ROBERT E. SUMPTER OF THE UNITED STATES CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

ROBERT E. SUMPTER OF THE UNITED STATES CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

What Oral Health Professionals Need to Know About Syphilis

Detecting syphilis early is integral to its successful treatment.

This course was published in the September 2018 issue and expires September 30, 2021. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence of syphilis.

- Identify the etiology and pathogenesis of syphilis.

- Explain the clinical signs and symptoms of syphilis.

As an infectious disease that is relatively easily treated with antibiotics,1 syphilis declined sharply after the discovery of penicillin. However, the number of syphilis cases has been rising in the United States and worldwide, especially in developing countries.2,3 A particular danger of syphilis is transmission during pregnancy and development of congenital disease, resulting in fetal death or varying levels of disability, and the rate of congenital syphilis has also been increasing.2,4 Due to the frequent occurrence of syphilitic ulcers in the oral cavity, perioral regions, and head and neck areas, oral health professionals must be knowledgeable about the disease signs and symptoms, diagnosis, transmission, prevention, and treatment protocols.

Syphilis remains a globally prevalent disease with approximately 18 million cases and 5.6 million new cases occurring annually.3,5 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyze trends in syphilis based on the reports of primary (initial stage, which manifests as small sores in the genital and oral regions) and secondary disease stages (if left untreated, syphilis moves to the secondary stage which typically presents as a rash) , when the disease is symptomatic and contagious.2 As a communicable infectious disease, syphilis requires notification of laboratory confirmed cases to the local/state departments of health, which then report the cases to the CDC.6,7 The lowest recorded rate of primary and secondary syphilis was in 2000-2001, at 2.1 cases per 100,000 population, after which the number has steadily increased.2 In 2016, the syphilis rate was higher in men than in women (15.6 vs 1.9 cases per 100,000) and a majority of reported cases were in men having sex with men (52.3%).2 Although much lower than in men, rates in women doubled from 2012 to 2016, and continue to rise. There was a 35.7% increase in 2015-2016, with the highest incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in women ages 20 to 24 (6.7 cases per 100,000). Not surprisingly, this increase among women was accompanied by the rise of congenital syphilis (628 cases in 2016, an 86.9% increase compared with 2012).2

Co-infection of syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is high, especially among men having sex with men (47% in 2016),2 and the relationship between the two infections is complex, including potential acceleration of progression of either infection, altered clinical and laboratory presentation of syphilis, and decreased response to antibiotic therapy. Primary syphilis in patients with HIV may be symptomless, while overall the infection is more aggressive.8 Additionally, presence of syphilitic ulcers serving as portals for viral entry increases the chance of HIV infection.9

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, a Gram-negative, microaerophilic, highly motile spirochete, characterized by its corkscrew appearance, and invisible by light microscopy due to its size of only 6 μm to 20 μm.1 Dark-field microscopy is the definitive method for syphilis diagnosis.4,10

Syphilis is transmitted by direct contact with primary or secondary lesions or by vertical transmission at any time during pregnancy.1,9 T. pallidum is invasive and able to penetrate skin and mucosa through micro-abrasions, as well as endothelial, placental, and blood-brain barriers early in the infection process and reach regional lymph nodes within minutes, followed by wide dissemination within hours post-inoculation.1,5 T. pallidum cannot be cultivated in an artificial medium, making the study of its pathogenesis and treatment/prevention approaches, specifically vaccine development, challenging.5,9

Genome sequencing of T. pallidum completed in 1998 revealed some unique features of the bacterium that allow it to evade immune response and persist in the host tissues for decades. With limited biosynthetic capacity, T. pallidum relies on the host for its metabolic needs and it has few surface membrane proteins that can be targeted by antibodies. On the other hand, it produces porins, hemolysins, and adhesins that permit the microorganism’s attachment to host cells, invasion of tissues, and its dissemination.1,5,9

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Following inoculation, syphilis follows a well-described progression1,4,8 from primary to secondary stage of varied duration that can often overlap. Untreated, the disease will progress to the latent stage, which is symptomless, and can relapse to secondary manifestations and become infectious. About 15% to 40% of cases will progress to the tertiary stage years to decades later.1,9 Serious organ damage and death can occur in the tertiary stage.

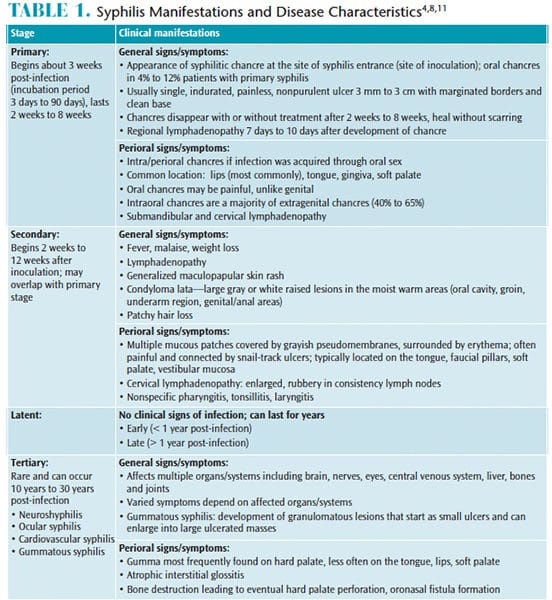

Syphilis is manifested by general and perioral signs and symptoms summarized in Table 1.4,8,11 The disease is known as “the great imitator,” as it mimics signs and symptoms of various diseases and conditions, making clinical diagnosis difficult.1,8 Primary chancres (Figure 1) and secondary oral lesions (Figure 2) in primary and secondary syphilis are common and have nonspecific presentations.8,12–14 However, the disease may also follow an asymptomatic course: as many as 60% of patients with confirmed syphilis do not remember having any lesions,1 which may increase disease progress to the late stages and facilitate sexual and fetal transmission. The chance of developing the infection following exposure is estimated at 50%.8

CONGENITAL SYPHILIS

Congenital syphilis is the leading cause of stillbirth worldwide.5,15 Untreated maternal infections can result in fetal death (spontaneous abortion, stillbirth) in as many as 40% of cases.15 In the US, this proportion is much lower (5.5%) but represents missed opportunities for prevention of congenital syphilis.16 Time and stage of maternal infection during pregnancy influences the rate of fetal transmission and clinical outcomes. Infections earlier in pregnancy have a higher possibility of fetal and perinatal death and congenital infection than later in pregnancy, and disease in earlier stages has higher fetal transmission rates (70% to 100% in primary stage vs 10% in late latent stage).1,9 While dangerous, congenital syphilis is also preventable by prenatal screening and antibiotic treatment.15,16 The CDC recommends testing for syphilis at the initial prenatal visit for all pregnant women. Patients at high risk of infection can have testing repeated twice in the third trimester.17 A single dose of 2.4 million units benzathine penicillin G intramuscularly is effective in preventing negative pregnancy outcomes and is the only recommended treatment; in case of allergy to penicillin a desensitization therapy is recommended.1,17 While other treatment options, such as erythromycin, azithromycin, tetracycline, doxycycline, and ceftriaxone are available, they are not recommended during pregnancy because of their inability to cross the placenta (erythromycin, azithromycin), adverse effects for the developing fetus (tetracycline, doxycycline), or insufficient data on safety and effectiveness (ceftriaxone).17

patient with confirmed syphilis.IMAGE CREDIT: SUSAN LINDSLEY OF THE UNITED STATES CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

Fetal transmission occurs after the 16th week in utero, and various organs and systems, including facial/oral structures and teeth, developing during the time of fetal infection become affected and demonstrate early (in the first 2 years of life) and late (occurring after age 2) clinical manifestations.1,18 Early features include diffuse maculopapular rash with desquamation frequently involving palms and soles, osteochondritis involving most frequently upper limbs and knees, periostitis that sometimes involves the clavicles and bones of the skull, and persistent rhinitis with highly contagious discharge.1,8,18 Early skin inflammation around the mouth can lead to permanent radial scarring known as rhagades and other early orofacial manifestations include atrophic glossitis, yellow discoloration of the lips, and high-arched narrow palate.18 Late manifestations of congenital syphilis include Hutchinson’s triad of interstitial keratitis of the cornea, sudden sensorineural hearing loss occurring at ages 8 to 10, and dental anomalies.1,18

Dental manifestations include characteristic appearance of permanent molars and incisors, or Hutchinson’s incisors, which are barrel-shaped, short and narrow, with a vertical notch at the incisal edge.18 The two appearances of the molars associated with congenital syphilis are small, dome-shaped, smooth crowns (Moon’s molars or bud molars) and with a deep groove around the base of the crown caused by enamel hypoplasia (mulberry molars or Fournier’s molars).18 These typical dental malformations are found in about 65% of children with syphilis, although other nonspecific findings, including rapid attrition/abrasion and hypoplasia and pitting near the incisal and occlusal surfaces of the affected teeth, are often present.18

Diagnosis of congenital syphilis in infants, especially neonates (< 30 days old), is difficult because the presence of maternal antibodies transferred through the placenta can complicate serologic findings. The CDC recommends several penicillin-based treatment algorithms19 based on the presence of disease in the mother; adequacy of her treatment prior to delivery; and clinical, serological, and radiographic findings in the infant determining the presence/likelihood of congenital disease. Frequent laboratory testing and careful follow-up by pediatric infectious disease specialists are necessary to ensure treatment success.19,20

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of current disease is based on the clinical findings, thorough evaluation of exposure history, and laboratory confirmation by direct or indirect T. pallidum detection methods.4,7 Visualization of bacteria in a sample obtained from a chancre or a secondary lesion by dark-field microscopy remains the definitive diagnostic method, although it is rarely performed.4 Other direct methods include polymerase chain reaction and direct fluorescent antibody assays; however, the diagnosis is most frequently confirmed by indirect serological methods determining the presence of antibodies to T. pallidum.4,7 The traditional diagnostic algorithm consists of nontreponemal tests detecting the antibodies to cardiolipin—a substance elevated in many chronic conditions, including syphilis. Positive result is followed by treponemal tests specific to anti-T. pallidum antibodies.4,7 A reverse algorithm employs treponemal tests first, followed by nontreponemal.7

A rapid point-of-care test used by clinicians in-office was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014. Performed in 10 minutes using the patient’s whole blood (fingerstick), this test offers the convenience and speed for screening and initial testing that must be confirmed by a laboratory analysis in case of a positive result. However, its accuracy—reported at more than 97% in studies leading to the FDA approval—was recently found to be much lower, with only 71.4% sensitivity and 91.5% specificity.21 Further studies are needed to determine the test’s usefulness in various health care settings, especially where phlebotomy is not available.

TREATMENT

Penicillin preparations (benzathine, aqueous procaine, aqueous crystalline) administered parenterally for various duration depending on the stage of the disease are the recommended treatment for syphilis.17,19,20 Selection of the agent depends on the location of bacteria and organs/systems involved, because some forms of penicillin are better at reaching the sequestered sites such as the central nervous system (neurosyphilis) or aqueous humor of the eye (ocular syphilis), or able to pass through the placental barrier to reach the fetus.17,20 Combining different penicillin preparations is not recommended and in cases of allergy to penicillin without reported life-threatening reactions, penicillin desensitization is advised.22 Although other antibiotics can be used, they are not recommended for the treatment of neurosyphilis, congenital syphilis, or during pregnancy.17,19,20

CONSIDERATIONS FOR ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Frequent occurrence of syphilitic ulcers in every stage in the oral cavity and perioral regions necessitates clinicians’ alertness. Using all diagnostic criteria for lesion assessment is crucial for differential diagnosis. Nonspecific appearance of primary oral chancres (Figure 1, page 32) and secondary mucosal lesions (Figure 2, page 35) can lead to misdiagnosis as fungal infections, aphthous stomatitis, attributed to previously diagnosed HIV infection, or simply blamed on stress.12,13 Inappropriate treatment with antifungal, antiretroviral, and steroid anti-inflammatory medications will not benefit the patient, and, in the case of corticosteroid therapy, can trigger exacerbation of infection.12 Expected spontaneous resolution of primary and secondary syphilitic lesions may be misconstrued as successful treatment of the disease, while, in fact, it will progress into latency with a possibility of recurrence and advancement into the tertiary stage. Discovery of indurated lesions with regional lymphadenopathy should prompt a thorough investigation of patients’ medical, social, and sexual histories, although patients may not be open to such discussion.13 Lesions suspected as related to syphilis should not be biopsied because histopathology of syphilis is not diagnostic and shows nonspecific inflammatory changes.8,12 Dental/dental hygiene treatment not related to management of oral lesions should be postponed until they resolve; otherwise there are no required modifications to dental procedures or commonly prescribed medications in dental practice.11 Strict adherence to standard precautions is necessary to prevent transmission to health care providers, which was reported before the universal use of gloves.8

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals may encounter perioral manifestations of syphilis with increased frequency and may be the first clinicians to evaluate the manifestations of disease in patients seeking treatment for their oral lesions. Prompt referral to a medical practitioner or an infectious disease specialist who can offer diagnostic testing for syphilis will ensure correct diagnosis and timely treatment.

REFERENCES

- Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187–209.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance—Syphilis. Available at: cdc.gov/std/stats16/Syphilis.htm. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Disease Watch Focus: Syphilis. Available at: who.int/tdr/publications/ disease_watch/syphilis/en. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis—CDC Factsheet. Available at: cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis-detailed.htm. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Lithgow KV, Cameron CE. Vaccine development for syphilis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16:37–44.

- Matthews A. Reporting requirements for infectious diseases. Decisions in Dentistry. 2016;2(10):12–16.

- Association of Public Health Laboratories. Suggested Reporting Language for Syphilis Serology Testing. Available at: aphl.org/AboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID_Suggested_Syphilis_Reporting_Lang_122015.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Ficarra G, Carlos R. Syphilis: the Renaissance of an old disease with oral implications. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:195–206.

- Peeling RW, Hook EW. The pathogenesis of syphilis: the great mimicker, revisited. J Pathol. 2005;208:224–232.

- Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C, Benea V, Georgescu S. Brief history of syphilis. J Med Life. 2014;7:4–10.

- Little JW. Syphilis: an update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:3–9.

- Dybeck Udd S, Lund B. Oral syphilis: a reemerging infection prompting clinicians’ alertness. Case Rep Dent. 2016;2016:6295920.

- Hertel M, Matter D, Schmidt-Westhausen AM, Bornstein MM. Oral syphilis: a series of 5 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:338–345.

- Scott CM, Flint SR. Oral syphilis—re-emergence of an old disease with oral manifestations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:58–63.

- Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Saleem S, Reddy UM. Infection-related stillbirths. Lancet. 2010;375:1482–1490.

- Bowen V, Su J, Torrone E, Kidd S, Weinstock H. Increase in incidence of congenital syphilis—United States, 2012–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1241–1245.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis During Pregnancy. Available at: cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis-pregnancy.htm. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Nissanka-Jayasuriya EH, Odell EW, Phillips C. Dental stigmata of congenital syphilis: a historic review with present day relevance. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:327–331.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines—Congenital Syphilis. Available at: cdc.gov/std/tg2015/congenital.htm Accessed August 23, 2018.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines—Syphilis. Available at: cdc.gov/std/tg2015/syphilis.htm Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Matthias J. Notes from the field: evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of a commercially available rapid syphilis test—Escambia County, Florida, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1174–1175.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines—Management of Persons Who Have a History of Penicillin Allergy. Available at: cdc.gov/std/tg2015/pen-allergy.htm Accessed August 23, 2018.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2018;16(9):32,35–37.