Practice Essentials

Hormone therapy (HT) involves the administration of synthetic estrogen and progestogen to replace a woman's depleting hormone levels and thus alleviate menopausal symptoms. However, HT has been linked to various risks; debate regarding its risk-benefit ratio continues.

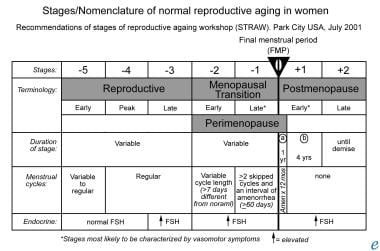

The image below depicts the stages and nomenclature of normal reproductive aging in women.

Signs and symptoms

The spectrum and intensity of perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms vary greatly due to the effect of decreased circulating levels of estrogen on various organ systems.

The most common presentation of menopause (60% of postmenopausal women) is hypothalamically mediated vasomotor instability leading to hot flashes (hot flushes), sweating, and palpitations. Other common presenting symptoms include the following:

-

Irregular menstrual cycles

-

Urogenital symptoms: Vaginal dryness, soreness, superficial dyspareunia, urinary frequency and urgency

-

Psychological symptoms: Mood changes, insomnia, depression, anxiety

Menopausal effects

Menopause has the following physiologic effects:

-

Vasomotor system: Vasomotor instability

-

Urogenital system: Atrophy and thinning of the mucosal lining of the urethra, urinary bladder, vagina, and vulva; loss of vaginal elasticity and distensibility; reduced vaginal secretions; degeneration of subepithelial vasculature and the supporting subcutaneous connective tissue

-

Bone metabolism: Progressive bone loss

-

Cardiac function: Increased susceptibility to heart disease

Forms of HT

HT can be prescribed as local (creams, pessaries, rings) or systemic therapy (oral drugs, transdermal patches and gels, implants). Hormonal products available in such preparations may contain the following ingredients:

-

Estrogen alone

-

Combined estrogen and progestogen

-

Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM)

-

Gonadomimetics, such as tibolone, which contain estrogen, progestogen, and an androgen

The estrogens most commonly prescribed are conjugated estrogens that may be equine (CEE) or synthetic, micronized 17β estradiol, and ethinyl estradiol. The progestins that are used commonly are medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and norethindrone acetate.

The various schedules of hormone therapy include the following:

-

Estrogen taken daily

-

Cyclic or sequential regimens: Progestogen is added for 10-14 days every 4 weeks

-

Continuous combined regimens: Estrogen and progestogen are taken daily

HT indications, contraindications, and adverse effects/risks

Indications

Indications for hormone therapy can be symptomatic or preventive. However, the application of HT to prevent sequelae of menopause is controversial, although some consensus has been reached regarding the use of HT to relieve symptoms.

The following are common clinical indications for prescribing HT:

-

To relieve vasomotor symptoms

-

To improve urogenital symptoms (long-term therapy is required)

-

To prevent osteoporosis

Contraindications

No absolute contraindications of HT have been established. However, relative contraindications exist in certain clinical situations, such as patients with the following findings:

-

A history of breast cancer*

-

A history of endometrial cancer*

-

Porphyria

-

Severe active liver disease

-

Hypertriglyceridemia

-

Thromboembolic disorders

-

Undiagnosed vaginal bleeding

-

Endometriosis

-

Fibroids

* Note that many clinicians do not prescribe HT for women with a previous history of breast or endometrial cancer.

Adverse effects and risks

Possible transient adverse effects are as follows:

-

Nausea

-

Bloating, weight gain (equivocal finding), fluid retention

-

Mood swings (associated with use of relatively androgenic progestogens)

-

Breakthrough bleeding

-

Breast tenderness

Potential risks of HT in postmenopausal women include the following:

-

Breast cancer: Use of combined HT; study results inconsistent, but emerging consensus of slightly increased risk for breast cancer similar to that associated with natural late menopause—comes into effect after at least 5 years of continuous HT [1]

-

Endometrial cancer [2] and uterine hyperplasia and cancer: Use of HT based on unopposed estrogen

-

Thromboembolism: Use of combined or estrogen-only HT

-

Biliary pathology: Use of estrogen only or combined estrogen/progestogen HT [3]

Evaluation for hormone therapy

All candidates for HT should be thoroughly evaluated with a detailed history and complete physical examination for a proper diagnosis and identification of any contraindications.

Baseline laboratory and imaging studies before administering HT include the following:

-

Hemography

-

Urinalysis

-

Fasting lipid profile

-

Blood sugar levels

-

Serum estradiol levels: In women who will be prescribed an implant and in those whose symptoms persist despite use of an adequate dose of a patch or gel

-

Serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels: To monitor women taking oral preparations for symptomatic control, especially those with premature menopause

-

Ultrasonography: To measure endometrial thickness and ovarian volume

-

Electrocardiography

-

Papanicolaou test

-

Mammography: Performed once every 2-3 years and annually after the age of 50 years

Endometrial sampling is not required in routine practice. However, the presence of abnormal bleeding before or during HT should prompt consideration of ultrasonography to check endometrial thickness (cutoff, < 4 mm), followed by outpatient Pipelle sampling and hysteroscopy. In women with a tight cervix, formal hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage under general anesthesia are advised.

Overview

The reproductive years of a woman’s life are regulated by production of the hormones estrogen and progesterone by the ovaries. Estrogen regulates a woman's monthly menstrual cycle and secondary sexual characteristics (eg, breast development and function). In addition, it prepares the body for fertilization and reproduction. Progesterone concentrations rise in a cyclical fashion to prepare the uterus for possible pregnancy and to prepare the breasts for lactation.

Toward the end of her reproductive years when a woman reaches menopause, circulating levels of estrogen and progesterone decrease because of reduced synthesis in the ovary. Hypoestrogenism during menopause can lead to several symptoms, the severity of which can vary widely.

Hormone therapy (HT) involves the administration of synthetic estrogen and progestogen. HT is designed to replace a woman's depleting hormone levels and thus alleviate her symptoms of menopause. However, HT has been linked to various risks, and debate regarding its risk-benefit ratio continues.

Symptoms and Effects of Menopause

Menopause is the time in a woman’s life when menstruation ceases, signaling the end of her reproductive ability. The timing of menopause varies widely, but this event often occurs naturally in women in the fourth or fifth decades of life, at a mean age of 51 years. Certain medical or surgical conditions may induce the cessation of menses before this age. If menopause occurs before the age of 40 years, it is considered premature.

The STRAW (Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop) classification proposed by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine depicts the natural transition in a female's life from the reproductive years to the time of menopause.

The reproductive years are divided into early, peak, and late and are characterized by regular menstrual cycles (although they may be variable during the early phase). This is followed by the stage of menopausal transition, which earlier on is characterized by a variable cycle length that is more than 7 days different from normal. During the latter stages of this transition phase, women experience intervals of amenorrhea of more than 60 days. When this duration of amenorrhea lasts for up to 12 months, it is classified as postmenopause. The stage of perimenopause spans from the beginning of the stage of menopause transition up until the completion of 1 year following the final menstrual period.

The spectrum and intensity of symptoms that women experience during perimenopause and menopause vary greatly. Symptoms result from the effect of decreased circulating levels of estrogen on various organ systems. Hypothalamically mediated vasomotor instability leading to hot flashes (hot flushes), sweating, and palpitations is the most common presentation of menopause. These symptoms occur in more than 60% of postmenopausal women.

Common presenting symptoms of menopause

Common presenting symptoms of menopause include the following:

-

Irregular menstrual cycles

-

Sweating

-

Hot flashes (hot flushes)

-

Palpitations

-

Vaginal dryness

-

Soreness

-

Superficial dyspareunia

-

Urinary frequency and urgency

-

Mood changes

-

Insomnia

-

Depression

-

Anxiety

-

Effects on the vasomotor system

Effects on the vasomotor system

Vasomotor instability is the most common presenting symptom noted in postmenopausal women. Its exact cause is not yet known, but it is believed to be mediated at the level of the hypothalamus. Estrogen plays a role in thermoregulation by modulating the levels of neurotransmitters in the CNS. During menopause, diminished levels may lead to instability in the normal concentration of these transmitters, which manifests as hot flashes (hot flushes), night sweats, and excessive perspiration.

Effects on the urogenital system

Estrogen plays an important role in maintaining the normal physiology of the urogenital system. Decreased circulating levels of this hormone during menopause are associated with a change in the microenvironment of the urogenital organs. The mucosal lining of the urethra, urinary bladder, vagina, and vulva shows atrophic changes and becomes thinned. The vagina loses its elasticity and distensibility and becomes short and narrow. Normal secretions from the vaginal glands are reduced. The subepithelial vasculature and the supporting subcutaneous connective tissue also demonstrate degenerative changes over time.

As endogenous estrogen levels decrease, so does the production of epithelial-cell glycogen. This alteration changes the normal alkaline milieu of the vagina and bladder. The resultant acidic pH alters the local flora of the vagina and urinary bladder, allowing for their colonization by gram-negative bacteria and fungi and predisposing the woman to recurrent urinary tract infections.

Effect on bone metabolism

Bone mass steadily increases during childhood and adolescence and reaches a plateau in the third decade of life. Men achieve a higher peak bone mass than women do. As a subsequence, age-related bone loss is further governed by an interplay of multiple factors, particularly sex, family history, diet, and exercise. Women are more susceptible than men, and the low estrogen levels of menopause can accelerate the progressive bone loss, particularly in the first 5 years after menopause. This situation predisposes postmenopausal women to develop osteoporosis and osteoporosis-related fractures. A 50-year-old woman has a 40% lifetime risk of having a fragility fracture, which typically occurs in the femoral neck, vertebra, or distal forearm. [4]

Effect on cardiac function

At menopause, women begin to lose their natural resistance to heart disease (see Coronary Artery Disease and Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis). By the age of 65 years, their risk of having a heart attack equals that of men. [5] This increased susceptibility to heart disease is attributed to the reduction in the beneficial effects of estrogen on plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels, insulin sensitivity, the distribution of body fat, coagulation, fibrinolysis, and endothelial function.

Serum fibrinogen and plasma activator inhibitor (PA1) concentrations are powerful predictors of cardiac disease in men and women. [6] Evidence suggests that menopause is associated with heightened serum levels of fibrinogen and PA1.

All of the factors just discussed contribute to the increased risk for morbidity and mortality in postmenopausal women.

Brief History and Forms of Therapy

Hormone therapy (HT) is treatment with prescription hormonal medications—namely, estrogen alone or estrogen in combination with progestogen—to restore a woman's declining hormone levels.

Brief history of hormone therapy

Estrogen has been used to treat symptoms of menopause since the 1950s and 1960s. By 1975, estrogen had become one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States.

In the mid-1970s, studies demonstrated that postmenopausal women who used estrogen therapy alone had a significantly increased risk of endometrial cancer. Researchers found that adding progestogen to estrogen provided protection against uterine cancer. As a result, progestogen was added to HT regimens prescribed for women with an intact uterus.

Over the years, HT became a popular treatment, as it was recommended not only for treating menopausal symptoms but also for providing long-term protection against osteoporosis and related fractures, heart disease, and even Alzheimer disease. However, in 2002, the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), a large-scale study conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), was stopped early because evidence linked HT to a slightly increased risk of stroke, heart disease, and breast cancer. As a result of this study, many women turned to non–US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved compounded bioidentical HT (CBHT), or natural HT, as a perceived safer alternative. [7] However, no clear evidence suggests that custom CBHT formulas are safer or more effective than FDA-approved HT products. Physicians may wish to use custom formulas for those patients who cannot tolerate standard HT. [8]

Forms of hormone therapy

HT can be prescribed as local or systemic therapy, as follows:

-

Local preparations - Creams, pessaries, rings

-

Systemic formulations - Oral drugs, transdermal patches and gels, implants

Liver bypass of the hormones is achieved with transdermal preparations and implants, which help to ensure predictable and optimal serum levels.

Hormonal products available in the preparations listed may contain the following ingredients:

-

Estrogen alone

-

Combined estrogen and progestogen

-

Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM)

-

Gonadomimetics, such as tibolone, which contain estrogen, progestogen, and an androgen

The various schedules of hormone therapy include the following:

-

Estrogen taken daily

-

Cyclic or sequential regimens in which progestogen is added for 10-14 days every 4 weeks

-

Continuous combined regimens in which estrogen and progestogen are taken daily

The estrogens most commonly prescribed are conjugated estrogens that may be equine (CEE) or synthetic, micronized 17β estradiol, and ethinyl estradiol. The progestins that are used commonly are medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and norethindrone acetate.

The dosage varies but the most commonly prescribed HT is combined estrogen and progestin in the form of 0.625 mg/d CEE with 2.5 mg/d MPA in women with an intact uterus. Lower dose preparations that contain 1.5 mg/d of MPA with either 0.45 mg or 0.3 mg/d of CEE are becoming increasingly popular.

Estrogen is used alone in women who have undergone hysterectomy. Treatment should be initiated with the lowest possible dosage and then titrated based on clinical response.

SERMS are a class of nonhormonal drugs that selectively mimic or antagonize the effect of estrogen at various target organ sites. They have beneficial effects on bone and cholesterol metabolism and can be offered as an alternative to traditional HT for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Indications for Hormone Therapy

Indications for hormone therapy can be symptomatic or preventive. Although some consensus has been reached regarding the use of HT to relieve symptoms, the application of HT to prevent sequelae of menopause is controversial. Common clinical settings in which HT is prescribed are described below.

Vasomotor symptoms

The main indication for HT is relief of the most common symptoms of menopause, namely hot flushes, sweating, and palpitations. The effectiveness of this treatment was proven in placebo-controlled randomized studies. [9]

Urogenital symptoms

Both topical and systemic estrogens have been shown to improve the menopausal symptoms of vaginal dryness, superficial dyspareunia, and urinary frequency and urgency. Achievement of these beneficial effects require long-term therapy. Symptoms commonly recur after HT is stopped. [10]

Osteoporosis

One in 3 postmenopausal women develops osteoporosis. [4] HT is commonly prescribed to help prevent this condition, and HT appears to be particularly effective if it is started during the first 5 years after the onset of menopause. Women who have a decreased bone mineral density and those with a known history of osteoporotic fractures benefit from HT. Women with premature menopause also benefit from the bone-protective benefit of HT. However, they may lose protection after they stop taking hormones.

Absolute risks based on results from the WHI trial indicated that 5 years of combined hormone therapy reduced the incidence of hip fractures by about 1 case per 1000 women younger than 70 years and by about 8 cases per 1000 women aged 70-79 years.

Contraindications to Hormone Therapy

No absolute contraindications of hormone therapy have been established. However, HT is relatively contraindicated in certain clinical situations, such as patients with the following findings:

-

A history of breast cancer

-

A history of endometrial cancer (see Uterine Cancer and Endometrial Carcinoma)

-

Porphyria

-

Severe active liver disease

-

Thromboembolic disorders (see Deep Venous Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism)

-

Undiagnosed vaginal bleeding (see Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding)

-

Fibroids

Note that many clinicians do not prescribe HT for women with a previous history of breast or endometrial cancer.

Pretreatment Evaluation

All patients who are candidates for hormone therapy should be thoroughly evaluated by means of a detailed history and complete physical examination. The objectives are making a proper diagnosis and identifying any contraindications.

Components of a full history are as follows:

-

Personal history

-

Social history

-

Obstetric history

-

Gynecologic history

-

Menstrual and sexual history

-

Previous medical history (eg, of diabetes, hypertension, jaundice, gallstones, hepatic disease, thrombosis)

-

Previous surgical interventions

-

Menopausal symptoms

-

Psychiatric problems

-

Skeletal symptoms

-

Psychomotor symptoms

-

Cognitive performance

Components of the physical examination include the following:

-

Height measurement

-

Weight measurement

-

Determination of an obesity index (see Obesity)

-

Blood pressure measurement (see Hypertension)

-

Breast examination

-

Abdominal examination

-

Pelvic examination

-

Rectal examination

Required baseline investigations are as follows:

-

Hemography

-

Urinalysis

-

Evaluation of the fasting lipid profile

-

Measurement of blood sugar levels

-

Electrocardiography

-

Papanicolaou test

-

Ultrasonography to measure endometrial thickness and ovarian volume

-

Mammography, which is performed once every 2-3 years and annually after the age of 50 years (see Mammography - Computer-Aided Detection)

-

Determination of serum estradiol levels in women who will be prescribed an implant and in women whose symptoms persist despite use of an adequate dose of a patch or gel

-

Determination of serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels: FSH values may be used to monitor women who are taking oral preparations for symptomatic control, especially those with premature menopause.

-

Endometrial sampling: This test is not required in routine practice. If abnormal bleeding is present before or during HT, ultrasonography is recommended to check endometrial thickness (cutoff, < 4 mm), followed by outpatient Pipelle sampling and hysteroscopy. In patients with a tight cervix, formal hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage under general anesthesia are advised.

Adverse Effects and Risks of Hormone Therapy

Transient adverse effects

Hormone therapy is associated with certain innocuous adverse effects that are transient and that usually resolve. The patient should be forewarned to prevent their discontinuation of therapy.

Possible adverse effects are as follows:

-

Nausea

-

Bloating

-

Weight gain (equivocal finding)

-

Fluid retention

-

Mood swings (which are associated with use of relatively androgenic progestogens)

-

Breakthrough bleeding

-

Breast tenderness

No consensus has been established regarding the risk-benefit ratio of HT. Results of various trials have failed to resolve the ongoing controversies.

In 1991, the NIH launched the WHI, the largest study of its kind. This initiative involved double-blind, randomized, controlled trials involving about 161,000 healthy postmenopausal women aged 50-79 years. Three clinical trials, conducted at the same American centers, were designed to test the effects of menopausal hormone therapy, diet modification, and calcium and vitamin D supplementation on heart disease, osteoporotic fractures, and breast and colorectal cancer. One study arm consisted of about 10,000 women who had undergone a hysterectomy; they received estrogen alone. In the other arm, about 16,000 women received combined estrogen and progestogen. The study was to have continued until 2005, but it was halted early in 2002 because investigators observed an increased risk of breast cancer and because the overall risks of the hormones outweighed their benefits across the 3 decades studied.

Reanalysis of the WHI data by age cohort showed that the risks of breast cancer, stroke, and heart disease were not increased in the fifth decade but rose in the sixth and seventh. The breast cancer risk was apparent in women exposed to HT before they entered the WHI study after a washout period but not in those who had never received HT.

Another landmark investigation, the Million Women Study was an observational study performed in the United Kingdom. It has provided information about a diverse range of HT regimens, with the exception of vaginal preparations, in women aged 50-64 years (mean age, 57 y) who attended the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP).

A prospective cohort study of 108,844 postmenopausal US women found an association between hormone therapy and increased risk of ulcerative colitis. The risk of UC increased with longer duration of hormone use and decreased with time since continuation. There did not appear to be an increased risk of Crohn's disease. [11]

Hormone therapy and breast cancer

Although studies have been inconsistent, an emerging consensus appears to suggest that HT may slightly increase the risk for breast cancer. This risk is similar to that associated with natural late menopause, and it comes into effect after at least 5 years of continuous HT. [1] The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer significantly increases with current long-term HT when it is started in women aged 50 years or older (relative risk, 1.35). Such an effect is not seen in women who start HT early for premature menopause. This observation indicates that it is the duration of lifetime sex hormone exposure that is relevant.

Hormone therapy regimens

The WHI study demonstrated that the risk for breast cancer was 8 cases per 10,000 women per year after 5 years of therapy. This study did not show an increased risk among women who were using only estrogen. It did show a slightly reduced risk; however, the difference was not statistically significant.

These WHI findings contrast with observations from the Million Women Study, which also showed an increased risk of breast cancer in women who took estrogen alone or tibolone. However, the risk was elevated in those who received combined therapy. Neither the route nor the pattern of administration of HT had an effect on the risk of breast cancer.

A randomized, placebo-controlled study by the WHI examined the incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women receiving estrogen plus progestin. [12] The study included 16,608 postmenopausal women aged 50-79 years who had not undergone a hysterectomy. The study found that estrogen plus progestin was associated with more invasive breast cancers compared with placebo (385 cases vs 293 cases), and more deaths from all causes occurred after a breast cancer diagnosis among women who received estrogen plus progestin compared with placebo (51 vs 31).

Mammographic density

Mammographic density increases in about 25% of women who use either cyclical or continuous combined HT, as evidenced in a randomized placebo-controlled study. [13] The degree of density increase is 5%. Unopposed estrogen and tibolone have no significant effect.

Results of the Million Women Study contrasted with evidence from placebo-controlled studies, showing that both unopposed and combined HT increased density. Other observational evidence suggested that the cessation of HT for a few weeks before mammography may improve accuracy of the imaging study.

Survival of patients with breast cancer who are receiving hormone therapy

Survival of patients with breast cancer who are receiving HT is difficult to measure reliably. Overall, observational data suggest that HT has no significant effect on survival compared with no HT.

Obesity exerts a modifying effect on the association between hormone use and breast cancer. The risk of breast cancer increases in association with hormone use for lean women but not for heavy women. Adipose tissue is the primary source of endogenous estrogen after menopause, and circulating levels of estrogen are considerably elevated in obese postmenopausal women. Therefore, exogenous estrogen may have less of an effect on estrogen availability in heavy women than in lean women.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed a sharp decline in the rate of new cases of breast cancer in 2003 in the United States. [14] This change may have been related to a national decline in the use of HT. The decrease occurred only in women older than 50 years and was more evident in women with cancers that were estrogen-receptor positive, ie, tumors that need estrogen to grow and multiply. Because the analysis was based on population statistics, the finding did not prove a link between HT and the incidence of breast cancer. This link can be proven only with randomized controlled trials.

A cohort study by McVicker et al found that vaginal estrogen therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) did not increase the risk of breast cancer–specific mortality. The study included 49,237 women with breast cancer, and 5% used vaginal estrogen after cancer was diagnosed. [15] A study by Agrawal et al found no increase in the risk of breast cancer recurrence within 5 years in women with a history of breast cancer who used vaginal estrogen therapy for GSM. [16]

Hormone therapy and endometrial cancer

In 1975, Zeil and Finle proved the relationship between the administration of exogenous estrogens and an increased incidence of endometrial cancer. [2] More recently, evidence from randomized controlled studies showed a definite association between HT and uterine hyperplasia and cancer. HT based on unopposed estrogen is associated with this observed risk, which is unlike the increased risk of breast cancer linked with combined rather than unopposed HT.

Continuous combined regimens have not been associated with an increased risk. [17] However, cyclical regimens—even ones involving 10-14 days of progestogens per month—do increase the risk after 5 years of usage.

Hormone therapy and thromboembolism

Various studies have shown concordance in the observation of an increased risk of thromboembolism with HT. The WHI study demonstrated combined HT increased the risk of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in 15 per 10,000 women per year. The risk of venous thrombosis increased for women given an estrogen-only regimen, but their risk of developing pulmonary emboli was not statistically significant.

An underlying coagulopathy increases the occurrence of thromboembolic complications. Transdermal HT may be associated with a lowered risk.

Hormone therapy and biliary pathology

Cholelithiasis is common among postmenopausal women, as increasing age and obesity are considered risk factors for the condition. In various studies including the WHI, this risk further increased in postmenopausal women receiving HT. The annual incidence for any gallbladder event was 78 events per 10,000 person-years for women taking estrogen-only preparations versus 47 events per 10,000 person-years for placebo. [3] By comparison, rates were 55 per 10,000 person-years for combined estrogen and progestogen versus 35 events per 10,000 person-years for placebo.

Uncertain Effects of Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease

The incidence of cardiac disease is heightened in postmenopausal women. This finding has been linked to a causative pathogenic role of ovarian hormone deficiency.

When the concept of HT was initially introduced, it was believed that replacing ovarian hormones would reduce the observed increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease. However, this expected result has not been unequivocally demonstrated in various trials over the years.

The WHI study revealed an increased annual risk of heart attacks of 7 per 10,000 women who took combined therapy as opposed to women who took estrogen alone, in whom no significant difference was noted. Subsequent re-analysis showed similar results for breast cancer, demonstrating no increased risk in the fifth decade, though the risk rose with advancing age.

Two important clinical trials have been conducted to examine the relationship between cardiac disease and HT: the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestogen Interventions Trial (PEPI) and the Heart and Estrogen-Progestogen Replacement Study (HERS).

PEPI investigators looked at the effect of estrogen alone and combination therapies on bone mass and key risk factors for heart disease. They found generally positive results, including a reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol by both types of therapy.

HERS researchers tested whether estrogen plus progestogen would prevent a second heart attack or other coronary event in a secondary prevention study. They found no reduction in risk with such hormone therapy over 4 years. In fact, treatment increased the women’s risk for having a heart attack during the first year of hormone use. The risk declined thereafter. In the HERS follow-up study, participants were monitored for about 3 more years. This study showed no lasting decrease in heart disease from estrogen plus progestogen.

The widely discordant results might have been due to a few important factors that govern the effect of HT on the participant's cardiovascular status. These factors are as follows:

-

Time to the start of HT after menopause

-

Associations related to estrogen and progestogen

-

Body mass of postmenopausal women

-

Underlying risk factors for cardiac disease

After menopause, the cardioprotective effect of estrogen is lost, but the detrimental procoagulant effects persist. If HT is started early in postmenopausal women, the cardiac endothelium is still responsive to estrogens, and the procoagulant effects may be buffered. On the contrary, in elderly postmenopausal women, HT may not show a similar benefit. In these women, ovarian hormones have either no effect or a detrimental effect because of the predominance of the procoagulant effects over the vasoprotective effects.

Women who already had a low risk of dying from coronary heart disease by virtue of their lean body mass have the greatest decrease in risk with estrogen use, as compared with women whose body mass index is >30 kg/m2.

A meta-analysis found strong evidence that treatment with hormone therapy in post-menopausal women overall, for either primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease events, has little if any benefit and causes an increase in the risk of stroke and venous thromboembolic events. [18, 19]

Ovarian cancer

In various studies, effects of postmenopausal hormones on ovarian cancer risk have been inconsistent. Some researchers reported an increased risk with estrogen use, whereas others reported either no effect or a protective one. This confounding of results has been attributed to the fact that ovarian cancer is a rare disease and that numbers of patients were insufficient in the studies that have tried to elucidate the relationship.

A large prospective study showed that postmenopausal estrogen use for 10 years or longer was associated with increased risk of ovarian cancer mortality. [20] Swedish investigators reported that estrogen use alone and estrogen-progestogen used sequentially (progestogen used on average 10 d/mo) may be associated with an increased risk for ovarian cancer. [21] In contrast, continuous estrogen-progestogen (progestogen used on a mean of 28 d/mo) seemed to confer no increased risk of ovarian cancer. The WHI study demonstrated that continuous combined HT may slightly increase the risk of ovarian cancer.

In the NCI Study of Hormone Therapy and Ovarian Cancer, researchers examined data from a large study that included 23,722 women who had hysterectomies and 73,483 women with intact uteri. [22] Their objective was to learn whether menopausal hormone use affected the risk of ovarian cancer. The risk of ovarian cancer was higher in women who received menopausal hormone therapy than in women who never used such therapy. However, the increased risks differed by hormone therapy formulation and regimen and varied according to the women's hysterectomy status.

In women who have undergone a hysterectomy, the use of estrogen alone for more than 10 years was linked to an increased risk of ovarian cancer. This increase in risk was not observed in women who took HT for less than 10 years.

In women with intact uteri, 5 or more years of sequential, but not continuous, estrogen plus progestogen was positively associated with ovarian cancer. This increased risk was also demonstrated in the Million Women Study.

Dementia and cognition

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for dementia, and most of the risk is attributed to Alzheimer disease, cerebrovascular disease, or a combination of both. The decrease in the supply of neuronal growth factors with age appears to mediate neural pathology. Estrogen is believed to be one such growth factor. It enhances cholinergic neurotransmission and prevents oxidative cell damage, neuronal atrophy, and glucocorticoid-induced neuronal damage.

In theory, HT in postmenopausal women should prevent and help treat dementia and related disorders. However, various studies have failed to provide a consensus on this aspect. This lack is largely because of issues of selection bias, as well as extreme heterogeneity in study participants, treatments, and cognitive function tests applied, and doses of HT.

Early studies showed that estrogens may delay or reduce the risk of Alzheimer disease, but it may not improve established disease. [23]

Contrasting new findings from a memory substudy of the WHI showed that older women taking combination hormone therapy had twice the rate of dementia, including Alzheimer disease, compared with women who did not. The research, part of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) revealed a heightened risk of dementia in women aged 65 years or older who took combination HT. This risk increased in women who already had relatively low cognitive function at the start of treatment. [24]

Authors of the Cache County Study were the first to propose the window-of-opportunity theory. [25] The risk of Alzheimer disease varied with duration of drug use. Previous use of HT was associated with a decreased risk. However, no benefit was apparent unless current HT was used for longer than 10 years.

At present, no definite evidence supports the use of HT to prevent or improve cognitive deterioration.

Guidelines

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issued the following guidelines on menopause that recommend that physicians [26, 27] :

-

Offer women hormone-replacement therapy (HRT) for hot flushes and night sweats after discussing risks and benefits.

-

Consider HRT to ease low mood that occurs as a result of menopause and consider cognitive behavioral therapy to alleviate low mood or anxiety.

-

Explain that estrogen-only HRT has little or no increase in the risk of breast cancer, while HRT with estrogen and progestogen can be associated with an increase in the risk of breast cancer, but any increased risk reduces after stopping HRT. Specifically, it says there will be 17 more cases of breast cancer per 1000 menopausal women in current HRT users over 7.5 years (compared with no HRT)

-

Understand that HRT does not increase cardiovascular disease risk when started in women aged under 60 years and it does not affect the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. Also ensure that women with cardiovascular risk factors are not automatically excluded from taking HRT.

-

Refer women to a menopause specialist if there's no improvement after trying treatments.

The International Menopause Society issued guidelines on menopausal hormone therapy that include the following recommendations [28, 29] :

-

Hormone therapy continues to be the most effective treatment for menopause symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms and urogenital atrophy, according to the International Menopause Society.

-

Menopausal hormone therapy, including tibolone and the combination of conjugated equine estrogens and bazedoxifene (CE/BZA), is the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause.

-

If menopausal hormone therapy is contraindicated or not desired, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine, escitalopram, venlafaxine, and desvenlafaxine may be considered, as well as gabapentin.

-

Menopausal hormone therapy can be initiated in postmenopausal women at risk of fracture or osteoporosis before 60 yr of age or within 10 yr after menopause.

A December 2017 statement by the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against using combined estrogen and progestin for the primary prevention of chronic conditions for most postmenopausal women with an intact uterus. The statement also adds that estrogen alone has no net benefit for the primary prevention of chronic conditions for most postmenopausal women who have had a hysterectomy. [30]

In 2017, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) issued an updated position statement on hormone therapy. [31] Among the recommendations are the following:

-

Treatment should be individualized to determine the most suitable type of hormone therapy, dose, formulation, route of administration, and duration of use

-

For women who are younger than 60 years or who are within 10 years of menopause onset and have no contraindications, the benefits of hormone therapy for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms and the prevention of bone loss and fracture tend to outweigh the risks

-

For women aged 60 years and older and those who start hormone therapy more than 10 years from menopause onset, the greater absolute risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and dementia make the benefit-risk ratio less favorable

-

For women who have genitourinary symptoms that resist over-the-counter agents and who have no indications for systemic hormone therapy, low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy or other therapies are recommended

In 2022, NAMS affirmed these recommendations in an updated position statement. [32]

Summary

Estrogens provide valuable therapy for many women but may pose serious risks. Therefore, physicians should communicate with postmenopausal women who are using or who may be using estrogen or estrogen with progestogen to determine whether the benefits outweigh the risks in their particular case.

Estrogen-containing products are the most effective approved therapies for managing hot flashes and symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy. They are also good for bone protection.

Estrogens and progestogens should be used at the lowest dosages and for the shortest durations necessary to achieve symptomatic relief. Dosages and durations may vary greatly among individual patients. Low-dose regimens may lower the risk of serious adverse effects. The overriding maxim is that treatment must always be individualized and reviewed.

In general, women using HT are most likely to have a high level of education, to engage in physical exercise, and to have a high intake of dietary fiber. Therefore, caution is required when one interprets the results of observational studies of the effects of HT, as selection bias may be in operation.

Questions & Answers

Overview

What is the hormonal response to menopause?

What is menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

What are the signs and symptoms of perimenopausal and menopause?

What are the physiologic effects of menopause?

How is menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) administered?

When is menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) indicated?

What are the contraindications for menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

What are the possible transient adverse effects of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

What are the possible long-term risks of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

What are the most common presenting symptoms of menopause?

What is the STRAW classification of reproductive aging?

What causes the symptoms of menopause?

How does menopause affect the vasomotor system?

How does menopause affect the urogenital system?

How does menopause affect bone metabolism?

How does menopause affect cardiac function?

What is the goal of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

What is the evolution of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

What are the forms of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

When is menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) indicated?

What is the role of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in the prevention of osteoporosis?

What are the possible benign adverse effects of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect breast cancer risk?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect breast density?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect endometrial cancer risk?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect thromboembolism risk?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect gallbladder disease risk?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect cardiac disease risk?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect ovarian cancer risk?

How does menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affect the risk of dementia?

What are the USPSTF guidelines on menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

What is the role of estrogens in menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

How should menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) be dosed?

Which women are most likely to undergo menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT)?

-

Stages/nomenclature of normal reproductive aging in women.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Practice Essentials

- Overview

- Symptoms and Effects of Menopause

- Brief History and Forms of Therapy

- Indications for Hormone Therapy

- Contraindications to Hormone Therapy

- Pretreatment Evaluation

- Adverse Effects and Risks of Hormone Therapy

- Uncertain Effects of Hormone Therapy

- Guidelines

- Summary

- Questions & Answers

- Show All

- References