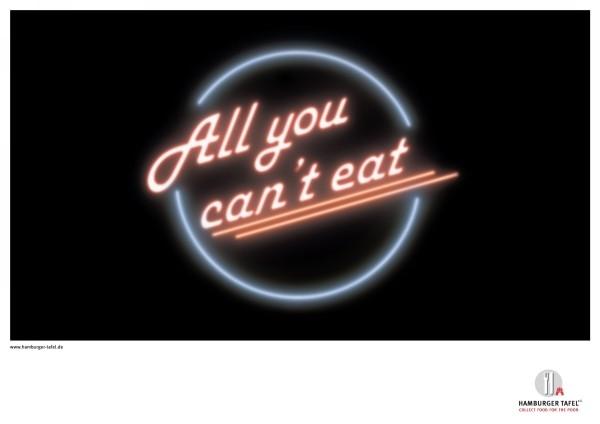

When was the last time you had a truly awful meal? I don’t just mean forgettable, I mean sensationally, spectacularly crook.

When was the last time you had a truly awful meal? I don’t just mean forgettable, I mean sensationally, spectacularly crook.

Some time ago it occurred to me that since I began my career as a food writer I have become so jaded, so critical, so judgemental about the food served to me that a horrendous meal is far more thrilling than just another masterpiece.

So I want to talk about bad meals. They can be divided into three categories: Domestic Disasters, Professional Calamities and Foreign Fiascos. Let’s cook off with an entry in the Domestic Disasters category.

The woman who was to become my wife and I had just set up house together. It was to be our first dinner party. I had elected to cook a strange dish from the 1970 edition of Elizabeth David’s Italian Food, Cephalonian Hare, Lepre di Cephalonia.

I’d first cooked this dish in Spain. There, I made it in what is known in my part of Spain as a greixonera – a wide-mouthed terracotta dish that sits on the open fire. It was extraordinarily good, in spite of the seemingly incongruous ingredients. I could find no hare, but rabbits abounded, indeed my next door neighbour bred them, and they were very large. Almost hare-like. Now before the recipe and the disaster, here is a little snippet of information about rabbits, and Spain.

Around 3200 years ago, the Phoenicians arrived in what is now known as Spain and decided to stay awhile. One of the novelties they found there was a small, furry, tailless animal with long ears and legs which bred rapidly. It looked like an animal they knew as a hyrax, so they called the new land I-shepan-ha, land of hyraxes. When the Romans arrived they Latinized the name to Hispania, which then became España.

Anyway, this particular rabbit, which was originally an Italian rabbit (to add to the countries named after animals list, the first people to arrive on the Italian peninsula were called Italici, from an ancient word meaning ‘land of young cattle’ or ‘land of calves) is marinated in lemon juice, then fried with onions, a dozen cloves of garlic and red wine, among other things.

Back in Australia I cooked mine in an aluminium quart pot. Those among you who understand the chemistry of food are already gagging: lemon juice and aluminium. It turned a sort of aluminium oxide grey. When asked to taste it (I wouldn’t), my wife’s comment was “it tastes like excrement” – more or less.

We bought in French from around the corner. Our guests were none the wiser. To this day, she need only say the word “rabbit” to stop me crowing about my cooking.

Professional Calamities. Where do I start? The raw potato in the yellow Thai curry? No. The deep-fried battered tomato at the Chinese restaurant in Singleton? No. How about the boardroom lunch served in a NSW country town, at the headquarters of a prominent food-processing corporation? The corporation can now be named – Letona – as it is no longer. And no wonder.

After the factory tour, always an exciting event, my companion – a Master of Wine and a pretty good toother – and I were ushered into the boardroom. There sat two home economists in white coats. And there lay the meal they had prepared for us. It was an embarrassing moment, and one that I hope we handled with aplomb

In a large, rectangular, white crockery serving dish were diagonal strips of crumbled fetta, brined tuna, and tinned peaches. In a lattice-work pattern across the top of this were arranged tinned anchovies. It remained untouched.

And finally, a Foreign Fiasco. In Tunis, the very beautiful capital of Tunisia, I had met a charming man who had, it appeared, out of the goodness of his heart – for he asked nothing, and paid his way – taken three days off to show me around.

The culmination of this tour was a visit to his village to meet his mother, father and wife, and a lunch (his shout) at the local restaurant, where we were to try the local speciality. We had been communicating in my very bad school-boy French, and I thought I had been doing fine. ‘Maintenant,’ he said with relish, ‘nous mangeons tête d’agneau.’ My heart sank as the French words were translated by my tired brain. Sheep’s head. I had of course heard of the Arabic penchant for eating the head of sheep — but surely this was a dish of the desert Arabs, seated cross legged on sumptuous carpets in their massive tents — surely not my new friend Youssef, in his natty sports coat and grey flannel trousers? Apparently so. I had read somewhere that the eyes are the delicacy and are offered to the guest of honour.

We arrived at the restaurant, a simple whitewashed room in a dusty square, the only customers (I found later opened especially at lunch for Youssef, another reason for shame and remorse). I was nervous. Even my rudimentary French deserted me as my mouth dried up. Could I eat a sheep’s head? How would it be cooked? How would he hand me the eyes? As soon as I saw this head, I knew that I would not be able to do it.

The chef arrived beaming from the kitchen holding two large plates which, with a flourish, he placed on the table in front of each of us. And there it lay. On my plate. Neatly split in half fore and aft. Inside up. I could see half a tongue, dark grey on the outside, light grey on the inside, and half the muzzle, complete with teeth. In the skull pan, beneath a sprinkling of coriander leaves — as far as I could make out the only seasoning — half a brain, slightly mashed.

If I was to offer you a recipe for this dish, it would go thus: ‘First, find a dressed sheep’s head. Boil it in a pot large enough to submerge it in water until done — test by piercing the cheeks with a skewer, they should be tender, but should not separate from the skull. Remove from the water, drain, slice in half from forehead to muzzle, place on a plate and sprinkle with coriander leaves. Take immediately to the table.’

Youssef grabbed at the tongue, ripped it out and sliced off a chunk, devouring it hungrily. I timidly did the same. It tasted revolting, the texture was worse. It was cold and clammy. The rough grey outer coating was rubbery. But it looked exactly like what is was — a tongue, used by the sheep to lick and swallow.

I couldn’t do it. I apologised to Youssef as best I could in stumbling French. He was hurt, it showed in his eyes, but he hid it well, shrugged and ordered me a chicken stew. But I had completely lost my appetite. He ripped off the jaw and got stuck into it, dipping into the brains with a spoon. I could barely look. Afterwards, he took my untouched head home. My distaste was his dog’s good fortune.

The curious thing about this gastronomic failure of mine is that I quite happily eat brains, tongue and other organ meats on their own. It was, I am now convinced, the fact that they were still assembled — as parts of the head — that was my downfall.

For those who would like to try it, here is Elizabeth David’s Lepre di Cephalonia, as published in Italian Food:

‘A dish from the ionian Islands, but of Italian origin.

Cut up a hare and put it in a deep earthenware pot.Pour over it the juice of half a dozen lemons, add a little salt and pepper. Leave it to marinate for at least 12 hours.

When the time comes to cook it cover the bottom of a capacious or heavy pan with about 1/4 inch of fruit olive oil. When it is hot, put in a slice onion. Let it brown slightly, then add the pieces of hare. Brown them on both sides. Add about a dozen cloves of garlic, salt, pepper, a generous amount of origano, and a wineglass-ful of red wine.v (If the hare is being cooked in an earthenware pot heat the wine before pouring it in, or the pan may crack.) Cover the pan and simmer for two and a half or three hours.

This may sound outlandish but try it. The lemon flavour, the garlic, and the olive oil have an excellent effect upon the cloying and dry qualities of the hare. It is not, of course, a refined dish, and the wine chosen to go with it should be chosen accordingly.’

Classic David. ‘It is not, of course, a refined dish…’ Don’t tell De. I’m going to try it again.