What Is an Epigraph in a Book? (Plus Tips for Authors)

Many of the classics have them. They can be found in many big-name authors’ books today. Some of my clients include them.

As an avid reader, I often encounter this overlooked element in a book.

But as a book coach and editor who has worked on dozens of nonfiction books, I seldom encounter them in my clients’ first drafts.

Friends, I’m talking about epigraphs.

Few authors outside of those who publish with the big 5 publishing companies, it seems, are aware of the power of the epigraph.

And few authors—or readers, for that matter—know a whole lot about epigraphs.

What follows is a thorough guide to epigraphs, geared toward authors.

We’ll look at frequently asked questions about epigraphs and I’ll share tips and examples galore with you. You can see more examples from nonfiction books here.

Below, you will find the following FAQs:

What is an epigraph in a book? And where does an epigraph go?

Where do epigraphs come from?

What is the purpose of an epigraph?

Does a book need an epigraph?

How to write an epigraph?

Where does an epigraph go in a book?

How to format an epigraph in a book (Chicago Manual of Style)?

Epigraph vs. epitaph, and epigraph vs. epigram: what’s the difference?

Epigraphs, in sum

What is an epigraph in a book? And where does an epigraph go in a book?

An epigraph (pronounced EP-ih-graff) is a brief quotation that precedes the text of a book.

Epigraphs, as we will see, are far more than just quotes.

Placed at the beginning of a book, book chapter, or book section, epigraphs ease readers into the narrative. Epigraphs are meant to grab the reader’s attention, to make the reader pause and think.

In his blog post for The Write Practice, John MacIlroy suggests that a well-chosen epigraph draws the reader in and makes them want to “open the door” to what’s next.

As Bennet Bergman notes, “Some books have more than one epigraph, placing two or more quotations in dialogue with one another.”

The epigraph at the beginning of The Handmaid’s Tale has three epigraphs!

The Purpose Driven Life has nearly 100 epigraphs; they precede each part and each of that book’s 40 chapters. (More on where to put epigraphs later.)

Where do epigraphs come from?

Epigraphs have been around for centuries—at least as early as The Canterbury Tales.

Often called “mottos,” epigraphs became popular in Europe in the early 18th century (1700s).

By the 19th century, they were ubiquitous, featuring in the works of Melville, Austen, and others. In the 20th century, Faulkner, Hemingway, Morrison, King, and others used epigraphs, and their popularity continues to the present. (For more on the history of the epigraph, see Rachel Sagner Buurma’s essay in The New Republic.)

As Rachel Sagner Buurma explains, “epigraphs allowed an author to rightly place (and justify) their work as a piece of the ever-growing literary conversation.” They helped signal where a given work “fit” vis-à-vis other previous works or that it was in the same vein.

Over time, authors became increasingly creative with their use of epigraphs.

According to Epigraphia, “More and more, authors are using epigraphs to make points about the literary past, political statements, and even jokes that resonate throughout their works.”

The material for the epigraphs themselves is often drawn from the following sources:

literature or poetry

Quotes from literature or poetry, including classics, are and have historically been, the most popular source of epigraphs.

Writers are well read, so it should be little surprise that they quote other books and poems in their epigraphs.

Among the 50+ epigraphs in Richard Adams’s Watership Down are quotes from Aeschylus, Browning, Renault, Malory, Tennyson, Yeats, Thomas, Hardy, Austen, Carroll, Dostoevsky, de la Mare, and Shakespeare.

Faulkner novels often provide material for epigraphs.

Can’t go wrong to quote one of the classics!

historical figures like philosophers, scholars, and world leaders

The writings of world leaders are often used in epigraphs. These might be philosophers, world leaders, even celebrities.

In Watership Down, author Richard Adams quotes Clausewitz, Napoleon, and Wellington. Many others quote Greek and Roman orators.

The shortest epigraph that I’ve encountered, in Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) by Thomas Pynchon is simply the quote “What?” attributed to Richard Nixon.

Kwame Alexander’s novel He Said, She Said (2013) has an epigraph with this Barack Obama quote: “The future belongs to young people with an education and the imagination to create.”

It would not be surprising to see epigraphs from Plato, Cicero, or Socrates, from Edison, Einstein, or Steve Jobs, from Winston Churchill or Mahatma Gandhi, or Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

religious texts, proverbs, or maxims

Examples of epigraphs in a book. These epigraphs, which quote the Bible, appear before chapter 16 of The Purpose Driven Life by Rick Warren.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Bible is often the source of epigraphs—and not just in religious books.

Rick Warren’s Purpose Driven Life is loaded with epigraphs; often there are two epigraphs before each chapter or part.

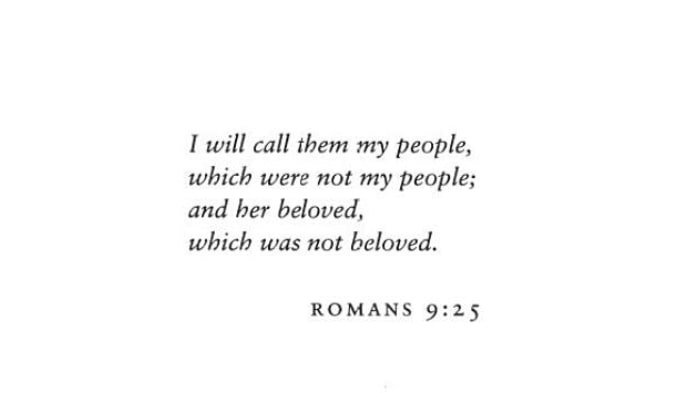

Several of Toni Morrison’s novels have epigraphs from the Bible, epigraphs that could be interpreted a number of ways and make the reader ponder what they might mean. Beloved begins with one such epigraph, from Romans 9:25.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood often uses Biblical quotes in its many epigraph.

In the epigraph that precedes Chessie: The Cultural History of the Chesapeake Bay Sea Monster, author Eric A. Cheezum quotes Job 41:1–9 (NIV), about the Leviathan.

In The Periodic Table (1975), author Primo Levi has this epigraph:

Troubles overcome are good to tell.

—Yiddish Proverb

films and songs

Movie quotes and song lyrics occasionally inspire epigraphs.

Stephen King’s epigraphs are often song lyrics.

One of the epigraphs in What Color is Your Parachute? A Practical Manual for Job-Hunters and Career-Changers by Richard Nelson Bolles is a quote from Cinderella: “Fairy Godmother, where were you when I needed you?”

In Beautiful People by Simon Doonan is the epigraph attributed to Dorothy Gale in The Wizard of Oz: “Some of it wasn’t very nice, but most of it was beautiful.” In this funny memoir, the author is alluding to his family. The decision to quote Judy Garland’s character is no coincidence; she is a gay icon and the author is gay. The reference fits Doonan’s book and would be appreciated by the likely readers.

I would advise you NOT to use song lyrics—unless they’re in the public domain or you have permission from the rights-holder.

Brief quotes from other works of fiction—and even from movies—have been commonly allowed as “fair use.”

But songs are another matter. The music industry has traditionally been very active in defending copyright.

➡️For more on using lyrics in an epigraph in your book, see this article from Lloyd Literary.

There is no clear-cut guidance on what is fair use and what is not, on what will get you sued and what won’t.

And most book publishers will require you to get permission, which is a frustrating, time-consuming, expensive, and potentially fruitless process.

It’s rarely worth it.

Here’s what CMOS, 4.87 has to say:

“Epigraphs. Quotation in the form of an epigraph does not fit neatly into any of the usual fair-use categories but is probably fair use by virtue of scholarly and artistic tradition. The same can be said of limited quotation of song lyrics, poetry, and the like in the context of an interior monologue or fictional narrative.”

But The Copyeditor’s Handbook, p. 449, has this advice:

Using “[a]ny quotation from a poem, novel, short story, play, or song that is still under copyright . . . may require permission.”

As The Copyeditor’s Handbook, p. 449, note 22, observes, “Extensive paraphrasing and even short quotations and even short quotations for purposes other than the presentation of evidence or examples for analysis, commentary, review, or evaluation may not be considered fair use. For this reason, . . . some publishers may require an editor to obtain permission for epigraphs and other undiscussed quotations if the original work is still under copyright.” Just to play it safe, I suppose, because the laws are vague and no one wants to be sued.

Simply stated, you may need formal permission to use song lyrics in an epigraph. Publishers may require it. And without permission, you may open yourself up to being sued.

the author’s own words

Some authors write their own epigraphs.

As Rachel Sagner Buurma notes in her essay in The New Republic, “George Eliot invented almost half of Middlemarch’s chapter epigraphs; [Sir Walter] Scott and Stendhal were known for similar fabrications.”

Kurt Vonnegut’s epigraphs quote his own characters as though they are real people.

Here are some examples:

We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories.

In The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) by Margaret Atwood, before one of the chapters.

One of the best examples of the fictional epigraph is this one in The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald:

Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too.

Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!

—Thomas Parke D’Ivilliers

Faulkner quotes a poem that doesn’t exist and attributes it to a fictional character in another one of his books!

That poem or “quote” is attributed to a character from another novel he wrote. Faulkner quotes that character as if the character had written the poem he’s using as an epigraph.

This quote alludes to the dogged determination that Jay Gatsby displays in pursuing a married socialite. It is used to foreshadow.

other, often surprising sources

As Rosemary Ahern points out in the “Unexpected Sources” chapter in her book The Art of the Epigraph, epigraphs can come from a variety of unusual sources, such as advertisements, museum guides, political speeches, comic books, and children’s books.

Here’s one unique example in The End Games by Michael Martin (2017):

Everything not saved will be lost.

–Nintendo “Quit Screen” message

This epigraph is used in a thriller novel about two gamer half-brothers facing a zombie apocalypse, this epigraph introduces the theme of the book.

Rick Riordan’s Trials of Apollo series has epigraphs that are haikus!

In the modern era, one might also expect to see memes or quotes from viral videos providing material for epigraphs.

The epigraph at the beginning of the novel Little Bee by Chris Cleave, an example of an epigraph format in an ebook.

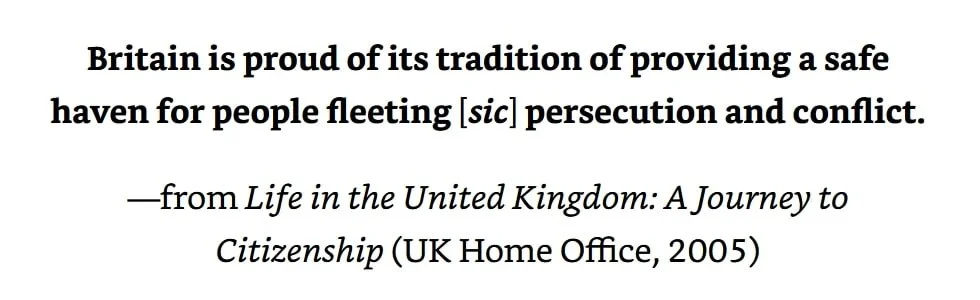

Government publications are another possible source of epigraphs—and they’re public domain, so yay!

In Little Bee by Chris Cleave, a novel about the struggles faced by a young Nigerian refugee in England, is the epigraph shown here.

What is the purpose of an epigraph? Why do authors use epigraphs?

What the author is trying to do with an epigraph may be open to debate. Some epigraphs may serve more than one purpose or have more than one meaning.

In any case, here are several reasons why authors use epigraphs, or several purposes epigraphs serve.

to convey a theme, thesis, or message

This is the most common reason, and I could come up with numerous examples. Let’s focus on one.

The past is never dead. It's not even past.

—William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

This quote is an epigraph in The Fifth Generation: A Nez Perce Tale (2009) by Linwood Laughy; The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010) by Michelle Alexander; Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI (2017) by David Grann; Spare (2023) by Prince Harry.

In Laughy’s book, the epigraphs serves as a reminder of how Indigenous people see time. Each chapter focuses on one of protagonist Isaac Moses’s ancestors and reveals the historical events which have shaped Isaac’s life.

In The New Jim Crow, the epigraph alludes to Alexander’s premise, that “mass incarceration is, metaphorically, the New Jim Crow.”

In Killers of the Flower Moon, which is about the murders of Osage Indians in Oklahoma in the 1920s and the subsequent FBI investigation, the epigraph suggests that Indigenous people continue to face the legacy of the violence and injustice inflicted upon them.

In Spare by Prince Harry, this could refer to a number of things, in my view: a claim that the British monarchy should be a thing of the past but isn’t; the notion that what happened to Princess Diana isn’t in the past; the notion that what’s transpired between him and members of the Royal Family isn’t over with.

to introduce humor, irony, or contrast

Sometimes an epigraph makes you laugh. Sometimes it’s sarcastic or ironic.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

—Jane Austen

This “truth” is not (yet) what Bridget Jones is finding in Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) by Helen Fielding. And if that were true in Austen’s time, it doesn’t seem to be true in Bridget’s time. And because this is not true, there’s a whole novel centering on Bridget’s love life.

Other times it sets up a contrast—between characters, ideologies, or perspectives.

to set the tone

If they give you ruled paper, write the other way.

—Juan Ramón Jiménez

In Fahrenheit 451 (1953) by Ray Bradbury; The Lovely Bones by Susie Salmon; and If They Give You Lined Paper, Write Sideways (2007) by Daniel Quinn.

First used in a dystopian Bradbury novel, this epigraph makes the assertion that people must question and challenge authority. It sets the tone, as you expect some sort of act of rebellion.

“Don't Panic.” That is the epigraph in Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. It’s almost as if to say, “buckle up, you’re in for a wild ride.”

It’s also the epigraph in the fantasy novel The Ocean at the End of the Lane by Neil Gaiman. This epigraph sets the tone for The Ocean at the End of the Lane as an “out there” story that also has some heavy themes.

In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson is the epigraph “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man,” from 18th-century British writer Samuel Johnson. We can tell there is going to be some self-destructive behavior involved.

to provide context

Kristin Kieffer explains this better than anyone.

A great example of an epigraph that provides context is the poem that is placed at the beginning of each book in The Lord of the Rings trilogy by J. R. R. Tolkien. It gives clues to the question “Who is the Lord of the Rings?” The poem was written by Tolkien for the express purpose of utilizing it as an epigraph.

As Kieffer writes, “Other epigraphs that fall into this category may serve to reveal the time period during which the novel [or nonfiction book] is set, share vital backstory details, clue readers in on important character relationships, or explain a world-building concept. In any case, the important thing to remember when creating an epigraph that fulfills this purpose is that it must be presented in a way that intrigues and hooks the reader.”

When providing context, an epigraph may also offer insight into the era of the book or the setting in which it takes place.

to introduce a character

A great example of this is the passage from Dante’s Inferno that’s the epigraph for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus:

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me Man, did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?

—Paradise Lost, X, 743-45

Does a book need an epigraph?

No. A book doesn’t need an epigraph. The decision to include an epigraph is purely optional; many books don’t contain epigraphs.

How to write an epigraph

Here are some tips for authors when it comes to writing an epigraph for a book:

Tip 1. Find a quote that “fits” your book.

Remember, epigraphs typically do one or more of the following things:

Make sure it serves a clear purpose or fits your book perfectly. To quote Well-Storied’s Kristen Kieffer, “Every element in your [book] should serve a purpose. Epigraphs are certainly no exception to the rule.”

On a related note, some epigraphs “match” the genre of the book. A history book might have a quote from a historical figure. A humorous memoir might use a quip from a comedian. A fantasy novel might use a quote from mythology. Many Christian nonfiction books have epigraphs from the Bible.

Tip 2. Be brief.

Being brief is key; keeping your epigraph brief, you’re less likely to bore or confuse the reader. Feel free to use ellipses (. . .) to trim unnecessary words from the quote. Most epigraphs are a few words, a line, a few sentences. Some are longer (the original poem in The Lord of the Rings comes to mind), but such examples are rare.

Tip 3. The use of epigraphs should be “logical” and “balanced.”

STET: A Handbook for Authors from the University of North Carolina Press, p. 20, advises the following:

“For best effect, epigraphs, when employed in a manuscript, should be presented in a logical, balanced manner—one (or more) for each numbered chapter, for example, or none for numbered chapters but one for a prologue and one for an epilogue—rather than being used for some chapters but not for others.”

Tip 4. Format your epigraph appropriately.

The epigraph needs to stand out from the rest of the text, and this can be accomplished with indentation or alignment choices, font or font size choices, as will be discussed later.

Tip 5. Make sure your direct quote matches the original.

If you’re quoting a work of literature or a religious text especially, replicate it precisely. That means duplicate the spelling, punctuation, and capitalization of the original.

Get the quote right, and try to confirm that it was actually said or written by the person you’re attributing it to. And/or say “Attributed to ___.”

The opening epigraph to The Godfather has this epigraph:

Behind every great fortune there is a crime.

—Balzac

Balzac never actually said that. It’s a simplification of a statement by French writer Honoré de Balzac, according to Quote Investigator, “and no single person can be credited with the construction of the modern concise and forceful version.”

Again, it’s OK to use ellipses to cut unnecessary words, so long as the overall meaning remains the same.

And when attributing a quote, spell the person’s name correctly!

Tip 6. You don’t have to be original.

You can be original. It would be nice if you were, but as you can see in some of the examples I provide in this article, there are quotes that have been used as epigraphs in many books. And there are instances where you may be using the same quote as another author, but to make a different point.

Tip 7. Wait until you’re done writing your book to choose the perfect epigraph(s).

Collect ideas as you go, but wait until your book or chapter is fully formed to find an epigraph that fits.

Where does an epigraph go in a book?

As mentioned earlier, epigraphs may be placed

1) at the beginning of a book

2) at the beginnings of each chapter (occasionally)

3) at the beginnings of sections within chapters (rarely)

Let’s look at each option now.

For epigraphs at the beginning of a book:

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), 1.37, states that the epigraph goes in the front matter of a book with these guidelines in mind:

“If there is no dedication, the epigraph may be placed on page v.”

If there is a dedication, it is placed on page vi, opposite (before, and to the left of) the table of contents.

“If there is no dedication, the epigraph may be placed on page v.”

According to CMOS, 1.7, dedication and epigraph pages do not contain page numbers; page numbers do not appear “on blank pages or on ‘display’ pages” such as the half title, title, copyright, dedication, and epigraph, and further, a page number may or may not be used on the opening page of the table of contents, foreword, and preface.

For epigraphs preceding chapters:

The epigraph appears below the chapter title. It is considered part of the “chapter display.”

One option is to not have any epigraphs preceding the chapters but instead to use chapter titles that hint at the theme of the chapter or otherwise accomplish the purposes that an epigraph would have.

For epigraphs preceding sections within chapters:

The epigraph goes below the subhead for the new section or below the ornament or typographical break—be it a set of asterisks or stylized line—that marks the beginning of the new section

How to format an epigraph in a book

From CMOS, 13.36:

“Quotation marks are not used around epigraphs. . . .”

“Like block quotations, epigraphs receive a distinctive typographic treatment—often being set in a smaller typeface and indented from the right or left, and sometimes italicized.”

“Treatment of sources, which are usually set on a separate line, also varies, though more than one epigraph used in the same work should receive consistent treatment.”

From The Chicago Manual of Style, 1.37:

“The source of an epigraph is usually given on a line following the quotation, sometimes preceded by a dash (see 13.36). Only the author’s name (in the case of a well-known author, only the last name) and, usually, the title of the work need appear; beyond this, it is customary not to annotate book epigraphs” but an epigraph “may include a note reference, though traditionalists may prefer an unnumbered note” (CMOS, 1.49; see also 14.52).

So, should an epigraph be cited with a footnote or endnote?

Not necessary. Not common.

From The University of North Carolina Press’s STET, its formatting guidelines for authors, p. 20: “As devices to set the scene or tone in a chapter, epigraphs do not ordinarily require documentation. It is sufficient to give the source under the epigraph, citing only the author; if desirable or helpful, the work and/or date may be added [I read that to mean “may,” not “must”], but no further bibliographic information is provided with the epigraph itself or in a note.”

STET adds this friendly reminder on p. 7:

“When indenting extracts, epigraphs, etc., use whatever commands your word processor has for changing the left margin. Do not hit the hard return or insert extra spaces to achieve the effect of an indentation.”

Also, . . .

Style every epigraph the same way. Whether it is an epigraph in the front matter or at the beginning of a chapter makes no difference.

The table of contents does not include the epigraph.

Epigraphs are not indexed (CMOS, 16.109).

Here are a few additional examples of epigraph formatting options:

What do readers think of epigraphs?

Some readers dislike epigraphs, finding them pretentious. Others find them distracting. Epigraphs, they feel, takes them out of the flow of the book.

Some readers zip right past them.

But the well-chosen epigraph can add much to a book.

Those who do read it will have something to ponder.

They’ll get insight into where the author might be going next. They’ll get a hint as to the relationship between the epigraph and the text that follows. And that could be very exciting and very valuable to them.

epigraph vs. epitaph, and epigraph vs. epigram

What’s the difference between an epigraph and an epitaph?

An epigraph (a quote placed at the beginning of a text) is not an epitaph (a phrase or form of words written in memory of a person who has died), especially as an inscription on a tombstone.

What’s the difference between an epigraph and an epigram?

An epigraph may be an epigram. As Bennet Bergman notes, the two are often confused; “they’re both short, highly quotable blocks of text.” But an epigram is a statement that is “short, witty, often satiric,” whereas “An epigraph is primarily defined by its location (it is always found at the beginning of a text) and by the fact that it is a quote of a different text.”

If an epigraph happens to be punchy, witty, maybe even satirical, then it may also be an epigram.

Such may be the case, Bergman says, in To Kill a Mockingbird. In that novel is the epigraph “Lawyers, I suppose, were children once,” a quote from English writer Charles Lamb. It is brief, clever, and satirical.

Epigraphs, in sum

A well-chosen quotation put at the beginning of a book, chapter, or section, the epigraph is meant to grab the reader—to draw them in—to give clues into what follows, pique their curiosity, and inspire them to turn the page.

Drawn from various sources—literature or poetry, historical figures, films and songs, the author’s own words, or other, often surprising sources,

epigraphs can have many purposes. They are often meant to introduce or sum up the theme, topic, or thesis of the book or chapter; establish the tone or mood; inject humor, irony, or contrast; provide clues into a character or paint a picture of the time period or setting. They might foreshadow. They are often intended to elicit an emotional response on the part of the reader.

Epigraphs are a fun way for authors to express themselves and to show their creativity. In a related sense, as Rosemary Ahern writes in The Art of the Epigraph, p. xiii, “Epigraphs remind us that writers are readers.”

Epigraphs are an often-overlooked component of books—fiction and nonfiction alike.

I hope you’ve found the FAQs, tips, and examples of epigraphs to be helpful—

And I hope if you’re writing a book, you discover the power of the epigraph.

Resources on epigraphs/sources quoted

Books

The Art of the Epigraph: How Great Books Begin by Rosemary Ahern

The Copyeditor’s Handbook, 3rd edition

The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition

Articles

a database of epigraphs by Graham John Mathews and Francis Bond

“Do Epigraphs Matter?” by Rachel Sagner Buurma

“Epigraph” by LitCharts

“How to Empower Your Writing with an Epigraph” by John MacIlroy

“Should You Include an Epigraph in Your Novel?” by Kristen Kieffer