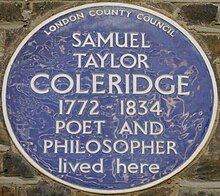

Today (21 October) marks the anniversary of the birth of poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was born in Devon, England in 1772. A leader of the British Romantic movement, his best known poems are: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Christabel, and Kubla Khan. His idealism is best exemplified perhaps by his ultimately unsuccessful attempt to establish a utopian community with friend and fellow poet Robert Southey.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

By 1793, Southey aged nineteen and a student at Oxford University, had grown disillusioned with the lack of reform that characterised the aftermath of the French Revolution, and by the persistence of inequality in his native England. As a result, his thoughts turned to a simpler life in America, a new world untainted by the evils of established society.

Robert Southey

In 1794, Southey was introduced to Coleridge, a student at Cambridge University. They founded a firm friendship on their common commitment to social justice and civil liberty, and formulated a plan to move to America, where they would establish Pantisocracy. This new word was derived from ‘Pan-socratia’, the Greek word for governance by all. They considered ‘Aspheterism’, the holding of property in common ownership, as a key principle. Southey envisaged Pantisocracy as a society:

…where the common ground was cultivated by common toil, and its produce laid in common granaries, where none are rich because none should be poor, where every motive for vice should be annihilated and every motive for virtue strengthened.

Underpinning their scheme was a melange of ideas garnered from the writings of Plato, Paine, Priestley, Hartley, Godwin, and Dyer. This new utopia would, they believed, arise from a commitment to benevolence and civil liberty, a concern for human rights, and an awareness of the perfectibility of mankind. As Southey saw it:

Their wants would be simple and natural; their toil need not be such as the slaves of luxury endure; where possessions were held in common, each would work for all; in their cottages the best books would have a place; literature and science, bathed anew in the invigorating stream of life and nature, could not but rise reanimated and purified.

Women had a place in this idyll too, albeit a subordinate one. As Southey explained:

Each young man should take to himself a mild and lovely woman for his wife; it would be her part to prepare their innocent food, and tend their hardy and beautiful race.

Southey had a clear vision for how he and his fellow-idealist would spend their days, writing:

When Coleridge and I are sawing down a tree, we shall discuss metaphysics; criticize poetry when hunting a buffalo; and write sonnets whilst following the plough. Our society will be of the most polished order.

Originally, they thought of settling in Kentucky, but they shifted their sights to the Susquehanna Valley in Pennsylvania. The plan was to invite ten like-minded men and their families to join them. Initially, wealthier members would support the less well off until they became self-sufficient. They were certain that this would be the first of many such communes.

Susquehanna Valley, Pennsylvania

Although the pair planned to travel to the new world in 1795, they were woefully underprepared. As a result of having studied the misleading promotional accounts that were reaching England from America, they underestimated the physical labour required to set up a new community. For some reason, they assumed that only four hours a day need be dedicated to work, the rest being available for contemplation.

Funding was also an issue. The original plan was that Southey’s wealthy aunt, Elizabeth Tyler, would put up capital. However, when she learned of his plans, and worse still his intention to marry seamstress Edith Fricker, she disinherited him and ejected him from her house into a violent rainstorm. As a result, Southey scaled back the plan. He began to talk of settling on a farm in Wales, of hiring servants to do the bulk of the manual labour, and of retaining private ownership of land with the exception of a small plot to be held communally.

Coleridge was incensed and condemned Southey as a traitor. Since he too had believed he would need a wife to accompany him to America, he had married Edith’s sister Sarah, but theirs was an unhappy union. He never returned to Cambridge but began his career as a writer instead. Having spent some time collaborating with William Wordsworth, he dedicated the next two decades to composing poetry, lecturing on literature and philosophy, and publishing tracts on religious and political theory. Although he lived off grants and donations for the most part, he did spend two years on the Island of Malta working as Acting Public Secretary of Malta under the Civil Commissioner, Alexander Ball, a post he had accepted in an effort to overcome poor health and a calamitous addiction to opium.

Unable to break his dependence on opium,Coleridge moved to London in 1816, to live in the home of his physician, James Gillman. Although his behaviour was erratic, and he developed a conviction that the world was about to end, he continued to produce wonderful work, including Biographia Literaria, a volume of his finest literary criticism; Sibylline Leaves; Aids to Reflection; and Church and State.

Coleridge died in London on July 25, 1834. The cause of death was recorded as heart failure compounded by a lung disorder that may have resulted from his opium addiction. He was sixty-one and had lived separately from his family for two decades by then.

You can find the modern day Pantisocracy, an excellent cabaret of conversation presided over by Dr Panti Bliss at this link here.

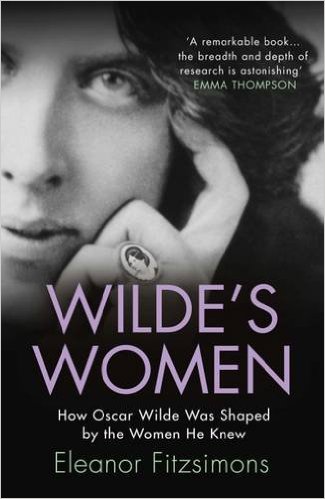

Coleridge has absolutely nothing to do with Oscar Wilde or Wilde’s Women, but you might like to read it anyway.