Etruscan sculpture

Etruscan sculpture was one of the most important artistic expressions of the Etruscan people, who inhabited the regions of Northern Italy and Central Italy between about the 9th century BC and the 1st century BC. Etruscan art was largely a derivation of Greek art, although developed with many characteristics of its own.[1] Given the almost total lack of Etruscan written documents, a problem compounded by the paucity of information on their language—still largely undeciphered—it is in their art that the keys to the reconstruction of their history are to be found, although Greek and Roman chronicles are also of great help. Like its culture in general, Etruscan sculpture has many obscure aspects for scholars, being the subject of controversy and forcing them to propose their interpretations always tentatively, but the consensus is that it was part of the most important and original legacy of Italian art and even contributed significantly to the initial formation of the artistic traditions of ancient Rome.[2][3] The view of Etruscan sculpture as a homogeneous whole is erroneous, there being important variations, both regional and temporal.[4]

Historical context[edit]

The origin of the Etruscans has been the subject of controversy since antiquity. Herodotus believed that they were the descendants of populations coming from Anatolia before 800 BC, who displaced the previous inhabitants,[5] although Dionysius of Halicarnassus had them as autochthonous. Modern research has not reached a consensus either and experts ended up considering this issue unsolvable, going on to study, how society was organized, rather than where they came from.[6] What is known with certainty is that by the middle of the 7th century BC their main cities had already been founded, beginning immediately a period of territorial expansion that ended up dominating a large region more or less in the center of the Italic peninsula, ranging from Veneto and Lombardy to Latium and Campania, what has been called Etruria.[7] However, in the following centuries their conquests were threatened and several Italian peoples managed to have their advances remitted. Finally, their last strongholds were taken by the Romans, who absorbed their culture and caused their dissolution. At their peak, the Etruscans were the most powerful people in pre-Roman Italy and established a thriving civilisation with a large agricultural production, a powerful fleet, a flourishing trade covering much of the Mediterranean Sea and a unique culture, where art played a great role, having a major influence on the initial formation of the art of Ancient Rome.[3][8]

Their presence in Italy is assumed from the 9th century BC, but inscriptions on monuments and objects, which provide greater certainty in their dating, only appear around 700 BC. Although they shared a common culture, the Etruscans did not form a coherent political unit and their social organisation was similar to the Greek polis system, they even fought each other as well. There are no surviving literary Etruscan texts, their history can be recovered directly from archaeological evidence, but much of what is known has been recounted by the Greeks and Romans. Titus Livy speaks of a society of "Etruscan people" made up of "brothers-in-law" (consanguineous), "sodales" (brothers in arms) and "clients" (people who offered their services and expected to receive protection from their patrons.)[9]

Greece and Etruria[edit]

They maintained contact with Greece, possibly from their origins, a contact that intensified when the Greeks founded their first colonies in the south of the Italic peninsula, around 775-750 BC. They adopted an alphabet similar to the Greek alphabet and, also part of their mythology[5] and imported Greek utensils in large quantities, especially ceramics. These objects found in Etruscan territory have been one of the sources for determining the chronology of their history.[1][8] The oldest inscriptions in the Etruscan language date back to the 7th century BC and the first signs are painted on pottery, always related to the Greek alphabet but adapted to the local language. Writing has also been found on tablets inside princely grave goods, which was a sign of social distinction.[10] In fact, the Greek influence has become so important that the nomenclature of Etruscan art history mirrors that used to describe the corresponding periods of Greek art:[8]

- Vilanovan Period or geometric: 9th-8th BC.

- Orientalizing Period: 7th century BC.

- Archaic Period: 6th to mid-5th century BC.

- Classical Period: mid-5th to mid-4th century BC.

- Hellenistic Period: 3rd-1st century BC.

Even with the massive assimilation of foreign culture it is significant that both the Greeks and later the Romans considered the Etruscans a perfectly individualised people. The study of Etruscan culture began in the Renaissance and deepened from the 19th century, but older historians often condemned their sculpture, seeing it as a mere imitation, without creativity, of Greek art. This position has been changing in recent years and today it is considered an original phenomenon. In any case, the distinction between Greek sculptures in Etruria and Etruscan sculptures proper is often still very difficult for modern critics. The influences Phoenician art, Roman art, Egyptian art and Eastern art, together with the loss of much of their most relevant sculptural production, make the problem even more complicated.[1][11] However, the examination of Etruscan sculpture, in comparison with its neighbours, especially the Greeks, can lead to biased estimates of value and significance that prevent appreciating it for its intrinsic and typical values, since historically Greek sculpture, especially of the classical period, was often considered as the ideal model of Western sculpture; a view that still resonates in studies and popular vision. The completion of several archaeological excavations in recent years on sites found intact and the restoration of capital works that had been disfigured by interventions in the 19th century, have provided a great deal of additional authentic information for a greater understanding of the dark corners of this subject.[2][11]

Private sculpture[edit]

One of the distinctive features of Etruscan sculpture is that it served, primarily, for private decoration and religion.[12] In their zenith period, the Etruscans developed a wealthy and cultivated elite, lovers of art and luxury, but unlike other peoples of antiquity, they seem to have had no interest in recording through art their own history, extolling the virtues of the citizens. Neither did they create great works of worship for the gods nor did they wish to adorn their cities with great civil monuments to proclaim the glory of their civilization. Therefore, the figure of a creative artist or stylistic schools recognized for their individual genius did not emerge either. Their art is anonymous, collective, eclectic and non-competitive. However, the name of an Etruscan sculptor (Vulca) who worked in Rome and became famous there is known.[13] Thus, sculpture was essentially utilitarian, both religious and decorative or private. Their deep belief in life after death made them develop a complex system of funerary practices, whose aim was mainly to provide comfort to the dead in their sepulchral abode and to please the gods by filling it with objects that were intended to facilitate their afterlife. From the Archaic period onwards, the design of the tombs was carried out as if they were real houses for the dead; a custom that continued until their immersion in Roman culture. Their characteristics varied according to the period, the region and the social class of the deceased and in certain phases, the tombs of the most important people became extraordinarily rich.[2][14]

Religious sculpture[edit]

Religion also determined the preference for certain types of sculpture present in tombs, such as votives and statuettes of the gods, beyond the sculpted figures of the dead in funerary urns and sarcophagi. Statuary linked to funerary contexts is by far the most abundant Etruscan production.[2][15] Other typologies are also important such as the embracing couple and various statuettes, amulets and reliefs showing images of a strong sexual character, used in a wide variety of ritual conjuration practices. Scenes of human sacrifice also appeared frequently, often in striking realistic detail with the episode of the sacrifice of Iphigenia being especially common. The images possibly did not reflect real sacrifices, but substituted them symbolically. Another recurring theme is the figuration of various local and Greek myths, focusing mostly on violent battle scenes. But while the Greeks created many images of gods and deified even abstract virtues, the Etruscans approached them much less concretely, with several images of which it is not even known if they were any local divinity.[14][16]

Decorative sculpture[edit]

As for nudity in sculpture, the Etruscans had very different opinions from the Greeks. While the latter widely favoured it, the former avoided it, rarely showing nudity, but innovated the type of the nursing mother with exposed breast, unprecedented in Greek art, a typology that with the advent of Christianity would be a direct ancestor of a variation of the fertile type of the Virgin, the Virgo lactans.[17] With respect to their stylistic canons, according to Cunningham and Reich, the Etruscans were not like the Greeks, concerned with deep reflections on the associations between art and ethics or the understanding of how the body functions in an artistic representation and their attention was directed more to the immediate effects of the figures.[18] Proof of this is the existence of countless distorted, schematic or disproportionate figures, often with a rudimentary finish, approaching the character of caricature, highlighting individual features without any idealism. For the decorative groups on the façades of temples and on some private buildings, their composition was not a logical complement to the form of the building, but a free decorative addition, regardless of the architectural coherence. These groups are the most typical and original genre of monumental Etruscan sculpture.[2]

Periods[edit]

Villanova[edit]

The period of Villanova culture, sometimes called geometric, was the prelude to the formation of the Etruscan civilization. Its name is the same as that of an important archaeological site, that of Villanova, discovered in 1853 by Giovanni Gozzadini, near Bologna, characterized by the funerary rite of burial and by the biconical cinerary vase.[19] The period was characterised by the expansion and refinement of metallurgy and by an art that often employed simple geometric motifs arranged in complex patterns, inherited from earlier cultures—local and Greek—and which would remain in Etruscan art until historic times. The earlier local tradition—called "proto-Vilanovanian" culture—seems to have influenced the custom of adding small sculptural elements on funerary vessels and urns, while the Greek element is manifested in the creation of tiny animal figures in bronze, which basically imitate the designs found on the vessels.[20] Vulci was probably the first center to have a typically Etruscan artistic tradition, manifested in forms of vessels and cauldrons with small groups of figurines of men and animals on their lids. These were the first human representations in Italian art only attributed with some certainty to mythological characters from the end of the period.[2][4]

The artistic production of Villanova seems to have been abundant, but there are few sculptural remains. The objects recovered by archaeologists have been found in funerary contexts inside the tombs where urns containing various objects were deposited.[2] They are of small dimensions and are mostly utilitarian bronze objects, such as harnesses for horses, helmets, arrowheads and spearheads, pitchers, bracelets, necklaces, as well as cauldrons and pans and other utensils of unknown utility, along with ceramic vessels of all kinds: pots, jars and plates.[21] Many of these objects are clearly of Oriental origin, indicating active trade with distant regions.[22] Etruscan princes imitated the Neo-Assyrian rulers and with the purchase of luxury goods asserted their power before their community.[23] The great demand that was produced, made necessary the creation of local workshops in which the iconographies of the Eastern Greek world were developed, anthropomorphic figurines were produced, highly stylised and schematic but of great vivacity.[24]

Orientalizing[edit]

The number of pieces of oriental typology found in the tombs of the end of the 8th century B.C. is so great that the whole period was called Orientalizing. It is then that trade with the Greeks and Phoenicians intensified, becoming their main trading partners. This increased circulation of goods from a wide variety of places was due to the need to satisfy the desires of an elite that had become organized, enriched and ennobled.[25] The main cities of the time, Vulci, Tarquinia, Cerveteri and Veii, became the main commercial centers, and the greatest number of sculptural remains have been found, again, in subway tombs. During this period, the tombs became larger and more complex, with several chambers, corridors and a large vaulted roof at the top, formed with concentric rings of gradually advancing blocks, sometimes with a central pilaster helping to support the roof.[26] Burials were often luxurious, including a profusion of both decorative and sacred objects, the warrior princes, invested in buying sumptuary goods in the likeness of oriental pomps and typologies.[27]

Decorative motifs such as palm leaves, lotus and lion became frequent and good examples are the bracelets and pendants with ivory lion figures found at Tivoli, a silver plaque in relief depicting the "Lady of the wild beasts", of uncertain origin, and the large bronze shields used to hang on tombs, especially those of Cerveteri, decorated with reliefs in a style reminiscent of the geometric patterns of the culture of Villanova, but including other oriental elements. In ceramics, the novelty was the imitation of forms hitherto reserved for bronze, giving them a new boldness in the modeling of full-bodied figures and in sculptural accessories such as vases. Of particular interest are the small aryballos in the shape of animals used to store perfumes, together with other vessels with complex decorations—the buccheros—which can also be catalogued as sculptures, and the canopic jars with lids covered with anthropomorphic figures that could have large dimensions and be enthroned. Noteworthy in this phase is the development of the art of jewelry, richly ornamented, of which there are examples comparable to miniature sculptures.[1][4][22]

Greek myths already appeared frequently in Orientalist representations but it is possible that they were interpreted according to local religious traditions. It was during this period that the first Etruscan cult statues emerged, a religious typology different from the votive statuettes already seen in the previous phase. Some are easily identifiable from their Greek models, but others are local adaptations, requiring scholarly interpretation to identify. As an example of this are statues of a god throwing a thunderbolt, which could be Zeus, but young and beardless, further complicated by knowledge of at least nine Etruscan gods with the lightning attribute, as related by Pliny the Elder.[24][28] By the end of the period, his artistic production had already succeeded in formulating an aesthetic that consciously surpassed the mere imitation of foreign models and his skill with precious metals and bronze, became known beyond his borders.[4]

-

Rabbit-shaped aryballos, terracotta.

-

Bucchero type vase, made of terracotta.

-

Cauldron with lion heads, bronze.

Archaic[edit]

The importation of the archaic style from Greece was natural, taking into account the continuity of the strong commercial and cultural ties that united both peoples and favoured by the fact that around 548-547 BC the Persians conquered Ionia, causing the flight of many Greeks to Italy. Many of them were artists who brought a new aesthetic in the construction of the human figure with stylised or large, more naturalistic lines. The Greek archaic types of production were developed following essentially idealistic rules and set definite models that illustrated plastically the ethical and moral concepts, not finding an exact imitation among the Etruscans, since they realized the shape of the human body with a much more descriptive profile and, in fact, making images almost like portraits, when among the Greeks all the personal idiosyncrasy had been abolished from the images. Another difference is that the male figure, although it was very similar to that of the Greek kouros used to dress and the patterns of his clothes were related to the clothes of the female kore. In addition, they had a special taste for ornamentation, introduced many new decorative details and used a greater number of characters in group scenes than their Greek models. There were also differences in the material used, which, in general, was terracotta, preferring coroplast which is where they made their most perfect works. They also employed stone although never with the originality and freshness they achieved with clay and ignored marble.[29] One of the best known examples of free-standing or isolated statue of this phase is the cult sculpture of Apollo of Veii, currently in the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia.[1]

During this period important changes were made in sculpture also due to changes in the field of architecture and religion. The fusion of Etruscan and Greek mythologies brought about a rapprochement in the forms of worship. The form of the Etruscan temple, which previously differed little from a common house, was modified and enlarged, becoming similar to the Greek temple. Again, the assimilation was not literal, using alternative materials for its construction, showing different divisions in the spaces of the building, in its distribution and design of columns and with the use of many decorative details in terracotta polychrome, such as friezes, acroterion, antefixs and plaques with narrative scenes or with various ornamental motifs. The decoration of the main temples—smaller than the Greek ones but more decorated—was crowned with a large sculptural group in high relief on the pediment, also in terracotta, a typology that was consolidated in the mid-6th century BC as one of the most typical and original genres of Etruscan monumental sculpture. Great examples of this new trend are the group of Temple A at Pyrgi and another at Veii.[30] Similar changes occurred in the construction of the tombs, making them more complex and larger, with various rooms decorated according to their functions as if they were houses and decorated with sculptural elements, such as pedestales, columns and capitales, and reliefs of various types.[1][2]

From this period onwards, the representation of the "banquet" scene is frequent, in which, unlike the Greek tradition, the women are represented lying next to their husbands. This is how they are shown in the funerary trousseaus and in some urns of Chiusi both in the painting of their walls and in the reliefs of the urns.[31] Thus began the development of a new type of burial urn, with the dimensions of a sarcophagus for bodies that were not cremated, but buried. It consisted of a box decorated with reliefs on the sides and covered with a lid on which the dead were represented in a reclining position, as if they were at a banquet.[32] Sometimes they represented couples, such as the famous Sarcophagus of the spouses of the National Etruscan Museum. The figures of the deceased, however, were not portraits, but generic types. It is possible that this genre was inspired by the Carthaginian burial tradition, merged with the Egyptian model with a mummy-shaped lid and the oriental one in the form of a box. The Etruscan sarcophagus model would be used much later in Rome, spreading over a large area of the Mediterranean.[1][2]

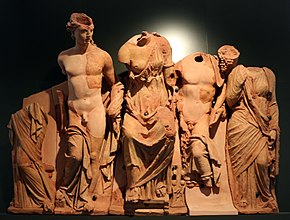

-

Group with mythological scene, terracotta, Pyrgi.

-

Apollo of Veii, terracotta, Veii.

-

Sarcophagus of the spouses, terracotta, Caere.

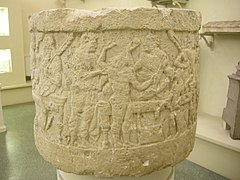

-

Banquet scene, limestone, Chiusi.

-

Mythological scene, embossed silver, San Marino Castle.

-

Detail of Monteleone chariot, Brufa.

-

Votive statue, bronze, Chiusi.

-

Tripod, bronze, Vulci.

Classic[edit]

The archaic style remained predominant in ancient Etruria, while in Greece, the classical canon prevailed in the 5th to 4th centuries BC. In fact, it was practically ignored among the Etruscans. Massimo Pallottino justifies this difference by saying that classical Greek culture was at that time, for various reasons, more centered in Athens and the Peloponnese and had somehow blocked the influence of its radiation to neighboring regions.[14] For her part, Nancy Grummond describes the phase as "neutral" which gave rise to only a few important works, the Mars of Todi, which is close to the canon of Polykleitos, the famous Chimera of Arezzo which has a classical influence but still retains archaic traces, the Bust of Brutus (sometimes considered a Roman work) and architectural decorations in Orvieto and Falerii. Although rare, these examples show great mastery in the construction of the form and technique of casting and are considered masterpieces. After the fall of Veii in 396 BC under the Romans, the most active production centers came to be in Chiusi, Falerii and Bolsena, seat of one of the most important Etruscan sanctuaries.[2][24]

Classical Greek sculpture continued to show great idealistic concern as in the archaic phase, but now with a remarkable ability to imitate the anatomy of real bodies showing a combination between the ideal and the natural in human figures, giving them a timeless, archetypal and exalted character, even when it came to gods. The Etruscans also reaffirmed their originality, preferring a level closer to the natural and ornamental. Their deviation from the foreign canon cannot be explained by an alleged misunderstanding of the model, since the Etruscan elite was far from being ignorant and the artists had demonstrated high technical ability, but because they had different goals in art. Understanding these differences is particularly relevant to the study of the classical Etruscan period because of the large number of mythological figures that have survived.[2][24][33]

In the case of the sarcophagus, there is a slightly greater concern to describe more closely the physiognomy of the dead, although they can hardly be considered true portraits. The figures are presented with more variety of forms, appearing even as sleeping persons.[1] Parallel proliferate votive statuettes of gods and votive offerings in the form of heads, which have been preserved in large numbers, but have not yet been sufficiently studied.[2]

-

Bust of Brutus, bronze.

-

The Chimera of Arezzo, bronze.

-

Winged-Horses of Tarquinia, terracotta.

-

Apollo statuette, bronze.

Hellenistic[edit]

The Hellenistic phase is one of the most difficult to describe. At that time the Etruscan empire was in decline, threatened by its neighbors, especially the Romans, who were conquering one by one its cities. In the clash of the two cultures, a process of fusion began. Their social structures changed, emphasizing military government and the formation of a new aristocracy with the assimilation of the enriched plebeians. Religion and funerary customs are increasingly simple, as tombs decorated with the luxury of previous phases were not made, nor with so many objects or accessories, suggesting that the interests of society were turning more to the present life than to the afterlife, all the more so because pessimistic visions regarding the future of their people were beginning to predominate.[24] Instead, contact was resumed with Greece, which was already working under Hellenistic eclecticism.[14]

Sarcophagi and urns still continued to be highly decorated pieces, but the sculptures of the dead became more schematic and generic. Although the formal repertoire continues to be varied, around the 2nd century BC the models were already established and the demand was such that it led to their mass production, from the same mold—in terracotta—or from the same model—in stone—with a strong decrease in individualized pieces. The same happened with the pieces of heads and votive statuettes, their quality also tended to decline, possibly caused by the intensive production of second or third generation molds and the renunciation of manual work after modeling. The urns were produced mainly in Chiusi, Volterra and Perugia, while the sarcophagi came from Viterbo and Tarquinia. The most important tombs in this period are found in the Tarquinia region, Tuscany, Perugia and Sorano.[34][35]

The architectural groups tend to be more populated with figures, arranged in sections that alternated great movement and violence with others of a more peaceful atmosphere and using eclectic resources from various sources, including the archaic. Important examples of this phase are the groups of the pediment of Talamone of Luni or The Orator, a statue in bronze exempt.[36] By the 1st century BC the quality of the works in general became very poor and all original Etruscan production had already succumbed to Roman influence, coming to an end.[35] The Etruscans obtained Roman citizenship in the early 1st century and their territory was named Regio VII Etruria, one of the eleven comprised in the Augustan reform.[37]

-

Female head, terracotta, Vulci

-

Menelaus and Meriones lifting Patroclus’ corpse on a cart while Odysseus looks on, alabaster, Volterra.

-

Sarcophagus of Larthia Seianthi, terracotta with traces of polychrome, Chiusi.

-

Head of deity, bronze.

-

Minerva between Hercules and Lolaus, in a mirror, bronze inlaid with gold and silver.

-

Polychrome terracotta tomb cover.

-

Antefix in the form of the head of Attis, terracotta, Fiesole.

-

Lid of a funerary urn, terracotta, Volterra.

Materials and techniques[edit]

Terracotta[edit]

The vast majority of sculptural remains, both large—architectural statuary and sarcophagi—and smaller pieces, were made in terracotta, whose ease of handling perfectly served the purposes of sculptors and patrons and the great demand for funerary and decorative works. In addition, this allowed the creation of serial pieces through molds, a technique learned from the Greeks. A clay prototype was modeled by hand, from which several models were made, and with these the prototype could be replicated numerous times until the mold wore out and was replaced again. The piece was removed from the mold, while still wet so that details could still be added or manufacturing imperfections rectified, giving each piece a unique character. In turn, the molded parts could also serve as a new prototype for a second generation of molds and copies. On the one hand this made possible the mass production of similar pieces at low cost to meet the growing demand but as the molds wore out their quality declined, which proved fatal to Etruscan art, especially in its final phase, when the finish had been greatly reduced, with no additions or corrections after molding. However, the quality of the final finish of the works was very varied existing cases of important statuary with a surprisingly rustic finish, even in stages before mass production as the great building of Murlo, whose cornice was decorated with at least thirteen life-size acroterion, as well as with terracotta slabs with representations of various scenes, but with a very rudimentary technique.[38] Other examples, however, are of great refinement, among which is the pediment of the temple of Portonaccio in Veii, with a mythological scene, and another set of exception is the Pediment of Talamone. More general, however, was the use of simple plaques and friezes with various scenes and minor details such as antefixs, acroteria and medallions with human, animal, plant and abstract motifs.[2][35]

Other materials[edit]

Stone was never widely used in Etruscan sculpture. There are few examples of sculptures in soft limestone, alabaster or toba; marble is even rarer. Its dimensions are modest and its technique rather primitive. The details were often roughly worked, but the imperfections were hidden by the practice of painting on the surface. In a workshop at Chiusi mourners and sphinxes were sculpted in local stone, while at Vulci sculptures of fantastic beings derived from Greek mythology were made.[39] Only in the Hellenistic period are more examples of stone sculpture found, especially for sarcophagi, but the technique does not appear to have evolved significantly.[40]

Ivory, wood and bronze were also exceptional materials for large statues, although it may be that many important pieces may have been lost. For elaborating small pieces, bronze was a privileged material with which they reached a high degree of technical knowledge and formal complexity. They mastered several techniques, such as lost wax, engraving or lamination. They were able to add to bronze other metals such as gold, copper or silver inlays and their production had a large market among several of their neighboring peoples, especially the Romans, this being a technique praised by Horace.[2][14][41] Among the pieces made in amber from the 5th century BC is the fibula from the Morgan Amber kept at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[42]

The sculptural heritage[edit]

The main sculptural legacy by the Etruscans developed in Rome, where Roman sculptures dated to the 6th century BC are clearly Etruscan in style; an influence that continued into the Hellenistic period and possibly beyond, there are even signs of it as far back as the time of Augustus.[43]

15th - 16th centuries[edit]

The Etruscan tradition fell into oblivion until the 15th century when it began to be rescued from the work of the monk Annio da Viterbo, cabalist and orientalist, who published a book where he speculated on a possible common origin of the Hebrew and Etruscan languages, after having carried out several excavations in tombs, discovered sarcophagi and tried to decipher their language.[citation needed] This attention grew until in 1553 the famous Chimera was discovered in Arezzo, then moved to Florence where it caused a great sensation among artists and scholars. It was exhibited in the Palazzo Vecchio as a marvel of antiquity. Along with other statues found with it, it passed into the private collection of Cosimo I de Medici. At a time when Rome had supplanted Florence in cultural and political prestige, the discovery was invested with a nationalistic character, becoming a symbol of lineage of prestige and specific Tuscan identity.[44]

17th - 18th centuries[edit]

In the 17th century the Scottish scholar Sir Thomas Dempster made a significant contribution to knowledge of the Etruscans with the seven-volume work entitled De Etruria Regali, a compilation of ancient sources accompanied by ninety-three engravings showing their monuments. His work, however, remained unpublished until 1723, when Filippo Buonarroti published it along with commentaries on his own work, this work is considered a milestone in modern Etruscan history. Three years later the Accademia Etrusca was created in Cortona, which in a short time was adding various specialized studies. In 1743, Antonio Gori brought out his Museum Etruscum, with hundreds of illustrations, and in 1761, Giambattista Piranesi published a volume on Roman architecture and engineering, where he advanced several theories about Etruscan involvement in Roman art that were later confirmed.[45]

These pioneering works naturally contained many errors, inaccuracies and false attributions, but they contributed to a first more scientific delimitation of the field of study and also to the gestation of neoclassicism, whose intense interest triggered a collecting fever among European political and intellectual elites. With Winckelmann, one of the most influential neoclassical theorists, studies reached a higher level, writing extensively on Etruscan art, including sculpture, distinguishing clearly between its style and Greek, he also recognized its internal variations, praised the skill of its artists and considered it "a noble tradition".[28][45] In the 19th century, Hegel, although more concerned with the idealistic aspects of ancient art, did not fail to appreciate Etruscan art, recognizing that it demonstrated an interesting balance between idealism and naturalism, representing very well the practical spirit of the Romans.[46] The Etruscan sculpture pieces were a revelation to Romantic Ruskin, helping him to understand Western art history.[47] Friedrich Nietzsche, however, despised them.[33] Frobenius drew analogies steeped in fantastic romanticism between the Etruscan art of his sculpture and the pre-Columbian peoples, in vogue at the time, linked to theories about Atlantis.[48]

19th century[edit]

Even in the 19th century Etruscan sculpture gained an important forum for discussion when the Istituto di Correspondenza Archaeologica was created in 1829 to promote international cooperation in the study of Italian archaeology, publishing many articles and carrying out excavations in several necropolises. However, the increasing availability of significant finds caused the destruction of numerous archaeological sites by wreck hunters, disasters denounced by the British consul in Italy, George Dennis in his book The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria of 1848, which immediately became a best seller and whose third edition (1883) remains a good introduction to the subject. Another important publication was Antica Etruria Marittima (1846–51) by Luigi Canina, with the introduction of a revolutionary topographical methodology. But perhaps more important was the contribution of Alois Riegl, who, although not particularly focused on Etruscan art, definitively established the validity of neoclassical artistic expressions, at a time when the Greek legacy was considered a model. Meanwhile, some sectors involved in the process of Italian unification came to take the Etruscans as the most legitimate source of the origin of the Italian people, tinging the cultural debate with tendentious political and patriotic color.[14][33][45]

20th century[edit]

In the early 20th century Etruscan sculpture may have influenced Picasso's classical prints. At the same time, Christian Zervos, while cataloguing the artist's works, commissioned a study of Etruscan art by the archaeologist Hans Muhlestein, which was published in the article Histoireet esprit et contemporain, where he recommended to modern artists the study of ancient art as an antidote to the then prevalent idea that the world was governed by a purely mechanical force.[49]

Another important sculptor, Marino Marini, declared that his discovery of Etruscan art was "an extraordinary event" and his enthusiasm was only part of a revival wave of great importance for the evolution of Italian modern art during fascism, strengthening at the same time the fascist myth of the supremacy of the Italian people and of Latin traditions. Several Italian intellectuals of the time reaffirmed the qualities of the Etruscan style and praised artists for having revalued it before archaeologists.[50] In many ways, Etruscan culture was the subject of renewed fascination in early 20th-century Europe, including among its admirers Aldous Huxley and D. H. Lawrence.[51][52] This reputation, in parallel favoured the appearance of an increasing number of fake works on the market. The cases that had the greatest repercussions were the works created by the family of Pio Riccardi and Alceo Dossena, so well executed that they were acquired by important museums and remained on public display as authentic for several years until the fraud was discovered.[53]

Several institutions in Europe and United States have dedicated in recent decades, significant funds for theoretical research projects, excavations and formation of collections of Etruscan objects and art, contributing to a better understanding of a subject that is largely hidden by unknowns. Particularly important are the collections of the National Etruscan Museum at Villa Giulia, the Louvre, the National Archaeological Museum of Florence and the Metropolitan Museum of New York. Many of the most important collections have been established between the 19th and early 20th centuries, when many sites were excavated by adventurers without judgment to supply the black market in antiquities and, even when excavated by experts, archaeological procedures had not been standardized and were just beginning to conform to the methodologies of modern science. This has led to the irretrievable loss of information about stratigraphy, origin, background and other issues vital to contemporary study. A study that from the beginning has been hampered by the lack of written Etruscan documents, which prevents us from knowing what they thought, about their art in their own words.[33][45][54][55]

The Etruscans have recently been a source of inspiration for many writers of fiction or pseudo-historical literature, taking advantage of the aura of mystery that still hangs over them in popular culture and, on the other hand, narratives have been written that sell well and attract the attention of a large audience to Etruscan culture, although, in Ross's words, "they perpetuate stereotypes and do a disservice to true knowledge". Other authors suggest that the Etruscan legacy in central Italy is alive in popular superstitions and religious symbols, in agricultural practices, in certain forms of public celebration, and in the decorative projects of buildings and house interiors, especially in relief carving techniques.[51][54]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (2005). A world history of art. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 9781856694513.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Briguet, Marie-Françoise; Bonfante, Larissa (1986). Etruscan life and afterlife: a handbook of Etruscan studies. Wayne State University Press. pp. 92–173. ISBN 0814318134.

- ^ a b Hall, John Franklin (1996). Etruscan Italy: Etruscan influences on the civilizations of Italy from antiquity to the modern era. Indiana University Press. pp. 3–16. ISBN 0842523340.

- ^ a b c d Cristofani, Mauro (2000). Etruschi: una nuova immagine (in Italian). Giunti Editore. pp. 170–186. ISBN 9788809017924.

- ^ a b Barral i Altet (1986, p. 228)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, p. 6)

- ^ Staccioli (1993, p. 5)

- ^ a b c Ancient Italic people: The Etruscans. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, p. 100)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, p. 32)

- ^ a b Arafat, Karim; Morgan, Catherine (1994) Athens, Etruria and Heunenburg: Mutual misconceptions in the study of Greek-barbarian relations. Classical Greece: Ancient histories and modern archaeologies. New directions in archaeology series. Cambridge University Press, pp. 108-134

- ^ Staccioli (1993, p. 24)

- ^ Staccioli (1993, p. 31)

- ^ a b c d e f Pallottino, Massimo (1984). Etruscologia: Storia, filosofia e religione. Hoepl, pp. 365-375 (in Italian)

- ^ Grummond, Nancy (2004). For the Mother and for the Daughter: Some thoughts on dedications from Etruria and Praeneste. pp. 351–370. ISBN 9780876615331.

- ^ Bonfante, Larissa; Swaddling, Judith (2006). Etruscan myths: The legendary past. University of Texas Press, pp. 50-60

- ^ Bonfante, Larissa (1997). Nursing Mothers in Classical Art. In Koloski-Ostrow, Ann Olga & Lyons, Claire L. Naked truths: women, sexuality, and gender in classical art and archaeology. Routledge. pp. 174-196

- ^ Cunningham, Lawrence S.; Reich, John J. (2005). Culture and values: a survey of the humanities. Volume 1 of Culture & Values Series. Cengage Learning. pp. 129-130

- ^ Staccioli (1993, p. 52)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, pp. 6–7)

- ^ Bartoloni (2008, p. 39)

- ^ a b Brown, A.C. (1980). Ancient Italy before the Romans. University of Oxford, Ashmolean Museum. pp. 26-31

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, p. 12)

- ^ a b c d e Grummond, Nancy Thomson de (2006). Etruscan myth, sacred history, and legend. University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology. pp. 2-10.

- ^ Bartoloni (2008, p. 43)

- ^ Staccioli (1993, p. 20)

- ^ Bartoloni (2008, p. 66)

- ^ a b Winckelmann, Johann Joachim (2005). Essay on the philosophy and history of art. Continuum International Publishing Group. Volume 2. pp. 229-256

- ^ Staccioli (1993, p. 28)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, pp. 40–41)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, pp. 46–47)

- ^ Staccioli (1993, p. 29)

- ^ a b c d Barker, Graeme; Rasmussen, Tom (2000). The Etruscans. The Peoples of Europe series. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 3-9

- ^ Turfa, Jean MacIntosh (2005). Catalogue of the Etruscan gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. pp. 53-59

- ^ a b c Söderlind, Martin (2002). Late Etruscan votive heads from Tessennano: production, distribution, sociohistorical context. Volume 118 of Studia archaeologica. L'Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 35-41; 389-391

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, p. 122)

- ^ Mura Sommella (2008, p. 28)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, pp. 36–37)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, pp. 54–55)

- ^ Borrelli & Targia (2003, pp. 104–105)

- ^ Carpino, Alexandra Ann (2003). Discs of splendor: the relief mirrors of the Etruscans.. Wisconsin studies in classics. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 83-96

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art (ed.). "Carved amber bow of a fibula (safety pin)".

- ^ Strong, Eugénie S. Roman sculpture from Augustus to Constantine Ayer Publishing, p.30. ISBN 978-0-405-02230-2

- ^ Bardi, Ugo (1997/2002). The Chimaera of Arezzo Archived 2013-11-01 at the Wayback Machine. Università degli Studi di Firenze. (in Italian)

- ^ a b c d Stiebing, William H (1994). Uncovering the Past: A history of archaeology'. Oxford University Press US. pp. 153-165.

- ^ Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (1998). Aesthetics: lectures on fine art. Oxford University Press (reprinting). pp. 786-787

- ^ Ruskin, John (2008). Letters of John Ruskin to Charles Eliot Norton. Read Books. Volume 2. pp. 88-92

- ^ Braghine, Alexander (2004). The Shadow of Atlantis. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 182-183

- ^ Florman, Lisa (2002). Myth and Metamorphosis: Picasso's Classical Prints of the 1930s.. MIT Press. p. 19

- ^ Watkins, Nicholas (2007). From Fascism to the Bomb: Marino Marini and the undermining and destruction of the classical European horseman.. In Littlejohns, Richard & Soncini, Sara. Myths of Europe. Volume 107 of Internationale Forschungen zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft. Rodopi. pp. 238-241 ISBN 978-90-420-2147-1

- ^ a b Ross, Silvia (2007). The Myth of the Etruscans in Travel Literature in English. In Littlejohns, Richard & Soncini, Sara. Myths of Europe. Volume 107 of Internationale Forschungen zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft. Rodopi. pp. 263-274 (English) ISBN 978-90-420-2147-1

- ^ Lawrence, D. H. (2007). Etruscan Places. Read Books. p. 11 ISBN 978-1-4067-0400-6

- ^ Craddock, Paul (2009). Scientific Investigation of Copies, Fakes and Forgeries. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 197-199

- ^ a b Grummond, Nancy Thomson de (1996). Etruscan Italy Today. In Hall, John Franklin (ed). Etruscan Italy: Etruscan influences on the civilizations of Italy from antiquity to the modern era. Seth and Maurine Horne Center for the Study of Arts scholarly series. Indiana University Press. pp. 337-362

- ^ Izzet, Vediab (2007). The archaeology of Etruscan society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 16-19

Bibliography[edit]

- Bartoloni, Gilda (2008). "La revolución vil·lanoviana". Prínceps etruscos (in Catalan). Barcelona: Fundación La Caixa. ISBN 978-84-7664-975-6.

- Barral i Altet, Xavier (1986). Historia Universal del Arte. La antigüedad clásica, Volumen II (in Spanish). Barcelona: Editorial Planeta. ISBN 84-320-8902-8.

- Borrelli, Federica; Targia, Maria Cristina (2003). Etruscos: descubrimientos y obras maestras de la gran civilización de la Italia antigua (in Spanish). Barcelona: Electa. ISBN 84-8156-356-0.

- Mura Sommella, Anna (2008). "Els etruscos". Prínceps etruscos (in Catalan). Barcelona: Fundación La Caixa. ISBN 978-84-7664-975-6.

- Pallattino, Massimo (1984). Etruscologia. Storia, filosofia e religione (in Italian). Hoepli Editore. ISBN 978-88-203-1428-6.

- Staccioli, Romolo A. (1993). Como reconocer el arte etrusco (in Spanish). Barcelona: EDUNSA. ISBN 84-7747-077-4.