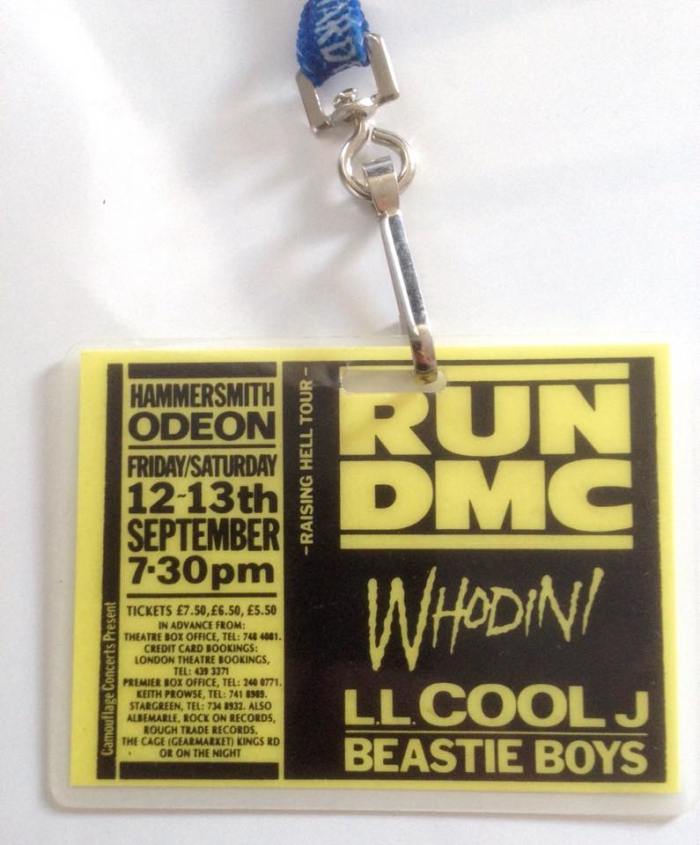

It’s 1986 and I am a fresh-faced skinny 23 year old. I’m working for Roadstar PA Systems of Sheffield who are located in the Socialist republic of South Yorkshire (sic) in the UK. Roadstar are the new upstart audio hire company supplying large concert PA systems to international rock ‘n roll bands like The Eurythmics, The Alarm, Runrig and a host of other bands that have long since disappeared into obscurity. I’d only worked for this company for 18 months when I’m told my next tour will be a Def Jam Record’s package ‘Raising Hell Tour’ of Europe featuring; Run DMC, Whodini, LL Cool J and The Beastie Boys. Back in 1986 very few people, me included, had heard of Def Jam Records and I remember being very disappointed that my boss at Roadstar had assigned me to this tour. I was bottom of the heap on the audio crew, my job was to set up and pack down the audio equipment and I didn’t even get to touch a mixing console, never mind mix a band. On paper this wasn’t a very appealing gig, in fact it sucked big time. The ‘bands’ weren’t actual bands but one bloke playing some records, with one or two, or in the case of The Beastie Boys’, three blokes shouting over the top of these beats. The first show was two nights at the Hammersmith Odeon in London on Friday 12th and Saturday 13th September 1986. Because I’d left school at the age of 16 my education was extremely limited and I didn’t know that the name Odeon was the name used to describe ancient Greek and Roman buildings built specifically for music; singing exercises, musical shows and poetry competitions. With 39 years of hindsight, and lots of expensive education behind me, the name seems very apt. In Europe, back in the mid 80s, Hip Hop music was a relatively new phenomenon, and as with anything new, it was largely misunderstood and mistreated by the media.

Rap music’s antecedents lie in various story-telling forms of popular music such as talking blues, spoken passages in gospel music, and the call and response of field music. Its more direct formative influences came from the 1960s, with reggae DJs toasting over strong bass beats, and stripped down styles of funk music, most notably James Brown’s use of ‘stream-of-consciousness’ raps over elemental funk beats. Initially this was part of New York’s dance scene where it had morphed out of block parties at which DJs played percussive breaks of popular songs using two turntables to extend the breaks. Black and Hispanic kids would competitively ‘rap’ over these breaks to gain kudos in their neighbourhoods. You can see the appeal of this music in Thatcher’s unfair, unjust urban locations. Zeitgeist; there’s that word again; it appears in almost every Album Rescue Series entry. Two sold out nights at London’s 3,500 capacity rock venue; the Hammersmith Odeon, was pretty impressive by four new unheard of New York ‘bands’ signed to an unknown obscure niche record label. Due to trouble outside the venue before and after these shows, Hammersmith Odeon refused to host any more rap groups for several years afterwards. This is a pattern of events would follow us around the world for the next few years.

At the production rehearsal, held early afternoon before the first show, we had a pretty big problem. Last band on the bill, The Beastie Boys, had taken an instant dislike to Roger ‘the Hippy’ who was supposed to be mixing their front of house sound. Roger came with the PA system and had a pretty impressive track record of mixing bands like Nils Lofgren and Katrina and The Waves. This palmares did not impress the Beastie Boys and it was obvious that Roger’s unfamiliarity of this new genre was problematic. Just before doors, the Beastie Boys hit the stage for their sound check. It was like a gigantic chaotic atom bomb going off. DJ Mix Master Mike was dropping some huge phat beats at a ridiculous high volume while the already sloppy drunk MCA, Ad Rock and Mike D start running around the stage screaming, “turn this shit up”. It was powerful, chaotic, and primeval, it was also kind of scary in an aggressive way and as a punk rocker I relished every single second of it. In complete opposition sound engineer Roger was not enjoying a single second of it and he tried to control this chaotic shambles by asking, “Could the lad in the red cap please give some level on the radio mic and the rest of you please shut up”?

I was stood at the side of the stage like a punk rock Aristotle watching this epic Greek tragedy unfold when Mike D (the lad in the red cap) grabs hold of me and screams “Yo homie, you know how to mix mutha-fucking sound right?” Indeed I mutha-fucking did and on the spot they tumultuously fire Roger and promote me to front of house engineer. Result! I’m only 23 and I’m now the front of house engineer for the most exciting band on the planet. A few months later, in 1987, I’m re-united with the Beastie Boys when we embark on their headline world tour to support the newly released debut album License To Ill. I guess these guys liked my attitude. I spent the next few years of my life touring the world as live sound engineer for The Beastie Boys and that made me very happy indeed. My personal mantra has always been “do what you love and love what you do”. It started that day and I’ve stuck to it.

So why this album rescue; everybody loves this album and has fond memories of it? With over 10 million albums sold, it’s an undeniable retail success. Granted it took 30 years for the album to achieve its Diamond status, but that’s a considerable number of albums to shift by anyone’s standards. Not only did the punters buy it by the truckload, but the music press loved it too as did lots of radio stations. Licenced to Ill was the first rap album to reach number one on the USA’s billboard charts and it’s the eighth best selling [1] rap album of all time. This pattern repeated all over the world although huge sales do not constitute a great album alone.

Surely all of these metrics prove that this album is not in need of an album rescue? OK, I’m pushing the boundaries here. This is not so much an album rescue, as a critical reappraisal, which is a rescue of sorts. With this album Mike D, Ad Rock, the late MCA and their record company, Def Jam, pulled off the greatest post-modern Rock ’n’ Roll Swindle of all time. Licensed To Ill remains the most creative and intelligent post modern parody ever created in any creative medium. There I’ve said it. When the Beasties Boys rap about drinking, robbing, rhyming, partying, fighting, pillaging and brass monkeys, we should really contextualise this subject matter through the lens of situational ethics. The father of situational ethics, Joseph Fletcher (1966) stated, “all laws and rules and principles and ideals and norms, are only contingent, only valid if they happen to serve love”. This album was definitely born out of love and I believe that it’s almost impossible to be critical of anything created out of love. In situation ethics, right and wrong depend upon the situation. There are no universal moral rules or rights, each case is unique and deserves a unique solution. As with other great parodies e.g. David Bowie’s (1967) The Laughing Gnome, a parody of Anthony Newley, the artist needs to fully understand and love the material that they are engaging with.

Maybe the correct way to rescue this album is to re-imagine, re-evaluate and re-contextualise it? Through this process we can construct an alternative discourse to the commonly misheld one. The buffoonery and cartoon controversy normally associated with this album can be dispelled and instead I’d like to reposition this album, as a deeply intelligent work of art, created by artists not fools. Granted the creators don’t do themselves any favours with their post-modern slapstick shtick parody. As with all post modern texts it’s all about surface, hedonism and fun devoid of any substantial meaning, which is why most people don’t fully appreciate this album. Licensed To Ill is a remarkable ironic marriage of heavy metal guitars, funk beats and edgy poetic rap lyrics. Hand crafted under the tutelage of producer and Def Jam founder Rick Rubin, this album is a substantial ground breaking piece of historical work.

Rap music was not supposed to be made by rich privileged upper class Jewish kids. Had they played by the rules then they would have become the stereotypical doctors, lawyers, dentists, accountants or even presidential candidates. But their privilege and education provided the cultural capital fuel that ignites this album. Having an acute understanding and passion for different subcultures, pop culture, jokes, music, fashion and art all provided the foundational material on which this album was built. The traditional elements of rap, such as guns, ghettos, money, hoes, sex and drugs are largely eschewed or at least re-appropriated via intoxicating creative wordplay. Their parody was so impenetrable and utterly convincing that it wasn’t immediately apparent that their obnoxious, misogynistic, hedonistic patter was a consciously constructed part of their persona. Luckily for us the passing years have clarified that this album was a huge postmodern joke made all the funnier by those taken in by the joke or completely unaware of the joke.

This album is a classic example of what French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss termed “bricolage”. This album is the sound of the Beastie Boys acting as classic bricoleurs. They are taking some very specific symbolic objects such as music, language, clothing, appearance and forming a unified signifying system in which these ‘borrowed’ materials take on a new and more powerful significance. Not only is the notion of bricolage at play in their music, but it’s also at play (literally) in items such as VW car badges, clothing and even their language e.g. the use of the word “homie” as a shortened version of “home boy”. Criticism about the Beastie Boy’s lack of conviction and authenticity abounded at the time. They were unfairly compared to the punk rockers that a decade before them had taken to the streets to hurl bricks at the riot police. They consciously understood that punk rock had achieved zero and that the youth of the mid 1980s was not prepared to face the tear gas and baton charges. Instead the Beastie Boys instigated a much more effective covert semiotic guerrilla war and it was all expertly delivered under the cloaking device of extreme parody. Their work on this album and every other album they have made is intellectual, inter-textual, is constantly in dialogue with other forms of cultural expression and it can only be fully appreciated when it is located in its original context, which is in the mid 1980s.

Listening to the cajoling rhymes of this album in 2015, filled with clear parodies and absurdities, it’s difficult to imagine the offense that many people took back in the 1980s. This is one of the funniest and most infectious albums ever made and it’s all articulated via the gonzo literation of some posh bratty Jewish kids from New York who in all probability are much cleverer then we are. The parody of this album is not offensive to the traditional black rappers; instead it points its undercover barb at frat college jocks and lager louts; the people who bought the album. Their hedonistic beer soaked version of life was intoxicatingly aspirational, in an alternative way, and made to look very appealing via their gleeful delivery. The subject matter of this album is completely contradictory to the dominant mid 1980’s monetarist aspirations because it celebrates the very conditions of its enforced leisure; namely boredom, meaninglessness, dehumanisation, commodity fetishism, repetition, fragmentation and superficiality. Track seven, the huge worldwide mega hit of Fight For Your Right (To Party), is the personification of their new worldview.

The mid 1980s were a time of money, MTV, excess and spring break in warm sunny nirvanas such as Panama City and Daytona Beach. The interesting thing about Fight For Your Right To Party is that it was originally intended to be a parody of popular party rock songs of the time like Twisted Sister’s I Wanna Rock, although that intent was seemingly lost on the audience. It’s as if The Beastie Boys where insider dealers (something that was also popular in the mid 1980’s) and were poking fun at their own kind. Just sampling and scratching Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin to hip-hop beats does not make for an automatically good record, though there is definitely a visceral thrill to hearing those muscular riffs put into super serious overdrive. Their artistry wasn’t just confined to the writing and recording of the album but also in their exceptional understanding of the media as a conduit or delivery system for their powerful message.

This debut album, and its subsequent tour, provoked moral panic and media outrage resulting in tabloid headlines across the world. The Beastie Boys instantaneously became the latest folk devils, the band that the media loved to hate. Popular myth would be fuelled by stories of the band’s controversial behaviour. The media and popular tabloid press amplified and greatly exaggerated events on this tour out of all proportion, which greatly increased album sales. In part this was due to the exuberant stage show that was purposefully designed to mimic the album. As a member of that tour, I saw none of this behaviour, what I saw was lots and lots of identical looking hotel rooms, airport lounges, venues and the inside of tour buses. I remember helping a very home sick MCA backstage in Germany make a collect call to his mum and dad back in New York. Album Rescue Series is no place for these antidotes but you will be able to read them in my forthcoming book Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before. The Beastie Boys and their producer Rick Rubin had read Stephen Davis’ version of Led Zeppelin’s hotel destroying tour exploits, Hammer of the Gods (1985), and it had made a big impression on them all. Not only is the album’s lyrical content heavily influence by this book and lifestyle, but the album cover’s artwork is also highly inter-textual.

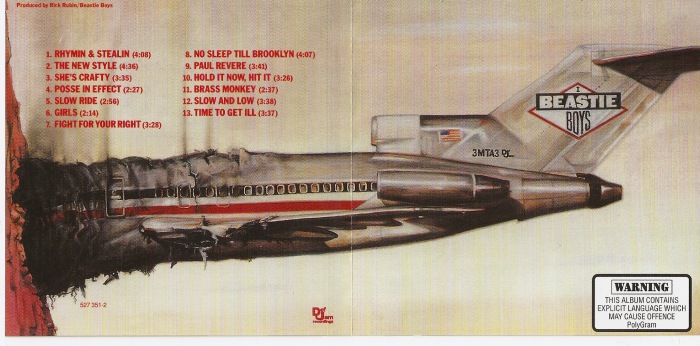

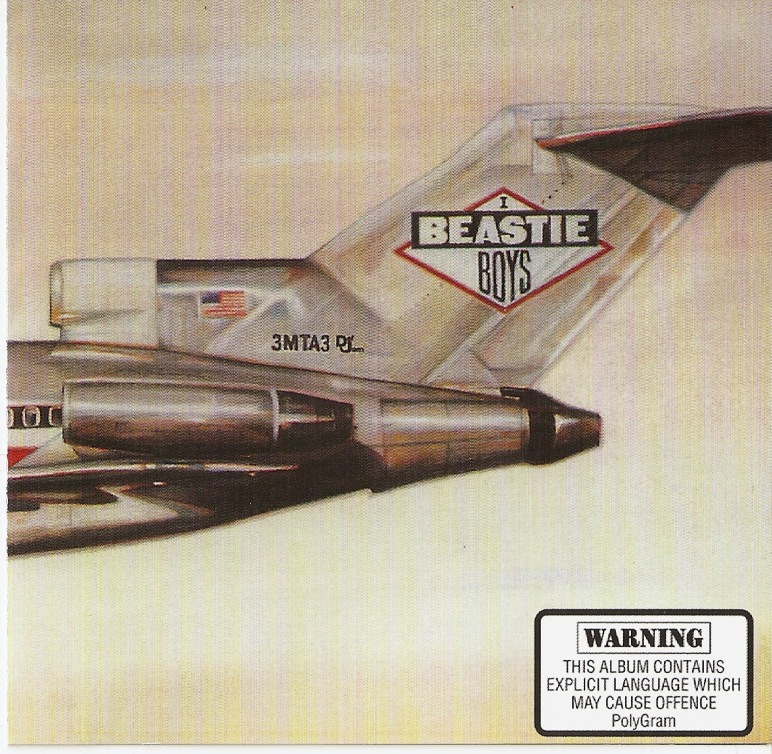

The smouldering aeroplane crashed into the side of a mountain cover illustration is a deceptively complex piece of work both artistically and semiotically. The image is darkly humorous, but not out of step with the times or the sonic content of the album. Artist David Gambale (aka World B. Omes) created a pre-Photoshop collage of various airplane parts then illustrated over it using water-soluble crayons. I’m not an artist but I’m guessing the process must have taken significant hours and the dramatic results are worth it. The plane on the album cover is an inter-textual reference to the legendary Starship, a Boeing 720 airliner owned by Bobby Shering and converted into a kitsch rock-star flying tour bus. Led Zeppelin were the Starship’s most famous occupants and even wrote the song Stairway To Heaven about their on board experience. The Starship would transport any rock band that could afford the exorbitant hire fee e.g. The Rolling Stones, Bad Company, Allman Brothers. Stripped of it’s reference, an aeroplane is not glamorous, its merely an ecologically unsound, inefficient and very expensive form of transport. Ever since “the day the music died” (McLean D. 1972) back in 1959, when a chartered flight claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Richie Valens, and the Big Bopper, plane crashes have ended the careers of some of music’s biggest names. Patsy Cline’s plane went down in 1963, silencing one of the greatest voices to ever crossover from country music to popular music. We lost the great Otis Redding to an airplane accident in 1967, and just a few years later, singer-songwriter Jim Croce’s career was terminated just as it was starting to take off. Perhaps none of the above was as startling as Lynyrd Skynyrd‘s horrific 1977 plane crash, which killed three members of the band, the assistant road manager, co-pilot and pilot. Airplanes are symbols of both extravagant rock star excess and sombre tragedy. What better way to announce a new young band to the world than to crash their jet into the side of a mountain before their career had even taken off? Just like a centre page fold out cartoon from the Mad comic, the fun is in the details. The plane’s tail number “3MTA3” spells “Eat Me” backwards. The Beastie Boys logo on the vertical stabilizer was intentionally designed to evoke the Harley-Davidson logo. Many people have commented about the connotations of how the smouldering plane resembles a stubbed out spliff. Via this album, the Beastie Boys are displaying an advanced understanding of semiotics that Roland or Ferdinand would be immensely proud of here.

I am quite prepared to stick my neck out here and argue that the Beastie Boys have never made a bad record: Paul’s Boutique (1989), Check Your Head (1992), Ill Communication (1994), Hello Nasty (1998), To The 5 Boroughs (2004), The Mix-up (2007) and Hot Sauce Committee Part 2 (2011) are all masterpieces in their own right. Even their other parody record, The In Sound From Way Back (1998), which precisely parodies Perrey and Kingsley’s 1966 album of the same name, is another masterpiece. If we ignore the 10 million copies sold of License To Ill and listen to it minus the filter of parody then we are getting very close to rescuing this album. It isn’t only the music or the rhymes that translate beyond the parody crime scene. License To Ill clearly shows the Beastie Boys didn’t give a fuck at exactly the time when the world desperately needed to be shown how not to give a fuck. Flying in the face of rampant yuppie materialistic capitalism they demonstrated that you could be ground-breaking, cutting edge, important, creative and relevant all at the same time yet still have no goals beyond getting drunk and partying hard.

Licensed To Ill marks the turning point in cultural history when the slacker generation (the three members of band are born 1964, 65 & 66) start making music for the millennial generation. This album proved that you could live life as one giant inside joke, speaking in tongues and making hilarious obscure references to Chef Boyardee or Olde English 800 and no one outside your circle of jerks would be any the wiser. Oh how we laughed. License To Ill accurately predicted the future to the Millennials upon its release in 1986. The mantra bestowed on them was “follow your dreams” and because they were constantly being told they were special, this cohort tends to be over confident. While largely a positive trait, the Millennial’s confidence has been known to spill over into the realms of entitlement and narcissism. They are the first generation since the Second World War that is expected to be less economically successful than their parents. The Millennial’s optimism is founded in unrealistic expectations, which often leads to disillusionment. Most Millennials went through post-secondary education only to find themselves employed in low paid dead end jobs in unrelated fields to the ones they studied or underemployed and job-hopping more frequently than any previous generation. License To Ill soothsaid this bleak scenario but then also gave us a not too cryptic optimistic answer, which was “Fight for your right to party”. I rest my case.

[1] http://www.musictimes.com accessed 11th August 2015

The Album Rescue Series (ARS) book will be launched on November 16th 2015 during Melbourne Music Week. The ARS book will feature 35 albums that the press and general public considered to be far from exemplary of a particular artist. This book rights those wrongs. The ARS book is a contributive piece of work by music academics and scholars, each of whom take a unique approach to rescuing an album. This week’s Album Rescue is by Tim Dalton. (Follow Tim on Twitter: @touringtim)

Tim – would we be able to pick your brain about the Beastie Boys tour you worked on?

astrobboy [at] beastiemania [dot] com

LikeLike

Yes, you can pick my brain. Email me: touringtim@aol.com

LikeLike