detail from a portrait of Basho by Yosa Buson (1716-1784).

In 1672, he published The Seashell Game, an anthology of haiku by various poets, together with his personal commentary. Later that year Basho moved to Edo (modern Tokyo) as a professional poet, organizing poetry sessions, reviewing the work of others, judging poetry contests, and providing commentaries on classic poems (Carter, 1997).

In 1680 Basho retired to a small hut in a rustic area of Edo. A disciple planted a small Japanese banana tree (Musa basjoo) beside his hut, and the poet henceforth assumed the name Matsuo Basho. The tree typically rises to about 2 meters and has a crown of broad leaves each up to 2 meters in length. These fronds are easily torn by the winds (see illustration on the right). Basho felt that he shared both the sensitivity and the resilience of the tree. The following is a poem by Basho about his tree:

Basho nowaki-shite

tarai ni ame o

kiku yo kana

The banana tree is blasted in the storm,

I listen all night to the leaking

raindrops in a basin

(trans. Toshiharu Oseko, 1990)

The alliteration of the k-sounds at the end of the poem suggests the recurring drops from the leaking roof.

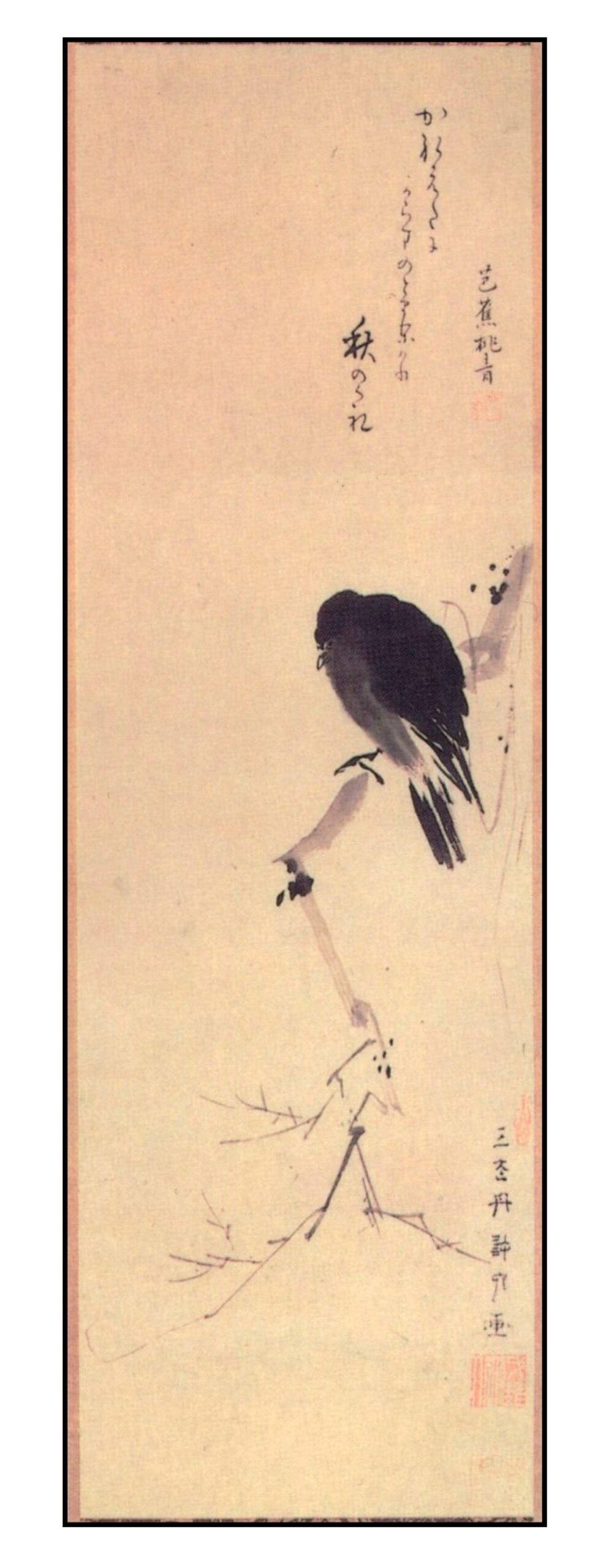

In his new home, Basho practiced Zen Buddhism with the monk Butcho, who lived nearby, and studied painting with another neighbor, Morikawa Kyoriku (1656-1715). He lived by himself, likening himself to a crow on a bare branch (Carter, 1997). On the right is a painting by Morikawa Kyoriku with calligraphy by Basho. Both artists celebrate the poet’s newfound solitude.

kare eda ni

karasu no tomarikeri

aki no kure

On a bare branch

a crow settled down

autumn evening

(trans. Jane Reichhold, 2008)

Basho soon began to travel through the different regions of Japan, recording his journeys in prose and poetry. Most of the poems were in the haiku format.

The Evolution of Haiku

Medieval Japanese poetry (waka) was largely based on a 31-syllable format consisting of 5 sections of 5-7-5-7-7 syllables. By themselves these lines could be a tanka poem. Linking together many sections was the basis of renga poetry (Carter, 1991; Ueda 1991). A single poet could write a long renga by himself, or several poets could get together to create the succeeding sections of the poem. In the 16th Century a style of haikai no renga evolved, using common and often comic subjects, light-hearted puns and rhymes. As a professional poet, Basho would have arranged renga sessions wherein different poets would interact, one proposing a hokku of 5-7-5 syllables and the next capping this with the waki of 7-7 syllables. After 1680 Basho isolated the initial hokku, and imbued it with greater seriousness. In later years this format became known as haiku.

A haiku is characterized by its 5-7-5 syllabic structure. In general, a haiku contains two contrasting ideas often separated by a kireji or cutting word. Usually, the haiku contains some reference to the season of the year (kigo).

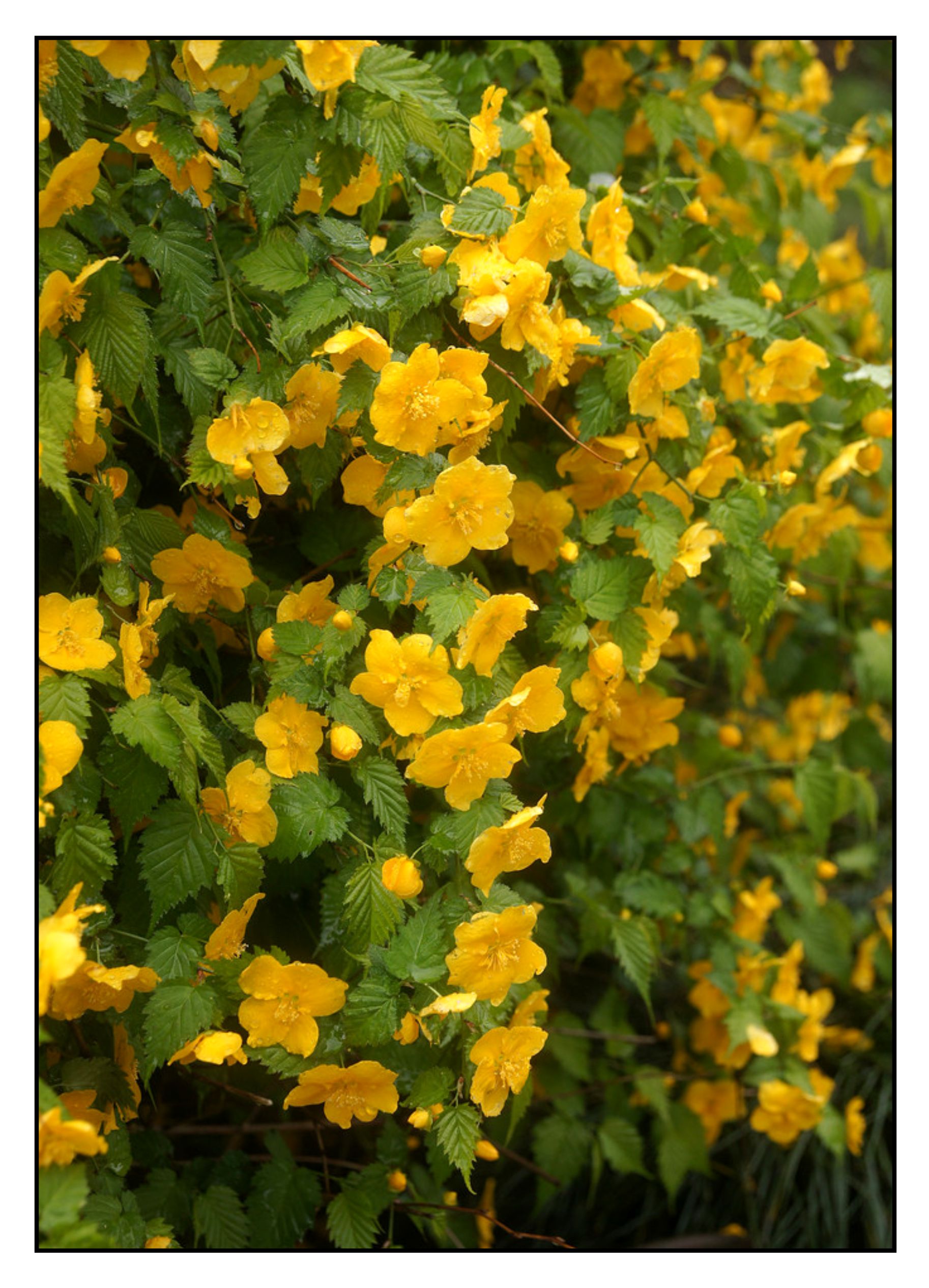

Basho wrote the following haiku after observing the falling yellow petals of Japanese roses (yamabuki) close to a waterfall near Yoshino Mountain south of Kyoto. The flowers are illustrated on the left. The painting below is once again by Morikawa Kyoriku and the calligraphy by Basho. The cursive calligraphy is beautiful but only interpretable by experts.

horo horo to

yamabuki chiru ka

taki no oto

quietly quietly petal by petal

yellow mountain roses fall kerria roses at fall

sound of the rapids the sounding waters

(trans. Makoto Ueda, 1991) (trans. Andrew Fitzsimons, 2022)

Toshiharu Oseko provides the following translation and notes:

In quiet succession,

The yellow flowers of Kerria fall

To the sound of the waterfall

horo-horo-to: an onomatopoeic word (adv.) describing flower-petals are falling down quietly here and there in succession. This word has a delicate poetic sound exactly matched with this scene even with the visual image so vivid

yamabuki: a Japanese rose, Kerria japonica

chiru: to fall

ka: an exclamatory particle

taki: a waterfall

oto: a sound

The cutting word is the particle ka. The seasonal reference is to the late spring time when the yamabuki blossoms fall.

Translating haiku can follow different principles. One can maintain the same syllabic structure (as in the Fitzsimons translation), but this is often difficult. Furthermore, the translator must choose between providing as much context as possible (as in the Oseko version) or being as concise as the original (as in the Ueda version).

This poem has evoked extensive commentary (Ueda, 1991). The following is from Handa:

As the poet trod a shady path by the river, he saw petals of mountain roses fluttering down. That instant he awoke to the sound of the rapids, to which he had paid no attention before. In brief, I wish to interpret the poem as presenting a shift of the senses: the vision of falling petals causing the poet to shift his awareness to the sound of the rapids.

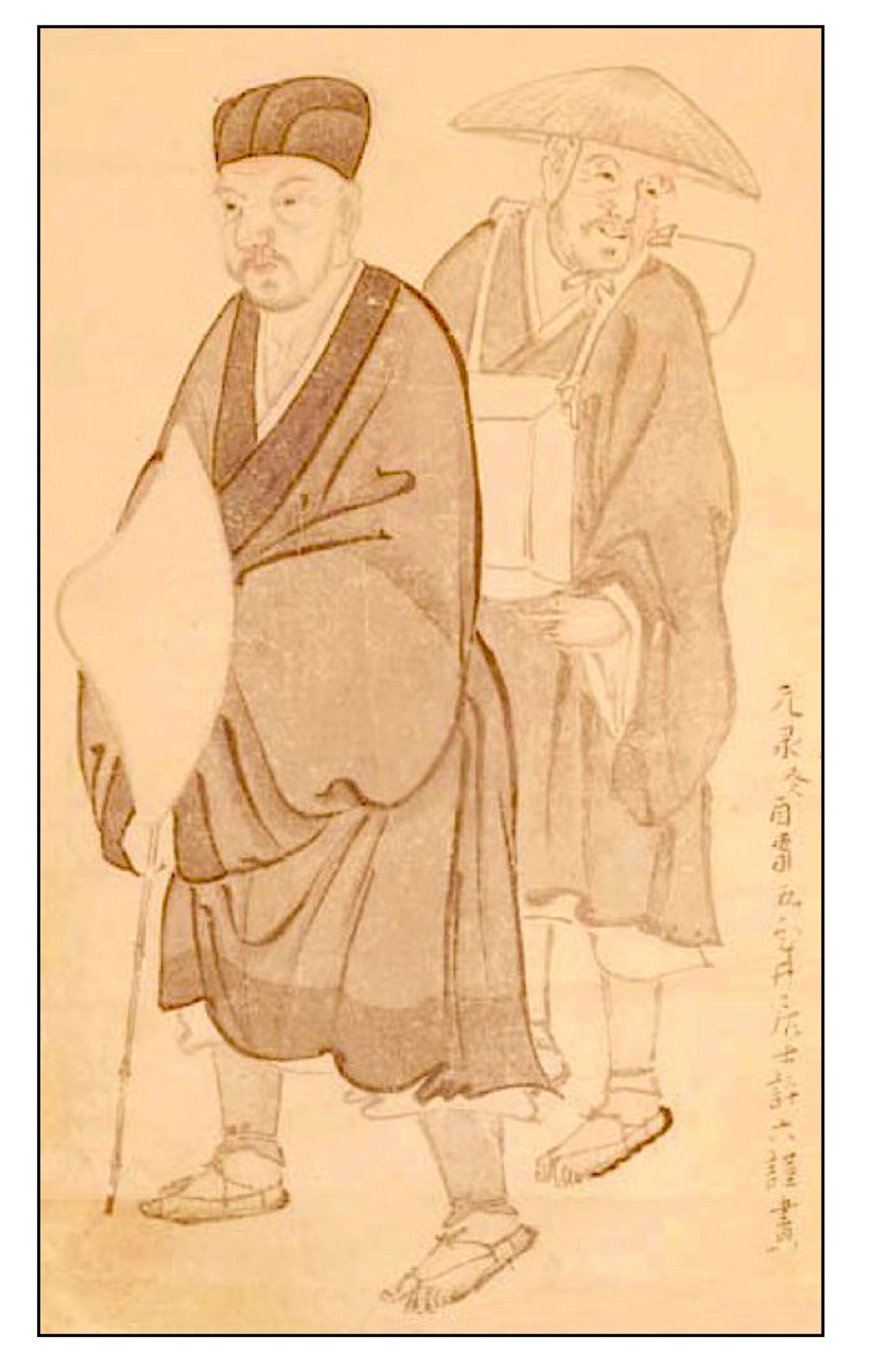

The Lure of Oku

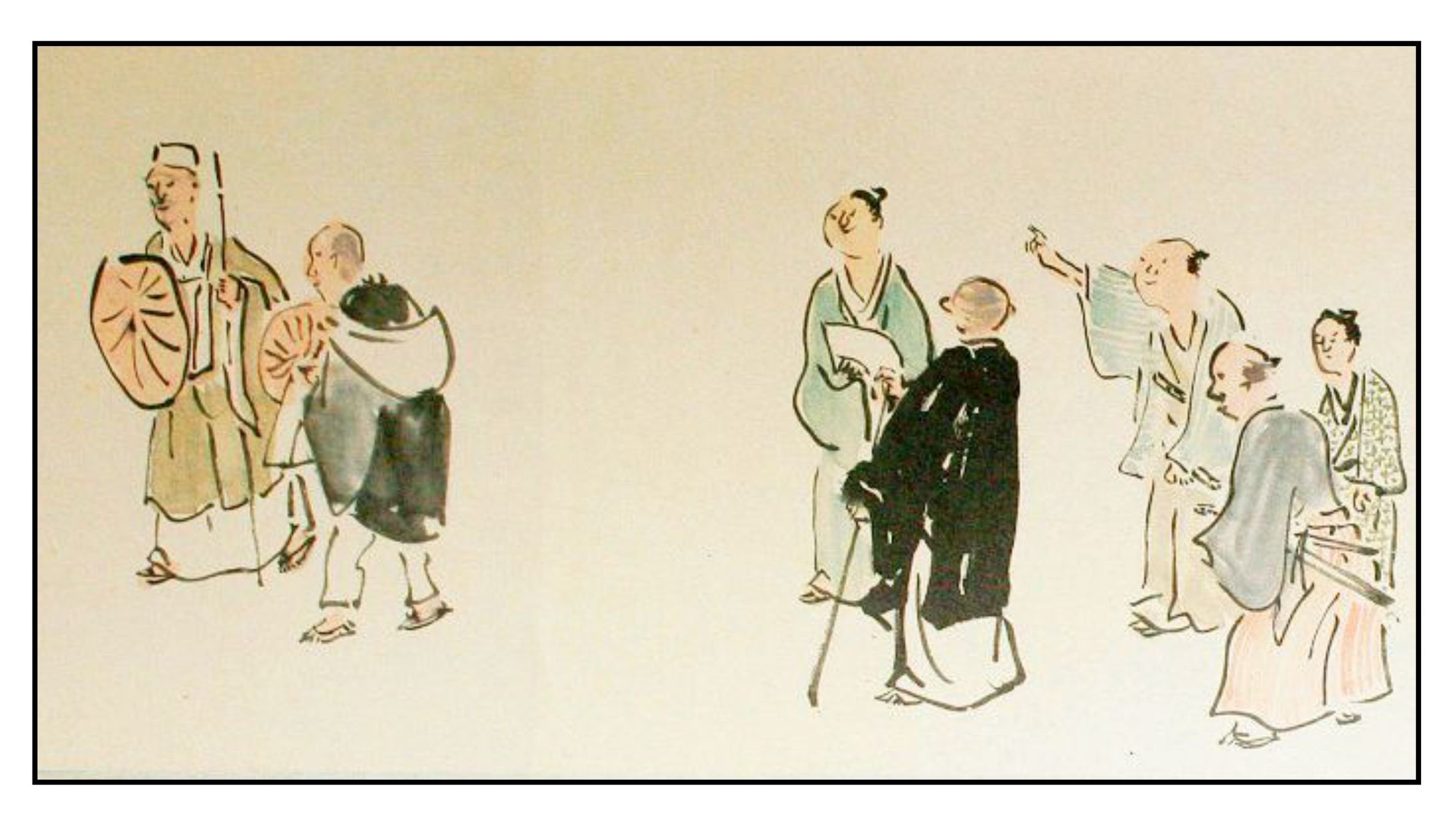

From 1882 until the end of his life, Basho travelled to various regions to Japan, hoping to find himself in what he saw, and to describe what he found in poetry. Beginning in the spring of 1689 he undertook a journey to Oku, the northern regions of Japan, together with his companion Sora. They covered a distance of some 1500 miles over a period of 156 days, almost all of it on foot. The painting on the right by Morikawa Kyoriku shows Basho and Sora as they set out on their journey.

Basho published a record of his journey in Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to Oku). The word Oku has been variously translated as: the north, the deep north, the interior, the hinterland, and the heart. Keene (1996) remarks that Oku was

the general name for the provinces at the northern end of the island of Honshu. Oku also means “interior” or “inner recesses,” and this meaning would also be appropriate, both geographically, indicating that Basho’s travels would take him to the inner recesses of the country, and metaphorically, suggesting that his journey was to an inner world, probably the world of haiku poetry. We shall never know which of these meanings Basho intended; perhaps he meant all of them.

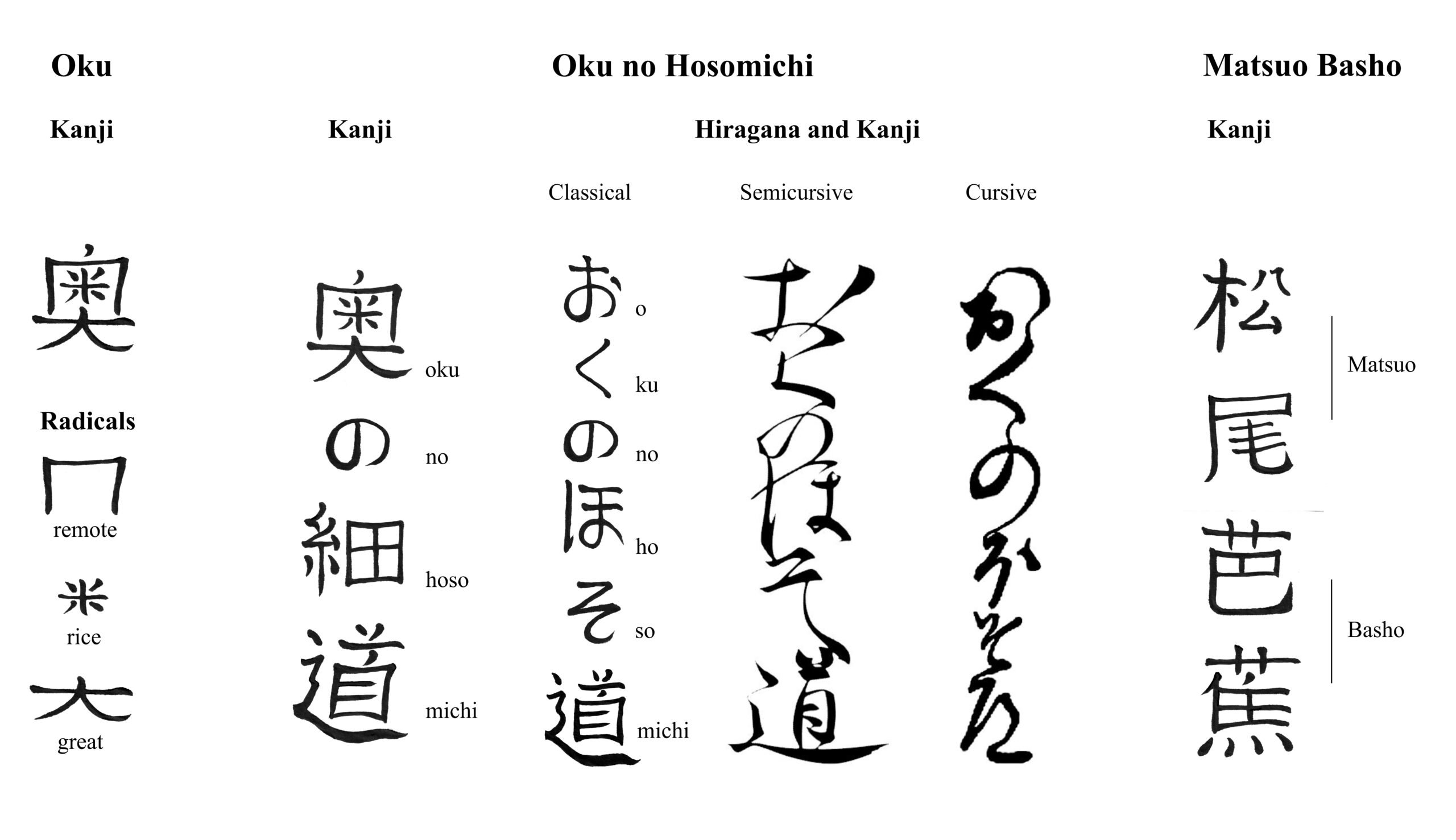

Japanese is typically written using both ideographs (kanji) and a syllabic alphabet (hiragana). The following illustration shows the kanji for oku on the left. It contains the radicals for “remote,” “rice,” and “great.” Since this kanji is uncommon, the title of the book is typically written using hiragana script, except for the final term michi (road, path), which is expressed in kanji. This ideograph for michi is the same as that for do (way, teaching), which derives from the Chinese dao, the way of Daoism. A brief discussion of the differentiation of michi and do is available on the web. The latter is used in words that describe the study of judo (gentle way) or shado (calligraphy). Basho was clearly aware of the two meanings of the kanji. The illustration also shows the title in full kanji, and in semi-cursive (Miyata Masayaki) and cursive (unknown calligrapher) scripts. On the right are the kanji for Matsuo Basho.

The following illustration shows a map of the central part of Japan with an outline of Basho’s journey, beginning in Edo and ending in Ogaki.

The painting below is by Yusa Buson (1716-1784), a painter and haiku poet, who produced a illustrated copy of Basho’s Oku no Hosomichi. It shows Basho and Sora taking leave of their friends as they set out on their journey.

Days and Months

Basho began Oku no Hosomichi with a brief comment on the passage of time and his need to travel:

Days and months are travellers of eternity. So are the years that-pass by. Those who steer a boat across the sea, or drive a horse over the earth till they succumb to the weight of years, spend every minute of their lives travelling. There are a great number of ancients, too, who died on the road. I myself have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind — filled with a strong desire to wander. (translated by Noboyuki Yuasa, 1966)

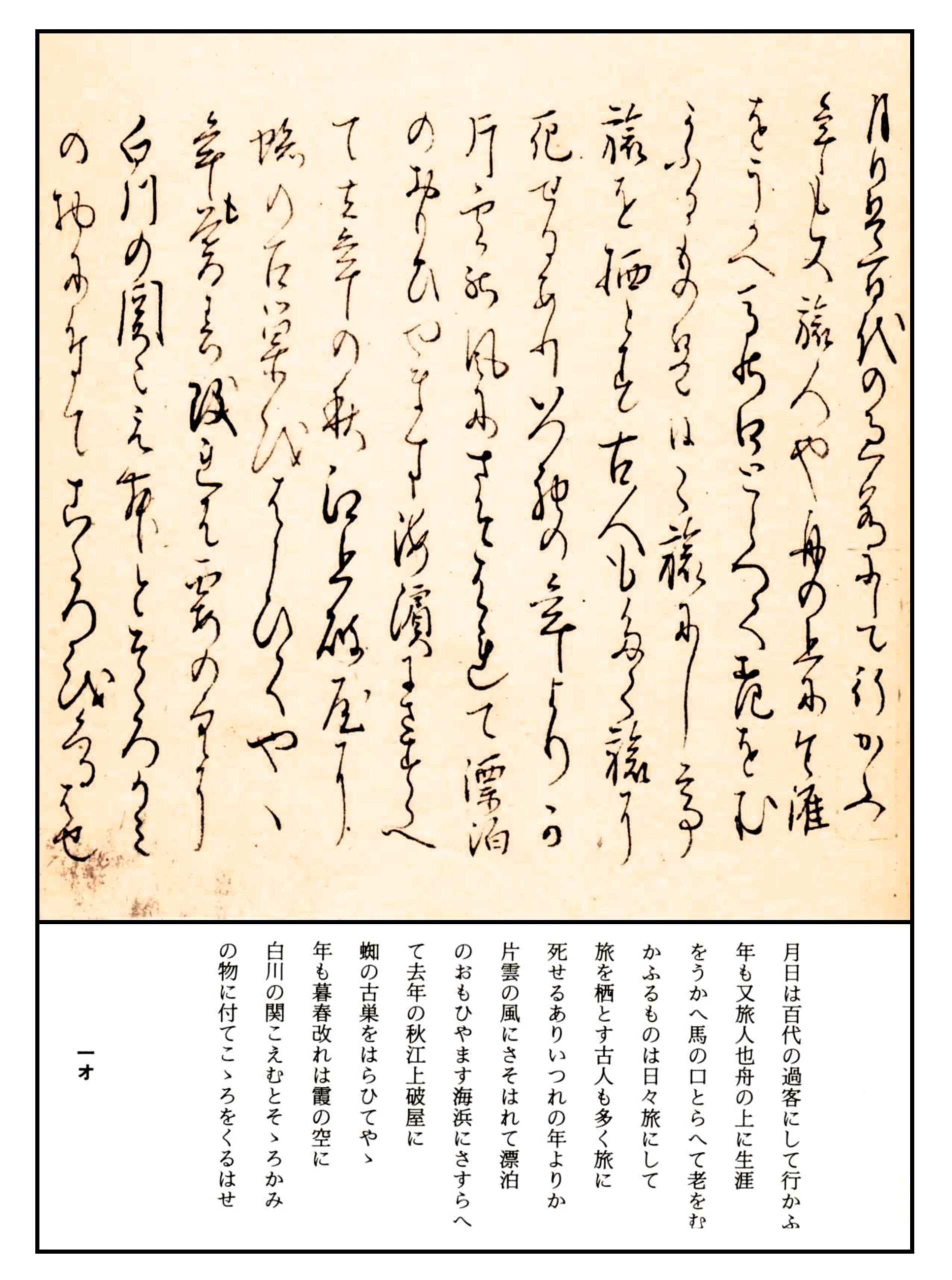

The following illustration shows the beginning of the book in Basho’s own calligraphy, from a scroll that was discovered in 1996. The text is read from top to bottom and from right to left.

The initial characters of the book can be translated as the “sun” and the “moon” instead of “days” and “months.” Ideographs are intrinsically metaphorical. Another translation of the opening lines is therefore:

The moon and sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on. A lifetime adrift in a boat, or in old age leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home. From the earliest times there have always been some who perished along the road. Still I have always been drawn by wind-blown clouds into dreams of a lifetime of wandering. (Hamill, 1998)

The opening words of the book allude to a poem by the 8th-Century Chinese poet Li Bai which states that the “sun and moon are wayfarers down the generations” (Carter 2020, p 97). Basho was as much a wanderer as Li Bai, who spent much of his life in exile in the hinterland of China.

Willow Trees

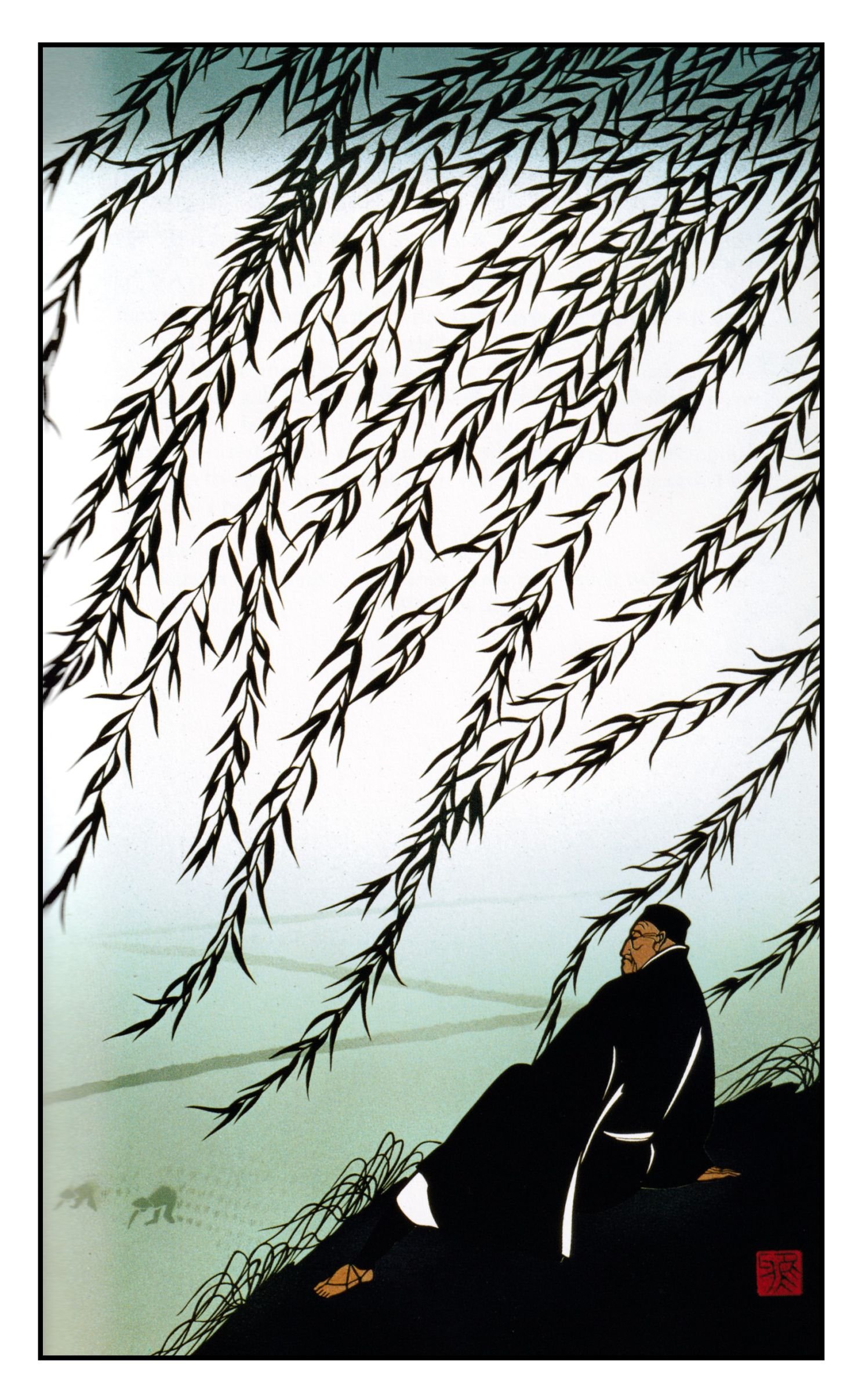

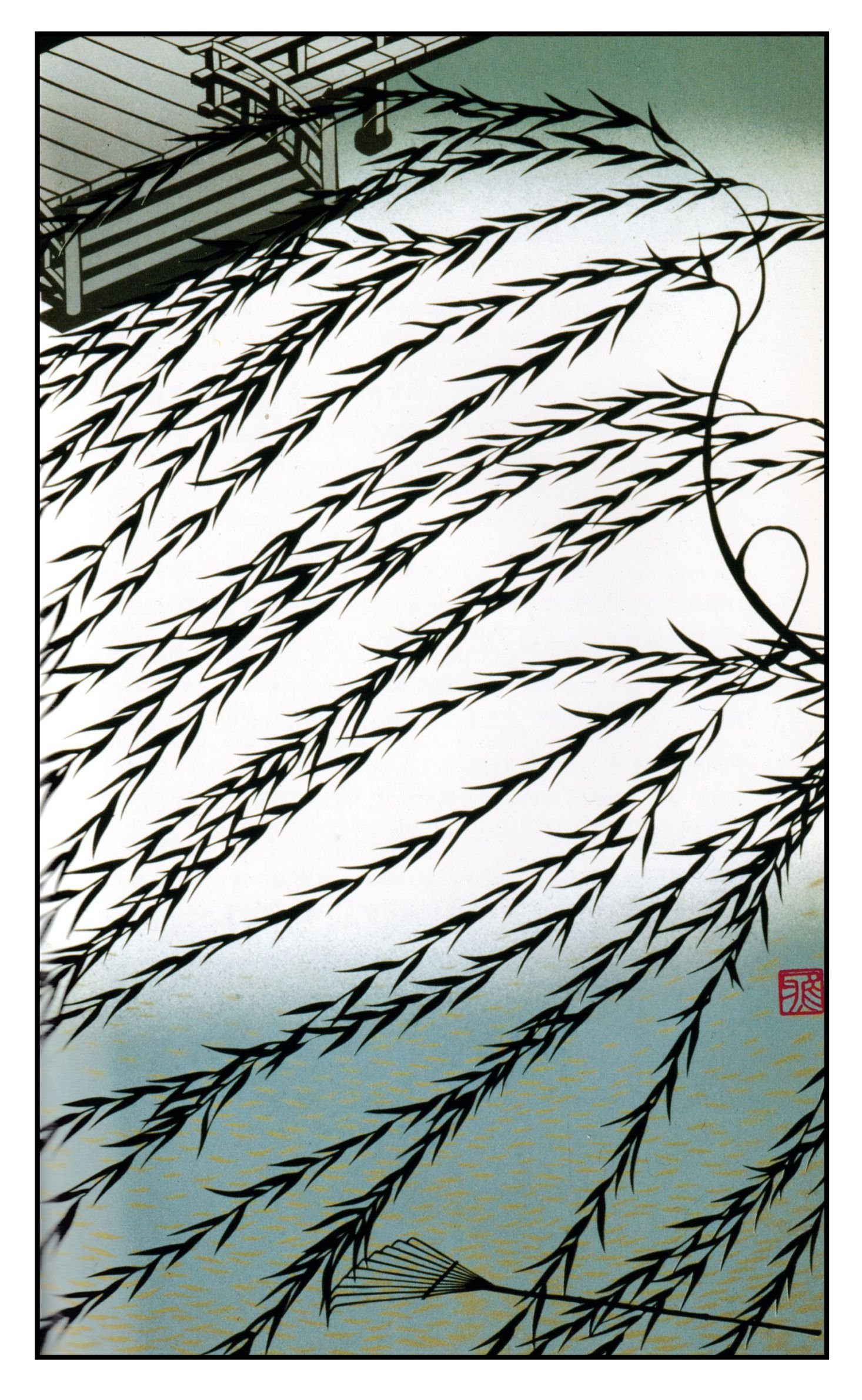

Basho visited briefly the great Tokugawa monuments in Nikko, but was more concerned with simpler things. Near Ashino, Basho stopped by a willow tree (yanagi) that had been made famous by the 12th-Century Japanese poet Saigyo. Basho sat for the whole day beneath the willow branches, watching as the peasants planted rice in a paddy field. The illustration is by Miyata Masayuki:

ta ichimai

uete tachisaru

yanagi kana

They sowed a whole field

and only then did I leave

Saigyo’s willow tree

(trans. Donald Keene, 1996)

Near the end of his trip Basho stayed for a night at a Buddhist temple near Daishoji. In the morning, he swept away the fallen willow leaves before leaving, a small recompense for the monks’ hospitality. Again, the illustration is by Miyata Masayuki:

niwa haki-te

ide-baya tera ni

chiru yanagi

I’ll sweep the garden

before I leave – in the temple

the willow leaves fall

(trans. Donald Keene, 1996)

Matsushima

In the bay of Matsushima are hundreds of small rocky islands topped by weathered pine trees (matsu, pine, and shima, island). Basho was entranced by the view. On the right of the following illustration is a representation of the bay by Miyata Masayuki. On the left are a photograph of one of the islands, and a photograph of me talking to an effigy of Basho outside a tea-house in Matsushima.

Basho described the bay:

And so many islands!—tall ones looming into the heavens, low ones crawling over the waves. Some have two layers, others three; appearing separate from the left, connected to the right. One island carries another on its back, others seem to embrace, like parents or grandparents with their young. The pines are of the richest green, their branches molded by salt spray into natural shapes that seem as if man-made. So fine is the beauty of the scene that one envisions a woman just finished applying her makeup, or a landscape crafted by Oyamazumi [the god of the mountains – yama] in the age of the mighty gods. To capture with the brush the work of Heaven’s creation—why, no one could do it, not with paint, not with words (translation Carter, 2020).

Though Basho was too overcome by Matsushima’s beauty to write a poem, Sora composed:

Matsushima ya

tsuru ni mi wo kare

hototogisu

In Matsushima

you’ll need the wings of a crane

little cuckoo

(trans. Sam Hamill, 1998)

The poem is cryptic: the idea is that the tiny cuckoo would need to borrow the huge wings of the crane to comprehend the beauty of the scene.

Basho later wrote a poem about Matsushima though this was not included in Oku no Hosomichi.

shimajima ya

chiji ni kudakite

natsu no umi

Islands and islands

a thousand pieces shattered

on the summer sea

(trans. Andrew Fitzsimons, 2022)

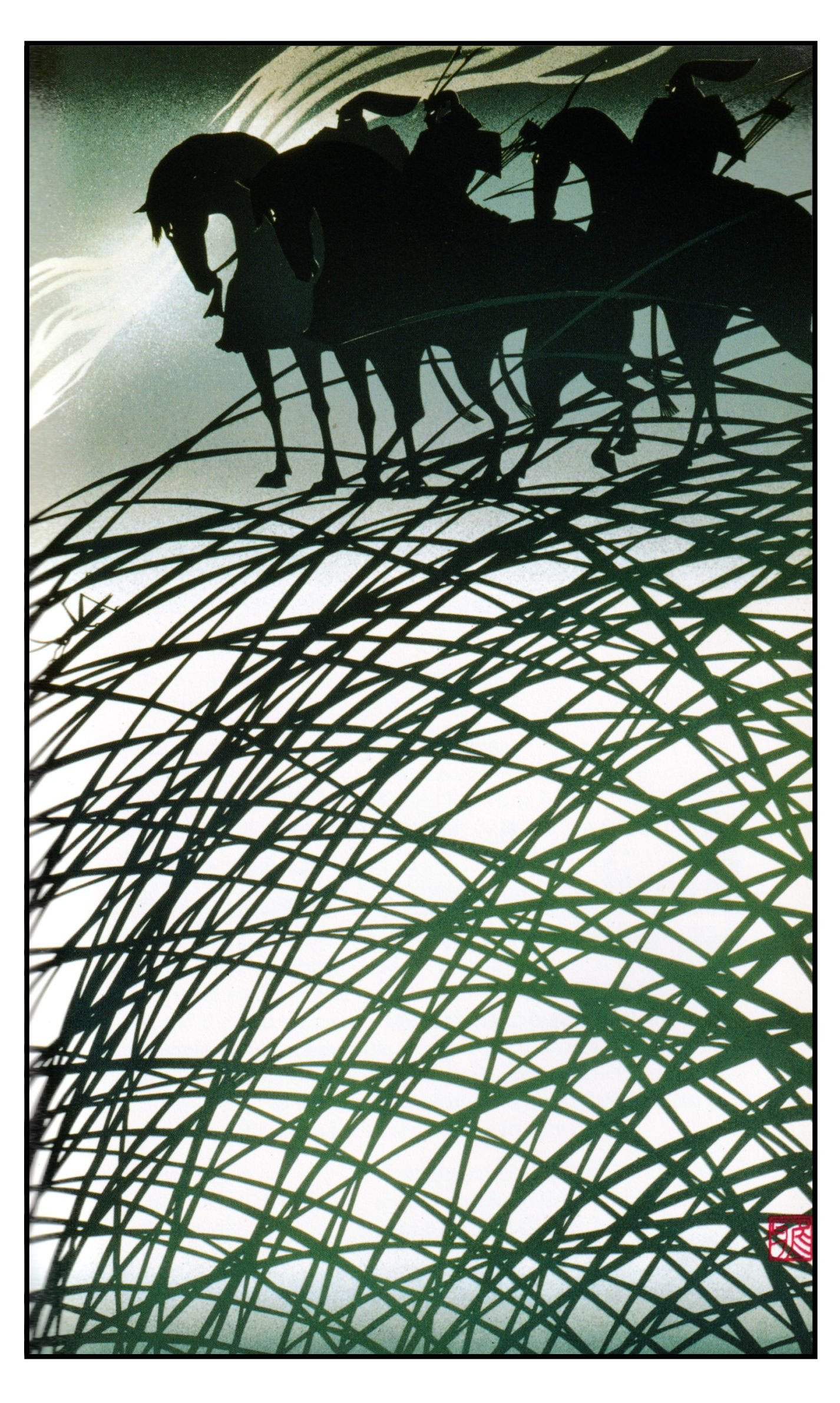

Hiraizumi

From Matsushima, Basho journeyed north to the site where Minamoto no Yoshitsune, the great Samurai warrior, had been defeated in 1189 CE by the army of his brother. Yoshitsune retired to the castle of Koromogawa to commit seppuku (ritual suicide). Outside on the bridge, his companion Benkei prevented his enemies from interfering. After failing to best him in single-handed combat, the attackers killed him with arrows. Benkei died but his body remained standing, and it was a long time before anyone could gather enough courage to cross the bridge. The castle was razed to the ground: nothing remains.

Basho remembered a poem of the 8th-Century Chinese poet Du Fu who wrote a poem entitled Spring View about the wars and rebellions of his day. It begins:

The country ravaged, mountains and rivers remain

in spring at the fortress, the grasses and bushes grow thick

(translation by Carter, 2020)

Basho composed his haiku in homage to both Yoshitsune and Du Fu. The illustrations on the right is by Miyata Masayuki.

natsukusa ya

tsuwamono-domo ga

yume no ato

Only summer grass grows

Where ancient warriors

Used to dream

(trans. Toshiharu Oseko, 1990)

The following provides a recording of the poem in both Japanese and English. This and all subsequent readings in this post are by Takashi Sudo. The English translation he is using is by Hiroaki Sato (1996).

Fleas and Lice

The accommodations where Basho and Sora stayed were often far from luxurious. At Shitomae the guests and the horses were under one roof:

nomi shirami

uma no shitosuru

makuramoto

Fleas and lice

a horse pissing

next to my pillow

(trans. David Young, 2013)

The word for piss, shito, puns with the place name.

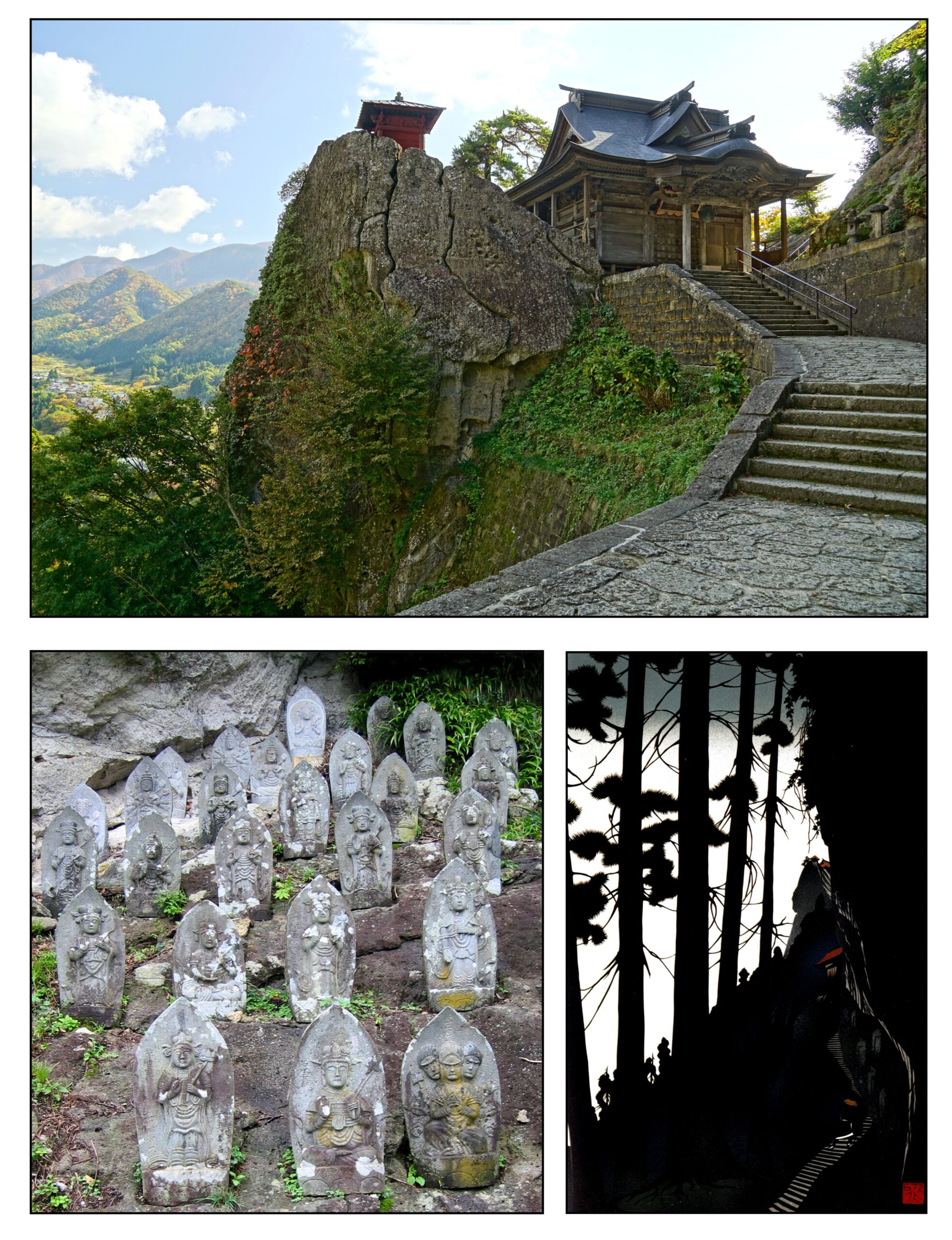

Yamadera

In the middle of summer, Basho visited Ryushakuji, also known as Yamadera (mountain temple). The temples of this Buddhist complex are located on the side of a mountain, linked together by some 1000 stone steps. The mountain is covered with pines and the place is renowned for its tranquility. Basho found that the cry of a cicada intensified the silence.

shizukasa ya

iwa ni shimi-iru

semi no koe

Quietness

seeping into the rocks,

the cicada’s voice

(trans Hiroaki Sato, 1996)

The upper part of the following illustration shows the topmost temple of the complex. Below is a photograph of votive buddhas on the hillside, and an impression of the temple steps by Miyata Masyuki.

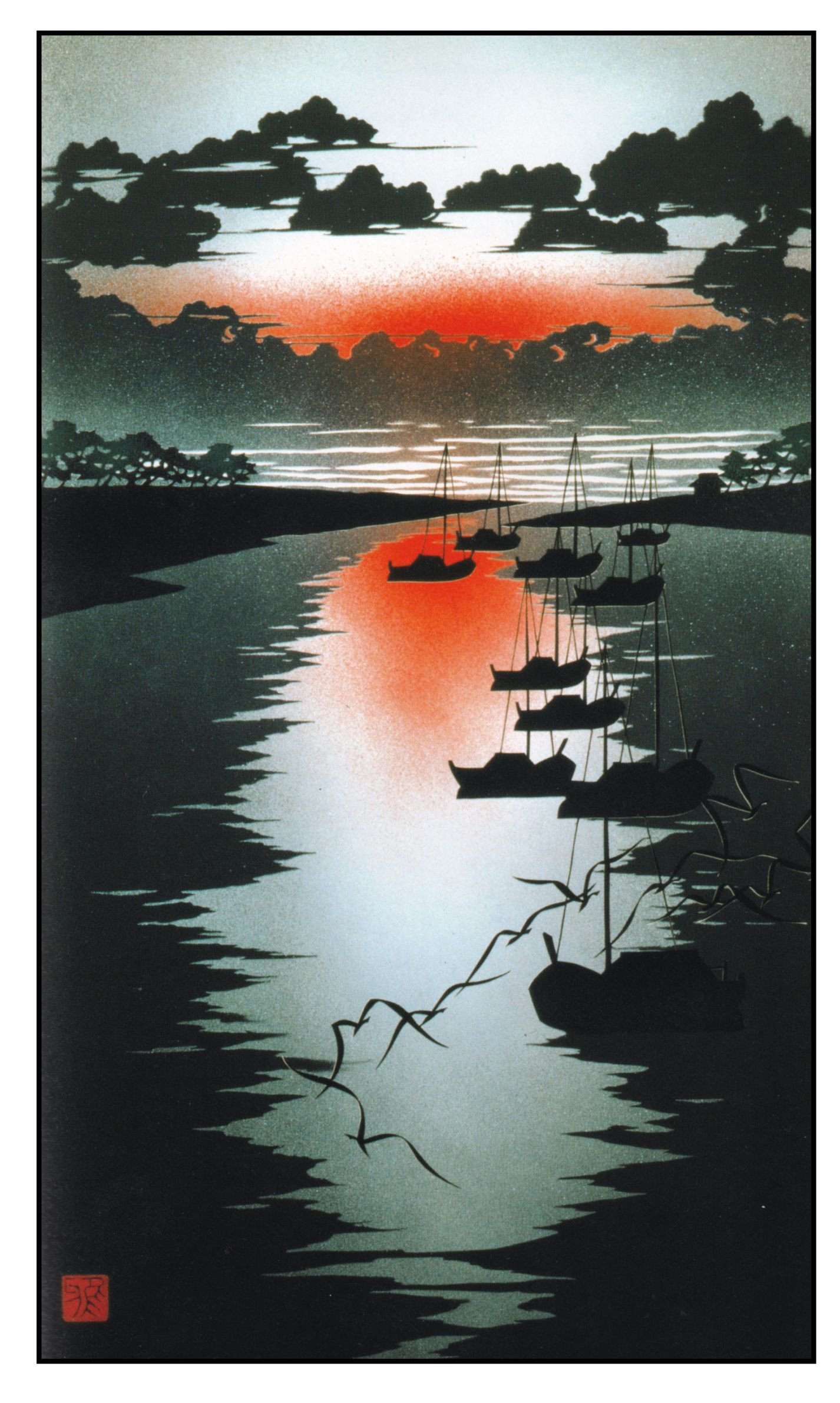

Western Sunset

After spending some time in the region of the Dewa Sanzan (Three Mountains of Dewa), Basho came down to Sagata where the Mogami River empties into the Sea of Japan. The illustration on the right is by Miyata Masayuki>

atsuki hi o

umi ni iretari

Mogamigawa

Pouring the hot sun

into the sea,

the Mogami River

(trans. Hiroaki Sato, 1996)

Sea and Stars

One night near Niigata Basho compared the rough seas with the serenity of the stars:

araumi ya

Sado ni yokotau

Amanogawa

The turbulent sea

unfurling over Sado

the River of Stars

(trans. Andrew Fitzsimons, 2022)

Amanogawa (Heaven’s River) is the Japanese term for the Milky Way.

Bush Clover and Moon

One night in late summer, Basho and Sora spent the night in an inn near Ichiburi. Two prostitutes were staying in an adjacent room. From listening to their conversation, Basho discovered that they had repented of their life and were journeying to the Ise Shrine to seek redemption. He wrote the following haiku:

Hitotsu-ya ni

yujo mo ne-tari

hagi to tsuki.

At the same inn Under the same roof

play women are also sleeping prostitutes are also sleeping

bush clover and the moon bush clover and the moon

(trans. Robert Aiken, 1978) (trans. Toshiharu Oseko, 1990)

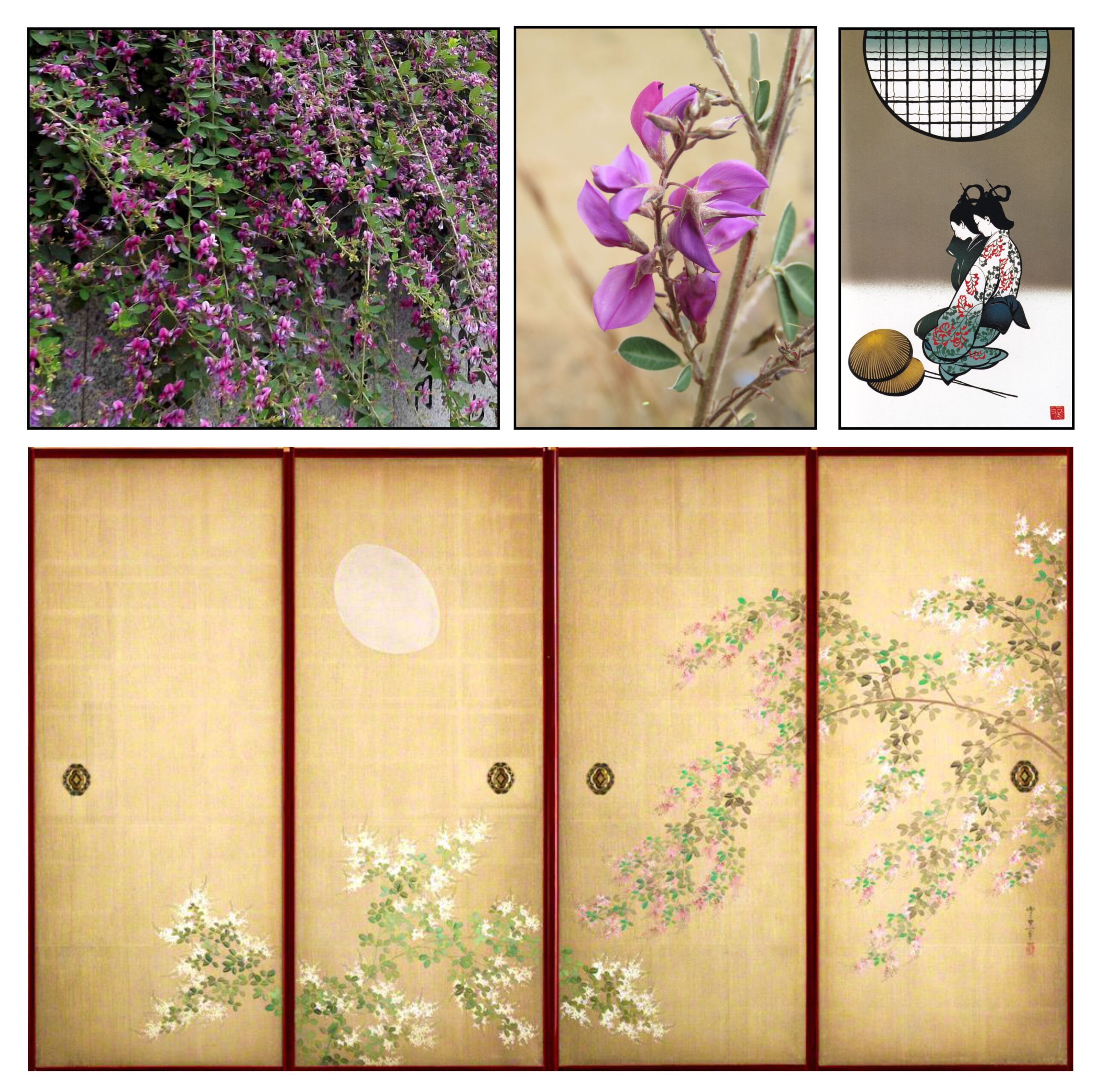

Bush clover (Lespedeza japonica) is a bushy plant with multiple blue-pink flowers on slender branches that trail downward from the center.

Since this is probably the most famous haiku in the book, it is worth considering the notes from Toshiharu Oseko (lightly edited):

hitotsu: one, ya = ie = uchi: a house, ni: in, at

hitotsu-ya ni: (1) under the same roof (2) in a solitary house. The basic meaning in this poem is 1, but it also has a faint image of 2.

yujo: a prostitute

mo: a particle for an addition and stress

ne: from neru, to sleep, lie down, go to bed. This word refers not only to the people, but also to a bush clover indirectly.

-tari: aux. v. for perfect and progressive perfect, but my interpretation is that the women (and probably Sora also) are already sleeping, but Basho is still awake looking at the moon over the bush clover

hagi: a bush clover, Lespedeza. When a bush clover droops down, it is often expressed as neru, lying down. Hence it could be possible to take the bush clover as a euphemistic metaphor of a prostitute.

The upper left section of the following illustration shows branches of the bush clover and a close-up of its flower. The upper right shows Miyata Masayuki’s representation of the prostitutes. The lower part of the illustration shows a Japanese silk-painting of bush clover and moon on a set of sliding doors from the 19th Century.

The haiku has been extensively discussed. Ueda (1991) quotes from Koseki:

The bush clover stands for the courtesans, the moon for Basho. The bright moon in the sky and the delicate, lovely bush clover are friendly with, yet keep a certain distance from, each other. Basho and the courtesans associated with each other in a similar way as they shared the same lodging.

Basho kept his distance both because of his asceticism, and also because he leaned toward the homosexual in his longings (Leupp, 1997).

However, the moon might also represent the heavens looking down on the transient life of human beings. Sin and redemption, beauty and mortality, are of little import sub specie aeternitatis

In 1943, scholars found Sora’s diary of the journey to Oku. This confirms most of the details of Basho’s book, which was put together a few years after the journey had been completed. However, it makes no mention of the episode with the prostitutes, and some have suggested that Basho’s account was therefore fiction rather than fact. Perhaps only the dream of a tired traveler.

Last Years

Basho’s journey to Oku came to an end in Ogaki. He spent several months there and in the environs of Kyoto before returning to Edo where he put together his memory and notes of the journey to form Oku no Hosomichi. He undertook several other shorter journeys over the next few years, finally falling ill and dying in Osaka in 1694 (Ueda, 1970; Kikaku, 2006).

One of his last haiku was:

Tabi ni yan-de

yume wa kare-no o

kake-meguru

Ill on a journey,

my dreams still wandering round

over withered fields.

(trans. Toshiharu Oseko, 1990)

Basho was buried according tohis request near Minamoto no Yoshinaka, a famous Samurai general from the 12th Century. In one of the Noh plays, Kanehira, the spirits of the general and his companion wander around after death seeking rest.

Translations of Oku no hosomichi

Carter, S. (2020). Bashō: Travel writings. Hackett.

Hamill, S. (2000). Narrow Road to the Interior and other writings. Shambhala

Keene, D. (illustrated by M. Miyata, M., 1996). Oku no hosomichi. Kodansha International.

Korman, C., & Kamaike Susumu. (illustrated by Hayakawa Ikutada, 1968). Back roads to far towns. Grossman Publishers.

Nobuyki Yuasa. (1966). The narrow road to the Deep North: and other travel sketches. Penguin.

Sato, Hiroaki. (1996). Bashō’s Narrow Road: spring and autumn passages: Narrow Road to the Interior and the renga sequence A Farewell Gift to Sora. Stone Bridge Press.

Collections of Basho’s Haiku

Reichhold, J. (illustrated by Shiro Tsujimura, 2013). Basho: the complete haiku. Kodansha USA.

Fitzsimons, A. (2022). Basho: the complete haiku of Matsuo Basho. University of California Press.

Toshiharu Oseko (1990 and 1996). Basho’s haiku: literal translations for those who wish to read the original Japanese text, with grammatical analysis and explanatory notes. Volume I and Volume II. Toshiharu Oseko

Ueda, M. (1991). Bashō and his interpreters: selected hokku with commentary. Stanford University Press.

Young, D. (2103) Moon woke me up nine times: selected haiku of Basho. Alfred A. Knopf

General References

Aitken, R. (1978). A Zen wave: Bashō’s haiku & Zen. Weatherhill.

Blyth, R. H. (1949). Haiku: Volume I Eastern culture. Hokuseido (reprinted 1981, Heian International).

Carter, S. D. (1991). Traditional Japanese poetry: an anthology. Stanford University Press.

Carter, S. (1997). On a bare branch: Bashō and the haikai profession. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 117 (1), 57–69.

Kikaku, T. (translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa, 2006). An account of our master Basho’s last days. Simply Haiku: A Quarterly Journal of Japanese Short Form Poetry, 4(3)

Leupp, Gary P. (1997). Male colors: the construction of homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press

Ueda, M. (1970). Matsuo Bashō. Twayne Publishers (reprinted 1982, Kodansha International).

In a times of stress and worry in my world,this work is refreshing and delightful to me !

Thank you

Old poems provide gentle accompaniment to the falling leaves.

Terry.

This is a beautiful piece and makes me wish that I could visit these magical places.

I am reminded of a lovely book by Robert Sibley, who used to write for the Ottawa Citizen when it was worth reading, A Rumour of God: Rekindling belief in the age of disenchantment. Sibley describes his pilgrimage on the trail that I presume you also walked. He ends with a haiku: “Wind shakes blossoms From Nyotai’s cherry tree Spring snow greets henro.”

My Haiku for today: Evening rain turned to snow End of Autumn Winter now.

Cheers Bob N

Glad you liked the post. I enjoyed your haiku. I shall look for the Sibley book. Terry