Approach Considerations

Perceptual speech evaluation by a qualified speech and language pathologist (SLP) with experience and expertise in cleft pathology is the mainstay of evaluation and ongoing treatment, in that the goal of therapy is the ability to communicate successfully using speech.

In patients with cleft palate, residual articulation abnormalities associated with hypernasality should be corrected after palate closure but before secondary surgery for velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD). Learned compensatory misarticulations must be addressed and corrected through focused intervention with a trained SLP. Early speech therapy results in increased speech accuracy and can help improve long-term outcomes. Parents can be trained to effectively deliver speech therapy to young children with cleft palate.

Van Demark and Hardin discussed the effectiveness of exclusive articulation therapy in children with cleft palate and noted less improvement and slower improvement than expected. [28] Ruscello reviewed nonsurgical palatal training procedures, such as articulation therapy, sucking and blowing exercises, electrical and tactile stimulation, speech appliances, and biofeedback techniques. [29] These techniques have never been demonstrated to be of any value, and all clinicians should make sure that their patients are not receiving ineffective speech therapy.

The prosthetic speech bulb is most useful in patients with little or no velopharyngeal motion. Velopharyngeal movement is essential to surgical success with a pharyngeal flap procedure or sphincter pharyngoplasty. Patients with little velopharyngeal movement are good candidates for prosthetic management. A velopharyngeal speech prosthesis can elevate the velum (lift), fill the residual velopharyngeal gap (obturator), or both (lift-orator). The nasal valve is another prosthetic option.

The primary indications for surgical intervention include structural defects of the velum and functional problems that result in poor or inconsistent velar closure.

One study that compared speech outcomes from prosthetic management with those from surgical management showed no difference for patients who complied with the prosthesis. [30] However, because nearly 30% of patients referred for prostheses did not comply, surgery was more efficacious overall.

Speech Therapy

Speech therapy improves velopharyngeal function in patients whose VPD is minimal or due to articulation errors and in postoperative patients. Compensatory articulation techniques secondary to VPD also can be corrected with speech therapy. However, in patients with a specific anatomic deficiency that precludes adequate closure of the velopharynx, speech therapy cannot replace surgery. Surgical management may also be necessary in cases where closure is possible but nasal speech persists with connected speech.

Upon completion of speech and language testing, the SLP determines if VPD and hypernasality are related to articulation errors or if the condition is phoneme-specific. If either is the case, the VPD usually is not related to structural abnormalities, and correction with speech therapy most likely is possible.

VPD also can be a result of decreased muscle tone in the oral musculature and soft palate. Decreased muscle tone can be observed on fiberoptic nasoendoscopy (FN) when the soft palate closes inconsistently or when closure appears slow in connected speech. A period of speech and language therapy focusing on improving overall oral motor skills and improving strength and elevation of the velum may be able to correct VPD in such cases. Speaking slowly and deliberately is another strategy to improve speech intelligibility.

Visual Feedback

In some children, especially those with hearing impairments, visual feedback can assist in therapy to improve VPD. Several devices are available to assist with this method. Simple tools (eg, a cold mirror or a paper paddle) can serve to show the patient when nasal escape occurs. Other devices are commercially available, such as the See-Scape, which is placed at the nose and causes a ball to rise when airflow is nasal rather than oral.

A more sophisticated method is the use of a nasometer, which graphically displays a ratio of oral sound energy to nasal sound energy. The visual readout can help the therapist and patient develop compensatory techniques to reduce nasalance. In older children, video-recorded nasopharyngoscopy has been used to achieve the same goals. The latter method has been shown to be effective in patients with VPD and cleft palate.

Nasal Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy is a palate-strengthening program completed 6 days a week for 8 weeks in the patient’s home. It is beneficial for patients whose VPD seems to be related to oral motor issues or velar weakness rather than to structural problems of the velum.

The CPAP equipment includes a nasal mask, which is attached to the patient. With the mask in place, the patient repeats a series of consonant-vowel combinations and sentences designed to cause the velum to open and close against air pressure from the nasal mask. CPAP pressures are increased on a regimented schedule, producing exercises similar to a weightlifting program for the soft palate.

The disadvantages of CPAP therapy are the high degree of regimentation and the need for cooperation and participation for up to 24 minutes, 6 days per week, which is difficult to achieve with young children. Wearing the nasal mask and speaking with nasal air pressure also can be frightening for some young children.

Studies of the efficacy of CPAP for hypernasality have demonstrated variable results; however, significant reductions in hypernasality are seen in some patients undergoing therapy. [31, 32] Further research is required to establish its effectiveness.

Prosthetic Management

In a small number of cases, prosthetic management may be the best solution for VPD. [33] Prostheses may be used as a temporary reversible trial; they can provide diagnostic information in cases of variable VPD where it is unclear whether surgery alone will significantly improve speech quality. They may be useful in some patients with a short, scarred velum or in other patients with a long, supple, paretic velum. Some authors have hypothesized that prostheses may stimulate neuromuscular activity, [34] though definitive proof for this hypothesis is lacking. [35]

The main types of prostheses include the following:

-

Palatal lift

-

Speech bulb/obturator

-

Nasal valve

Devices that include features of both lifts and obturators (so-called lift-orators) also exist.

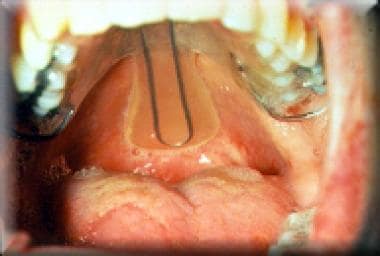

Palatal lifts (see the images below) are used when adequate palatal length exists but dynamic motion of the palate is poor as a consequence of neuromuscular etiologies. Palatal lifts reduce the distance the palate must traverse to produce adequate closure.

An obturator is usually necessary when the velum is short and scarred, and the ratio of velar length to nasopharyngeal depth is excessive, such as seen in some patients with repaired cleft palate. Obturators can substitute for tissue deficiency and are attached to the palate or teeth. In certain cases, the obturator can be downsized gradually so that the native tissue, if adequate in bulk, can strengthen over time and compensate for the decreasing obturator size.

A combined prosthesis (lift-orator) is useful when elevation of the velum alone is not sufficient to achieve closure. Such speech prostheses are fitted under endoscopic control by an interdisciplinary team that includes a prosthodontist, an SLP, and an endoscopist.

The nasal valve is an appliance fitted to each nostril. [36] A one-way valve on either side allows the patient to breathe in through the nose, but stops nasal airflow with exhalation or speech.

Surgical Therapy

As noted previously, the primary indications for surgical intervention include structural defects of the velum and functional problems that result in poor or inconsistent velar closure. Maximum benefit can be achieved when the surgical technique takes advantage of whatever native velopharyngeal function exists in the patient.

Information obtained during the objective evaluation via physical examination, FN, and multiview videofluoroscopy (VF) can greatly aid in determining the best way to make use of remaining velopharyngeal function. Some claim that successful outcomes in fact depend on matching the functional capability of the patient with the surgical procedure. Others have disputed this claim, reporting that there is no difference in outcomes regardless of surgical technique or preoperative sphincter characteristics.

Four patterns of velopharyngeal closure (VPC) have been described on the basis of FN and VF: coronal, sagittal, circular, and circular with the Passavant ridge. (See Pathophysiology.) The type of closure pattern is determined by the relative contribution of the palate and lateral pharyngeal walls to closure of the velopharyngeal sphincter. Determination of a patient’s predominant VPC pattern (see the videos below) directs the surgeon to the most appropriate treatment for the patient.

The four main surgical approaches to velopharyngeal corrective surgery are as follows [37, 38] :

-

Palatoplasty

-

Pharyngeal flap

-

Sphincter pharyngoplasty

-

Posterior pharyngeal wall augmentation

Go to Surgical Treatment of Velopharyngeal Dysfunction for complete information on this topic.

Palatoplasty

Palatal procedures most often include the Furlow palatoplasty, which involves a double Z-plasty lengthening of the palate. This technique appears to work best when the orientation of the palatal levator musculature is sagittal or when a small preoperative velopharyngeal gap size is noted.

Pharyngeal flap

The pharyngeal flap is the preferred surgical approach in patients with good lateral pharyngeal wall motion who have a persistent central gap resulting from poor palatal motion, as is common following repair of a cleft palate. The procedure aims to develop a central flap of tissue to obturate the midline of the pharyngeal port and decrease the degree of air escape into the nasal cavity. [39, 40, 41, 42, 43]

Schoenborn first reported this procedure in 1876 when he described an inferiorly based posterior wall flap sutured to the nasal surface of the soft palate. He later modified this procedure by using a superiorly based flap when he found that an inferiorly based flap tended to contract and tether the palate downward over time, worsening the patient’s velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI).

The flap is raised down to the level of the prevertebral fascia, creating a tissue flap of superior constrictor muscle with its overlying mucosa. This flap is raised superiorly so that its base is at the level of the arch of C1. Typically, splitting the soft palate in the midline is necessary to provide better access to the nasopharynx during creation of the flap. The flap then is sutured to the nasal surface of the palate by incorporating it into the split repair.

Alternatively, the flap can be inset into the palate by performing a fish-mouth incision on its nasal surface. Raising a longer flap than necessary is advantageous to accommodate any future flap contracture. Red rubber nasal trumpets (4 French) are placed through the resulting lateral ports to alleviate any immediate postoperative obstructive breathing patterns.

One large series of 500 patients reported normalization or resolution of hypernasality in 90% of patients. Failure to improve is related to inadequate flap width either by design or due to contracture. Conversely, a flap that is too wide narrows the lateral ports and produces hyponasal speech. Postoperative airway obstruction is most likely to occur within the first 24 hours and in one series resolved within 2 days in more than 90% of patients.

The drawback to this surgery is the potential for prolonged postoperative obstructive sleep apnea development in up to 50% of patients. Care must be taken in the pediatric population to ensure adequacy of nasal respiration following paryngeal flap surgery. In many cases, this includes hypervigilance for obstructive sleep apnea both before and after surgery. Surgeons should definitely contemplate removal of large tonsils and adenoids prior to pharyngeal flap surgery.

Sphincter pharyngoplasty

Sphincter pharyngoplasty is advantageous when coronal or circular closure is present and lateral pharyngeal wall motion is deficient. The goal is to develop a more functional sphincter by improving the dynamics and bulk of the velopharyngeal tissues and by tightening and reducing the size of the velopharyngeal opening. [44, 45, 46, 47, 48]

Hynes was the first to describe pharyngoplasty in 1950 as the elevation of two superiorly based flaps comprising the right and left salpingopharyngeus muscles and overlying mucosa. [49] The flaps were rotated 90° and sutured to the mucosal edges of a transverse incision made across the nasopharynx just below the level of the tori tubarii.

In 1968, Orticochea described a modification of the pharyngoplasty procedure using two superiorly based flaps comprising the posterior tonsillar pillars with the underlying palatopharyngeus muscles. [50, 51] A small inferiorly based posterior pharyngeal wall flap then was elevated, and the two lateral flaps were rotated 90° and inserted onto the posterior flap.

Jackson further modified this method by sewing the lateral flaps onto a superiorly based posterior pharyngeal wall flap, allowing higher placement of the lateral wall flaps.

Theoretically, the sphincter becomes dynamic. However, one study featured selective electromyographic evaluation of the muscular pharyngeal sphincter during speech and revealed no intrinsic muscular activity. It is important to place these flaps high in the sphincter to reduce the need for revision surgery. [52] The sphincter pharyngoplasty has also been recommended for use in cases of stress-induced VPI, such as in wind-instrument players.

As noted, the need for adenoidectomy and possible tonsillectomy is determined preoperatively. (See Workup.) Adenoidectomy is performed several weeks (minimum, 6 weeks) preoperatively to allow the velopharyngeal sphincter to heal. If the tonsils are enlarged to a degree that may make raising the palatopharyngeal flaps difficult, they must be removed. Velar closure is then reassessed after adenoidectomy (and tonsillectomy) because the muscular dynamics may have changed.

Several studies have reported a success rate (ie, correction or significant reduction in hypernasality) from 78-100% with pharyngoplasty. The incidence of postoperative hyponasality is estimated to be 12-17%.

Posterior-wall augmentation

Posterior-wall augmentation is appropriate in the presence of a persistent gap in the central velopharyngeal port measuring at most 1-3 mm. It also is indicated when the patient can achieve touch closure that is not tight enough to prevent air escape with high oral pressure. Persistent postadenoidectomy VPI is also an appropriate indication for this procedure. Both autogenous tissue [53] and foreign implants have been used for this approach.

A superiorly based pharyngeal flap incorporating the superior constrictor is raised down to the prevertebral fascia. The superior extent of elevation is defined just above the point of maximal closure. It then is buckled onto itself and sutured in place. Initially good results can become less favorable as the flap can atrophy with time, and this procedure is recommended only for small gaps.

A wide variety of implantable materials have been used to augment the posterior wall. Problems with extrusion, migration, resorption, and infection have been reported. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has banned silicone because of a high extrusion rate. Teflon is not approved for use in the pharynx because of concerns over the risk of injection into large blood vessels. Autologous tissues such as fat or rolled dermis have been less problematic, but they tend to resorb with time.

Subsequent reports described the use of calcium hydroxyapatite injected into the posterior pharyngeal wall. [54] This technique has been demonstrated to have a reasonably high success rate with no migration or extrusion of the injected material. Polyethylene implants imbedded into the posterior pharynx have also demonstrated success in some adult patients. [55]

Although these procedures appear to be safe and relatively easy to perform, critical evaluation of procedures for posterior wall augmentation have not demonstrated significant improvements in speech following surgery. Autologous fat injections may be of some benefit in further augmentation after either sphincter pharyngoplasty or a pharyngeal flap procedure. The use of injectable collagen materials for pharyngeal augmentation has not been reported.

Predictors of postoperative outcome

Perceptual speech assessment is a key subjective tool used to diagnose VPI in children, determine disease severity, and measure improvement after treatment. Speech intelligibility is very important to patients with VPI and can have a large impact on quality of life. It is also important to develop standardized methods for use in research and improve overall management of patients with VPI.

One study validated a new disease-specific instrument, the Velopharyngeal Insufficiency Quality of Life (VPIQL) survey. This study identified that children with VPI and their parents perceive a reduced quality of life when compared with age-matched controls. [56] Another prospective cohort study implemented the Pediatric Voice Outcome Survey, an instrument used to assess general voice-related quality of life, and showed that parents perceived at least short-term improvements in fuctional outcomes and quality of life following surgery for VPI in their children. [57]

The greatest predictor for postoperative final speech outcomes from VPI surgery is the patient's preoperative condition. Children with syndromes such as VCF are more likely to have suboptimal outcomes after surgery than children anatomic, nonsyndromic causes of VPI. The type of surgical procedure used does not seem to be as important as the experience of the surgeon. A large, prospective, randomized study from Mexico found no difference in outcomes between sphincteroplasty and pharyngeal flaps, regardless of preoperative velopharyngeal sphincter characteristics. [58]

In summary, outcomes after VPI surgery are probably dependent on a multitude of factors, including severity of preoperative VPI, gap size, presence or absence of comorbidities or syndromes, and surgeon comfort.

There seems to be no long-term effect on growth after VPC over time. The ratio of cephalometric measurements of velar length to pharyngeal depth was similar in patients with repaired clefts and their normal control subjects. This ratio remained stable with growth from age 4 years through puberty. [59]

Postoperative Care

Immediate postoperative concerns deal mainly with upper-airway obstruction. Placement of nasal trumpets overnight, while the patient is still under the effects of anesthesia, is helpful. A 2-0 suture placed through the tongue tip and used to protrude the tongue can be helpful in temporary airway management in the postanesthesia recovery area.

Patients are admitted overnight primarily for airway management and intravenous (IV) hydration. Discharge home is on the first postoperative day as long as oral diet is tolerated and pain control by mouth is adequate.

Postoperative pain management is typically limited to narcotics, such as acetaminophen with either codeine or hydrocodone. Stronger narcotics, such as morphine or meperidine, may cause increased sedation, thereby worsening airway obstruction.

Once oral fluids are tolerated and any postoperative nausea has cleared, the patient resumes a diet of thick liquids and soft foods. With pharyngoplasty, a diet similar to that for tonsillectomy patients is used and may include most foods as tolerated. Patients undergoing a pharyngeal flap procedure follow dietary restrictions similar to those for patients undergoing palatoplasty. Typically, these patients are restricted to thick liquids or soft foods (eg, mashed potatoes) until the palatal incision has healed (usually 10-14 days).

Complications

Complications after VPI surgery include persistent VPI, flap dehiscence, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Concerns about long-term OSA development after pharyngeal flap surgery led some centers to abandon this procedure all together. A study of 222 consecutive pharyngeal flap operations reported a relatively low postoperative OSA incidence and concluded that when appropriately performed, pharyngeal flap surgery was well tolerated and effective for the treatment of VPI and that there was no reason to avoid applying it to children for fears of postoperative OSA. [60] In the case of severe persistent OSA after a superiorly based pharyngeal flap, division of the flap generally results in improvement in symptoms and some persistent speech benefit.

In a sphincter pharyngoplasty, more superiorly raised palatopharyngeal flaps lead to a greater degree of velopharyngeal obturation. If this is excessive, an obstructive pattern of breathing can develop. [61, 62] However, even if the obturation is not excessive, some patients still develop some mild temporary obstructive sleep patterns in the immediate postoperative period. For this reason, most surgeons place a nasal trumpet through the sphincter intraoperatively and remove it the next morning.

Long-term considerations include shrinkage of the flaps and nasopharyngeal scarring. Over time, the flaps may shrink, reducing the bulk of the repair and altering speech results. Patients with return of velopharyngeal escape over time may be a candidate for flap augmentation with fat injection. Nasopharyngeal stenosis may also result, especially if the dissection is carried up onto the soft palate. Resultant upper airway and nasal obstruction may require revision pharyngoplasty with tissue grafts.

After a pharyngeal flap procedure, failure to improve is related to inadequate flap width, whether through faulty design or as a result of contracture. [63, 60] Conversely, a flap that is too wide narrows the lateral ports and produces hyponasal speech. Postoperative airway obstruction is most likely to occur within the first 24 hours [64] ; in one series, it resolved within 2 days in more than 90% of patients.

After posterior-wall augmentation, problems with extrusion, migration, resorption, and infection have been reported.

Consultations

A team approach is important to success in the treatment of VPD. Close communication between the SLP and the surgeon is critical to determine the appropriate treatment modalities used. As speech motor patterns are set between age 8-12 years, timely consultation is crucial to good speech outcomes.

Role of speech and language pathologist

The surgeon, the SLP, and other health care providers work closely together to achieve the goal of optimal treatment for the patient. These practitioners collaborate in their reviews of the in-depth diagnostic assessment results and the individual patient’s medical history.

Consensus evaluation usually provides an appropriate course of management for affected individuals and may yield a differential diagnosis that leads to differential management. [65] Ideally, this means that care providers attempt to match the gap size, shape, and VPC pattern to the most appropriate intervention.

Surgeons, as well as lay people, are usually capable of recognizing speech “differences.” Perception of a speech difference does not require a sophisticated understanding of speech physiology, but determination of the causes, severity, and magnitude of that difference and formulation of a suitable treatment plan do require such an understanding.

SLPs are particularly adept at sorting out the components of a communication disorder and their respective weights, a process that frequently dictates whether a particular component receives surgical attention, not whether it receives attention at all. This sorting ability is a skill and a talent that surgeons and lay people rarely possess.

Relationship between speech and language pathologist and surgeon

Making the distinction between velopharyngeal valve dysfunction (structural defect) and speech dysfunction is critical. For example, consider the following analogy: If a newly licensed 16-year-old driver is involved in a motor vehicle accident, differentiating between a mechanical failure of the car and a failure of the just-learning driver to maintain control of the vehicle is important.

The investigator might logically ask: Was the driver taking mind-altering drugs? Was the accident the result of a mechanical problem with the car, or was it the fault of an inexperienced or misbehaving driver? The answers to these questions are basic to the investigational algorithm. They tell the investigator where to look next, while reminding him or her that more than one party might be at fault.

The same logic holds true for the evaluation and management of VPD. Is the velopharyngeal valve (the car) at fault, or is the speech disorder (the driver) at fault? The answer to this question tells the investigator what to do next and who should do it.

Examining the velopharyngeal valve should be quite straightforward. A simple mirror test at the bedside, with a definitive yes-or-no answer, can help determine if the patient can eliminate nasal escape. Treatment may involve fixing the velopharyngeal valve (which calls for a surgeon’s expertise) or teaching the patient (which calls for the expertise of an SLP).

The presence of hypernasality is much more difficult to evaluate. Using vocal, nonverbal testing can obviate such problems as phoneme-specific VPI. An astute SLP should be able to make the determination despite the confounding glottal stops, fistulae, and other factors.

The surgeon must emphasize to parents, patients, and other providers that surgical success can be anticipated with respect to nasal escape and hypernasality. The SLP must then assume the responsibility of helping patients achieve speech and language success, including articulation and other facets of verbal communication.

Long-Term Monitoring

The initial follow-up appointment is at 7-10 days, at which time the wound is examined for proper healing. A determination regarding resuming a regular diet also is made at this time. Snoring and upper airway obstruction, if present at this point, usually resolve over the next several weeks as edema decreases and flap shrinkage occurs.

At 6 weeks, healing is usually complete, and a speech and resonance reassessment is performed. Surgical correction of structural defects in the velopharyngeal port does not necessarily change function, and articulation problems may persist after surgery. On the basis of the postoperative speech and resonance evaluation findings, speech therapy may be resumed at this point as necessary.

-

Coronal closure.

-

Sagittal closure.

-

Circular closure.

-

Circular closure with Passavant's ridge.

-

Patient with severe articulation disorder and velocardiofacial syndrome. Little or no velar closure is noted on nasopharyngoscopy ("black hole"). Surgical treatment is with wide pharyngeal flap. Aberrant carotid arteries coursing through nasopharynx complicate surgical management.

-

Infant born with heart murmur, submucous cleft palate, and lower lip asymmetry. Clinical findings are consistent with velocardiofacial syndrome.

-

Child with velocardiofacial syndrome. Characteristic clinical findings included unilateral lower lip palsy, small bulbous nose, wide palpebral fissures, and small external ear canals. Patient's speech has hypernasal resonance.

-

Pharyngeal closure patterns: (A) coronal, (B) sagittal, (C) circular, and (D) circular with Passavant ridge.

-

Coronal closure noted. Primary movement is palate contacting posterior pharyngeal wall, with minimal or no movement of lateral pharyngeal walls. Notice air escape along lateral margins as palate contacts adenoid pad.

-

Sagittal closure demonstrated. Soft palate moves little, with most of the closure achieved by movement of lateral pharyngeal walls. Notice notching of soft palate consistent with submucous cleft palate.

-

Example of circular closure with contributions from palate and lateral pharyngeal walls. Patient underwent recent adenoidectomy as evidenced by nasopharyngeal eschar.

-

Circular closure with Passavant ridge demonstrated. Note elevation of ridge on posterior pharyngeal wall contributing to closure.

-

Case study of patient status post cleft palate repair. Child presents with hypernasal speech, especially with /s/. No history of nasopharyngeal reflux. Intraoral examination demonstrates repair to be intact except for posterior most portion (bifid uvula is noted). Nasopharyngoscopy demonstrates notching of soft palate (arrow) and enlarged adenoid pad (asterisk).

-

Velar closure noted as patient pronounces /s/. Circular closure pattern is noted with central defect and air escape. Palate closure is noted with swallow in middle portion of frame.

-

Palate closure noted against adenoid pad as the patient speaks /p/. Phoneme-specific velopharyngeal dysfunction is diagnosed, and speech therapy is recommended to improve articulation. Adenoidectomy in this patient would most likely result in structural velopharyngeal insufficiency.

-

Palatal lift. Hard and soft palatal components are shown.

-

Palatal lift in situ.

-

Preoperative nasoendoscopic view of velopharynx, showing nasal septum (1), lateral nasoparyngeal wall (2, 4), and velum (3).