en

names in breadcrumbs

No specific information was found concerning any negative impacts to humans.

As a family, cichlids consume virtually every type of food source available in the freshwater habitat they are found. They exhibit numerous modifications of the lips, teeth, jaws and gill rakers depending on the main food source. Although many cichlids are morphologically adapted to a particular food source, they may become generalists depending on availability. Additionally, cichlids consume various types of food depending on their stage of growth. Herbivorous cichlids may browse, scrape, comb, ‘tap’ or suck epiphytic (attached) algae, unicellular algae, and/or clumps of the substrate. Planktivorous cichlids browse throughout the water column on zooplankton and phytoplankton. Piscivorous cichlids feed on whole fish, the fry, larvae, or eggs of mouthbrooding species, and the scales or fins of various fishes. Three species from the genus Cyrtocara (Lake Malawi) use the peculiar technique, termed head-ramming, of shoving their head into the mouth of female mouthbrooders to force the expulsion of eggs, larvae, or fry, which they eat. Cichlids that feed on aquatic insects and other invertebrates use a variety of methods to expose or capture prey. Several species (Labidochromis maculicauda, Tanganicodus irsacae) browse over patches of algae or substrate, picking out individual insects and crustaceans. Lethrinops (Lake Malawi) feed on chironomid larvae by biting into the sandy substrate and filtering the larvae out with their gill rakers. The enlarged lips of some cichlids are used to suck insects out of cracks and crevices, while in others the lips help to feel for prey when browsing over various substrates. In addition to the latter feeding methods, some cichlids have developed swimming patterns allowing them to sneak up on prey or use larger fish for cover. Finally, the teeth of some cichlids are predominantly molars, allowing them to crush and process small and thin-shelled mollusks. (See an illustration of tooth morphology and diversity in fish).

Foraging Behavior: filter-feeding

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore , Eats eggs, Eats body fluids, Eats non-insect arthropods, Molluscivore , Scavenger ); herbivore ; omnivore ; planktivore ; detritivore

In the Great Lakes of Africa, the number of cichlid species is so large they fill virtually every ecological role within their trophic level, with the exception of primary producers such as photosynthetic algae and benthic arthropods. As one might expect, there is considerable interplay between various cichlid species in terms of predation and food availability. However, cichlids also influence the species of plants and algae that grow in their habitat (top-down control). One example of top-down control is illustrated by the introduction of the piscivorous Nile perch into Lake Victoria. The Nile perch is a voracious predator of small, planktivorous cichlids, which suffered precipitous population decline after the perches’ introduction. Planktivorous cichlids exert considerable predation pressure on zooplankton, and after they were eliminated, the zooplankton community changed drastically, to the point that a new species of zooplankton began invading the lake, Daphnia magna.

Ecosystem Impact: biodegradation ; keystone species ; parasite

Several cichlid genera are popular aquarium fishes - Cichlasoma, Pterophyllum, Symphysodon, and jewelfishes - because of their mild temperament and ease of breeding in captivity. However, most cichlids are extremely aggressive when kept in small areas and very difficult to breed. Several Cichla species are popular with sport fishermen, especially in Brazil. Cichlids have also been introduced for recreational fisheries or vegetation control.

Some cichlids are used extensively in aquaculture for several reasons. They are a good source of ‘white fish’ and fish products, they lack small bones in the muscle, and some species can grow quite large, allowing for the production of value-added products such as fillets. Most importantly, they feed low on the food chain (aquatic plants and plankton) so the cost of feed is low. Oreochromis and Tilapia are the most extensively farmed cichlids. They are most widely grown in Israel and Asia but cichlid aquaculture has been introduced to many other regions: Egypt (Tilapia), Africa (Oreochromis), Latin America (Astronotus, Cichlasoma and Orechromis), and the Caribbean (Tilapia).

Positive Impacts: pet trade ; food ; research and education; controls pest population

Cichlids are mainly found in the lowland, freshwater areas of tropical and subtropical regions. However, some of the most primitive species, which are found in Madagascar (17 species) and Asia, also inhabit brackish waters. Some other areas with brackish-water species include coastal India and Sri Lanka (three species), and Cuba and Hispaniola (four species). The great majority of cichlids are found in the Great Lakes of East Africa (Lake Malawi, Lake Victoria, and Lake Tanganyika), where between 800 and 2100 species are thought to exist. Nearly all of these species are endemic (evolved in and confined to a particular place) to the lake they inhabit. There are approximately 150 river species in the region as well. The remaining distribution includes South America (approximately 290 species), Central America and Mexico (approximately 95 species), North America (one species), and the Middle East - Iran, Syria, Israel and Palestine (five species).

Cichlids have been widely introduced, either deliberately for aquaculture or accidentally through the aquarium trade (Lever, 1996). For instance, in the United States there is only one native species, the Rio Grande cichlid, but 44 species have been introduced. Florida has proven ideal for many exotic cichlids like the oscar, peacock cichlid, and Jack Dempsey, due to its warm climate and abundant water.

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Introduced , Native ); palearctic (Introduced , Native ); oriental (Introduced , Native ); ethiopian (Native ); neotropical (Native )

Most cichlids inhabit lakes or the sluggish areas of rivers but there are a few species adapted to swift flowing streams, including some Crenicichla species. Species in the genera Teleocichla and Retroculus, distributed in the highlands of Brazil and New Guinea, are also rheophilic (prefer flowing waters). In lakes there are few habitats cichlids do not occupy and there is an abundance of species filling virtually every ecological niche in some areas. For example, deepwater cichlids from Lake Tanganyika, Africa are able to survive in the permanently deoxygenated water layers for short periods. Individuals from the genera Tilapia and Oreochromis are also able to withstand low oxygen concentrations. Finally, some cichlids are tolerant of brackish waters. Oreochromis, Sarotherodon, and Tilapia are able to migrate along coastlines between rivers and some species, such as Oreochromis mossambicus, have become established in brackish and marine waters.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; saltwater or marine ; freshwater

Aquatic Biomes: pelagic ; benthic ; reef ; lakes and ponds; rivers and streams; coastal ; brackish water

Other Habitat Features: agricultural ; estuarine

The lifespan of many wild cichlids is unknown. However, in aquaria they are relatively long-lived, about 10 years on average. Several can reach up to 18 years in captivity, suggesting that at least some cichlids have considerably long lifespans.

Most cichlids are distinguished from all other freshwater fish by the existence of two unique features: a single opening of the nostrils and an interrupted lateral line. The two exceptions are Teleogramma and Gobiocichla, which have a continuous lateral line. The anal fin spines usually number three, but some species have four to nine anal fin spines and the Asian genus Etroplus has between 12 and 15. In general cichlids are relatively small in size but Boulengerochropmis microlepis and the Neotropical Cichla temensis reach approximately a meter in length. (Click here to see a fish diagram).

Superficially, there seem to be major differences in body shape across the Cichlidae family, with body shapes ranging from tubular, to perch-like, to disk-like, depending on habitat. For instance, Teleogramma, Gobiocichla, Teleocichla and Retroculus inhabit flowing waters and have elongate, tubular bodies, small, deeply imbedded scales and enlarged and thickened pelvic fins. Freshwater angelfish have extended dorsal and anal fins and discus fishes, have compressed, disc-like bodies. Finally, fast moving piscivorous cichlids, such as Crenicichla, Diplotaxodon, and Rhamphochromis, are elongate and streamlined. However, the fundamental cichlid morphology - position of the fins, arrangement of the jaws, and nature of the scales – remains consistent despite the wide variation in body forms.

The various components of the mouth together comprise some of the most intriguing physical features of cichlids. To begin with, the lips of several cichlid species are large and puffy, probably to help form a seal against irregular surfaces, so food can be sucked up (as in some detrivores). The outer jaw contains up to seven rows of teeth, which decrease in size moving toward the throat. The ancestral tooth shape is conical, but there are numerous variations depending on the diet of the fish. Some examples include stout, knife-like teeth for tearing up prey, teeth at right angles or in broad, file-like bands for ripping off the scales or flesh of other fish, flattened teeth with cusps for feeding on clumps of benthic algae, or brush-like teeth used to comb epiphytes (algae that grows on other algae) off filamentous algae. Most common, however, are flat, molar-like teeth, which come in a wide variety of shapes and are often mixed with other types of teeth. Next are the jaws, which are composed of a complex cage of bones around the skull connected by numerous muscles. The plasticity of the jaws in carnivorous cichlids allows individuals to create negative pressure, effectively sucking the prey toward them, or to extend one part of the jaw independent of the other, so individuals can grasp prey below them. The gill rakers lie just behind the jaws and vary considerably depending on intended prey. In piscivorous cichlids, the gill rakers are short, sturdy and sharp while planktivores and detrivores have numerous, long, thin and tightly packed gill rakers for filtering out food particles. Other cichlids have true teeth on the gill rakers, which aid in the processing of prey. Finally, the pharyngeal jaw apparatus contains yet another set of teeth, which, as with the outer jaws, contain a wide variety of tooth types depending on the diet. The pharyngeal jaw also frees up the outer jaw from chewing, allowing more prey to be captured while the previous meal is being processed (See Food Habits for more details).

Sexual dimorphism occurs in some cichlids, and is most common in polygynous mouthbrooders and harem-forming species. Typically, males are larger than females and males exhibit more elaborate coloration. An extreme case of size dimorphism can be found in the harem-forming ,Neolamprologus callipterus. Males can be up thirty times the size of the miniscule females; this is the largest margin known for any vertebrate animal by which males outsize females. Apistogramma also exhibits sexual dimorphism, as males are strikingly colored and lavishly ornamented with elongated filaments on the spines of their dorsal and anal fins, and on the tails and pelvic fins. Most monogamous cichlids are virtually indistinguishable, although males are larger than females on average. During spawning, however, the foreheads of males swell in some species, such as Midas cichlids, or the sexes may take on different coloration (dichromatic). In an odd departure from the usual sexual dimorphism (with males being more colorful), female convict cichlids display gold colors on the lower half of the midsection of the body (where the egg sac is located) to attract males. Since this discovery, numerous examples of “reverse dichromatism” have been found in other cichlid species.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Sexual Dimorphism: sexes alike; male larger; sexes colored or patterned differently; female more colorful; male more colorful; sexes shaped differently; ornamentation

Many large cichlids prey on smaller members of their family or specifically feed in eggs, larvae, or fry. Investigators have also observed newly independent juveniles preying on young of the same or related species. These predation pressure help explain the evolution of intense parental care in cichlids. Introduced species, such as Nile perch, have proven disastrous for many endemic cichlids, even causing the extinction of some species (See Ecosystem Roles and Conservation Status). Humans have also exploited cichlids throughout their range for centuries.

Known Predators:

Anti-predator Adaptations: mimic; cryptic

The Cichlidae family stands out as an extraordinary example of vertebrate evolution. From the sheer size of the family to the complexity of their ecological interactions and rapid evolution, cichlids provide a unique glimpse of the many factors that promote speciation. The behavioral and physical changes resulting from intense speciation in cichlids is equally impressive. Cichlids demonstrate some of the most unique and intensive parenting in fishes and utilize several different mating systems, from monogamy to polygynandry (See Reproduction). Many feeding behaviors found in cichlids are unique among freshwater fishes (See Behavior and Food Habits). Finally, although the general body plan of cichlids is constant, they come in a dazzling array of shapes, sizes, colors, and dental plans, making them popular with aquarists and aquaculturists (See Physical Description and Economic Importance to Humans).

There are no concrete figures on the number of genera and species in the Cichlidae family because there are still many revisions being made and a considerable number of species are yet to be described. Rough estimates range from 200 to 2000 species and approximately 140 genera, which, after Cyprinidae and Gobiidae, would make them the third largest family of bony fishes. The largest genus is the African Crenicichla with over 100 species. Cichlids inhabit fresh waters, and many species are endemic to isolated lake environments. The fact that no genera occur on more than one continent illustrates the degree of endemism in this family.

Because many cichlid species are endemic to small geographic areas, they can be threatened relatively easily. Many cichlid species will never be described because they are going extinct so quickly. Such is the case with cichlids of Lake Victoria after the introduction of Nile perch. Nile perch were introduced as a food source (unsupervised) but, as a voracious predator, began to destroy cichlid populations throughout the lake. This has resulted in the largest mass extinction of endemic species in recent times. Conservative estimates are that across the Cichlidae family, 43 cichlids are extinct, five are extinct in the wild, 37 species are critically endangered, 11 species are endangered, 34 species are vulnerable, and one species is at low risk.

Cichlids are able to communicate by various means: visual, acoustic, chemical and tactile. Visual communication primarily involves color changes and body movements and gestures. At least some cichlids are able to discern colors. Color changes are important in identifying individuals or families, or for communicating aggression, dominance, or sexual state. Typically, the brightest color patterns are associated with aggression. Body movements and gestures are also used to communicate aggression, dominance, or sexual state, and often combine with swimming patterns and color changes to emphasize a particular display. Tactile communication is mainly observed in aggressive males, such as the case of “mouth-fighting.” Tropheus moorii males lock mouths until one individual is pushed to the bottom and flees. In some mouthbrooding species (Simochronis and Tropheus) males often touch the anal region of the female as she begins to expel her eggs, presumably encouraging the female to lay her eggs. Sounds, such as grunts, thumps or purrs have been catalogued for at least 16 cichlid species. Experiments with one cichlid, Archocentrus centrarchus, have revealed that recorded sounds (produced during aggressive displays) evoked an aggressive response. Cichlids are known to use chemical cues to recognize their young in parenting. For example, Amatitlania nigrofasciata and Amphilophus citrinellus are able to discriminate their own small fry from those of other species. The reverse is also true; Amphilophus citrinellus fry are able to distinguish chemical cues given off by their parents. Etroplus maculates and Etroplus suratensis, which feed on fry, use chemical signals to avoid eating fry of the same species. Finally, monogamous pairs of some species need both visual and chemical cues to recognize each other.

Communication Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; chemical

Other Communication Modes: mimicry ; pheromones ; scent marks ; vibrations

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; acoustic ; vibrations ; chemical

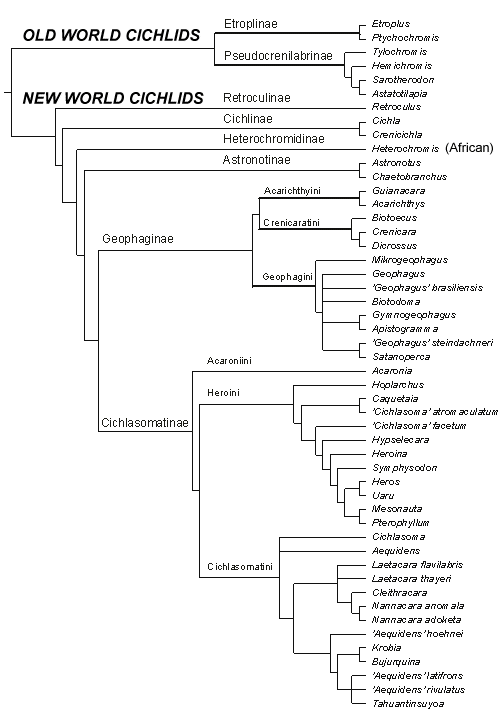

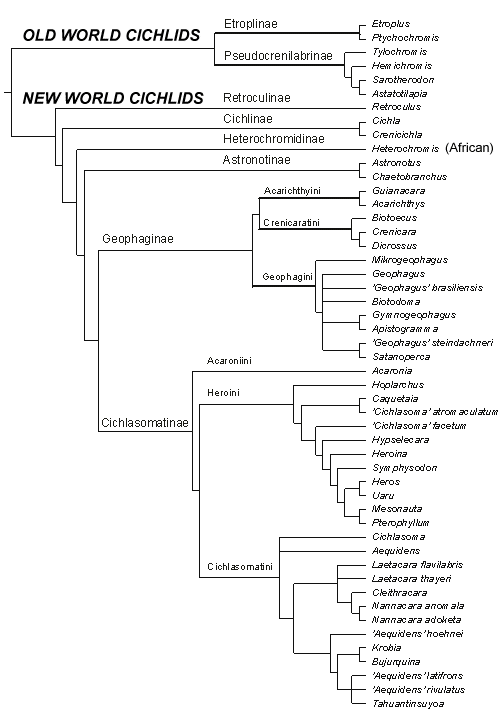

The earliest known cichlid fossils were collected in South America, dating back to the Eocene (57 to 37 million years ago), and in Africa, dating back to the Oligocene (33.7 to 23.8 million years ago). However, the fossil history is poor and it is widely believed that the cichlids, along with other labroid families, arose sometime early in the Cretaceous epoch (144 to 66.4 million years ago). Despite the paucity of fossils, investigators have identified several existing Malagasy and Asian genera as the least derived within the Cichlidae. Researchers have gained a good understanding of the evolutionary biology of cichlids from this discovery. For instance, substrate brooding is considered the ancestral breeding system because it is practiced by the oldest genera in Madagascar and Asia.

Cichlids follow a typical developmental pattern but some species brood the eggs in the mouth while developing. Parents exhibit various behaviors to promote the growth of young, which develop through three distinct stages: eggs, wrigglers (newly hatched, non-free-swimming young), and fry (free swimming but dependent on the parent). At the early stages of development, parents fan the eggs to provide ventilation and remove waste (termed “fanning”). Some species use their mouths to suck away wastes or to remove dead or fungus-ridden eggs (termed “mouthing”). Mouthbrooding species that carry developing eggs in the buccal cavity (mouth) accomplish mouthing and fanning by rolling and swishing the eggs in the mouth (termed “churning”). Finally, several behaviors are related to aiding the young in feeding. Parents may pick up leaf matter and drop it near the young so they may forage on the unexposed side (termed “leaf-lifting”), or dig into the substrate with the fins to expose buried prey (termed “findigging”). Another unusual method of aiding the fry in development is “micronipping,” in which fry feed on mucous secreted from the skin of parents. Micronipping was first discovered in Symphysodon discus, but has since been recorded for several other cichlid species.

Some species of blue tilapia (among others), which are widely used in aquaculture, are susceptible to sex change for a period approximately 30-40 days after hatching by controlling temperature or adding hormones (See Mating Systems). Despite the fact that genetics also influence sex determination, hormones and temperature can overrule genetic determination, creating offspring that are all one sex. Aquaculturists take advantage of this fact to create single sex tanks, thus avoiding overpopulation.

Development - Life Cycle: temperature sex determination

The diversity of habitats occupied by cichlids is matched by the number of mating systems they employ. In fact, the local ecological conditions are an important indicator of the mating system used, which may vary within the same species. The most primitive condition is monogamy, with males and females essentially monomorphic, excepting some coloring details. Courtship rituals and parental care are common among monogamous pairs. Some cichlids are polygynous: males fertilize the eggs of more than one female. In this system, males might defend a territory that females visit to spawn (only once during the season), two females may defend a territory overlapping that of a male (bigamy), or a male may dominate a harem of multiple females. Cichlids also employ polyandry, in which females mate with several males. In one extraordinary case, sex roles are essentially reversed. Sarotherodon melanotheron males nurture eggs and fry in the mouth for 15 days after spawning, while females are capable of spawning just a week later. This creates a situation where the availability of males to brood the eggs is the limiting factor in reproduction. Behavioral studies reveal that male Sarotherodon melanotheron are less aggressive, and more selective, choosing larger females. Next, some cichlids may be promiscuous (polygynandrous).

An intriguing form of promiscuous spawning in some planktivorous cichlids (and at least one non-planktivorous cichlid as well) is termed “lekking,” a Swedish word meaning “to play.” Amazingly, from 5,000 to 50,000 males may congregate during lekking, which occurs over a long breeding season in some cichlids. Some lekking species, such as Copadichromis eucinostomous, migrate inshore and build volcano-like nests out of sand , while others lek in open waters, such as Paracyprichromis brieni. Females then mate with between 4 and 12 males, distributing a few eggs to each. A final mating system, termed “extended family” is found in at least one cichlid species, Neolamprologus multifasciatus. In this scenario, there are colonies of approximately 19 individuals (one to three males, up to five females, and the rest juveniles) with a large dominant male (alpha) and one other male (beta) participating in spawning. A number of individuals in each colony are related (outsiders may occasionally join a colony) and there are overlapping generations within each colony.

In Lake Tanganyika, Neolamprologus tetracanthus illustrates the utility of multiple mating systems in a dynamic environment. In one habitat, where the bottom is barren and predators are abundant, Neolamprologus tetracanthus males remain with their spawning partner to guard the fry. In a different part of the lake, predators are less abundant and populations are larger. There, numerous females establish individual feeding areas and male territories encompass as many as 14 females. The males spawn with each female and exhibit no parental care – an extreme case of polygyny. Numerous other studies support the existence of “plastic” mating strategies among cichlids. St. Peters fishes, of northern Africa, Israel and Jordan, illustrate how distinctions between mating systems are blurred by a single pair of spawning cichlids. Pairs form after a prolonged courtship ritual. After the eggs are fertilized, they may be taken by the male, female, or both as they go their separate ways. The parent that doesn’t take the eggs is free to spawn again. Finally, in harem-forming species and lekking mouth-brooders, smaller or weaker males may attempt to covertly fertilize a female—variously called sneaking, cheating, or parasitic spawning. During lekking males may accomplish this by mimicking females. Parasitic spawning is rare among monogamous species, probably because males and females remain in close proximity while spawning.

Mating System: monogamous ; polyandrous ; polygynous ; polygynandrous (promiscuous) ; cooperative breeder

There are two general modes of cichlid reproduction: substrate brooding and mouthbrooding. Substrate brooding (or nest building) represents the initial (evolutionarily) reproductive strategy, evidenced by the fact that the most primitive species are substrate brooders (See Other Comments). Substrate brooders tend to be monogamous and sexually monomorphic. The egg sacs usually adhere to hard surfaces and the helpless larvae (termed wrigglers), which have large yolk sacs, remain guarded in the nest until they can swim (and are then termed fry). The nests of substrate brooders range from sand castles to sand craters to accumulations of snail shells. Most mouthbrooders are polygynous and sexually dimorphic , although several species are monogamous. The eggs and wrigglers are carried in the mouth of the female , or in monogamous species, both males and females carry larvae in their mouths. As one might expect with such a diverse group of fishes, there is wide variation between the two general patterns described above (See Reproduction: Mating Systems). Many cichlids mate year round and the number of eggs ranges from just a few to several hundred across the family.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; year-round breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sequential hermaphrodite; sexual ; fertilization (External ); oviparous

Parental care is likely the most intriguing life history feature of cichlids. Cichlids are well known for their strategy of mouthbrooding, in which the eggs, wrigglers (newly hatched, non-free-swimming young), or fry are carried in the mouth of an individual. In some mouthbrooding species there is no contact with the substrate; the unfertilized eggs are carried in the mouth of the male or female (termed immediate or ovophilic parental care). In others, the eggs are adhered to a substrate, fertilized and taken into the parents mouth after hatching (termed delayed or larvophilic parental care). Female (maternal) mouthbrooding is most common and well known but in at least one species, Sarotherodon melanotheron, the male carries the young (paternal mouthbrooding). In several other species mouthbrooding is biparental, shared by the male and female. Substrate brooders also guard their young, usually in some cooperative parenting system, such as biparental monogamy. Substrate brooding species also expend considerable energy caring for young. The eggs are initially attached to a substrate where they are cared for intensively. The newly hatched wrigglers may be transferred to a newly excavated pit, a patch of leaves, or the rootlets of aquatic vegetation where they are suspended by threads of mucous. The fry move along the substrate feeding on small particles while the parents keep guard.

In both substrate and mouthbrooding species parents use physical movements (termed “calling behaviors”), such as flicking the pelvic fins or jogging the head, when predators approach. These movements serve as cues for fry to retreat, either settling to the substrate near the parent or entering the mouth depending on the type of parental care. Experiments have shown that the level of vulnerability of young is the main determinant of continued parental care, rather than a set time period after hatching. Several other behaviors relating to parental care are described in Development.

Parental Investment: male parental care ; female parental care

Cichlidae is 'n groot visfamilie van die orde Perciformes. Spesies van die familie leef in vars- sowel as brakwater. Dié familie word gevind in Sentraal - en Suid-Amerika, Afrika, Madagaskar en dele van Indië en Arabië en speel ook 'n belangrike rol as 'n voedingsvis. Cichlidae is die grootste visfamilie in Afrika met ongeveer 900 spesies.

Die volgende genera en gepaardgaande spesies is deel van die familie:

Cichlidae is 'n groot visfamilie van die orde Perciformes. Spesies van die familie leef in vars- sowel as brakwater. Dié familie word gevind in Sentraal - en Suid-Amerika, Afrika, Madagaskar en dele van Indië en Arabië en speel ook 'n belangrike rol as 'n voedingsvis. Cichlidae is die grootste visfamilie in Afrika met ongeveer 900 spesies.

Los cíclidos (Cichlidae) son una familia de peces del orde de los Perciformes de la clase pexes óseos. Los cíclidos son una familia de gran ésitu evolutivu, mayormente d'agua duce, y son bien curiosos pa l'acuariofilia, pos son de los pexes más solicitaos por espertos nesta práutica. Cada añu atópense numberoses especies nueves, y munches d'estes entá non descrites. El númberu real d'especies nesta familia nun ta claro, por cuenta d'envaloraos que varien de 1300 a 3000 especies, que tienen gran diversidá de formes y carauterístiques úniques, que faen d'esta una de les families más grandes de vertebraos. La mayoría de les especies d'esta familia tien un promediu de vida de 10 a 20 años.

Munchos cíclidossobremanera la tilapia, son importantes nel comerciu d'alimentos, ente qu'otros, como los ánxeles, los discos y los óscares, son bien valoraos nel comerciu de la acuariofilia. Esta familia ye tamién la familia de vertebraos con más especies en peligru d'estinción, munches de les cualos atópense nel grupu de Haplochromis.

Los cíclidos, amás de ser bien importantes pal comerciu y l'economía, ser tamién pal estudiu de la evolución d'especies na ciencia, porque evolucionaron bien rápido un gran númberu d'especies bien rellacionaes, pero con carauterístiques morfolóxiques bien diverses dientro de los grandes llagos d'África (Malawi, Tanganica, Victoria y Eduardo).

Munchos cíclidos que fueron accidental o deliberadamente distribuyíos en llibertá nes agües fora de la so área natural, convirtiéronse n'especies dañibles; por casu, la tilapia nel sur de los Estaos Xuníos. Esto ye por cuenta de la so gran adaptación a cuasi cualquier ecosistema, y pol so territorialidad. Esto provoca que los cíclidos cómanse, fadien o dexen ensin alimentu a los demás habitantes; poro, altériase l'ecosistema, lo cual ye bien perxudicial.

Los cíclidos tienen gran diversidá de formes y carauterístiques úniques, y tienen una amplia variedá de tamaños, que van dende 25 mm nel casu de Neolamprologus multifasciatus hasta especies de 1 m de llargu. Igualmente, los cíclidos presenten una amplia diversidá de formes del cuerpu, que van dende bien estruyíos lateralmente (como lo son les especies d'ánxeles, discos, Altolamprologus, etc.) hasta con forma cilíndrica (como los Julidochromis). Un grupu d'especies suel tener carauterístiques asemeyaes en tamañu y forma según el so ecosistema y otres necesidaes. Un exemplu d'esto ser los mbuna, que son, polo xeneral, llixeramente estruyíos, de tamañu mediu y cuerpu asemeyáu.

Toles especies comparten una carauterística clave: tienen un par de quexales faríngeas, qu'ayuden a les quexals orales nel so trabayu. Por cuenta de esto, pueden prindar y procesar una amplia variedá d'alimentos, siendo esta una de les esplicaciones de la so variedá de formes corporales.[1][2]

Les carauterístiques que los estremen d'otros Labroidei inclúin:[3]

Los cíclidos atopar dende agües negres, acedes y blandes (como'l ríu Negru), a agües dures y alcalines (como'l llagu Tanganica), o, inclusive, nes agües salobres de les desaguaes de los ríos. La gran mayoría tán en zones tropicales. La gran mayoría habita n'agua duce, pero esisten especies d'agua salao y salobre, anque munches de les especies d'agua duce toleren l'agua salobre mientres llargos periodos (por casu, Cichlasoma urophthalmus). Puede atopase vida y la cría n'ambientes d'agua salao, como desaguaes de los ríos, les petrines de manglares alredor de la barrera d'islles. Delles especies de tilapias (tilapia, Sarotherodon, y Oreochromis) son resistentes a agües salobres, y pueden esvalixase a lo llargo de les costes ente dellos ríos salobres.

Trátase principalmente de pexes d'agua duce, mayormente d'África (de los llagos Malawi, Tanganica, Victoria y Eduardo) y América del Sur (del ríu Amazones). Calcúlase que, ente toles especies descrites, sumaes a les qu'entá nun s'afayaron, va haber a lo menos 1600 especies namái n'África. Tamién s'atopa un gran númberu en Mesoamérica, dende Panamá, en Centroamérica, hasta la porción mexicana d'América del Norte (teniendo como frontera más septentrional el ríu Bravo, nel sur de Texas), con aproximao 120 especies. Madagascar tien la so propia fauna de cíclidos, filogenéticamente alloñada en rellación colos del continente africanu. N'Asia namái s'atopen 4 especies nel abargane de Xordania nel Oriente Mediu, 1 n'Irán, y 3 n'India y Sri Lanka. Hai 3 especies que s'atopen en Cuba y La Española. N'Europa, Australia, Antártida y América del Norte, al norte del ríu Grande, nun hai nenguna especie nativa de cíclidos, anque les condiciones ambientales son afeches. En Xapón y el norte d'Australia, los cíclidos estableciéronse como animales amontesaos.

La so alimentación depende del llugar xeográficu de procedencia: esisten cíclidos omnívoros y cíclidos herbívoros. En llibertá, xeneralmente aliméntense de pequeños crustáceos, algues, y pequeños pexes. En cautiverio ye bien recomendable optar por una alimentación de gama profesional, dexando les games comerciales pa especímenes menos esixentes nutricionalmente. Ye bien importante que la calidá de les algues, escames o granosu seya bien bona, yá que, si non, son propensos a tener problemes dixestivos.

Polo xeneral, los cíclidos tienen fama d'agresivos y territoriales. Magar hai especies que se salten esta norma, la gran mayoría tienen ciertu grau d'agresividá escontra otros pexes que s'enfusen nel so territoriu. Según les especies, hai con territoriu permanente, con territoriu namái en dómina de cría, o totalmente gregarios. Los machos de la mesma especie nun suelen aceptase.

Tienden a formar pareyes que caltienen pa tola vida, o harénes (más dinámicos).

Hai dellos tipos de cíclidos:

Daqué no que destaquen estos pexes ye nos cuidos que dediquen a la proxenie. Van Defender con bravura la puesta (que nun ye bien numberosa comparada cola de los pexes que se despreocupan de los güevos), inclusive contra enemigos de muncho mayor valumbu. La gran mayoría va curiar de los esquiles mientres aproximao un mes.

Tocantes a los llugares de puesta, hai de too: en cueves, na superficie de piedres, en fuexos cavaos por ellos mesmos, sobre fueyes, etc. Anque cabría destacar, en delles especies de cíclidos, la evolución que los llevó a guarar los güevos na so propia boca, asegurando una mayor supervivencia, anque a cuenta de un menor númberu de güevos.

Munches de les especies africanes utilicen como métodu de cría la incubación bucal, que consiste en caltener protexíes a les críes na boca de la madre hasta qu'algamen un tamañu abondu pa ser lliberaes.

En 2007, según la Unión Internacional pal Caltenimientu de la Naturaleza (UICN) y la Llista Colorada de los Recursos Naturales, 156 especies de cíclidos tán incluyíes como «especies vulnerables», 40 especies tán «en peligru d'estinción», y 69 especies tán llistaes como «críticamente en peligru d'estinción». 6 especies (Haplochromis ishmaeli, Haplochromis lividus, Haplochromis perrieri, Paretroplus menarambo, Platytaeniodus degeni y Yssichromis sp. nov. 'argens') escastáronse na naturaleza, ente que siquier 39 especies (la mayoría del xéneru Haplochromis) escastáronse dende empiezos del deceniu de 1990.

Dellos xéneros de la familia Cichlidae tán inda Incertae sedis, esto ye, a la espera d'una clasificación nes distintes subfamilies. Estos xéneros son:

Los cíclidos (Cichlidae) son una familia de peces del orde de los Perciformes de la clase pexes óseos. Los cíclidos son una familia de gran ésitu evolutivu, mayormente d'agua duce, y son bien curiosos pa l'acuariofilia, pos son de los pexes más solicitaos por espertos nesta práutica. Cada añu atópense numberoses especies nueves, y munches d'estes entá non descrites. El númberu real d'especies nesta familia nun ta claro, por cuenta d'envaloraos que varien de 1300 a 3000 especies, que tienen gran diversidá de formes y carauterístiques úniques, que faen d'esta una de les families más grandes de vertebraos. La mayoría de les especies d'esta familia tien un promediu de vida de 10 a 20 años.

Munchos cíclidossobremanera la tilapia, son importantes nel comerciu d'alimentos, ente qu'otros, como los ánxeles, los discos y los óscares, son bien valoraos nel comerciu de la acuariofilia. Esta familia ye tamién la familia de vertebraos con más especies en peligru d'estinción, munches de les cualos atópense nel grupu de Haplochromis.

Los cíclidos, amás de ser bien importantes pal comerciu y l'economía, ser tamién pal estudiu de la evolución d'especies na ciencia, porque evolucionaron bien rápido un gran númberu d'especies bien rellacionaes, pero con carauterístiques morfolóxiques bien diverses dientro de los grandes llagos d'África (Malawi, Tanganica, Victoria y Eduardo).

Munchos cíclidos que fueron accidental o deliberadamente distribuyíos en llibertá nes agües fora de la so área natural, convirtiéronse n'especies dañibles; por casu, la tilapia nel sur de los Estaos Xuníos. Esto ye por cuenta de la so gran adaptación a cuasi cualquier ecosistema, y pol so territorialidad. Esto provoca que los cíclidos cómanse, fadien o dexen ensin alimentu a los demás habitantes; poro, altériase l'ecosistema, lo cual ye bien perxudicial.

Tsixlosomlar (lat. Cichlidae) — Xanıkimilər dəstəsinə aid balıq fəsiləsi. Bu fəsiləyə daxil olan 1300-ə yaxın növ təsnif olunub, təsnif olunmamış növlərin sayı isə 600-dən çoxdur.

Els cíclids (Cichlidae) són una família de peixos d'aigües dolces tropicals pertanyent a l'ordre dels perciformes, algunes espècies de la qual són molt apreciades com a peixos d'aquari (especialment els gèneres Cichlasoma, Aequidens, Pseudotropheus, Aulonocara, Julidochromis, Pterophyllum i Symphysodon).[2][3][4]

Són de dimensions mitjanes, tot i que Boulengerochromis microlepis pot assolir els 80 cm de longitud màxima. La forma del cos és molt variable però, generalment, és allargada o ovalada i comprimida lateralment. Coloració de tons apagats en alguns i vistosa en uns altres. Tenen una sola aleta dorsal, la part anterior de la qual té radis espinosos. Tenen un orifici nasal a cada costat del cap. Interrupció de la línia lateral en la majoria de les espècies. Entre 3 i 15 espines a l'aleta anal (generalment, 3). Els mascles solen ser més grossos i amb les aletes més allargades que les femelles.[5][6][7][8]

Segons l'espècie, poden ser omnívors o herbívors.[6][10]

Viuen en les aigües de vegetació abundant[11] de Sud-amèrica (290 espècies), Amèrica Central, Texas (1), les Índies Occidentals, Àfrica (900), Madagascar (17), el sud de l'Índia, Sri Lanka, la vall del riu Jordà (4) i l'Iran (1).[6][12][11]

Molts cíclids adults, si tenen l'oportunitat, poden depredar els membres més joves de la seva pròpia espècie (ous, larves i alevins) o d'altres espècies de cíclids. Aquesta pressió depredatòria ajuda a explicar la intensa atenció dels pares envers la seua progènie. Així mateix, les espècies introduïdes(com la perca, per exemple) han resultat desastroses per a molts cíclids endèmics fins a l'extrem de causar l'extinció d'algunes espècies. Els éssers humans també han exercit una intensa pressió sobre aquesta família de peixos al llarg dels segles.[13]

Els cíclids són àmpliament emprats en aqüicultura per al consum alimentari humà. Així, per exemple, a Israel i Àsia els gèneres Oreochromis i Tilapia són molt populars; a l'Amèrica Llatina els gèneres Astronotus, Cichlasoma i Oreochromis; al Carib i a Egipte, les espècies del gènere Tilapia; i a la resta d'Àfrica, Oreochromis.[14]

Els cíclids (Cichlidae) són una família de peixos d'aigües dolces tropicals pertanyent a l'ordre dels perciformes, algunes espècies de la qual són molt apreciades com a peixos d'aquari (especialment els gèneres Cichlasoma, Aequidens, Pseudotropheus, Aulonocara, Julidochromis, Pterophyllum i Symphysodon).

Vrubozubcovití (Cichlidae, česky též cichlidy) je čeleď ostnoploutvých paprskoploutvých ryb ze sladkých vod Jižní a Střední Ameriky, Afriky a Asie. U cichlid je silně vyvinuta péče o potomstvo.

Vrubozubcovití se přirozeně vyskytují v Jižní a Střední Americe (na severu až po Rio Grande), Africe a v několika druzích i v Asii od Izraele po Indii a Srí Lanku.

Rody vrubozubcovitých[1]:

Cichlidy jsou jikernaté ryby, třou se, obvykle v párech, a kladou jikry. V akváriích však jsou velmi často pozorována tření několika jedinců najednou. Jde především o ryby z afrických jezer Malawi a Tanganjika.

Jihoamerické cichlidy se o jikry a potěr většinou velice pečlivě starají. Podle toho, který z rodičů se o potomstvo stará a jak mají rodiče rozděleny funkce, se u různých druhů cichlid dá rozlišit pět základních typů rodin. V rodině rodičovského typu se o potomstvo starají oba rodiče podobným způsobem. V rodině typu otec–matka se o potomstvo stará pár společně, mají ale výrazně rozdělené role, samec obvykle hlídá teritorium. V harémové rodině se samec vytírá s více samicemi, z nichž si každá udržuje vlastní teritorium, ve kterém se o potomstvo stará, zatímco samec hlídá velké teritorium zahrnující teritoria samic. V rodině mateřského typu se o potomstvo stará jen matka. Rodina otcovského typu, ve které se o potomstvo stará pouze otec, je u cichlid spíše výjimkou. Rodiče jsou při odchovávání plůdku daleko agresivnější než mimo období rozmnožování.

U některých cichlid se vyvinula velmi specializovaná péče. Řada jihoamerických i afrických druhů přechovává jikry i plůdek v tlamě. Plůdek terčovců – rod Discus se živí kožním sekretem rodičů. Ten dosud nebyl v žádné laboratoři napodoben, proto cena těchto ryb je značně vysoká.

Ryby z afrických jezer Malawi a Tanganjika se rozmnožují tak, že jeden dominantní samec v hejnu se tře se všemi samicemi. Jikry a plůdek uchovává matka v tlamce po celou dobu vývoje plůdku. Traduje se, že po tuto dobu nepřijímá potravu, ale není tomu tak – v zajetí byly mnohokrát pozorovány samice, které v období nošení plůdku v tlamě přijímaly potravu.

Terčovci se oproti jiným druhům starají o potomstvo střídavě. Několik hodin je plůdek přichycen na kožním sekretu třeba otce a po několika hodinách sebou otec škubne a plůdek jako na povel přepluje na druhého rodiče.

Česko patří s Malajsií, Tchaj-wanem a několika dalšími zeměmi k nejdůležitějším producentům akvarijních ryb na světě.

Vrubozubcovití (mezi akvaristy známější pod jménem cichlidy) patří k nejoblíbenějším akvarijním rybám. Jihoamerické skaláry a terčovci patří k nejznámějším akvarijním rybám vůbec. Velmi oblíbené jsou rovněž drobné jihoamerické cichlidky a endemičtí tlamovci z východoafrických jezer Tanganika a Malawi.

Chov i odchov méně náročných cichlid je relativně jednoduchý a vhodný i pro začínající akvaristy. Mezi cichlidy ale patří i řada velmi náročných ryb. Například známí terčovci jsou velmi choulostiví a vyžadují odbornou péči. Cichlidy z východoafrických jezer jsou velmi náročné na parametry vody a její znečištění dusíkatými látkami.

Vrubozubcovití (Cichlidae, česky též cichlidy) je čeleď ostnoploutvých paprskoploutvých ryb ze sladkých vod Jižní a Střední Ameriky, Afriky a Asie. U cichlid je silně vyvinuta péče o potomstvo.

Ciclider er fisk fra familien Cichlidae af ordenen Perciformes. Familien er omfattende med stor diversitet og mindst 1.650 arter er blevet beskrevet. Dermed hører familien til en af de største inden for hvirveldyrene og nye arter opdages hvert år. Mange er endnu ikke beskrevet, hvorfor det endelige antal arter er ukendt; men det vurderes at der findes 2.000 til 3.000 arter. Ciclider er meget udbredt inden for akvariehobbyen, fordi mange arter er meget farverige eller har en interessant adfærd. Enkelte ciclider har betydning som spisefisk.

Ciclider har en mangfoldighed af kropsbygninger og findes i størrelser fra 2,5 centimeter til næsten 1 meters længde. Hovedparten af arterne er af medium størrelse, ovale i form og lidt sideværts komprimeret, og kan minde om små udgaver af aborren. Nogle arter har en mere fladtryk og skiveformet krop. Andre arter har en langstrakt cirkulær krop.

Det største antal arter findes i tropisk Afrika, hvoraf en stor del lever i de store afrikanske søer (Malawi, Tanganyika og Victoria). Omkring 400 arter lever i Mellem- og Sydamerika. Enkelte arter forekommer omkring Cuba og Hispaniola, mens en enkelt art er er hjemmehørende i Texas, USA.

17 arter forekommer på Madagaskar, og i Asien forekommer der 15 arter, som lever i Indien og Sri Lanka. En enkelt art findes i den sydlige del af Iran og syv eller otte arter forekommer i Israel og Jordan (Jordandalen).

Generelt er ciclider ferskvandsfisk, men nogle arter tåler brakvand og kan f.eks. leve i mangroveområder. Det gælder særligt arter fra Indien, Madagaskar, Cuba og Hispaniola.

Kosten for ciclider spænder meget vidt. Nogle ciclider er deciderede rovfisk, andre er planktonspisere og endelig er der arter, som udelukkende lever af planter. Enkelte arter er meget specialiserede og lever af skæl eller øjne fra andre fisk, som de angriber.

Ciclider har generelt en udviklet yngelpleje, og de fleste arter afsætter deres æg på et substrat hvorefter den ene eller begge forældre vogter æggene. Nogle arter er mundrugende, hvor en af forældrene opbevarer æggene i mundhulen efter de er lagt og befrugtet. Når æggene er udklækket, kan larverne udvikles i mundhulen.

Discusfisken er kendt for en særlig form for yngelpleje, idet forældrene udskiller et særligt slimlag, som ungerne spiser af, de første uger efter de er kommet ud af ægget.

Visse ciclider af slægten Tilapia opdrættes i store dele af verden som spisefisk. Det er den tredje mest betydningsfulde fisk i akvakulturer, hvilket skyldes fiskens hurtige tilvækst og høje indhold af protein. Hertil kommer at fisken i modsætning til f.eks. laks og ørred kan opdrættes med vegetabilsk foder. Den største produktion af Tilapia sker i Kina. Slægten stammer oprindeligt fra Afrika.

Ciclider er populære akvariefisk, og mange arter er lette at holde i et akvarium. Scalaren og Discusfisken er avlet i årtier, og derved er fremkommet et stort antal kulturtyper med iøjnefaldende farver eller mønstre. Interessen for ciclider tog et stort spring i 1970'erne og 1980'erne, da mange spændende arter fra de store afrikanske søer blev tilgængelige i handlen.

Ciclider er fisk fra familien Cichlidae af ordenen Perciformes. Familien er omfattende med stor diversitet og mindst 1.650 arter er blevet beskrevet. Dermed hører familien til en af de største inden for hvirveldyrene og nye arter opdages hvert år. Mange er endnu ikke beskrevet, hvorfor det endelige antal arter er ukendt; men det vurderes at der findes 2.000 til 3.000 arter. Ciclider er meget udbredt inden for akvariehobbyen, fordi mange arter er meget farverige eller har en interessant adfærd. Enkelte ciclider har betydning som spisefisk.

Buntbarsche (Cichlidae) oder Cichliden sind eine Familie der Knochenfische aus der Gruppe der Barschverwandten (Percomorphaceae). Nach den Karpfenfischen (Cyprinidae) und den Grundeln (Gobiidae) bilden die Buntbarsche mit etwa 1700 beschriebenen Arten die drittgrößte Fisch-Familie. Viele Arten sind wegen ihres farbenprächtigen Äußeren, des komplexen Verhaltensspektrums und der einfachen Pflege beliebte Aquarienfische,[1] einige große Arten sind wichtige Speisefische.

In der Evolutionsbiologie hat die Untersuchung der Cichliden wesentlich zum Verständnis der Mechanismen der Artbildung beigetragen. Die Artenschwärme der Buntbarsche im Victoriasee und ihrer Verwandten in den benachbarten Afrikanischen Großen Seen können als Modell für eine relativ rasche Artenentwicklung betrachtet werden. Zudem sind Buntbarsche bedeutende Forschungsobjekte in der Verhaltensbiologie.[1]

Buntbarsche bewohnen mit etwa 1100 beschriebenen Arten den größten Teil des tropischen Afrikas; weitere 200 bisher unbeschriebene Arten werden hier vermutet. Allein in den ostafrikanischen Seen Malawi, Tanganjika (350 Arten) und Viktoria (250–350 Arten) kommen jeweils mehrere hundert Arten vor. Hier stellen sie den Hauptbestandteil der Fischfauna. Etwa 570 Arten leben in Mittel- und Südamerika, vier auf Kuba und Hispaniola, eine auch in Texas. 29 Arten, die stark in ihrem Bestand gefährdet sind, leben auf Madagaskar. In Asien sind die Buntbarsche mit nur elf bis zwölf Arten vertreten: drei in Südindien und Sri Lanka, eine im Süden des Iran (Iranocichla hormuzensis) und sieben bis acht in Israel und Jordanien (Tal des Jordan). Die Buntbarsche Indiens, Madagaskars, Kubas und Hispaniolas gehen auch in Brackwasser. Coptodon guineensis kommt als einzige Buntbarschart von der Mündung des Senegal bis zur Mündung des Kunene im Meer vor.[2]

Einige Arten wurden als Neozoen weit verbreitet. Der Mosambik-Buntbarsch (Oreochromis mossambicus) und mehr noch die Niltilapie (Oreochromis niloticus) wurden aus fischereiwirtschaftlichen Gründen (Aquakultur) in vielen tropischen Länder eingeführt.[3] Ihre Verwilderung in mehreren Ländern hat negative ökologische Auswirkungen, da sie einheimische Arten verdrängen.[4] Ein weiterer Buntbarsch, der Chanchito (Australoheros facetum) aus dem Süden Brasiliens und dem Norden Argentiniens, hat sich auch in Europa, im Süden Portugals und Spaniens, verbreitet[5][6] und kommt inzwischen sogar in einigen deutschen Seen (Baden-Württemberg und Nordrhein-Westfalen) vor.[7]

Die Größe der Buntbarsche reicht von drei Zentimetern (Apistogramma) bis zu 80 Zentimetern (Boulengerochromis, Cichla). Ihre Grundform ist oval, etwas langgestreckt und seitlich abgeflacht, etwa so wie der Rote Buntbarsch in der Taxobox. Angepasst an ihr jeweiliges Habitat kann die Körperform jedoch auch stark von der Grundform abweichen. So sind die zwischen Stelzwurzeln im Orinoko- und Amazonasbecken lebenden Diskusfische und Skalare scheibenförmig, die Skalare weisen zudem stark erhöhte Rücken-, After- und Bauchflossen auf. Andere Buntbarsche sind hechtförmig (Crenicichla) oder langgestreckt (Teleogramma oder Julidochromis, Jagd in Felsspalten). Buntbarsche aus den Livingstonefällen oder den Sandufern des Tanganjikasee ähneln Grundeln. Zwischen diesen Extremen gibt es viele Übergangsformen. Die Maulform ist an die verschiedensten Ernährungstypen angepasst. Sie reicht von tief gespalten bei räuberischen Arten (wie Crenicichla) bis hin zu stark unterständig und auf das Abraspeln von Felsenaufwuchs spezialisiert (bei Labeotropheus).

Im Unterschied zu den meisten anderen Fischen haben Buntbarsche auf jeder Kopfseite nur ein Nasenloch. Ihre Seitenlinie ist unterbrochen, der vordere Teil läuft auf der oberen Körperhälfte parallel zur Rückenkrümmung, der hintere auf der Seitenmitte bis auf den Schwanzflossenstiel. Entlang der Seitenlinie zählt man 20 bis 50 Schuppen, in Ausnahmefällen mehr als 100. In der einzigen Rückenflosse ist deutlich ein hartstrahliger und ein weichstrahliger Teil zu unterscheiden. Sie wird von sieben bis 25 Flossenstacheln und fünf bis 30 Weichstrahlen gestützt. Die Afterflosse hat normalerweise drei Flossenstacheln (bei wenigen Arten auch vier bis neun, bei Etroplus zwölf bis fünfzehn) und vier bis fünfzehn Weichstrahlen, in Ausnahmefällen auch mehr als 30. Die Schwanzflosse ist meist abgerundet oder schließt gerade ab, in vielen Fällen, manchmal nur bei den Männchen, mit filamentartigen Auswüchsen oben und unten. Nur wenige Buntbarsche besitzen eine gegabelte Schwanzflosse.[8]

Die Ernährungsweisen der Buntbarsche sind sehr vielfältig. So gibt es generalisierte Räuber, Planktonfresser, Aufwuchsfresser, Pflanzenfresser und Larvenfresser. In den Seen des Ostafrikanischen Grabenbruches ist die Spezialisierung bezüglich der Ernährung besonders gut zu sehen und erforscht worden.

Viele der Buntbarsche sind primär Pflanzenfresser, die sich von Algen (z. B. Petrochromis) und Pflanzen (z. B. Etroplus suratensis) ernähren. Kleine Tiere, wie Wirbellose, machen nur einen geringen Teil ihrer Nahrung aus. Detritivore, zu welchen die Gattungen Oreochromis, Sarotherodon und Tilapia gehören, fressen verschiedenes organisches Material.

Räuberisch lebende Buntbarsche fressen wenig bis gar kein Pflanzenmaterial. Eingeteilt werden die Räuber in Spezialisten und in Generalisten, die Jagd auf kleine Tiere wie Fische und Insektenlarven machen. Trematocranus ist zum Beispiel ein auf Schnecken spezialisierter Buntbarsch, während sich Pungu maclareni von Schwämmen ernährt. Ein Teil der Buntbarsche ernährt sich ganz oder teilweise von anderen Fischen. Hechtbuntbarsche (Crenicichla) sind heimliche Räuber, die sich aus einem Versteck heraus auf vorbeischwimmende Fische stürzen, während Rhamphochromis-Arten ihre Beute im offenen Gewässer verfolgen.[9] Einige Gattungen der Buntbarsche (z. B. Caprichromis) ernähren sich von den Eiern oder Juvenilen anderer Spezies.[10][11][12][13] Dafür rammen die Räuber teilweise die Köpfe von Maulbrütern, die dadurch gezwungen sind, ihre Jungtiere auszuspucken. Zu den Buntbarschen mit außergewöhnlicher Ernährungsstrategie gehören Corematodus, Docimodus, Plecodus, Perissodus und Genyochromis mento, welche sich von Schuppen und Flossen anderer Fische ernähren. Dieses Verhalten ist als Lepidophagie bekannt. Eine ebenfalls spezielle Ernährungsstrategie zeigen Nimbochromis und Parachromis, die sich tot stellen und regungslos daliegen, bis Beute heranschwimmt und geschnappt werden kann.[14][15][16]

An die verschiedenen Ernährungsstrategien angepasst sind die unterschiedlichen Schlundzähne. Mit dem Kiefer wird die Nahrung aufgenommen und festgehalten, während die Schlundzähne als Kauwerkzeug dienen. Durch die verschiedenen Ernährungsstrategien ist es den Buntbarschen möglich, unterschiedliche Habitate zu besiedeln.

Unter anderem könnte die strukturelle Diversität des unteren Schlundkiefers ein Grund für das Auftreten der vielen Buntbarscharten sein. Die konvergente Evolution fand im zeitlichen Verlauf der Radiation statt, synchron zu den unterschiedlichen trophischen Nischen.[17]

Der Schlundkieferapparat besteht aus zwei oberen und einer einzelnen unteren Platte, welche alle eine Bezahnung aufweisen, die sich in Größe und Typ unterscheidet.[18] Die Struktur des unteren Schlundkiefers ist oft mit der Ernährungsart der Spezies assoziiert.[19]

Um Schalenweichtiere knacken zu können, muss eine erhebliche Druckkraft erzeugt werden, weshalb die Buntbarsche, welche sich von Schalenweichtieren ernähren (z. B. der Hechtbuntbarsch Crenicichla minuano), molariforme Zähne und einen verstärkten Schlundkieferknochen haben. Um schalenlose Beutetiere packen und zerbeißen zu können, benötigen die Räuber konische, zurückgebogene Zähne.[20] Bei den herbivoren Buntbarschen wurden ebenfalls strukturelle Unterschiede der Schlundkieferbezahnung gefunden. Buntbarsche, die auf Algen spezialisiert sind (z. B. Pseudotropheus), weisen eher kleine konische Zähne auf. Arten, die sich von Hülsen oder Samen ernähren, benötigen große konische Zähne für das Zerbeißen ihrer Nahrung.[21]

Zusätzlich zur Bezahnung weist auch die Form des unteren Schlundkieferknochens eine große Variation auf.

Die männlichen Fische der Art Oreochromis mossambicus reagieren in der Regel äußerst aggressiv, wenn Artgenossen in ihr Revier eindringen. Im stets folgenden Revierkampf gegen die Eindringlinge steigt bei ihnen die Blutkonzentration von Sexualhormonen deutlich an. Die Konzentration dieser Androgene erhöht sich jedoch nicht nur bei den Kämpfern, sondern sogar bei anderen dem Kampf zuschauenden Männchen. Durch verschiedene Experimente haben portugiesische Wissenschaftler um Rui Oliviera von der Hochschule für angewandte Psychologie in Lissabon (Portugal) herausgefunden, dass die Revierkämpfer vor allem dann ihre Hormonproduktion steigern, wenn sie in einem Kampf auf Grund der geringeren Größe oder einer erkennbaren Verletzung des Rivalen gute Aussichten auf einen Sieg haben. Können sie jedoch ihre Erfolgsaussichten nicht klar einschätzen, verändert sich bei ihnen auch nicht die Hormonkonzentration.

Die meisten Arten zeigen ein für Fische recht ausgeprägtes Brutpflegeverhalten sowohl für die Eier als auch für die Larven. Man unterscheidet Substratlaicher (mit Offenlaichern und Höhlenlaichern) und Maulbrüter. Buntbarsche beschützen die Eier, indem sie Feinde von Gelege und Larven fernhalten und die Eier durch „Ablutschen“ und Fächeln reinigen. Je umfassender und somit erfolgversprechender die Brutpflege ist, desto weniger Eier werden gelegt. Häufig dauert sie an, bis die Jungtiere mehrere Wochen alt sind. Bei einigen der im Tanganjikasee vorkommenden Arten sind sogar die älteren Geschwister an der Aufzucht der jüngeren beteiligt.

Je nachdem, in welcher Form sich die Elternteile an der Brutpflege beteiligen, unterscheidet man folgende Familienformen:[22][23]

Die Buntbarsche wurden traditionell mit einigen Familien von Meeresfischen in die Unterordnung der Lippfischartigen (Labroidei) innerhalb der Ordnung der Barschartigen (Perciformes) gestellt. Die Verwandtschaft der Familien wird durch die Anatomie der Schlund- und Kiemenregion gestützt.

DNA-Sequenzierungen lassen aber keine Verwandtschaft zwischen Lippfischen, Papageifischen und Odaciden auf der einen und Buntbarschen, Brandungsbarschen und Riffbarschen auf der anderen Seite erkennen. Die ähnliche Schädelanatomie muss unabhängig voneinander mindestens zwei Mal entstanden sein.[24]

Für die Buntbarsche, die Ährenfischverwandten, die Brandungsbarsche und Riffbarsche und einige andere mit ihnen verwandte Taxa wird deshalb eine neue systematische Gruppe innerhalb der Barschverwandten, die Ovalentaria, vorgeschlagen. Als Schwestergruppe der Buntbarsche wurde überraschenderweise Pholidichthys ermittelt, eine nur zwei Arten umfassende Gattung und Familie von aalartig langgestreckten Meeresfischen, die mit den Buntbarschen das einzelne Nasenloch auf jeder Kopfseite, ein paariges Haftorgan auf der Kopfoberseite der Larven und die intensive Brutpflege teilen.[25] Als neue Ordnung für die Buntbarsche und Pholidichthys wird in aktuellen Systematiken die nach den Cichliden benannte Ordnung Cichliformes verwendet.[26][27]

Die Buntbarsche werden in vier Unterfamilien und in eine Reihe von Triben eingeteilt. An der Basis des Stammbaums stehen die in Indien und Madagaskar lebenden Etroplinae und die madagassischen Ptychochrominae. Die weit mehr als 1200 Arten der afrikanischen Buntbarsche gehören alle zur Unterfamilie Pseudocrenilabrinae, die süd- und mittelamerikanischen zur Unterfamilie Cichlinae.[28]

Folgendes Kladogramm gibt die wahrscheinlichen verwandtschaftlichen Verhältnisse wieder:

CichlidaeEtroplinae (Indien und Madagaskar)

Ptychochrominae (Madagaskar)

Pseudocrenilabrinae (Afrika & Vorderasien)

Cichlinae (Süd- und Mittelamerika)

Es gibt etwa 1700 Arten aus über 230 Gattungen:

GattungenSympatrische Artbildung (das Entstehen neuer Arten im Gebiet der Ursprungsart(en)) findet sich bei Buntbarschen in isolierten Seen, z. B. in Kraterseen in Nicaragua (Apoyo, Masay)[29] und im Barombi Mbo[30] und Bermin-Kratersee (Kamerun).[31] Die Buntbarscharten dieser Seen stammen von jeweils einer eingewanderten Art ab, unterscheiden sich aber heute deutlich in ihrer Morphologie und ökologischen Nische. Eine allopatrische Artbildung kann in diesen kleinen Kraterseen ausgeschlossen werden.

Molekulare Daten sprechen für eine Entstehung der Familie der Cichliden vor 97 bis 78 Millionen Jahren. Die indisch-madegassischen Etroplinae sind etwa 87 bis 66 Millionen Jahre alt, die rein madegassischen Ptychochrominae 78 bis 60 und die Neuweltcichliden und die Unterfamilie Pseudocrenilabrinae trennten sich vor 70 bis 55 Millionen Jahren voneinander. Das bedeutet das die Aufspaltung in die vier Unterfamilien lange nach dem Auseinanderbrechen Gondwanas stattfand. Entweder verbreiteten sich die heute fast ausschließlich im Süßwasser und nur mit wenigen Arten auch im Brackwasser vorkommenden Buntbarsche über Meere und Meeresarme oder es gab einen unbekannten marinen Vorfahren, dessen Nachfahren nacheinander unabhängig voneinander die Kontinente besiedelte. Da die im Meere lebende Gattung Pholidichthys der engste Verwandte der Buntbarsche ist, könnte es sein, dass eine hohe Salztoleranz in der frühen Evolution der Buntbarsche noch weit verbreitet war.[32]

Der große Artenschwarm der Ostafrikanischen Großen Seen entstand vor etwa 9,5 bis 6,9 Millionen Jahren, der jüngste gemeinsame Vorfahre der Buntbarsche des Victoria- und des Malawisees lebte vor 3,1 bis 1,7 Millionen Jahren. Etwas jünger ist der Artenschwarm im kamerunischen See Barombi Mbo (2,3 bis 1,4 Millionen Jahre).[33]

Wie Fossilien von fünf Buntbarscharten (Gattung Mahengechromis) aus einem ehemaligen kleinen Kratersee aus dem Eozän (46,3–45,7 Mio. Jahre) von Tansania zeigen, bildete die Familie auch in der Vergangenheit Artenschwärme.[34]

In der Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts wurden die Seenkette im Ostafrikanischen Grabenbruch und der Viktoriasee von Aquaristen entdeckt. Die enorme Artenzahl endemischer Arten in diesen Seen führte rasch zu großer Beliebtheit in der Aquaristik. Besonders Arten aus dem Tanganjika-See und dem Malawi-See (Mbunas und Utakas, auch Nicht-Mbunas genannt) wurden nach Europa und Amerika ausgeführt.

Gehalten werden Buntbarsche am besten in reinen Cichlidenbecken, zum Beispiel einem Biotop-Aquarium. Besonders problematisch ist, dass sich viele der Arten an den im Aquarium gepflegten Pflanzen vergreifen. Aquarianern, die diese Arten halten, stehen nur eine begrenzte Anzahl von Pflanzenarten zur Verfügung. Dazu zählt unter anderem das Zwergspeerblatt.

Siehe auch: Deutsche Cichliden-Gesellschaft

Buntbarsche (Cichlidae) oder Cichliden sind eine Familie der Knochenfische aus der Gruppe der Barschverwandten (Percomorphaceae). Nach den Karpfenfischen (Cyprinidae) und den Grundeln (Gobiidae) bilden die Buntbarsche mit etwa 1700 beschriebenen Arten die drittgrößte Fisch-Familie. Viele Arten sind wegen ihres farbenprächtigen Äußeren, des komplexen Verhaltensspektrums und der einfachen Pflege beliebte Aquarienfische, einige große Arten sind wichtige Speisefische.

In der Evolutionsbiologie hat die Untersuchung der Cichliden wesentlich zum Verständnis der Mechanismen der Artbildung beigetragen. Die Artenschwärme der Buntbarsche im Victoriasee und ihrer Verwandten in den benachbarten Afrikanischen Großen Seen können als Modell für eine relativ rasche Artenentwicklung betrachtet werden. Zudem sind Buntbarsche bedeutende Forschungsobjekte in der Verhaltensbiologie.

Dia Buntschroutzen oder aa Buntbarsch oder Cichliden (Cichlidae) sand a Famij vo da Ordnung vo dia Schroutzner (Perciformes). Cichliden sand ouft seer formenreich (1.700 Oarten).

A Pour Oarten sand wichtige Speisefiesch, onnerne sand ois Aquariënfiesch beliabb. A' da Evoluzionsforschung houd d' Untersuaching vo dia Schroutzner intressante Erkenntniss za dia Mechanismen vo da Oartenbijdung broucht. D' Evoluzion vo d' Buntschroutzner vam Viktoriasee und eanerne Vawondten in dia benouchbaschten Seen, stejd heid a Modej fiaa relatiav rosche Oartenenwickling dour.

Dia Vurfourn vo d' Buntbarsch sand ursprynglich aus'm Meer kemmer und sand eascht nouchernt zan Leem an Siasswousser iwagonger.

Buntschroutzner bewonernd mid eppa 1.700 Oarten an greessern Toae vam tropischen Afrika und mid eppa 550 Oarten s Amerika sidlich vam 30 Grad nerdlicher Breaden. 17 Oarten leemd auf Madagaskar, se sand stourch in eanerm Bstond gfärdescht. In Asien sand dia Buntschroutzner mid netta ejf bis zwejf Oarten vadreeden (droi in Indiën, oane an Iran: Iranocichla hormuzensis) und siem bis oucht in Israel und Jordanien (Jordantoi).

Alloah in d' ostafrikanischn Seen (Malawisee, Tanganjikasee) leemd 350 Oarten und im Viktoriasee kemmernd 250 bis 350 Oarten vir.

Dia Buntschroutzen oder aa Buntbarsch oder Cichliden (Cichlidae) sand a Famij vo da Ordnung vo dia Schroutzner (Perciformes). Cichliden sand ouft seer formenreich (1.700 Oarten).

A Pour Oarten sand wichtige Speisefiesch, onnerne sand ois Aquariënfiesch beliabb. A' da Evoluzionsforschung houd d' Untersuaching vo dia Schroutzner intressante Erkenntniss za dia Mechanismen vo da Oartenbijdung broucht. D' Evoluzion vo d' Buntschroutzner vam Viktoriasee und eanerne Vawondten in dia benouchbaschten Seen, stejd heid a Modej fiaa relatiav rosche Oartenenwickling dour.

Cichlids are fish frae the faimily Cichlidae in the order Cichliformes.

La familha dels Ciclids aparten al sosòrdre dels Labroidei, que compta tanben de familhas coma los Pomacentrids (Peis palhassa) o los Escarids (Peis papagai).

Aquesta familha compòrta mai de 200 genres e entre 1 600[1] e 1 800 espècias, repartidas principalament en Africa, en America centrala, America del Sud, Texas (una espècia), Israèl, Madagascar, Siria, Iran, Sri Lanka e sus las còstas sud de las Índias. Fòrça espècias son importadas e de còps elevadas en Euròpa dins d'aqüaris, en rason de lor coloracion viva e de lors comportaments de còps evoluats.

Se compta demest sos membres los mai celèbres l'escalar, l'òscar o encara lo discus.

La desaparicion massiva de las 200 espècias diferentas de ciclids del lac Victòria, espècias que son diversificadas dempuèi 12 000 ans, es una illustracion de las menaças que pesan sus la biodiversitat.

Lo comportament evoluat dels ciclids fascina los aqüariofils. Mesa a part la facultat d'aprendissatge que mòstran en captivitat (en particular per l'oscar, sovent considerat coma l'equivalent aqüatic del can), se pòt citar lor mòde de reproduccion : quand los uòus benefician pas d'una incubacion bucala, mairala, pairala o biparentala, son gelosament susvelhats pels parents, qu'esitan pas a velhar sus lor progenitura longtemps aprèp l'espelison, en ofrent, per certanas espècias, lor boca coma proteccion e mejan de locomocion a la rabalha.

L'òscar (Astronotus ocellatus) es un dels ciclids los mai populars en aqüariofilia.

(Cichla ocellaris) es estat introdusit intencionalament en Florida coma peis de pesca esportiva.

Oreochromis niloticus es elevat e consomat dins fòrça partidas del mond

L'escalar (Pterophyllum scalare) es estat elevat longtemps pel comèrci aqüariofil.

Lo dimorfisme sexual es visible en çò dels ciclids. Un mascle (davant) e una femèla (a l'arrièr) Maylandia lombardoi

Un coble de ramirezi (Mikrogeophagus ramirezi), mascle davant, femèla darrièr. Fòrça ciclids fòrman de cobles per se reprodusir.

Un discus (Symphysodon) susvelha sos uòus. La proteccion dels uòus es una de las caracteristicas dels ciclids.

Lo Lac Malawi en Africa de l'Oèst abriga fòrça espècias de ciclids dont (Nimbochromis livingstonii)

Un ciclid del genreLamprologus originari del Lac Tanganyika en Africa de l'Èst

Lo ciclid del Texàs (Herichthys cyanoguttatus) es lo sol ciclid indigèna dels Estats Units

Pelvicachromis pulcher es un ciclid originari de l'Africa de L'Oèst, es un ciclid nan.

Nannacara adoketa, es un ciclid nan originari de Brasil.

La familha dels Ciclids aparten al sosòrdre dels Labroidei, que compta tanben de familhas coma los Pomacentrids (Peis palhassa) o los Escarids (Peis papagai).

Aquesta familha compòrta mai de 200 genres e entre 1 600 e 1 800 espècias, repartidas principalament en Africa, en America centrala, America del Sud, Texas (una espècia), Israèl, Madagascar, Siria, Iran, Sri Lanka e sus las còstas sud de las Índias. Fòrça espècias son importadas e de còps elevadas en Euròpa dins d'aqüaris, en rason de lor coloracion viva e de lors comportaments de còps evoluats.

Se compta demest sos membres los mai celèbres l'escalar, l'òscar o encara lo discus.

La desaparicion massiva de las 200 espècias diferentas de ciclids del lac Victòria, espècias que son diversificadas dempuèi 12 000 ans, es una illustracion de las menaças que pesan sus la biodiversitat.

Ciklidi su ribe iz velike i raznolike porodice Cichlidae, u koju spada otprilike 1,300 opisanih vrsta, a zbog velikog broja neotkrivenih vrsta, pretpostavlja se da će konačan broj vrsta ove porodice doseći 1,900. [1] Ciklidi su ribe koje se značajno razlikuju u obliku, boji, veličini, načinu života i ponašanju.

Veličina predstavnika ove porodice se kreće od 2,5 centimetra do 1 metra, dok oblici tijela variraju od snažno bočno spljoštenih do valjkastih. Oblik tijela zavisi od okruženja u kojem se nalaze: bočno spljoštene ribe poput onih iz roda Pterophyllum su prilagođene skrivanju među gustim vodenim biljem, dok je oblik tijela riba iz roda Julidochromis specijaliziran za uvlačenje u uske rupe u kamenjima. Mužjaci su veći i intenzivnije obojeni, veoma teritorijalni i često agresivni prema ribama svoje i druge vrste. Živopisno obojene vrste postaju sve popularnije akvarijumske ribe, dok su rjeđe one neuglednih boja. Pojedine vrste, poput tilapije, su važne ribe u prehrani.

Ciklidi u prirodi naseljavaju tropske vode Južne Azije, Afrike, Južne i Centralne Amerike. Najčešće se nalaze u slatkim, bilo tekućim ili stajaćim vodama, mada se neke vrste (od kojih su najznačajnije vrste rodova Etroplus i Sarotherodon) mogu naći u bočatnim i slanim vodama. [2]

Ishrana ciklida varira jednako kao i oni sami. Postoje vrste koje su primarno herbivori, te se hrane algama i mehkim dijelovima viših biljaka, a u ishranu samo povremeno uključuju manje beskičmenjake. Ostale vrste su sposobni predatori - karnivori čiji se plijen kreće od puževa, larvi insekata, spužvi pa do ostalih riba. Manji broj vrsta spada u detritovore, hraneći se trulećom organskom materijom.

Pojedine ribe ove porodice su izrazito monogamne, dok ostale formiraju hareme koji se sastoje od jednoga mužjaka i više ženki. Svi predstavnici ove porodice iskazuju izraženu roditeljsku brigu za jaja i mlađ. Ikru ili mlađ čuvaju oba ili samo jedan roditelj, zavisno od vrste. Roditelji vrsta koje ikru polažu na otvorenom (lišću biljaka, kamenjima ili podlozi) aerišu vodu oko ikre, odstranjuju pljesnjivu i neoplođenu ikru, te je agresivno čuvaju od predatora. Drugi oblik roditeljske brige je čuvanje ikre i mlađi u ustima, a susreće se kod riba iz roda Haplochromis. Ženke ovih vrsta ikru odmah po oplođenju smještaju u usta i tu je čuvaju tokom inkubacije i nakon izlijeganja mlađi. Za svo ovo vrijeme ženke ne jedu i vrijeme provode skrivene od ostalih riba, koje ih nekad pokušavaju natjerati da izbace mlađ iz usta. Iako su uglavnom ženke one koje mlađ čuvaju u ustima, to mogu biti i mužjaci, te rjeđe oba roditelja. [3] [4] [5] Neke vrste, poput diskusa, poznate su po sposobnosti da mlađ hrane svojim kožnim izlučevinama. [3]

Spisak iz 2006. godine uključivao je 220 rodova: [1]

Prema izvještaju iz 2007. godine, 156 vrsta ciklida nalazi se na spisku ranjivih, četrdeset na spisku ugroženih, a 69 na spisku kritično ugroženih vrsta. Od 1990. u divljini je izumrlo 45 vrsta ciklida, među kojima je najviše ustonoša. [6]

Ciklidi su ribe iz velike i raznolike porodice Cichlidae, u koju spada otprilike 1,300 opisanih vrsta, a zbog velikog broja neotkrivenih vrsta, pretpostavlja se da će konačan broj vrsta ove porodice doseći 1,900. Ciklidi su ribe koje se značajno razlikuju u obliku, boji, veličini, načinu života i ponašanju.

Veličina predstavnika ove porodice se kreće od 2,5 centimetra do 1 metra, dok oblici tijela variraju od snažno bočno spljoštenih do valjkastih. Oblik tijela zavisi od okruženja u kojem se nalaze: bočno spljoštene ribe poput onih iz roda Pterophyllum su prilagođene skrivanju među gustim vodenim biljem, dok je oblik tijela riba iz roda Julidochromis specijaliziran za uvlačenje u uske rupe u kamenjima. Mužjaci su veći i intenzivnije obojeni, veoma teritorijalni i često agresivni prema ribama svoje i druge vrste. Živopisno obojene vrste postaju sve popularnije akvarijumske ribe, dok su rjeđe one neuglednih boja. Pojedine vrste, poput tilapije, su važne ribe u prehrani.

Ciklidi u prirodi naseljavaju tropske vode Južne Azije, Afrike, Južne i Centralne Amerike. Najčešće se nalaze u slatkim, bilo tekućim ili stajaćim vodama, mada se neke vrste (od kojih su najznačajnije vrste rodova Etroplus i Sarotherodon) mogu naći u bočatnim i slanim vodama.

Ishrana ciklida varira jednako kao i oni sami. Postoje vrste koje su primarno herbivori, te se hrane algama i mehkim dijelovima viših biljaka, a u ishranu samo povremeno uključuju manje beskičmenjake. Ostale vrste su sposobni predatori - karnivori čiji se plijen kreće od puževa, larvi insekata, spužvi pa do ostalih riba. Manji broj vrsta spada u detritovore, hraneći se trulećom organskom materijom.

Pojedine ribe ove porodice su izrazito monogamne, dok ostale formiraju hareme koji se sastoje od jednoga mužjaka i više ženki. Svi predstavnici ove porodice iskazuju izraženu roditeljsku brigu za jaja i mlađ. Ikru ili mlađ čuvaju oba ili samo jedan roditelj, zavisno od vrste. Roditelji vrsta koje ikru polažu na otvorenom (lišću biljaka, kamenjima ili podlozi) aerišu vodu oko ikre, odstranjuju pljesnjivu i neoplođenu ikru, te je agresivno čuvaju od predatora. Drugi oblik roditeljske brige je čuvanje ikre i mlađi u ustima, a susreće se kod riba iz roda Haplochromis. Ženke ovih vrsta ikru odmah po oplođenju smještaju u usta i tu je čuvaju tokom inkubacije i nakon izlijeganja mlađi. Za svo ovo vrijeme ženke ne jedu i vrijeme provode skrivene od ostalih riba, koje ih nekad pokušavaju natjerati da izbace mlađ iz usta. Iako su uglavnom ženke one koje mlađ čuvaju u ustima, to mogu biti i mužjaci, te rjeđe oba roditelja. Neke vrste, poput diskusa, poznate su po sposobnosti da mlađ hrane svojim kožnim izlučevinama.

Οι Κιχλίδες (Cichlidae) αποτελούν μεγάλη οικογένεια ψαριών των γλυκών νερών κυρίως των τροπικών χωρών που μοιάζουν πολύ με τις πέρκες. Ζουν σε λίμνες και ποταμούς της Αφρικής, της Μέσης Ανατολής, της Ινδίας και της τροπικής Αμερικής. Οι Κιχλίδες είναι ψάρια σαρκοφάγα ή φυτοφάγα και μερικά είδη αυτών παρουσιάζουν κατά την αναπαραγωγή εμφανείς σεξουαλικές διαφορές, (αρσενικά - θηλυκά), που εξαφανίζονται στη συνέχεια.

Κάποια είδη του γένους «Τιλάπια»[13] (Tilapia)[14] αποτελούν σημαντικό είδος ιχθυοτροφίας για τον εμπλουτισμό των αφρικανικών λιμνών και κάλυψη αναγκών της τοπικής διατροφής των παρόχθιων αφρικανικών λαών και όχι μόνο.

Οι τιλαπίες αυξάνονται σχετικά γρήγορα, πολλαπλασιάζονται σε ηλικία 10 – 11 μηνών όπου το μήκος τους φθάνει τα 20 εκ. και το βάρος τους τα 150 γρ. Χαρακτηριστικά είδη του γένους αυτού είναι η «Τιλάπια η νειλοτική», (Tilapia nilotica), που απαντά στον Νείλο, η «Τιλάπια η γαλιλαία», (Tilapia galilea), που απαντά στη Μέση Ανατολή, και η «Τιλάπια η μακρόχειρ» (Tilapia macrochir), που όλα τρέφονται με μικρότερα ψάρια, ενώ τα θηλυκά αυτών επωάζουν τ΄ αυγά τους μέσα στο στόμα τους. Αντίθετα τα είδη «Τιλάπια η ζίλλειος» (Tilapia zilli), και «Τιλάπια η μελανόπλευρος», (Tilapia melanopleura), είναι χορτοφάγα και τα θηλυκά δεν επωάζουν τ΄ αυγά τους με τον παραπάνω τρόπο.

Στην οικογένεια των Κιχλίδων ανήκουν και πολλά είδη περιζήτητα για οικιακά ενυδρεία, όπως το είδος «Πτερόφυλλον το σκαλικόν»[15], (Pterophyllum scalare) που φέρει στο σώμα του τρεις χαρακτηριστικές κάθετες μαύρες ραβδώσεις, (μία στο κεφάλι, μία περί τα στηθικά πτερύγια και μία μεγάλη που καταλήγει στις πίσω άκρες του ραχιαίου και κοιλιακού πτερυγίων), κάνοντάς το πολύ διακοσμητικό ψάρι.

Άλλα γένη της οικογένειας των Κιχλιδών είναι ο «Γεωφάγος», (Geophagus), ο «Ήρως», (Heros), η «Κίχλη», (Cichla), ο «Λαμπρολόγος» , (Lamprologus), η «Παρατιλάπια», (Paratilapia), κ.ά.

Οι Κιχλίδες ανήκουν στην υπόταξη των Περκοειδών.

Οι Κιχλίδες (Cichlidae) αποτελούν μεγάλη οικογένεια ψαριών των γλυκών νερών κυρίως των τροπικών χωρών που μοιάζουν πολύ με τις πέρκες. Ζουν σε λίμνες και ποταμούς της Αφρικής, της Μέσης Ανατολής, της Ινδίας και της τροπικής Αμερικής. Οι Κιχλίδες είναι ψάρια σαρκοφάγα ή φυτοφάγα και μερικά είδη αυτών παρουσιάζουν κατά την αναπαραγωγή εμφανείς σεξουαλικές διαφορές, (αρσενικά - θηλυκά), που εξαφανίζονται στη συνέχεια.

Κάποια είδη του γένους «Τιλάπια» (Tilapia) αποτελούν σημαντικό είδος ιχθυοτροφίας για τον εμπλουτισμό των αφρικανικών λιμνών και κάλυψη αναγκών της τοπικής διατροφής των παρόχθιων αφρικανικών λαών και όχι μόνο.

Οι τιλαπίες αυξάνονται σχετικά γρήγορα, πολλαπλασιάζονται σε ηλικία 10 – 11 μηνών όπου το μήκος τους φθάνει τα 20 εκ. και το βάρος τους τα 150 γρ. Χαρακτηριστικά είδη του γένους αυτού είναι η «Τιλάπια η νειλοτική», (Tilapia nilotica), που απαντά στον Νείλο, η «Τιλάπια η γαλιλαία», (Tilapia galilea), που απαντά στη Μέση Ανατολή, και η «Τιλάπια η μακρόχειρ» (Tilapia macrochir), που όλα τρέφονται με μικρότερα ψάρια, ενώ τα θηλυκά αυτών επωάζουν τ΄ αυγά τους μέσα στο στόμα τους. Αντίθετα τα είδη «Τιλάπια η ζίλλειος» (Tilapia zilli), και «Τιλάπια η μελανόπλευρος», (Tilapia melanopleura), είναι χορτοφάγα και τα θηλυκά δεν επωάζουν τ΄ αυγά τους με τον παραπάνω τρόπο.

Στην οικογένεια των Κιχλίδων ανήκουν και πολλά είδη περιζήτητα για οικιακά ενυδρεία, όπως το είδος «Πτερόφυλλον το σκαλικόν», (Pterophyllum scalare) που φέρει στο σώμα του τρεις χαρακτηριστικές κάθετες μαύρες ραβδώσεις, (μία στο κεφάλι, μία περί τα στηθικά πτερύγια και μία μεγάλη που καταλήγει στις πίσω άκρες του ραχιαίου και κοιλιακού πτερυγίων), κάνοντάς το πολύ διακοσμητικό ψάρι.

Άλλα γένη της οικογένειας των Κιχλιδών είναι ο «Γεωφάγος», (Geophagus), ο «Ήρως», (Heros), η «Κίχλη», (Cichla), ο «Λαμπρολόγος» , (Lamprologus), η «Παρατιλάπια», (Paratilapia), κ.ά.

सिक्लिड (Cichlid) पर्सिफ़ोर्मेज़ गण के सिक्लिडाए कुल की हड्डीदार मछलियाँ होती हैं। वे लैब्रोइडेइ (Labroidei) नामक उपगण की सदस्य होती हैं जिसमें कुछ अन्य मछली कुल भी शामिल हैं। सिक्लिडों का कुल विस्तृत और विविध है। वर्तमान में इस कुल में १,६५० से अधिक जातियाँ मिल चुकी हैं और हर वर्ष यह गिनती बढ़ती जाती है। सम्भव है कि इस कुल में २०००-३००० जातियाँ हों। मछली पालन के शौकीन अक्सर सिक्लिडों को अपने घरों में पालते हैं।[1]

सिक्लिड (Cichlid) पर्सिफ़ोर्मेज़ गण के सिक्लिडाए कुल की हड्डीदार मछलियाँ होती हैं। वे लैब्रोइडेइ (Labroidei) नामक उपगण की सदस्य होती हैं जिसमें कुछ अन्य मछली कुल भी शामिल हैं। सिक्लिडों का कुल विस्तृत और विविध है। वर्तमान में इस कुल में १,६५० से अधिक जातियाँ मिल चुकी हैं और हर वर्ष यह गिनती बढ़ती जाती है। सम्भव है कि इस कुल में २०००-३००० जातियाँ हों। मछली पालन के शौकीन अक्सर सिक्लिडों को अपने घरों में पालते हैं।

Cichlids /ˈsɪklɪdz/[a] are fish from the family Cichlidae in the order Cichliformes. Cichlids were traditionally classed in a suborder, the Labroidei, along with the wrasses (Labridae), in the order Perciformes,[1] but molecular studies have contradicted this grouping.[2] On the basis of fossil evidence, it first appeared in Tanzania during the Eocene epoch, about 46–45 million years ago.[3][4] The closest living relative of cichlids is probably the convict blenny, and both families are classified in the 5th edition of Fishes of the World as the two families in the Cichliformes, part of the subseries Ovalentaria.[5] This family is large, diverse, and widely dispersed. At least 1,650 species have been scientifically described,[6] making it one of the largest vertebrate families. New species are discovered annually, and many species remain undescribed. The actual number of species is therefore unknown, with estimates varying between 2,000 and 3,000.[7]