Page snapshot: An introduction to Australo-Pacific kingfishers (genus Todiramphus), including their evolution, behavior, distribution, and threats.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction; Evolution; Behavior; Distribution; Threats; Resources.

Credits: Funded by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Updates: Page last updated March 12, 2024.

Image above: A rufous-lored kingfisher (Todiramphus winchelli), Philippines. Photo by Forest Botial-Jarvis (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

Introduction

The Australo-Pacific kingfishers are a group of kingfishers in the genus Todiramphus that inhabit parts of Asia and Oceania, from the Red Sea region in eastern Africa and the Middle East to islands far out in the Pacific Ocean. Currently, scientists recognize about 30 species of Australo-Pacific kingfishers, although more probably exist. Most of these kingfishers live on islands. Some are single-island endemics (meaning that they only live on one island). Only three species are migratory.

Australo-Pacific kingfishers vary somewhat in size, from the small New Britain kingfisher (Todiramphus albonotatus, about 16 to 18 cm or 6 to 7 inches long) to the much larger Beach Kingfisher (Todiramphus saurophagus) and Sombre kingfisher (Todiramphus funebris), which are nearly twice as long. Their plumage includes colors ranging from white to blue-green to rufous (reddish) and black. They inhabit woodlands, and one of the greatest threats to Australo-Pacific kingfishers is habitat loss.

Sombre kingfisher (Todiramphus funebris), Halmahera, Indonesia. Photo by Bill Bacon (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Cinnamon-banded kingfisher (Todiramphus australasia), Tanimbar Islands Regency, Indonesia. Photo by James Eaton (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license, image resized).

Evolution

The genus Todiramphus is relatively young. The most recent common ancestor of all living Australo-Pacific kingfishers is thought to have lived in the Miocene epoch, about 10 million years ago. At this time, the Earth was similar to that of the present day. The continents were in similar positions and Antarctica was covered by an ice sheet. Global temperature, however, was warmer.

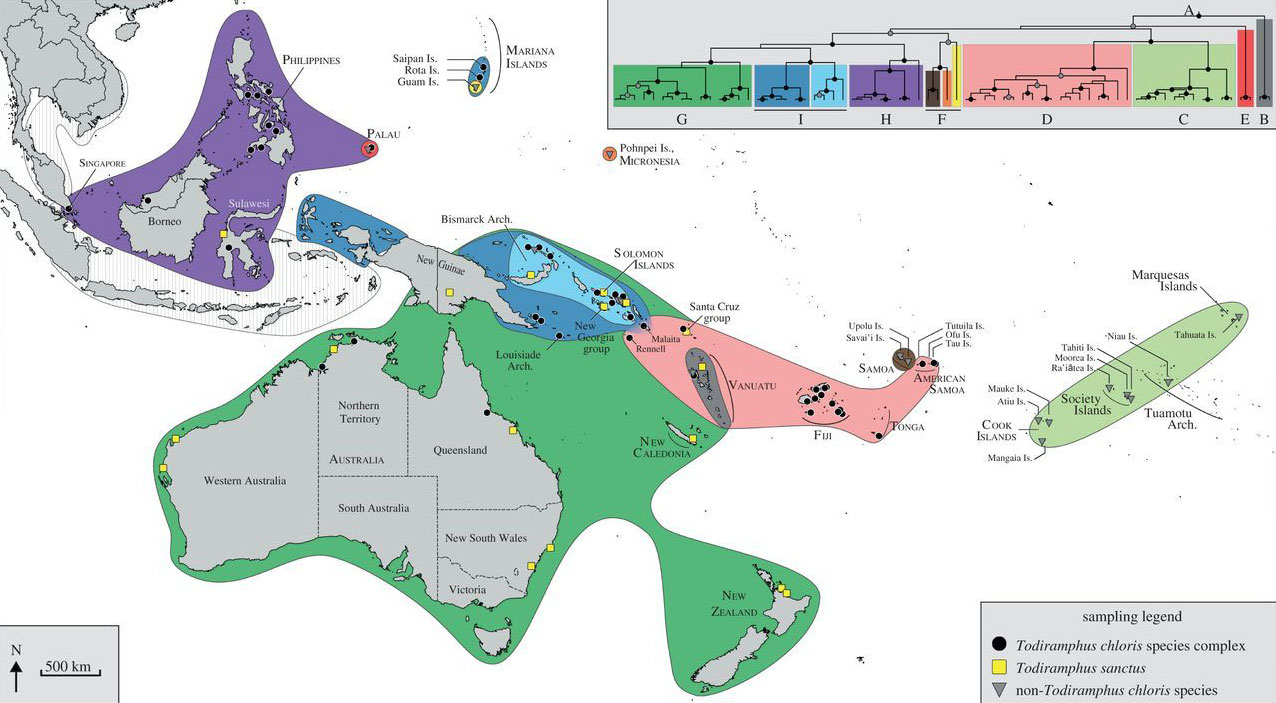

The Australo-Pacific kingfishers diversified very rapidly on their island habitats. In fact, because islands provide patches of habitat separated by water, they may have helped drive the radiation of Australo-Pacific kingfishers into multiple species very rapidly. This radiation of species, called a geographic radiation, is of special interest to evolutionary biologists (scientists that study the process of evolution).

A figure from a study of the collared kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris) species complex. The tree of relationships in the upper right shows the relationships among different birds whose DNA was sampled and analyzed. The map is shaded to show the distributions of different groups of birds that are color-coded on the tree. Source: Figure 1 from Andersen et al. (2015) Royal Society Open Science (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Behavior

Feeding

Australo-Pacific kingfishers, like other kingfishers, are carnivorous. While some species eat fish as part of their diet, many feed mostly or even entirely on other types of animals. These include insects, crustaceans (crabs, shrimp), frogs, lizards, snakes, spiders, and even mice and the eggs and nestlings of other birds.

New Zealand kingfisher (Todiramphus sanctus subspecies vagans) with a crab, Owaka, New Zealand. Photo by Stewart Armstrong (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

New Zealand kingfisher (Todiramphus sanctus subspecies vagans) with a South African mantis (Miomantis caffra), Aukland, New Zealand. Photo by Jacqui Geux (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

Nesting

Kingfishers generally nest in burrows, and some Australo-Pacific kingfishers also excavate burrows in the earth to lay their eggs and raise their young. Another common nesting site for Australo-Pacific kingfishers is a hole carved into the nest of tree-dwelling termites. Australo-Pacific kingfisher nests may also be found in cavities in tree trunks, in epiphytic ferns (ferns that grow on trees), in rotten trees, or in soil among exposed tree roots. Australo-Pacific kingfishers usually nest in pairs, but sometimes three birds nest together or one or several birds may assist the main pair.

Red-backed kingfisher (Todiramphus pyrrhopygius) at the entrace to a burrow dug into an earthen bank, New South Wales, Australia. Photo by waterworks90 (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license, image resized).

Sacred kingfisher (Todiramphus sanctus) at the entrace to a nesting hole made in a tree-dwelling termite nest, Queensland, Australia. Photo by Scott Warner (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Distribution

Australo-Pacific kingfishers are distributed from the Red Sea in the Middle East to French Polynesia, a group of islands in the remote Pacific. The most widespread Australo-Pacific kingfisher is the collared kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris), with is the only species that is found as far west as eastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula as well as as far east as Malaysia and Indonesia. Other species inhabit only a few islands or even a single island. For example, the blue-black kingfisher (Todiramphus nigrocyaneus) is found on New Guinea, Batanta, Salawati, and Yapen, and the Tahiti kingfisher (Todiramphus veneratus) occurs only on Moorea and Tahiti in the Society Islands.

Collared kingfihser (Todiramphus chloris), Leyte, Philippines. Photo by Kai Squires (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Blue-black kingfisher (Todiramphus nigrocyaneus), Papua Barat, island of New Guinea, Indonesia. Photo by Ahmad Yasin Chumaedi (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license).

Society kingfisher (Todiramphus veneeratus subspecies youngi), Moorea, Society Islands. Photo by Richard Hasegawa (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license).

Threats

Forest clearing

The clearing of forests is a major threat to Australo-Pacific kingfishers. Some of these kingfishers are best able survive in primary forest (forest that has never been cut), and their populations decline steeply when forest is cleared. Others have been able to adapt to certain human modifications of their habitat. For example, the Tuamotu kingfisher (Todiramphus gambieri), which has a small population that is only found on the atoll (a low-lying island formed by corals) of Niau, French Polynesia, has adapted to living in coconut palm plantations.

Logging for wood, land clearing for agriculture (including oil palm and kava plantations), and development related to tourism are some of the activities that threaten kingfisher habitats. The replacement of native tree species with non-native species also degrades kingfisher habitats in the Australo-Pacific region.

New Britain kingfisher (Todiramphus albonotatus), Pokili Forest, New Britain. The New Britain kingfisher is considered near threatened, in part due to habitat loss. On New Britain, forest has been logged and cleared to plant oil palm. Photo by Nik Borrow (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license).

A Pohnpei kingfisher (Todiramphus reichenbachii), which lives only on the island of Pohnpei in Micronesia. This species is considered vulnerable due to the clearing of forest in order to plant kava (Piper methysticum). There are also fears that the brown tree snake (see below under introduced species) could reach Pohnpei. Photo by Thibaud Aronson (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license).

Introduced species

Introduced species are another major threat to Australo-Pacific kingfishers, especially those that live on small and remote islands. Introduced species are species that are not native to an island or a region, but that have become established after being brought there (introduced) by humans, either accidentally or intentionally. Two Australo-Pacific kingfishers in particular have declined due to the introduction of new predators to island habitats: the Marquesas kingfisher and the Guam kingfisher.

The Marquesas kingfisher (Todiramphus godeffroyi) or Pahi was originally found on two islands, Hiva Oa and Tahuata, in the Marquesas Islands, a group of remote Pacific islands. The kingfisher is now only found on Tahuata. The population on Hiva Oa was driven to extinction by the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), which is native to the Americas. The owl was introduced to Hiva Oa in the 1920s to control rats, which are also not native to Hiva Oa. Currently, the population on Tahuata is threatened by habitat loss.

A great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) in its native habitat in Calgary, Canada. Photo by Sunny (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

The Guam kingfisher or sihek (Todiramphus cinnamominus) is currently the only kingfisher known to be extinct in the wild. This kingfisher lived only on the island of Guam, an isolated Pacific island. The brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) was accidentally introduced to Guam, probably traveling undetected aboard a ship sometime in the 1940s. The brown tree snake is native to Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea.

Since its introduction, the snake's population has exploded and populations of the Guam kingfisher and some other island birds have been devastated. A captive population of the Guam kingfisher is being maintained with the hopes of reintroducing it to the island someday. Safeguards have also been put into place to try to keep the brown tree snake from spreading to other islands.

A Guam kingfisher (Todiramphus cinnamominus) at the Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, Illinois. Photo by Fred Faulkner (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Original caption: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) wildlife specialist Jess Guerrero holds a brown tree snake retrieved from one of dozens of snake traps hanging on the U.S. Air Force (USAF) Andersen Air Force Base flight line fence in Guam. The USAF and USDA are partners in the effort to contain the snakes and prevent accidental migration of the serpents to Hawaii and other Pacific islands. U.S. Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Lance Cheung." Source: USDA on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Climate change

The world is currently experiencing human-caused climate change, the result of the buildup of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere. Greenhouse gasses are generated by different types of human activities, one of the most notable being burning fossil fuels. These gases absorb solar energy and radiate it as heat, warming the atmosphere. The heating of the Earth's atmosphere has already had profound impacts on Earth's climate, including raising the average global temperature and causing changes in weather patterns.

The warming caused by climate change is also responsible for the rapid glacial melting now observed in mountains and on continental ice sheets, like the ice sheet covering much of Greenland. A large volume of the Earth's fresh water is locked in the massive glacial ice sheets that occur in the Arctic and Antarctic. As the polar ice sheets melt, they add water to the world's oceans, causing them to rise. As the world's oceans warm, they also expand, which also contributes to sea level rise.

The Indo-Pacific region is being and will continue to be impacted by climate change in many ways. One of the most dire threats to islands in this region is sea level rise. Many of the island systems in the Pacific are low lying; even those that rise higher will lose land area as sea level rises. The likely result will be the degradation and loss of terrestrial habitats like those that Australo-Pacific kingfishers depend on.

The coast of Nggatokae Island in the Solomon Islands, showing the effects of sea level rise. The Solomon Islands are some of the islands currently most threatened by sea level rise due to climate change. Several species of kingfishers, including some Australo-Pacific kingfishers, have been recorded on this island. Photo by Alex DeCiccio (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Resources

Websites

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: https://www.iucnredlist.org/

Mission critical: saving an endemic kingfisher on the brink (Birdlife International): https://www.birdlife.org/news/2023/02/17/mission-critical-saving-an-endemic-kingfisher-on-the-brink/

Articles & reports

McKie, R. 2023. Scientists battle to save Guam kingfisher after snakes introduced. The Guardian, 23 July 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jul/23/scientists-battle-to-save-guam-kingfisher-after-snakes-introduced

Winkler, D.W., S.M. Billerman, and I.J. Lovette. 2020. Kingfishers (Alcedinidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World Online (S.M. Billerman, B.K. Keeney, P.G. Rodewald, and T.S. Schulenberg, eds.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, U.S.A. [subscription needed to access content] https://doi-org.proxy.library.cornell.edu/10.2173/bow.alcedi1.01

Videos

The sacred king fisher (Wicked Wildlife, via YouTube): https://youtu.be/SWbRmuHahr4?feature=shared

Scientific articles

Coulombe, G.L., D.C. Kesler, and A. Gouni. 2011. Agricultural coconut forest as habitat for the critically endangered Tuamotu kingfisher (Todiramphus gabieri gertudae). The Auk 128: 283-292. https://doi.org/10.1525/auk.2011.10191

Fitzsimons, J.A., and J.L. Thomas. 2011. Fiji's collared kingfishers (Todiramphus chloris vitensis) do hunt fish in inland waters. Notornis 58: 163-164.