Background

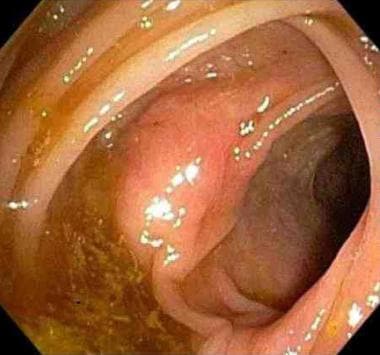

The term intestinal polyp is used to describe any projection arising from a flat mucosa into the intestinal lumen. Polyps can be pedunculated (see first image below) or sessile (see second image below).

See Benign or Malignant: Can You Identify These Colonic Lesions?, a Critical Images slideshow, to help identify the features of benign lesions as well as those with malignant potential.

Colonic polyps are usually classified as nonneoplastic, hamartomatous, neoplastic (adenomas and carcinomas), serrated (which can be neoplastic or nonneoplastic), or submucosal (which can be neoplastic or nonneoplastic). Adenomas account for approximately 65% of all colonic polyps, and serrated lesions account for the remaining 35%. [1] Approximately two thirds of all colorectal carcinomas are believed to arise from adenomas, a finding that underscores the importance of treatment and surveillance of adenomas of the gastrointestinal tract. The focus of this article is adenomatous colonic polyps, as shown in the images below.

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cause of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death. [2] Screening for premalignant adenomatous polyps has the potential of preventing CRC. Colorectal adenomatous polyps are therefore targets for intervention and they may also represent biomarkers for CRC risk.

Colonoscopic screening for adenomatous polyps and their removal results in a decreased risk of colon cancer. The National Polyp Study [3] demonstrated that removal of all colonic adenomas resulted in a 76% to 90% reduction in colon cancer incidence and a 53% reduction in mortality from colon cancer over long-term follow-up compared with historic controls.

A more recent concern is that colonoscopy does not necessarily protect against colon cancers proximal to the splenic flexure (right-sided colon cancers). [4, 5, 6] This is likely due to a combination of reasons, including technical issues, such as poorer bowel preparation in the right side of the colon and higher rates of missed or incompletely resected polyps in the right side of the colon (that tend to be more flat and more difficult to identify and remove). In addition, it is possible that right-sided polyps have different biologic characteristics that may make them more elusive to detection and more aggressive in their progression.

Despite these potential limitations, physicians should advise patients regarding available options for colorectal polyp and cancer screening. Consensus guidelines on the early detection and surveillance of colorectal cancer and polyps from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [7] were most recently published in 2008 and guidelines from the US Multi-Society Task Force (MSTF) on Colorectal Cancer [8] were updated in 2012.

Pathophysiology

The colonic mucosa is a self-renewing epithelium that is structured is a very tightly regulated balance between cell proliferation at the base of a crypt, maturation as colonocytes, migrate up the crypt, and extrusion of senescent and/or apoptotic cells from the upper crypt into the lumen. This entire process takes approximately 3-6 days.

Adenomatous cells are characterized by a loss of normal growth control. They continue to proliferate as they reach the top of the crypt, and they are not extruded into the lumen. Instead, they multiply and eventually fold back into the surrounding normal mucosa, inducing a response in the mesenchymal tissue that helps shape the microscopic architecture of the adenoma. The rate of growth and progression of adenomas to cancer is variable, but typically occurs in 10-15 years. [9] Patients with heritable forms of the disease, such Lynch syndrome, otherwise known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), have a significantly more rapid rate of adenoma formation and progression to cancer. [10]

The conventional adenoma-carcinoma sequence is thought to be a genetically driven process characterized by the occurrence over time of successive cycles of somatic mutation and clonal expansion of cells that have acquired a survival advantage. The first mutation in this process often involves inactivating mutations of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor gene (inherited mutations in the APC gene cause familial adenomatous polyposis [FAP], and somatic mutations in the APC gene occur in about 80% of sporadic adenomas).

Additional progressive mutations occur in cells of the adenoma, including activating mutations of the oncogenes (Ki-ras), and inactivating mutations of additional tumor suppressor genes (ie, TP53). Some of these individual mutations lead to clones of cells that have acquired a survival advantage over surrounding cells, leading to a clone of mutant cells. Subsequent cycles of mutation and clonal expansion ultimately lead to adenoma growth, increased severity of dysplasia, and ultimately, acquisition of the invasive and metastatic characteristics of an adenocarcinoma.

Lynch syndrome colorectal cancers (CRCs) also arise from or within conventional adenomas, but the process is driven by a germline mutation in one of the DNA mismatch repair genes (ie, MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2); when focal somatic or the remaining wild-type allele occurs in the colon, it leads to loss of DNA mismatch repair, an increased mutation rate, microsatellite instability, and a rapid progression to CRC.

An epigenetic pathway to CRC has been described that is thought to arise through a serrated polyp pathway (hyperplastic polyp, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas) rather than via conventional adenomas. In this pathway, silencing of DNA mismatch repair genes (MLH1) or other DNA repair genes (MGMT) by methylation results in failure of DNA repair and a resultant increased mutation rate that can result in progression to CRC. [9]

Another study suggests that activation of HuR, an RNA-binding protein implicated in immune homeostasis and various cancers, including CRC, is an early event in FAP-adenoma but not inflammatory bowel disease dysplasia and that HuR inhibition may potentially be an effective FAP chemoprevention. [11]

Etiology

Genetic predisposition

Up to 5% of all colorectal cancers are thought to arise from well-characterized inherited mutations. [12] Adenomatous polyps occur at a younger age and at a higher frequency in patients who carry these genetic predispositions.

Lynch syndrome

Lynch syndrome, otherwise known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is an autosomal dominant syndrome caused by the inheritance of a germline mutation in one of several DNA mismatch repair genes (eg, MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2). Only a few colon adenomas develop in patients with Lynch syndrome, but those that do appear to have a very high rate of progression to colorectal cancer (CRC). Patients with Lynch syndrome develop tumors at a younger age (mean age, 44 y), have tumors more commonly in the proximal colon (60% to 70% proximal to splenic flexure), and are more likely to present with a multiplicity of cancers. Lynch syndrome accounts for up to 3% of all CRCs. [13]

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant syndrome caused by the inheritance of a germline mutation in the APC gene. FAP is classically characterized by the appearance of hundreds to thousands of adenomas of the colon that typically begin during adolescence (average age at polyp formation is approximately 15 y) and a nearly 100% lifetime risk of colon cancer (average age at cancer development is approximately 40 y) if the colon is not removed. There is also an attenuated phenotype of FAP with which patients usually have fewer than 100 adenomas with a right-sided predominance. Attenuated FAP patients generally present later in life and have a 70% lifetime risk of developing CRC. FAP accounts for less than 1% of the total colorectal cancer risk in the United States. [14]

MUTYH-associated polyposis

MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) is an autosomal recessive syndrome caused by a biallelic inheritance of a mutation in the MUTYH gene, which is a part of the base-excision repair pathway involved in the repair of oxidative DNA damage. MAP has a variable phenotype, ranging from CRC without polyposis to up to 100 polyps. MAP results in a predisposition for both adenomatous and serrated polyps—both with malignant potential. [15]

Intestinal hamartomas

Multiple hamartomas of the intestine occur in the rare autosomal dominant syndromes of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, familial juvenile polyposis, and Cowden syndrome. Adenomatous change can occur within the hamartomas and lead to adenocarcinoma, most commonly of the colon and small intestine.

Family history

Although up to 5% of all CRCs can be traced back to well-characterized genetic mutations, up to 30% of all CRCs have a familial component. Any patient with a first-degree relative who has a colorectal cancer or a large or histologically advanced adenoma when younger than 60-70 years is at a moderately increased (ie, 1.5- to 2-fold) risk for developing an adenoma. [16]

Diet and lifestyle

Initial epidemiologic studies suggested that increased dietary fiber was protective for CRC and increased dietary fat was a risk factor for CRC. [17] Subsequently, the prospective Nurses Health Study and other large cohort studies showed that dietary fiber did not significantly affect the risk for colon cancer. Although some fruits and vegetables may be protective, dietary fiber alone seems to have little impact on colon cancer risk. [18] Several cohort studies have also cast doubt on the notion that dietary fat increases the risk for colon cancer, [18, 19] although red meat may increase the risk.

The dietary Polyp Prevention Trial demonstrated that a dietary intervention promoting a low-fat, high-fiber diet had no impact on the recurrence of adenomatous polyps compared with controls, including the total number of adenomas, the number of adenomas by site, or the number of high-risk or advanced adenomas. [20] A 17-year follow-up study revealed no impact of this 4-year dietary intervention on the total adenoma rate or colon cancer risk. [21]

Abdominal obesity is associated with an increased risk of adenomas. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or higher have a significantly higher prevalence of colorectal adenomas (odds ratio = 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-1.33; P< .01) when compared with those with a BMI of less than 25. [22] Physical activity has been consistently shown to be a protective factor for CRC and adenomas. [23]

The American Cancer Society makes the following lifestyle and nutrition recommendations for general cancer prevention [24] :

-

Achieve and maintain a healthy weight throughout life.

-

Be as lean as possible throughout life without being underweight.

-

Avoid excess weight gain at all ages. For those who are currently overweight or obese, losing even a small amount of weight has health benefits and is a good place to start.

-

Engage in regular physical activity and limit consumption of high-calorie foods and beverages as key strategies for maintaining a healthy weight.

-

Adopt a physically active lifestyle.

-

Adults should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity each week, or an equivalent combination, preferably spread throughout the week.

-

Children and adolescents should engage in at least 1 hour of moderate or vigorous intensity activity each day, with vigorous intensity activity occurring at least 3 days each week.

-

Limit sedentary behavior such as sitting, lying down, watching television, or other forms of screen-based entertainment.

-

Doing some physical activity above usual activities, no matter what one’s level of activity, can have many health benefits.

-

Consume a healthy diet, with an emphasis on plant foods.

-

Choose foods and beverages in amounts that help achieve and maintain a healthy weight.

-

Limit consumption of processed meat and red meat.

-

Eat at least 2.5 cups of vegetables and fruits each day.

-

Choose whole grains instead of refined grain products.

-

If you drink alcoholic beverages, limit consumption.

-

Drink no more than 1 drink per day for women or 2 per day for men.

Long-term smoking has a detrimental effect on the risk of developing colonic adenomatous polyps, and it confers an increased risk of CRC. Those who have long-standing history of smoking may have up to a 3-fold increase in risk of adenomas [25] and an approximately 2-fold risk of CRC. [26, 27]

There may be a potential association between radiotherapy and intestinal adenomatous polyposis leading to the development of gastrointestinal carcinoma. [28]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Colonoscopic [29] and autopsy [30] series suggest an overall prevalence of adenomatous polyps of 40% to 50% by age 50-60 years and some endoscopic series suggest even higher rates. The prevalence of colonic adenomas increases with age and varies depending on the inherent risk of colorectal cancer in a given population.

International statistics

Significant geographic variation occurs throughout the world. For example, 2 different ethnic groups from genetically homogeneous regions in Japan have as much as a 20% difference in the prevalence of adenomas in people aged 50 years.

Race-related demographics

Although substantial variations in adenoma risk occur among different populations, race itself does not appear to be an independent determinant of risk. Dietary and environmental factors may have a role in explaining some of the differences observed throughout the world; for instance, a larger waist circumference in Japanese women and metabolic syndrome in Japanese men was associated with a higher risk of advanced neoplasia. [31] Similarly, blacks in New Orleans have a high risk for adenomas, while South African rural blacks are at low risk for developing adenomas.

The Veterans Administration Colonoscopy Screening study [32] found that African Americans had a higher risk of polyps larger than 9 mm (8% vs 6% among whites). This difference was especially pronounced in African American women compared with white women. African Americans older than 60 years are also more likely to have proximal colon adenomas, more likely to develop colorectal cancer (CRC) at a younger age, and may have a higher CRC-associated mortality rate.

Sex-related demographics

A meta-analysis of 17 studies including over 900,000 patients showed a pooled relative risk for advanced colonic neoplasia of 1.83 (95% confidence interval, 1.69-1.97) for men compared with women. The positive association between sex and advanced neoplasia was significant across all age groups from 40 years to older than 70 years. [33]

Age-related demographics

The prevalence of adenomas increases progressively with age. Adenomas are uncommon in people younger than 30 years unless associated with a significant family history or familial syndrome. Most studies suggest that sporadic adenoma prevalence begins to increase substantially in people aged 40-50 years and continues to increase through age 80 years. [30]

Prognosis

Almost all cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) arise from an adenoma; excision of adenomas reduces the incidence of CRC. Adherence to guidelines for screening and surveillance of adenomas is expected to substantially reduce the risk of developing colon cancer.

Mortality/Morbidity

Except for the rare adenoma that causes a clinically significant hemorrhage or obstruction, morbidity and mortality are primarily related to the carcinoma that can arise from an adenoma.

Complications

The primary complication associated with adenomas is the potential development of colorectal cancer. Less than 5% of all adenomas progress to cancer. The risk of progression to cancer rises with increasing size, villous component, and degree of dysplasia.

Complications of colonoscopy include perforation, bleeding and sedation-related complications. A diagnostic colonoscopy carries a complication risk of about 0.1%; polypectomy substantially increases the risk of complications to up to 0.2% for perforation and 1% for bleeding.

Patient Education

A sustained public awareness campaign emphasizing the importance of early detection of adenomas in the prevention of CRC has been supported by all major gastroenterology associations.

The patient must be aware that there is a 6% to 12% miss rate for adenomas that are 1 cm or larger; the miss rate for smaller adenomas is up to 25%. It is wise to include this information in the informed consent process.

-

Endoscopic view of a pedunculated polyp.

-

Endoscopic view of a sessile polyp.

-

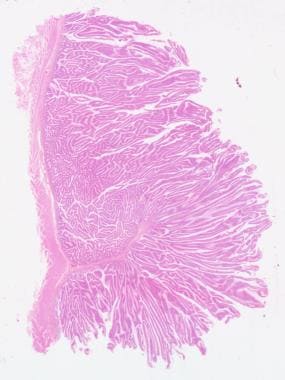

Tubular adenoma, low-power view. Courtesy of George H. Warren, MD.

-

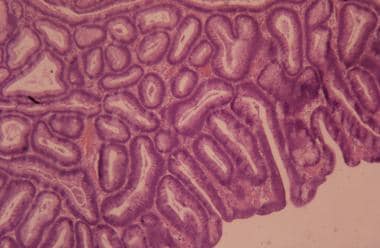

Villous adenoma, low-power view. Courtesy of George H. Warren, MD.

-

High-power view of adenomatous polyp with low-grade dysplasia. Courtesy of George H. Warren, MD.

-

Villous adenoma with grade IV invasive carcinoma. Courtesy of George H. Warren, MD.