For some years now the Zabludowicz Collection has quietly been inviting artists to the Finnish island of Sarvisalo, a summer hideaway about 90 km east of Helsinki on the Baltic Sea’s north shore. Here artists are given carte blanche to conduct research, produce a site-specific installation or pretty much engage in whatever they want or need to do to advance their practice. While some of the art produced remains in situ, other works make their way into exhibitions around the world or are migrated to the Collection’s storage facilities.

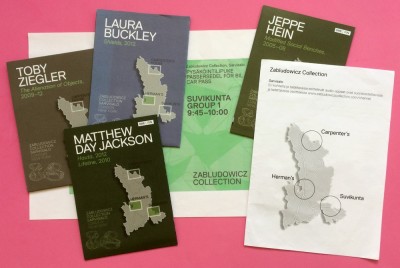

The portion of the Zabludowicz Collection installed at Sarvisalo is spread out across three properties. What limits access to this branch of the organisation is that its locations are interspersed among the island’s residents’ properties. Public access is, thus, extremely limited. For most, the annual Open Weekend offers the only opportunity to tour the sites.

The outing makes for a interesting day trip and wheels are a definite necessity, both for reaching the island and moving between the Collection’s three locations. Sarvisalo isn’t the smallest of islands and no shuttle service is provided. Under the present circumstances, the Open Weekend functions as a practical and necessary compromise for art viewing as it aims to allow access without disrupting the community’s peaceful character. Execution of the event each year is an ongoing work-in-progress. Figuring out what does and does not work and how to best manage visitor numbers continues to be a test.

Any broad survey of art encompasses highs and lows, but here the size of that gap was negligible. Clearly, Keith Tyson‘s Large Field Array, installed in Suvikunta’s new Art Barn, stands out as a memorable focal point. Hours could be spent viewing this fascinatingly diverse installation and this visit provides an almost mind numbing introduction. It totals 293 components, many of which are kinetic. Unveiled in 2016, the work hasn’t been exhibited for a decade or so. This long term installation ameliorates that situation.

Unlike Tyson’s installation, which necessitates the white cube’s unmitigated continuity, works planted outdoors must contend with ongoing climatic shifts. Take Franz West‘s energetic Shlieren/Smears 2010, which, to my mind, benefits greatly from its exterior location. In the diminished light effected by an overcast sky and falling drizzle, this oversized minty squiggle stood out against a shadowy wooded backdrop and conferred with a string of potted flowers set along a promenade that leads to sea.

The grounds hold other treasures too. Consider the inexplicable presence of Matthew Day Jackson‘s Lifeline 2010 for a moment. Has anyone dared call that number? And, if so, what kind of response was received? The unassuming 2-story Dorm House is another case in point. Stepping inside brings one in to contact with more of the unexpected, as its been refitted with lots and lots of PVC plumbing fittings, gravel, pebbledash and glass tiles. that organically flow through inner spaces through its rooms. This site-specific installation was created by Rachael Champion and titled Discoverers of Onkalo 2016.

Herman’s, a former farm and the second tour stop, is also situated on water. Unlike Suvikunta, though, the grounds – but for the performance supplied by a robotic lawnmower – seemed unusually bare. Here I was first directed to a hillock, then descended a concrete staircase and passed through a heavy metal door where I was confronted by Matthew Day Jackson‘s Hauta, or ‘tomb’. Bathed in a faint natural light seeping in through the skylight, this creepy display, featuring a skeleton in a vitrine, was suddenly transformed by the glass box’s mirror-like properties. What once presented itself as an uncomfortably narrow cavern had been converted into a spatial wonder – a complex array of reflections.

Then, of the several works in Herman’s Art Barn, it was Toby Ziegler‘s The Alienation of Objects 2009-2012 that really stood out. Reconfigured for its interior, the installation features a series of abstracted figurative sculptures that are linked by a multi-level and curiously rectilinear track network. I especially liked the way light and shadow plays across the faceted forms and that they can be viewed from perspectives. Learning that these works are based on images pulled off the internet and reworked by means of computer-aided 3D design and real world hand-modelling not only accounts for their present state of alienation, but makes them that much more captivating.

Other significant encounters at Herman’s included Laura Buckley‘s Shields 2012 (shown above) and Sam Falls‘ Untitled (Boat House) 2015 (shown below). I’d seen both works previously when they appeared in Zabludowicz Collection at Helsinki’s Taidehalli (19 March – 24 April, 2016), a group exhibition that presented a sampling of the Collection’s holdings. But, whereas Buckley’s captivating 2-channel video projection filled a single massive wall at Taidehalli, here it formed a 2-part installation. My pictures only document the part situated in the lower space, a vaulted root cellar built of stone. Fitted with perspex discs that reflect, distort and assist with projecting her semi-abstract images, this dramatically different arrangement suggested I was witnessing an entirely different work.

On the other hand, Sam Falls coloured windows and the accompanying photograms realised from the glass panels in failed to inspire a similar response. “Too churchy,” is how one individual described the installation, a comment that I believed rang true. At Taidehalli, a photograph snapped at a distance from the boat house offered a clear view of the composition, but from inside the boat house and the wooden deck running around its perimeter, only fragmented views could be had. The photograms cramped linear arrangement also proved uninspiring.

At Taidehalli, the photograms’ configuration seemed to mock the ordering of the windows by being vertically, instead of horizontally, ordered. Set out in a 3-tier arrangement that also effectively jettisoned the windows’ pyramidal structure, this pairing proved to be playfully contradictory in an alluring relaxed way.

Jeppe Hein‘s modified benches punctuated the romp at numerous times and places. Contributing levity and surprise, these functional art works definitely thwart expectations of how benches should behave. The Collection boasts ten versions that are divided among the 3 locations. By the time I’d reached Carpenter’s, I felt this drawn out rate of exposure made them seem peripheral. The experience got me wanting to see them concentrated at one location – not necessarily sitting next to each other – but situated much more closely together in order to glean a more accurate sense of the series’ diversity and be fascinated by them.

James Ireland‘s You Mistake My Horror For Love 2007, a work that combines natural and industrially produced components, was one of the unexpected highlights at Carpenter’s. From across the yard the sculpture initially comes off as an experiment in formalism, a virtually wall-less framework subdividing space for some unspecified purpose. But moving closer revealed the inclusion of two tree trunk fragments that contribute to and depart from the framework’s generally austere character.

Then, with prolonged looking, I gained an awareness of its real purpose, that of calling attention to its surroundings. The sky and tree tops are reflected in its chrome metal platforms and the horizontal and vertical members of the framework align themselves with many of the contours evident in the property’s buildings and grounds. The structure can also be interpreted as a series of viewing windows. Whereas those that are completely open frame particular perspectives, others closed with sheets of semi-transparent coloured glass contribute mirrored and blurred views. At one point I realised that my focus had been completely directed away from the sculpture. It had me studying the immediate environment and the sculpture presence had, in effect, altogether dissolved.

The final art work visited was Richard Woods‘ Stone Clad Cottage (Sarvisalo) 2011, the painted walls of which upend the look of crazy paving and convey an impression that hovers somewhere between the tenets of folk art and children’s story book illustration. They also call up references to Jasper Johns’ flagstone paintings, but Woods’ hasn’t limited himself to the exterior. He’s gone inside too. In addition to modifying the interior colour scheme, viewers will also discover more than one of his red brick portraits hanging on the cottage’s walls.

The fact that my visit to Sarvisalo neither involved having to navigate crowded galleries nor be bumped by or struggle to avoid people distracted by their audio tours made the experience extremely pleasurable. Wanting to spend additional time looking at particular art works was also balanced by the desire, possibility and impending necessity to complete the tour in good time. It ended up being the best of comprises and I departed Sarvisalo knowing that the tour had provided an excellent introduction to artists whose work I had not yet seen.

The tour also illuminated a number of the challenges facing Sarvisalo. Becoming aware of a range of important issues, such as how to provide public access, adapt art work to withstand the effects of the local climate and manage the longterm care and maintenance of the collection, proved revelatory. Staff members willingness to impart this kind information to visitors made the experience even more momentous.

*Sarvisalo Open Weekend visit day: 19 August 2017

*All photos by writer, unless noted otherwise.