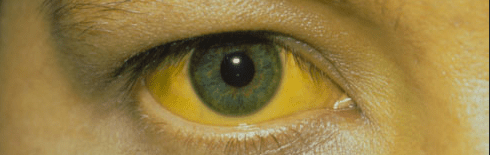

This was the second episode in a two-part series called “The Eyes Have It”. In the first episode we talked about the connection between Wilson disease and copper deposition – the Kayser-Fleischer ring. For this episode, we discussed something else that deposits in or around the eye: bilirubin.

Unlike with Kayser-Fleischer rings – a difficult to see finding in a rare disease – icterus is absolutely something that most students who have been on a surgical or medical ward for even a few weeks have seen.

It’s conjunctival, not scleral

One of the most fascinating parts of the answer is worth noting early: the sclera do not become jaundiced; instead it is the overlying conjunctiva. There are a few pieces of evidence in support of this. One is a letter published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in December 1979. The letter – written by two ophthalmologists – could not be any more to the point. It is titled “Conjunctival icterus, not scleral icterus.”

The two authors note that they had studied histological sections of globes from many patients with jaundice. They write, “We found that of all ocular tissues, the least amount of bilirubin staining is seen in the scleral stroma.” In one of their cases, the serum bilirubin reached 60 mg/dL and yet there was no bilirubin in the sclera.

The letter goes on to note that that bilirubin appears in the conjunctiva. More specifically, the bulbar conjunctiva that covers the sclera. It actually makes sense that we can identify jaundice by examination of the eye: as the overlying conjunctiva becomes jaundiced, the underling sclera appears yellow (but only appears so).

Why the conjunctiva?

There are a couple of explanations. One relates to a molecule to which bilirubin readily binds: elastin. Tissues with high concentrations of elastin are more apt to become jaundiced. One example is the conjunctiva. This was reported way back in 1930. The article is in German, though Google translate can help!

Another part of the explanation is that the conjunctiva has a rich vasculature. As the serum bilirubin increases, blood delivers more bilirubin to highly vascular structures such as the conjunctiva. The sclera, on the other hand, is relatively avascular.

One more recent case report helps to demonstrate that it is conjunctival not scleral icterus – and it did not require removal and transection of the globe. Instead, the authors show an image of a patient with chemosis (i.e., edema) of the conjunctiva. The area with chemosis showed “scleral icterus”. The area without chemosis lacked icterus.

But why elastin?

The answer to this question has no clear answer. Possible explanations could be approached from at least two perspectives: one structural and one teleological. The structural question asks, what is it about elastin that allows it to bind bilirubin? The teleological question asks, what purpose does this binding serve?

Structurally, elastin is considered an “albuminoid” protein, meaning it is albumin-like. Whether there is enough homogeny to explain the binding of bilirubin to both proteins with strong affinity is not clear.

As to teleological benefit, one hypothesis is that the human body uses elastin as a place to “store” excess bilirubin that would otherwise have toxic effects. As bilirubin levels increase this can exhaust the ability of albumin to store it. When this happens, the free bilirubin moves into tissues and could lead to toxicity. The most obvious example is the brain where unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia may cause kernicterus. Perhaps elastin provides another binding site for bilirubin, thereby protecting against its toxicity.

Why has “scleral icterus” as a term persisted?

There is a longer history of nomenclature related to jaundice of the eye. Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine – which had eight editions starting in 1892 – defined icterus as “tinting of the skin and conjunctivae.” And the first six editions of Cecil’s Textbook of Medicine – published between 1927 and 1943 – also note that the jaundice is localized to the conjunctiva. It wasn’t until the 1940s that the term “scleral icterus” became commonly used. Ironically, this was based on the same data mentioned earlier demonstrating that bilirubin binds to elastin (at that time, the sclera were felt to be endowed with higher concentrations of elastin). But even this was not correct – the conjunctiva are richer in elastin than the sclera.

Fast forward to the 1979 letter which, for some reason, had no effect on our language and the medical community continued to use the anatomically inaccurate term “scleral icterus”. Sadly, more than 40 years later, nothing has changed. A final interesting observation about this letter: it has been cited just 13 times. If nobody sees “practice changing” literature, practice cannot change.

Take Home Points

- It is conjunctival (not scleral) icterus!

- Bilirubin binds elastin

Learning objectives

- Critically examine the use of “scleral” icterus” when describing jaundice of the eye

- Understand that bilirubin binds elastin and therefore has a predilection for tissues with high elastin content, including conjunctiva

- Generate explanations for the persistence of “scleral icterus” despite evidence showing that the term is inaccurate.

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (1.00 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (1.00 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (1.00 hours).

Listen to the episode

Credits & Citation

◾️Episode and show notes written by Tony Breu

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Breu AC, Abrams HR, Cooper AZ. Why does bilirubin deposit in the eyes? The Curious Clinicians Podcast. January 20, 2021. https://curiousclinicians.com/2021/01/20/episode-17-why-does-bilirubin-deposit-in-the-eyes/

Image credit: https://www.indiamart.com/proddetail/jaundice-treatment-18916823073.html