.

.

Director: Tod Browning

Screenwriters: Willis Goldbeck (uncredited), Leon Gordon (uncredited)

By Roderick Heath

The Horror film and controversy have long been conjoined in general understanding, culminating in moments like the infamous “video nasty” debate in the UK in the 1980s. The concern that Horror movies are colonising minds with perverting images, unleashing barely-quelled inner demons, or lending some strange flesh to dark fantasies usually kept secret if not safe, is one that can still drive popular argument. Whilst there were undoubtedly controversial movies before it, Tod Browning’s Freaks is nonetheless the great antecedent of such debates. Freaks is the most fabled, notorious, and elusive of great Horror movies from the first half of the Twentieth century, and such a description could also be applied to its creator. Browning stands as likely the first true auteur of the Hollywood wing of Horror cinema, reaching his apogee of fame with 1931’s Dracula and its follow-up, Freaks. Browning, born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1880 with the real given names of Charles Albert, was the son of a successful builder. At age 16 did what many a youngster has dreamt of, and ran away to join the circus, which had become his obsession. After stints as a roustabout, a barker, a contortionist, a dancer and entertainer on Mississippi riverboats, a magician, a clown, and an acrobat, he achieved notoriety with his buried-alive act, “The Living Hypnotic Corpse,” before moving on to become a vaudeville performer, and adopted his perennial nickname because it was the German word for death. Short leap then to acting in movies, making his debut at age 29, with a vast amount of life and performing experience already behind him. Browning joined D.W. Griffith’s company. In 1915, Browning was involved in a car crash that cost a fellow actor’s life and nearly killed him. The crash was the direct result of the drinking problem that would dog Browning throughout his life and ultimately foil his great talent.

.

.

During his recovery Browning started working behind the camera for Griffith, including as an assistant director as well as playing a small role in Intolerance (1916), but his previous speciality in comedy now gave way to a brooding obsession with physical deformity and ominous melodramas preoccupied with revenge, culpability, illusion, and social exile. Browning’s early feature directing work is hazy, with some uncertainty whether some works he was credited with were ever even actually shot, but he was certainly on the move by 1917. He found success at Universal Pictures directing a string of exotic melodramas starring Priscilla Dean, one of the top leading ladies of the time. Whilst making The Wicked Darling (1919), in which Dean played a slum girl forced into crime, Browning met the star collaborator he’s best-remembered for working with, Lon Chaney, who played Dean’s victimiser in the film. Chaney was already well-known for his incredible feats of physical transformation, and within a few years he had become one of the biggest stars of the silent age, with his make-up and prosthetic effects often bordering on the masochistic, and he became the perfect living canvas for Browning to act out his dark fantasies with. Their true alliance began with 1921’s Outside The Law, in which Browning cast Chaney in a double role as a slimy gangland villain and a kindly Chinese man, with one character murdering the other. Browning and Chaney owed much to the creative indulgence of MGM’s producing whiz-kid Irving Thalberg, and Chaney like Browning had an immediate personal grounding for his fascination with physical difference, as the son of deaf parents.

.

.

Browning and Chaney’s work together included a string of successful, near-legendary movies including The Unholy Three (1925), The Unknown (1926), the gimmicky vampire movie London After Midnight (1926), and the lurid exotic thriller West of Zanzibar (1928). Chaney’s death from throat cancer in 1930 ended the partnership just as Browning was gearing up for Dracula, intended as another Chaney vehicle. Browning’s huge success with Dracula carried multiple ironies. Chaney’s death and pressure from Universal Pictures, obliging him to stick close to the template of the stage adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel once its star Béla Lugosi was cast in the lead, contributed to Browning’s reportedly erratic involvement the shoot, with its director of photography Karl Freund gaining credit for rescuing the picture. Dracula’s enormous, zeitgeist-altering success papered over many sins, and Browning was brought back to MGM, where he had made most of his Chaney vehicles: despite the studio’s general resistance to making horror films, the genre’s enormous profitability couldn’t be ignored, and Browning, as a known quantity, seemed the man to make them. There Browning made Freaks, with proved another career-damaging fiasco, before his impudent, self-reflexive remake of London After Midnight, Mark of the Vampire (1935) and The Devil-Doll (1936), his last major horror movies, mixed in with other movies, before his last feature work, 1939’s Miracles For Sale.

.

.

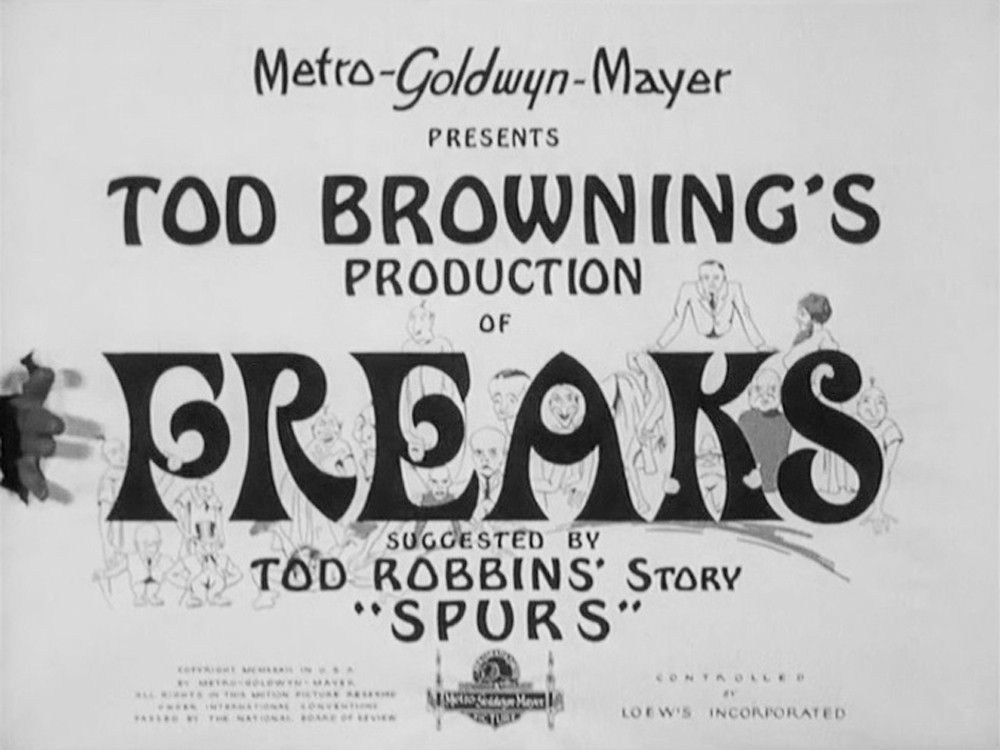

Today Dracula’s reputation has shrunk greatly, perhaps a little too much: the film’s aesthetic of eerie stillness and somnambulist dread convey much of the book’s flavour in spite of the clumsy elements transposed from the stage. The central performances from Lugosi and Edward Van Sloan as Professor Van Helsing are still perfect, and even its oddly evasive approach to physical horror gives it a unique charge, as if grazing the edges of truly obscene things. Freaks is nonetheless easily Browning’s best sound film, and very likely his masterpiece. Browning took inspiration from the short story “Spurs” by Tod Robbins, the tale of a circus bareback rider named Jeanne who marries a dwarf named Jacques for his money whilst actually loving her performing partner Simon. Browning kept little of Robbins’ story except for the specific triangle mentioned above and the fateful act of the bride carrying her husband at their wedding feast. Freaks’ calamitous reception from studio, censors, and eventual audience is an irreducible part of its legend: Thalberg backed the film right through filming but disastrous preview screenings made him cut half an hour from the 90 minute film, and when the film proved only intermittently popular it sold on to the infamous early independent exploitation filmmaker and distributor Dwaine Esper, who added a hyping moralistic scroll to the opening. Today the opening with the MGM logo and the single title card have been restored: the title card proves to be a poster torn through by a hand in a brusque and potent gesture that confirms this film will be something unusual.

.

.

The flashback structure harkens back to Robert Wiene’s ever-influential Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1919), and the films share a circus setting and inside-out sense of social reality. A sideshow barker (Murray Kinnell) entices an audience with the strange and shocking story of one of his human exhibits, offering a salutary message to the crowd of gawkers: “You laughed at them, shuddered at them, and yet but for the accident of birth, you might be even as they are,” and notes that, “Their code is a law unto themselves – offend one and you offend them all.” The barker then moves to the side of a pit wherein resides “the most astounding living monstrosity of all time…she was once a beautiful woman.” The twinned concepts of beauty and monstrosity are immediately couched in the language of spectacle and showbiz, each necessary to the successful purveying of entertainment-as-business and which also provides a way of living to those who fall at either extreme of the dichotomy. The opening gives away the ultimate twist of the story, as Browning dissolves from the barker noting this particular former beauty was once called “the peacock of the air” to the image of Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova) perched on an acrobatic swing high under the circus big top. The peacock of the air eventually becomes the fowl in the pit in Browning’s particularly savage and punitive take on the familiar tradition of dark storytelling, one built around a morality play climaxing with highly ironic punishment. Robbins’ gleefully sadistic tale resolved with Jacques murdering Simon and forcing his wife to carry him right across France like the horses she used to ride, digging spurs into her back all the way.

.

.

The contradiction built into Freaks as a film, the simultaneous demystification and humanist embrace of the “freaks” themselves and the ultimate segue into their nightmarish eruption as a force of strange vengeance, is complex and not entirely free of qualms. But it’s also very much the film’s ultimate subject: the imagery of the freaks chasing down their prey with grim and homicidal purpose ought to be scarcely more disturbing ultimately than the many instances of contempt and verbal abuse turned on them throughout the preceding hour of cinema, with many of the “normal” people portrayed as attractive but loathsome and the “freaks” as a warm, proud, individualistic bunch. An early scene sees a gamekeeper, Jean (Michael Visaroff) leading his estate owner employer (Albert Conti) through forest, gabbling about glimpsing unnatural creatures dancing in stygian scenes in the depths of the estate, only to find the freaks picnicking and at play under the care of Madame Tetrallini (Rose Dione), their mother figure amongst the circus employees. When the intruders disturb their play the “children” as Tetrallini calls them scurry to her in fright despite her admonitions, and the estate owner contrasts the rabid offence of his gamekeeper by graciously giving them permission to stay and not acting at all perturbed. Browning quickly makes the freaks seem normal and defines them as innocents who have to buy their moments in the sun with an expected edge of risk of reviling and rejection.

.

.

Browning and his screenwriters Willis Goldbeck and Leon Gordon offer the stable of freaks in the unnamed circus, which is travelling through what seems to be rural France that is the setting for the entire film, as both a world apart but also as just another coherent working community, granted collective integrity and independence precisely and ironically because of their peculiarity. There’s no interest in the circus folks’ interactions with patrons, with the estate owner and the groundskeeper the only outsiders glimpsed, and they’re sufficient to represent the world. Much of Freaks is indeed more an oddball, gentle sitcom rather than a horror-thriller, as Browning emphasises the interactions between the circus denizens, some of it encompassing the casual cruelty of the usual towards the unusual, but most of it mediated with the gentler by-play between characters, but with the actual plot simmering away from the earliest frames of the flashback, as Hans (Harry Earles), a midget in the circus, stares longingly up at Cleopatra as she dangles from the highwires, with his fiancé Frieda (Daisy Earles) gazing on helplessly as she registers his smitten distraction. Hans is one of Browning’s most habitual character types, a figure who feels his humanity all the more ferociously despite not being perceived as an entire person. “They don’t realise that I’m a man, with the same feelings they have.” Hans reacts with aggrieved vehemence when he feels his sovereignty and his instinct for protectiveness have been offended, shrugging off the familiar mockery of most of the circus hands but standing up with unbridled rage when they extend the same mockery to Cleopatra when she’s playing up to him.

.

.

Browning’s films with Chaney fixated on figures who both invite and deal out mortification and whose perversities and neuroses are written in the flesh, most particularly the antihero Alonzo of The Unknown who elects to have his arms surgically removed so he can emerge from a life of hiding, an act designed to make real his extended performance, and Dead Legs of West of Zanzibar, whose physical paralysis is explicitly connected with his moral rot and desire to debase others, as he drives his adopted daughter into forced prostitution in a campaign of revenge. In Dracula he mostly passed off the imagery conveying such grotesquery onto the world surrounding the characters, particularly in the visions of Dracula’s castle, alive with seething, crawling, scuttling animal life, a visual motif he repeated in Mark of the Vampire as well as proffering a multilayered, self-satirising joke about role-playing and the deceptive appeal of woolly-minded narratives. Later, in The Devil-Doll, Browning found a new metaphor for exploring the artist figure and his literal human puppets as vehicles of delight and menace. Freaks as traits in common with all of these but with an inevitable caveat: Browning’s stars are entirely themselves, requiring no make-up or fakery, presenting a wing of show business ironically defined by inescapable reality rather than hiding from it or rewriting it at whim.

.

.

Hans also possesses another quality Browning constantly gave his protagonists, a grim need to ultimately confront the moment when he will be exposed and humiliated. Earles had played the leader of the gang in The Unholy Three, where he gleefully tore to shreds the enforced childish image for midget actors by playing a vicious, dictatorial master criminal (that film was also based on a Tod Robbins story). The relationship between Hans and Frieda is a core facet of the drama and one where Browning takes their emotional experiences with absolute seriousness and psychological attentiveness, allowing Harry both dignity in his transgressive passion, seeing nothing sick or aberrant about his erotic needs stoked by Cleopatra, even as he enacts the arc of a thousand chumps in noir films like, say, Elisha Cook in The Killing (1956), haplessly under the sway of a beautiful, heartless woman who nonetheless hooks him not just by appealing to basic erotic urges but to his complex, masochistic streak, the desire for aspiration and degradation constantly cohabiting. Frieda’s maternally styled affection for Hans is the kind of selflessly suffering love that fuelled a thousand romantic melodramas in turn. Browning allows the couple a depth of pathos and emotional intricacy, and his shooting is attentive in visual language to such intensity and schismatic feeling, as when he has Hans abruptly turn from Frieda and walk out through a door where he hovers beyond the threshold, the two contained by frames within frames in their different spaces of angst and longing. “To me you’re a man, but to her you’re only something to laugh at.” Ironically the casting of the two Earles, who were actually brother and sister, is just about the kinkiest touch in the whole movie.

.

.

Browning presents both authorial and audience surrogates in the clown Phroso (Wallace Ford) and performing seal trainer Venus (Leila Hyams), who form a quirky romantic coupling as the story unfolds and maintain an entirely equable friendship with the freaks. They contrast many of the other circus workers, like the two jerks who tease the “half-woman half-man” Josephine Joseph. Josephine Joseph fancies the circus strongman Hercules (Henry Victor), who is first introduced breaking up with Venus, who he kicks out of his trailer. In one of the film’s many, notable pre-Production Code touches, they’re depicted quite directly as being merely shacked up together. After storming out on Hercules, Venus pauses to launch into a rhetorical harangue at Phroso, who listens in bewilderment as he strips off his performing costume, before suddenly flaring up, chasing after her, and delivering his own by way of angry consolation. Phroso is Browning’s artist hero, granted an extra degree of awareness in some things but slightly too distracted by his creative process in others, as when he gets too absorbed in building a prop for a gag he thinks up to remember to go on a date with Venus – Browning offers a good visual gag as it seem Phroso is having a bath out in the open before the unabashed Venus, only to pull back and reveal Phoros has cut the bottom out of the bath and has mounted it on wheels, and is only stripped to the waist. This nonetheless segues into Phroso and Venus’ bashful first kiss. Phroso’s acts notably depend on him playing games with his own physical identity, making a quip, “You should’ve seen me before my operation,” and dressing in costume that allow him to suddenly seem headless. Rather than aspiring towards the appearance of strength and normality, his theatrical project is to be more like the freaks.

.

.

Much of the film’s midsection is similarly given over to portraying the peculiarities of life in this subculture, laced with hints of perverse experience, particularly in the case of the conjoined twins Daisy and Violet (Daisy and Violet Hilton). Daisy is engaged to marry one of the circus performers, the stammering Roscoe (Rosco Ates), who regards Violet with the kind of pecking hostility many a husband would turn on a sister-in-law constantly hanging around, and it’s made clear the sisters share sensations: Roscoe warns Violet off drinking too much because he doesn’t want a hungover wife. Later, famously, when Violet becomes engaged to a lothario, he kisses her and Daisy quivers in shared ecstasy. This follows Phroso and Venus’ kiss and precedes Roscoe and Phroso glimpsing Hans leaving Cleopatra’s trailer, in a roundelay of vignettes grazing the edge of the peculiar erotic life of the circus denizens, although in one case of course the appearances are deceiving. Roscoe is introduced to the fiancé, who graciously tells his soon-to-be-brother-in-law, “You must come to see us sometime.” Roscoe’s anxiety about being unmanned by his unusual marriage is at once rich and understandable considering makes a living himself through blurred gender identity, dressing up every night as a “Roman maiden” in some act. The comedy of manners plays out simultaneous to the darker drama. Roscoe makes Phroso crack up when he comments that Cleopatra “must be going on a diet.” In fact Hercules quickly catches Cleopatra’s eye and becomes her conspiratorial lover, and when he glimpses Josephine Joseph gazing on in lovelorn disquiet, he punches them in the face, much to Cleopatra’s amusement. This is actually the most overt and shocking moment of violence actually seen in the film.

.

.

The palpable reality of the performers makes Freaks as much an historical document as a movie. Some critics have theorised Browning intended Freaks as a riposte to the eugenics movement, then at a height in the US, by showcasing the ingenuity and physical genius of his performers, as well as their personalities. Certainly the film’s general pitch counters the kind of thinking behind such a movement, seeing the specific worth in the variously abled performers, and comprehending their often amazing physical attributes, which provide Browning with much of his movie. One wry scene sees an acrobat yammer on about his act to Prince Randian, ‘The Living Torso,’ who has no arms or legs but patiently lights himself a cigarette purely with his mouth, after he which he announces proudly, “I can do anything with my mouth.” Johnny Eck, ‘the Half-Boy,’ born with sacral agenenis leaving him without legs, trots about on his hands with an astounding sense of motion and balance. ‘The Armless Girl’ Frances O’Connor, primly and precisely eating and drinking entirely with her toes whilst chatting with Minnie Woolsey, aka Koo Koo ‘The Bird Girl’. Three people with microcephaly, or pinheads as they often were called at the time, appear in the film, including one marvellous vignette of Phroso jesting with the performer Schlitzie (who was male but is referred to in the film as female), in a scene that breaks down any barrier between the movie and capturing Ford and Schlitzie interacting, Schlitzie’s bashful delight as Ford teasing her about her new dress before Schlitzie becomes mock-angry with him when he offers to buy one of the others a big hat, giving him a slap, and then a reassuring pat.

.

.

Freaks’ European setting, despite the large number of very American actors in the movie and the strong aura they keep alive through the film from the American circus community Browning had known, situates it squarely in the emerging Hollywood gothic horror movement’s air of displaced and cloistered reality. That thin wedge of divorcement allows Freaks, like the previous year’s Frankenstein, to present a thorny commentary on social norms without seeming to. Like James Whale’s film it revolves around communal rejection of the “abnormal” and climaxes with an act of mob justice, but where Whale at that point was could only signal a degree of empathy for the monster but had to ultimately side with the wider forces of society that sets out to kill the destructive reject, Browning wholeheartedly embraces the outsider perspective with all attendant social and political meaning. His freaks are a community apart, both entrapped by the circus but also protected and allowed to be functional within it. That communal identity and integrity have appeal, and Hans, despite becoming independently wealthy thanks to an inheritance, still sticks with the circus because to leave it would be to leave society, a notion confirmed at the very end, although by then it’s an act of choice. Once Cleopatra hears about Hans’ inheritance, it encourages her to move from merely profiting from Hans’ occasional gifts and gaining private entertainment from his ardour, to thinking about claiming his riches through marrying him and then killing him. Frieda accidentally reveals Hans’ fortune to Cleopatra when she makes a pathetic entreaty to the willowy beauty not to play around with Hans.

.

.

The ready potential for a circus setting as a metaphor for moviemaking and the attendant industry of beauty-manufacturing is something other filmmakers haven’t neglected, from Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show On Earth (1952) to Sidney Hayers’ Circus of Horrors (1960). Freaks goes deeper and bites harder in beholding the circus as the ideal amphitheatre for such preoccupations, taking to an extreme the negotiation between an audience fused from painful flesh and taunting dreams and its objects of illusory beauty, and the will to tear those objects to pieces when they prove human. For Browning, who had been a part of the larger but in many ways just as insular and segregated world of working entertainment for his entire life, the freaks are a particular example of a loving human commune, and obliges the audience to identify with them as surrogates in the midst of the Depression and the usual business of surviving in the world. Cleopatra and Hercules are mockeries of the usual business of movie stardom and its obliged identification with the usual winners in society, the strong and the beautiful, surviving like vampires off the figurative and literal theft of others’ time, money, and aspirations, and repaying with contempt and violence. Baclanova’s casting played on her other best-known role in The Man Who Laughs (1926), where she played the fetishist Duchess turned on by caressing the edges of ugliness. Here by contrast she plays a person pretending to indifferent to physical difference, but with a similarly extreme evocation of sensual cruelty and egotism.

.

.

The film’s infamous apotheosis comes when Hans and Cleopatra are married and hold a celebration attended by the friends of the bride, which in Cleopatra’s case is just Hercules, and Hans, being his sideshow pals. Browning even gives the episode a title card, as in a silent film, to give it special import: “The Wedding Feast.” The circus folk all do their party piece for the sake of entertainment in the giddily cheerful moment, from Koo Koo doing a weird shimmying dance on the table-top, to a sword-swallower and fire-eater doing their bits. Cleopatra wastes no time in beginning her husband’s slow death as she poisons the wine he’s drinking, and gets swiftly drunk to the point where she scarcely conceals her passion for Hercules and treats Hans with patronising good-humour, pinching his cheeks and pouring him cups of poison. One of the dwarves, Angeleno (Angelo Rossitto), proposes they hold the ritual induction for a new member of their circular with a loving cup, which he passes around whilst trotting along on the feast table, and the freaks begin chanting, “One of us! One of us! Gooble Gobble, gooble gobble!” The song is both childlike and goofy but also nagging and perturbing in its monotone repetition, the sound of the community rejoicing in their own weirdness, a veil dropped. The amplifying rhythm of the editing, both vision and sound, blends the chanting with Cleopatra and Hercules’ raucous laughter into a hysterical gestalt, until Hercules comments to Cleopatra, “They’re going to make you one of them, my big duck!”

.

.

Squinting drunkenly to behold the proceedings more closely, Cleopatra’s amusement abruptly wanes, as she stands and beholds the scene now as a stygian vortex threatening to consume her, and she reacts with sudden, noisy rage, bellowing, “You dirty, slimy freaks! Freaks! Freaks!” The horrendous force of Cleopatra’s abuse and rage lands like a collective slap to the face, and she flings the contents of the cup at them, driving them out. When Hans protests she’s made him feel ashamed, Hercules and Cleopatra compound the humiliation as the strongman scoops him up and deposits Hans on Cleopatra’s shoulders, and as she forcibly piggybacks him around the ring Hercules grabs up a trumpet and begins blowing it merrily, at which point Browning mercifully fades out. This scene sees the film’s uneasy aesthetic, with its observant, often wry tone interspersed with darker notes of mockery and bigotry, abruptly cohere. The way the feast builds in intensity into a spectacle of rejection and cruelty is almost without parallel, treading the finest of lines in evoking both sides of the equation, the group enthusiasm of the freaks in their ritual of acceptance and the repulsion of Cleopatra. She comprehends the ritual’s meaning as a reversal, however malice-free, of the familiar power dynamic: suddenly the secret lode of force is not located in being superior to or even accepting of the freaks, but in their act of accepting, and Cleopatra experiences the moment as, in quintessential Browning fashion, deep humiliation. The party degenerates into a sickly mockery of family dynamics – Cleopatra and Hercules treat Hans as their child in order to reclaim their authority.

.

.

The next day, the two “normal” people make their apologies to Hans, using their drunkenness as an excuse and all but demanding acceptance of the apology because it was all “just a joke.” Which points to the key quality Freaks remains painfully relevant even as its setting and most of its particulars have faded into vague cultural memory and surreal hyperbole, in its comprehension of the little games of dominion and dominance involving things like who has the right to laugh at who enacted all day, every day in society, with the swaggering bullies playing the aggrieved parties in being obliged to act contrite. Hans, troubled and ill, soon collapses as Cleopatra’s poisoning takes effect, and a doctor only diagnoses ptomaine poisoning. Nonetheless the wedding feast has alerted the other freaks that something sleazy is going on, and they form a silent, attentive cabal who now focus their collective attention of proceedings, hovering with silent, boding interest. Their staring presence discourages Hercules from assaulting Venus when she confronts him about her suspicions. Nonetheless he and Cleopatra agree that Venus must be silenced. Meanwhile it becomes clear that far from oblivious to what the couple are trying to do to him, Hans is now aware he’s being poisoned, as Angeleno visits him as he feigns sickness, and Hans mimics Cleopatra’s assuring ministrations with a queasy smile. As the circus caravan heads on to another town along a muddy road amidst a thunderstorm, Cleopatra continues to poison the bedridden Hans whilst Hercules moves break into Venus’ trailer and kill her.

.

.

Here, Browning finally shifts into outright horror imagery and an eruption of action that, whilst hardly arbitrary, nonetheless presents a radical stylistic and thematic reversal appropriate to the theme of tables-turned vengeance. The idea of the “code of the freaks” as mooted by the narrating barker, whilst certainly codswallop invented for the film, nonetheless has the pricking insistence of a campfire tale, an idea promulgated to frighten the young and the foolish into being a tiny bit mindful of what they say and do, and might have had some roots in the real culture of the circus. The thunderstorm provides pummelling rain and flashes of lightning that nicely punctuate the dramatic pivot of the entire movie, when Hans suddenly sits up his bed as Cleopatra tries to ply him with poison and demands the bottle she has in her pocket. Browning weaves an increasingly odd, tense, eerie mood, as Hans’ friends hover and Angeleno blows a creepy tune on an ocarina, before the menace becomes overt, as the visitors unveil a jack-knife and a gun. Baclanova handles the moment when the penny drops with memorable poise, freezing with suddenly wide, glaring eyes and vanishing fake smile as Hans demands the poison bottle. Meanwhile Hercules slips out of his trailer and drops back to attack Venus in hers, whilst Frieda, having eavesdropped on Hercules and Cleopatra making plans, warning Phroso of his intentions. Hercules smashes through the door of Venus’ trailer, but Phroso manages to catch him and the two struggle in the mud. Hercules is skewered with a knife by a dwarf as he throttles Phroso, and the wounded strongman squirms away in the mud as the freaks advance on him. Cleopatra’s trailer hits a broken branch and breaks an axle. Cleopatra flees screaming into the rainy night, chased by Hans and the other little people.

.

.

Freaks’ ploy of sustaining a tone to proceedings that seems at first to belong to a different genre but also calmly sets the scene for a radical shift, and eschewing overt terror and the stylisation of the Expressionist-style Horror film until an eruption of jaggedly ugly violence, has proven a source of real power over the intervening decades, power other genre filmmakers have channelled. Movies like The Wicker Man (1973) or Audition (1999) with their similarly jarring shifts from sustained eccentricity to hideous reckonings might still exist without it, but its influence feels crucial, as well as its less immediate echoes through art-house filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini, who would repeatedly pay tribute to its rarefied evocation of the circus as a place apart from society where social laws become both relaxed and microcosmic. Here too are inklings of David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1978), with its complete entrance into a nightmare zone where the humanity of the misbegotten and mangled becomes too terrible to bear. The finale, discomfortingly, depends on the sudden reversal of the way the freaks have been presented until now: where before the film normalised them, suddenly Browning offers them scuttling through the rain and mud with insinuating motion, turned to pure nightmare fuel.

.

.

On the one hand, this seems to contradict the message of the film until this point, as Browning literally and purposefully makes the freaks dirty and slimy as per Cleopatra’s words. But the real charge of the sequence is in the spectacle of the freaks’ surrendering of their hard-won humanity for the sake of revenge, a spectacle consistent with Browning’s other works: to suddenly see even the gentle Schlitzie as an armed and dangerous being is a genuinely disturbing spectacle. To be human is to also have a dark, dangerous, wilful side as well as a sense of justice, two innate qualities that can’t always be easily separated especially with a group such as the freaks who are without recourse, and the freaks get things done as they will. The finale obviously suffered greatly from Thalberg’s editing, as well as the postscript: the extant film dissolves from the sight of Cleopatra screaming as she’s chased through the woods back to the wraparound sequence of the barker recounting the story. His concluding words embrace ambiguity, as if he’s been an unreliable narrator: “How she got that way will never be known. Some say a jealous lover. Others, that it was the code of the freaks. Others, the storm. Believe it or not, there she is.” Browning reveals what’s left of Cleopatra, now scarred, with both her legs and perhaps her tongue cut away and possibly left insane, making some sort of living jammed into a duck costume for the amusement of the crowd, left subsisting at the nexus of human and inhuman, sense and nonsense, served as erotic travesty.

.

.

Originally, it was supposed to be made clear that this was taking place in a dime museum called Tetrallini’s Freaks and Music Hall, suggesting a move from Madame Tetrallini to give her stable a permanent home. It was also made clear that Hercules survived the freaks’ vengeance but was glimpsed singing in a high voice as another act in the museum, hinting he had been castrated. As it is, Freaks elides such clarification, and indeed, the glimpse of the mutilated Cleopatra suffices as a punch-line, with all its grim and perverted implications and final embrace of a total, hysterical devolution into dream-logic and sadistic fantasy. In some prints, the film ends with this as the appropriately ghastly last image, but there’s a coda in others depicting Hans now living in a mansion, having cut himself off from other people, only to be visited by Phroso, Venus, and Frieda. Where the barker’s narration hints at unreliability, the possibility that everything seen and heard in the account of the duck-girl’s creation is phooey, the coda renders it inarguably true. It also tries to mitigate the fact that Hans is seen amidst one of the cabal chasing Cleopatra down. Frieda assures him she knows he tried and failed to turn his friends from their dreadful punishment, and his current isolation is driven by guilt, eased finally by the couple reconciling. The coda might well have been shot by Thalberg in an attempt to mitigate the bleak splendour of the climax with a note of reassurance, and its does work to an extent, in that it gives the romantic triangle that was at the story’s heart a nominally happy ending. But nothing can quite win out over the image of the twisted, feathered Cleopatra squawking away in the sawdust…

I’ve always loved this film, and have been lucky enough to introduce it to both friends and family. Some agree, some don’t, but there’s no denying the sheer audacity and groundbreaking brilliance of Browning’s masterpiece. Thanks so much for providing a fresh take! Enjoyable reading as always!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Turafish. Yeah, it’s a confronting movie and not always a comfortable or comforting watch. But its greatness is undeniable. Thanks for commenting!

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is the best writing on Freaks I’ve seen anywhere online. Thank you for it!

LikeLike

Thank you Mr Robey!

LikeLike