An interview with Federico Brown

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 29 August 2023

MiniBio: MiniBio: Prof. Federico Brown is currently a principal investigator at Universidade de São Paulo in Brazil, where he focuses on evolutionary and developmental biology. Federico began his career in Ecuador, where he worked as an undergraduate in the lab of Prof. Eugenia del Pino. This is where he first found his passion for EvoDevo, and when he first had the opportunity to work at the Galapagos islands as a field research assistant. After his undergraduate studies, Federico earned a Fulbright scholarship to do his graduate studies in the USA. He went to Seattle, to the lab of Prof. Billie Swalla, where he worked on ascidians. During this time he also had the opportunity to work in Friday Harbor Labs. He later went to the Max Plank institute for developmental biology in Tübingen, Germany, as a postdoctoral scientist. He then returned to Latin America as a principal investigator in Colombia. After several years as a principal investigator, he moved to São Paulo, Brazil, where he currently works. During his career, in addition to his research work, Federico has been heavily involved in outreach and scientific communication activities including deploying Foldscopes for students in remote regions, and the generation of a videogame called Finch Quest. In this interview, Federico also emphasizes the value of outreach, as well as the uniqueness of being a scientist in Ecuador or Brazil – two countries with immensely unique biodiversity, which serve as a source of biological inspiration.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I think this goes back to when I was a child. I used to play a lot in the garden, mixing all kinds of food and things I would find in the kitchen. I wanted to make everything explode. I loved chemistry and I loved to pretend I was a scientist. At some point I wanted to be an astronaut, until I realized I would have to study physics and I didn’t like physics as much as I liked other subjects at school. So eventually I ruled out different disciplines in science. I saw myself as a scientist, but I wasn’t sure about exactly which type of scientist. Then I ruled out subjects in high school, but Biology always seemed like a good option. Also, I am from Ecuador, and my father always loved the outdoor activities and being in touch with nature, so I did this a lot while growing up. He worked in the oil industry in Ecuador, so for his work, we traveled a lot in the Amazon Forest, and this left a long-lasting impression: all this abundance in nature. This helped me define that I wanted to be a biologist. I think what was also impactful for me was to have been able to study the BSc in Biology in Ecuador. I had considered going to Germany to study genetics, but my father influenced me to stay in Ecuador. And I now feel this was a great piece of advice – this allowed me to study in Ecuador, a degree for which Ecuador is a hub – one of the best places in the world to study biology, with its unique nature and biodiversity. It’s the equivalent of studying Art in Italy – you just walk everywhere, and you see life in all its forms everywhere. We had a lot of field trips, where we traveled around Ecuador. It was easy to fall in love with Biology.

You have a career-long involvement in developmental biology, zoology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

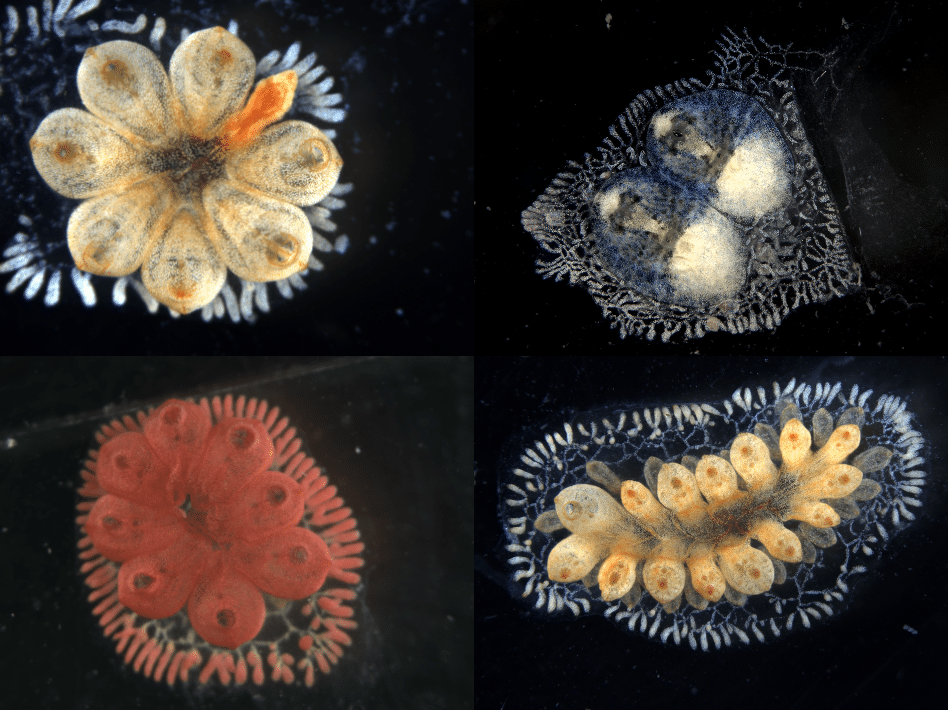

I joined the Faculty of Biology at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. I started looking for internship opportunities and also jobs. I wanted to live by myself, and so that’s when I started working with Prof. Eugenia del Pino, who is probably the best scientist we have in Ecuador. She was working on frog development, and this topic and the experience altogether was an extremely valuable phase of my career. My first paper was written with her and I think she has had a huge influence in my career. In her class we read a book called ‘The Shape of Life’, which I think has been the inspiration for many evolutionary and developmental biologists of my age. Ruddy Ruff wrote this book in the 1990s, and it was an inspiration for a lot of scientists who wanted to gain a deeper understanding of biological processes beyond model systems. I think this book and Eugenia’s work on frogs in Ecuador really opened up that avenue and triggered this interest in me. So for my PhD I joined the field of evolutionary developmental biology, otherwise known as Evo-Devo. I really loved the topic of development and studying developmental processes during the reproduction of frogs, but I wanted a more evolutionary perspective on this. So I ended up applying to several places around the world. EvoDevo was a field that was just emerging and gaining momentum around that time. I earned a Fullbright scholarship to go to the USA, which excluded other possibilities I was considering in France, Australia, Canada and Germany. In Ecuador we don’t have PhD programs, so I had to leave anyway. I was honoured to receive the Fulbright fellowship, which allowed me to go to Washington, specifically to Seattle to the lab of Billie Swalla to work on a different chordate – not vertebrates this time, but ascidians. Ascidians are very interesting because of their phylogenetic position- they are still invertebrates, they don’t make bones, but they are in a position close to vertebrates. This opened up many more questions about evolution, about zoology, about how animals evolved, and in that PhD I also worked in Friday Harbor Laboratories. I took some courses there which were truly inspiring, where I learned about embryogenesis in more than 10 different phyla. This is how I started becoming more focused into zoological questions and evolutionary biology. I like plants and other fields in biology, but I think evolutionary questions and understanding how animal forms evolve and how they reproduce is what drives the question that now my lab investigates and addresses. During my PhD, while working with ascidians – which is an excellent developmental model, but not a good model for genetics or molecular biology – I faced some limitations with them as a research model. I wanted to work with a system more amenable to genetic manipulation, to ask evolutionary questions. So I started looking into other invertebrates and I ended up working with nematodes in Ralf Summer’s lab in Tübingen, Germany, at the Max Plank Institute for Developmental Biology. He was interested in both development and evolution, and I was there for 2 years – very inspiring years. Just after I got a postdoc offer in Tübingen, I got an offer for a faculty position at the Universidad de los Andes in Colombia. I always knew I wanted to return to Latin America, and around that time, there were very few positions. Finding a position for evolutionary and developmental biology in Latin America was really rare so I could not reject this offer. I did a shorter postdoc than expected in Tübingen and then I went to Colombia to start my faculty position. I spent 3 years in Colombia. I worked in a great institution and got to know excellent scientists. As time passed, I kept getting comments by colleagues expressing concern as to how I was going to develop my career in Colombia, when many of my research questions were on basic science, especially when most funding is dedicated to applied science. I realized it was going to be very hard to keep basic science questions in my lab if I stayed there, so I started looking for other options. At the time, in 2013, Brazil was thriving in terms of investment for scientific development and technology and innovation. The University of São Paolo opened a faculty position for Evo-Devo, and I applied. I also wanted to work in a public university – in Colombia it was private. I am convinced that knowledge should not be limited to those with privileges, so for me being in a public university was important. Those were all decisive factors for deciding to come to São Paolo, Brazil, where I currently am. I’ve always tried to keep connections to Ecuador though – I was born in Quito, and my family is there.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Ecuador, from your education years?

I think Ecuador has a lot of issues in higher education – I had to leave the country in order to do doctoral studies in Biology. Despite this, education at undergraduate level was really good, but I think there aren’t enough options for graduate school. I think Ecuador deserves more graduate programs and permanent investment in higher education and research. I left Ecuador in 2002, and until today things haven’t changed much. I have these criticisms, but I also have praise to give! The positive is that to study Biology in a country full of biodiversity, your questions, your interests, your driving force and energy will have a lot of input in the science you do. There are so many unique animals and plants to study all around you. Continental Ecuador and its richness in the mountains, valleys, rivers, etc, serve as inspiration, but there are also so many wonders beyond, like in the Galapagos islands: a hub for evolutionary biology. I had the chance to go to the Galapagos to do some research. Great research has come out from the islands – for example Peter and Rosemary Grant in Princeton have done some of the most inspiring research in evolutionary biology over there. As an undergraduate student, I had the opportunity to work as a field assistant there. In collaboration with the Grants, we collected finch embryos as part of a project led by a former postdoc at Cliff Tabin’s lab in Harvard – his name is Arkhat Abzhanov and he is now faculty in the UK. He recruited undergraduate students in Ecuador to do field work, and these opportunities were unique to us. This model of research collaborations, where foreign researchers working in Ecuador involve local students is positive.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a group leader at Universidade de São Paulo?

USP is a huge University and it requires that all faculty get involved in the main academic fields: research, education and outreach, as well as administrative duties. So my day to day life is a mixture of these things. Most of my day is spent doing research and writing. I meet with my students, we talk about research, I supervise their projects and we together define the next steps for their projects. We have masters, doctoral and postdoctoral students as well as undergraduates. I teach ‘Developmental Biology’ and give lectures in the ‘Vertebrates’ course for undergrads in the Biology program, and also give lectures on the evolution of the nervous system as part of a ‘Biology IV’ course for undergrads in the Molecular Sciences program. I also teach ‘Comparative Embryology of Marine Invertebrates’ and ‘Evolution of Coloniality and Modularity’ for graduate students in the Zoology and the Comparative Biology programs. These are courses I teach, mostly during the second semester of the year, and the first semester is filled with research duties instead. I also teach at the CEBIMAR (Centro de Biología Marinha) at USP, which is 3 hours away from the main USP campus. This is where I have my animals too.

In terms of outreach, we try to get involved in different projects. We try to deliver Foldscopes to communities in São Paulo. A few years ago, at the inaugural meeting of the Pan-American Society for Developmental Biology that took place in Berkeley in 2015, Manu Prakash from Stanford, came to the meeting. He is the inventor and driving force of Foldscope. He wanted to meet the Latin American community, and he brought us many foldscopes for teaching. During the pandemic, I sent foldscopes to students by post, so that they could use them to carry course projects at home, as we could not meet for laboratory session at the university. I am currently organizing an outreach program with students that used foldscopes in their course projects at home– there’s a few efforts at our Institute to include low income communities living around campus in Biology research, and I want to expand our contributions via Foldscope. I think in Latin America, outreach is only slowly becoming part of what being an academic entails. The tradition of outreach for academics is not as strong as in other places, but I think it’s hugely important because of the differences in socioeconomic status and what that represents in terms of access for low-income communities. For young people to even consider a scientific career, I think it is very important that we do outreach.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Ecuador?

Yes, of course. This is one of my favourite activities – engaging with colleagues in Latin America. We have too many challenges that are common to us all. I’m part of TYAN-TWAS (The Young Affiliate Network of The World Academy of Sciences), a network of professors from the developing world that formerly served a 5 year period as Young Affiliates for TWAS. A few months ago, some of us organized an event in Bolivia, called the First Summer School of TWAS. We had biochemists, chemists, and people from biological sciences involved in doing a short training course that lasted one week. The current president of TYAN is very interested in supporting South-South programs where professors of the Global South travel to other countries in the south in research missions for capacity building, scientific skill exchange, and to build connections and collaborations before returning to our countries. This event was locally organized by chemist Leslie Tejada from the Universidad Mayor de San Andres – by the way I saw you interviewed many people from there for this Focal Plane series. Beside the students that participated in our courses, we met the UMSA chancellor and the vice-president of the Academia Nacional de Ciencias there, because it’s important to have the local and regional leaders involved in this type of programs. Among our activities, we included meetings with ambassadors of Latin American countries and representatives of the Bolivian Ministry of Education and Vice-Ministry of Science and Technologyso that we could request continued funding to expand these events into more enduring programs. The first of these experiences happened in March this year, and we are planning to carry a second event in November this year. Overall we find much interest in these missions, but there is a lack of organized programs where we can do this type of thing. Most programs are North-South, and almost none South-South – I feel this has to change. Especially because people with similar challenges and similar access to resources might have found ways to deal with problems that are in tune with our reality – and is a completely different reality to the solutions that our colleagues in Europe and the USA may propose. So I think strengthening South-South collaborations is very important.

Who are your scientific role models (both Ecuadorian and foreign)?

I think I have a lot. I mentioned Ruddy Raff, whose book has inspired to me and so many scientists. I also mentioned Peter and Rosemary Grant and their fabulous work on Darwin’s finches – they discovered evolution in action, through many decades of persistent work in the Galapagos. In every place I’ve been, I’ve met so many exceptional scientists that it feels unfair to have to list only a few of them here. As stated earlier, my undergraduate advisor Eugenia del Pino in Ecuador has been decisive for my career. Billie Swalla – my PhD advisor in the USA, was very influential – in addition to her great science trying to understand chordate evolution, she was very involved in closing gaps in terms of gender minorities, racial minorities and equity – she was very outspoken about this, and I learned a lot from her in this respect too. I completely believe that minorities in science should have a voice – and currently we aren’t quite there yet. In Germany, Ralf Summer was also a great mentor – he gave me a lot of freedom and support.By studying vulvas in nematodes and comparing these across species, his research revealed a phenomena known as developmental systems drift, an evolutionary process we are still trying to understand. I would not like to leave other people out: Lynn Riddiford at the University of Washington in Seattle – I did a rotation in her lab. She and her husband, Jim Truman, study development and metamorphosis in insects. This experience in her lab really opened my eyes to arthropods – powerful models to address different questions in the field of Evo-Devo. Richard Strathman from Harbor Friday

Laboratories is another great role model, not just for me but for many people. Besides his academic contributions in the field of Life History Theory, he is one of the most ethical scientists I have met, and one of the most generous – one of many examples is he doesn’t generally accept to be author in papers of his own students unless he has carried the work himself and can endorse all data and analytical methods, which is very rare nowadays as advisors have become less involved in their students data collection and analyses. He has traveled around the world teaching courses in larval biology, and whenever anyone needed help he was always available. He is truly unique not just as a scientist but as a human being.

In South America, I have met many admirable scientists. In Colombia, when I worked in the Department of Biology, I met Felipe Guhl and Helena Groot, who are two great scientists working on tropical diseases, human genetics, and biomedicine. Both had very successful careers and strong research groups, were always available to give valuable advice, and they tried to provide ways and inspiration to the younger faculty so that good science can be done. In Brazil there’s also some great senior faculty in my Department that have done amazing work and they have served as an inspiration to me and others. Eudoxia Froehlich and Miguel Trefaut Rodrigues have made enormous contributions to our understanding of flatworm (planarians) and herpetology (the study of amphibians and reptiles) diversity – their careers are a huge inspiration. Seeing all the senior faculty that have done a good and successful career in Latin America send the message to the junior faculty, that this is possible and achievable.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Ecuador, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

Gender balance is still an issue. This is something I realized after working with Billie Swalla for many years as a PhD student. When I studied in Ecuador, Biology was very well represented by fabulous women scientists. The Department of Biology was in fact headed by exceptional women scientists since its early formation dating back to the early 1970s, one of which inlcuded my undergrad advisor Eugenia del Pino.. Therefore, I had this view that women and men were equally engaged in doing great science and with similar opportunities. Only after Imoved to the USA and gender issues were regularly discussed in Billie’s lab that the real issue of gender imbalance in many fields of science became evident to me. I became aware that my experience in Ecuador was an exception to the rule. There are many issues with regards to gender balance. We still have to actively think and commit to keeping this balance in everything we do: the people who teach, the students we reach, the speakers we select at conferences, the people we recognize. It is embarrassing for me that my current Department (of Zoology) is incredibly male dominated. There is some affirmative action to be done, and a real effort to reach a 50:50 balance. In addition to gender balance, we should put an effort to achieve a better representation of minorities, including low socioeconomic status, race, LGBT+ and indigenous groups, all of which need to be better represented in science. Latin America is very diverse and opportunity inequalities are increasing, so I believe that we need to continue supporting affirmative actions at all levels until we can get a proper representation of social diversity in science and academia. In Ecuador, in Biology, the gender balance was healthy, but there are other fields where gender balance is poorly represented. I am a member of the Academy of Sciences in Ecuador, for instance, and it’s still heavily male-dominated. So in general, we need to put more efforts into achieving this balance.

Are there any historical events in Ecuador that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

There have been very big steps in science driven by very few people. Eugenia del Pino is an example of people who have managed to do extraordinarily creative and exciting research in a place where science overall is under-represented: without funding, without PhD programs, without postdocs – working only with undergraduate students. And these scientists have gained visibility around the world, and they have really pushed and driven local science forward. But I think this has not reached the institutional level. Historically it has been driven by single efforts, and not governments, institutions or programs driving these advances. This is in contrast to what we see in Brazil or in the USA, or Argentina. In Ecuador we really have to acknowledge the achievements and efforts of individual scientists. Most of them come back from working abroad, and are incentivising the younger generation to build science. Unfortunately, it’s very variable from government to government in Ecuador – a permanent policy on science does not exist. I hate to be more pessimistic than optimistic, but it’s what I see.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Ecuador?

Yes, I think everywhere. It’s not exactly easy to be a foreigner. When I was first abroad, I went to the USA. I was a bit saddened by the fact that the scholarships and funding you could get is restricted to USA nationals, and for minorities, but if you are a foreigner you can’t apply. This affected me and many foreigners in the USA. In Germany, I was in a very wealthy institute, where I had a lot of freedom and funding to develop my own ideas and skills. The Max Plank institute is also a hub for foreigners – there were more foreigners than Germans, so I really felt no issues with integration. In fact I wanted to interact with more Germans, and found it difficult. After some time I found a way to interact with them outside of the institute, and practice the German I had learned in school, and attend lectures in German and so on. Afterwards, I went to Colombia – Colombia has very few foreigners in science– mostly scientists who married Colombians and so moved there as a family. As a foreigner, the main problem (which is the same I faced in Brazil), is that when you come into these countries as a foreigner, and you don’t know the groups, it’s very difficult to get involved in collaborations initially. You first need to make yourself visible in these countries. But at the beginning you are left behind in these collaborations and group efforts. It takes some time to enter these closed circles. So this was a challenge. It’s different if you studied in the country, in which case you are almost by default included in the scientific community of the respective countries. This particular challenge is different in places where influx and mobility are more common, like in the USA, where changing institutions at each career stage is generally favored. Here in South America, it’s not so common, and the periods of adaptation take much longer.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

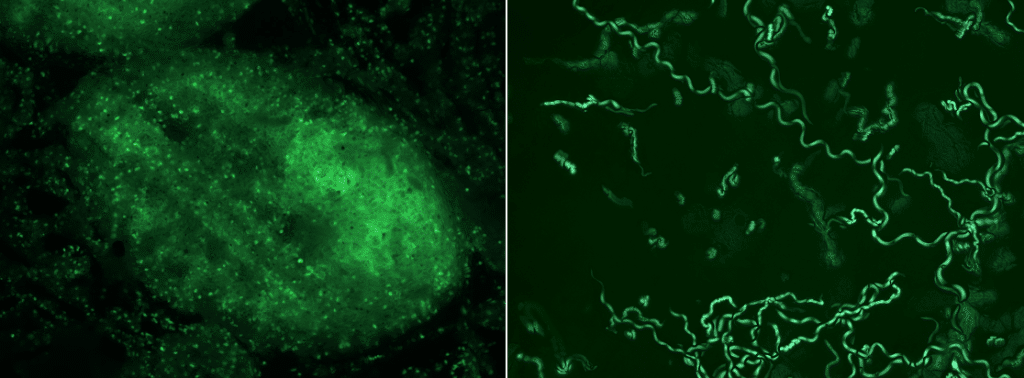

Microscopy for me has been a vital tools since I was an undergrad. I’ve been using microscopes since I was in Eugenia’s lab. I remember the first time I started using fluorescent markers to see different things in samples. Fluorescence in general is fascinating. I love confocal microscopy. We currently a Leica SPE in my laboratory for regularly use. The Center for Image Aquisition and Microscopy at our Institute (CAIMi-IBUSP) has other cutting edge confocal microscopes, such as a Leica STED 3X for super resolution, or a Zeiss LSM 880, in addition to several other microscopes for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In contrast to expensive microscopy services in other facilities that I have experienced abroad, microscopy use at the CAIMi-IBUSP remains quite affordable to researchers at our Institute and other researchers in the region. I would love to have a SPIM or light sheet for developmental biology for better visualization of our specimens and reduced photo-bleaching.

Since we study embryos and regeneration, we can do very fine cuts with the Zeiss PALM CombiSystem for laser micro-dissection, also in my laboratory. All these technologies allow us to manipulate animals and study developmental effects. So I guess those are the main ones I love.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

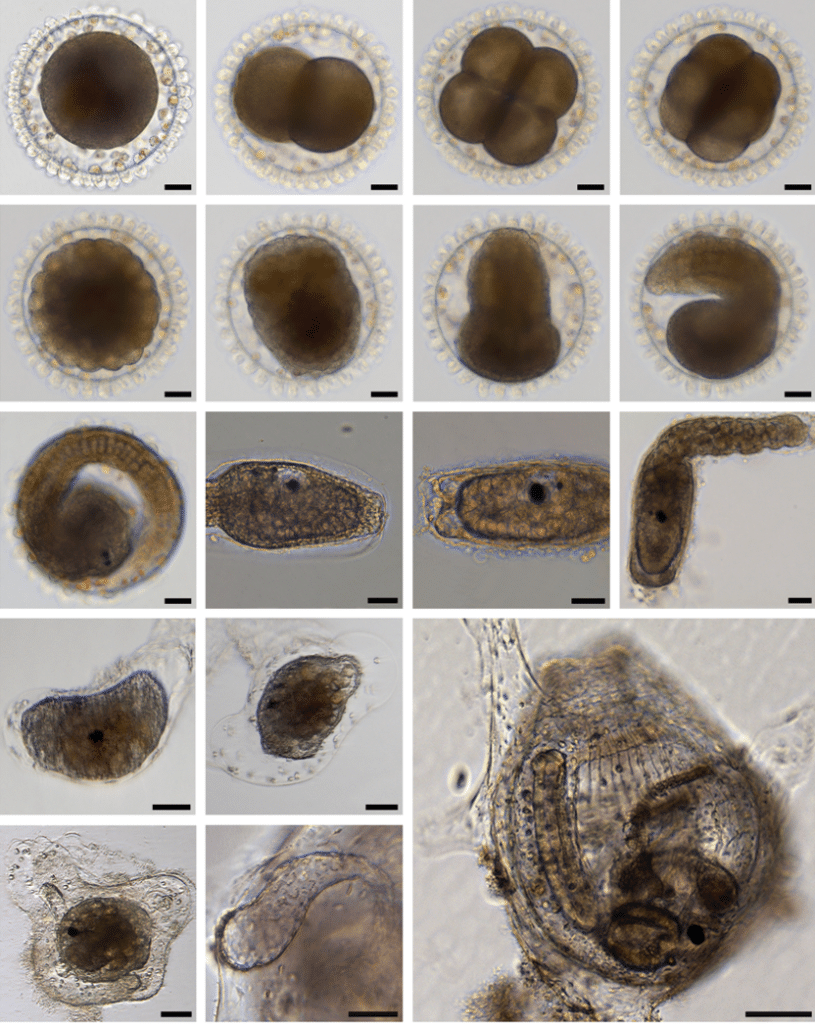

In Seattle I met fellow biophysicist colleague, Manuel Forero, who was doing his PhD at UW – he is Colombian. When I started my first faculty position in Colombia, he also returned as a faculty at Uniandes and was building his own SPIM (Light Sheet). He knew the some of the researchers that were developing the first SPIM in Germany. This was even before Zeiss started producing commercial light sheet microscopes. Back in the days, Manu built the first SPIM in Bogota, Colombia, which was probably also the first in South America. He invited me to see the progress of the SPIM being assembled piece by piece, little by little. It’s a relatively simple assembly. So for me it was something very special, to be able to see an instrument like this being assembled from scratch. Once it was ready, we started doing visualizations of nematodes and other organisms from my lab in it. It was extraordinary. Apart from this extraordinary experience in Bogotá, I also wanted to mention another extraordinary experience during my PhD at Friday Harbor Labs-UW, where I was fortunate to interact with great marine biologist and microscopist George von Dassow. During that period I witnessed some amazing imaging of marine embryo development that George was producing, and that revealed some of the most divergent forms of cleavage patterns that you can imagine. Many of these live imaging time-lapse videos that George and others produced are freely available in this link, and are a great resource for teaching and for microscopy imaging enthusiasts. Some of those cleaving embryos are out of this world! Check out the “Time-Lapse Movies” in the gallery.

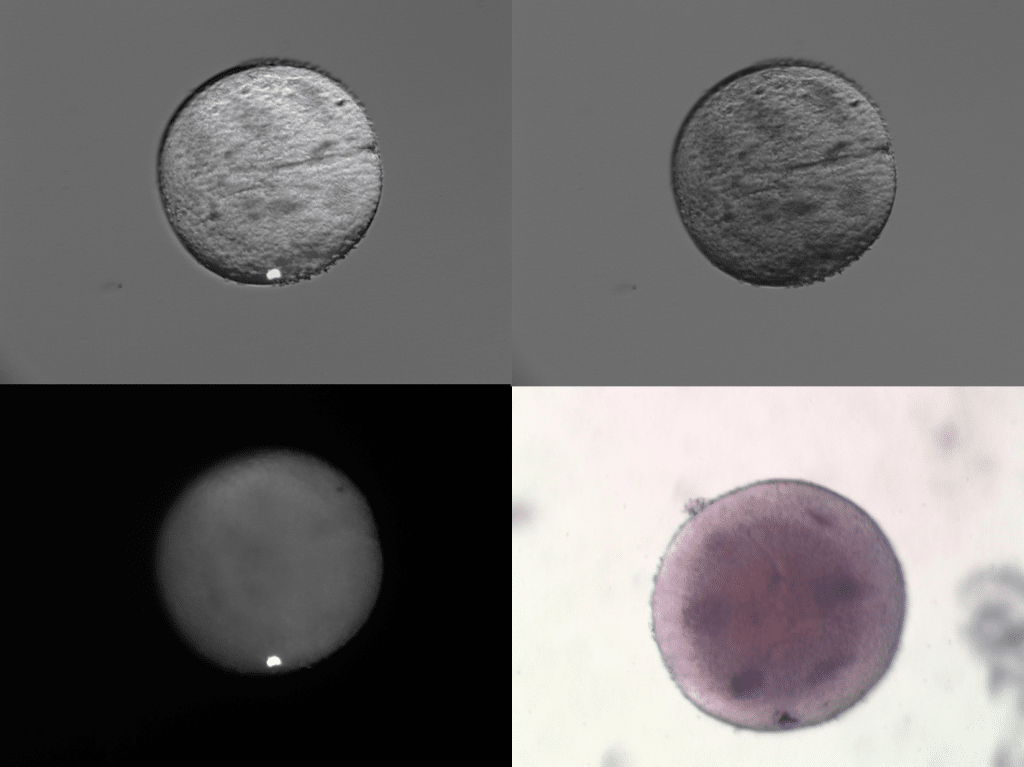

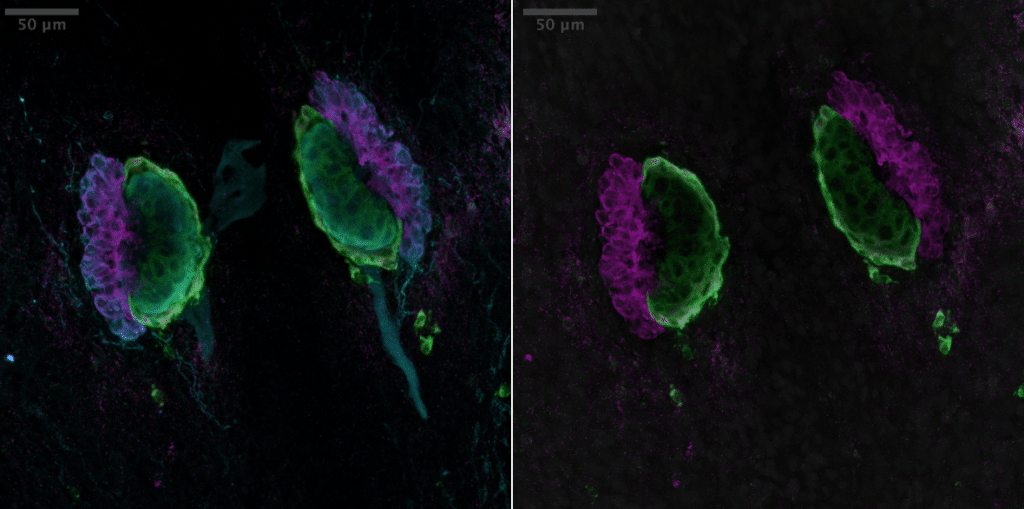

A Eureka moment occurred while I was doing my last set of experiments of my PhD in the De Tomaso Lab at Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey, CA. With help from former postdoc Stefano Tiozzo (now at LSDB-IMEV, France), I carried the first fluorescent in situ hybridization protocol for colonial ascidian embryos to observe the expression of germline marker Vasa in the PGCs of early cleavage embryos (see link). Because of their ability to bud (asexually reproduce) and regenerate as adult colonies, we did not expect a germline to be segregated early in embryogenesis. These results contradicted postulates of August Weismann’s germ plasm theory of heredity published over a hundred years ago.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Ecuadorian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

For embryology you need microscopes. You really need to learn how to use microscopes very well, from the very beginning. So, as a piece of advice, students should not only focus on the animal or organism that they are visualizing, but also think about how the microscope is built, how to get the best optics from the microscopes you have. It’s very important to learn how to use the filters, the diaphragm – how to build the best optics. Give value to the time you spend at the microscope. Not everybody gets to see the microscopic world with their eyes. Wonder, be curious, feel fortunate. Back in 2012, I gave a class in San Pedro, Province of Santa Elena, Ecuador, a small town where the Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL) has a Marine Center (CENAIM), and they did not have enough microscopes for my course. They had only one functioning stereoscope and I needed at least 15 for the students of the course. So we started traveling to every university around, to have them lend us their stereoscopes. In the end we borrowed 8 additional microscopes. We received students at the course that travelled from different universities in Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile, and many of them were observing marine embryos for the very first time. This was a life changing experience for many of them, a gateway to the microscopic world. Look for these opportunities in which microscopes are available, and value the time you spend at the microscope. Foldscopes, as mentioned earlier, may also open this opportunity for the general population. Those are the main pieces of advice I can think of.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Ecuador, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think Ecuador still needs major investment, but not only in infrastructure. In the last few years, institutions in main cities like Quito and Guayaquil, have improved their resources: now you can have access to EM, confocals, etc. The problem is oftentimes there are no technicians or imaging experts that can either use the microscopes or maintain them. This should be corrected – there should be positions exclusively dedicated to providing assistance at the microscopes. In terms of scientific progress, Ecuador has huge potential to generate novel findings and original ideas because of our geographic location – with the Andes, the rainforests, the coasts and the Galapagos, and its great biodiversity. Ecuador values a lot its resources, and microscopy can contribute a lot to major findings there: microorganisms in the extensively diverse cloud and lowland rainforests, other microorganisms living adapted to altitude or other extreme environments. Galapagos diversity is fascinating and high in endemism – how different isolated microenvironments have favoured and influenced the unique biology in the region. I think that’s the future: the strength of using unique models to answer complex questions in a highy diverse region such as Ecuador will bring about very novel findings.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Ecuador a special place?

It’s my home! Ecuador is a fabulous place to do biology and microscopy – for its life, its diversity, its geography. Nature is the most fascinating resource here, making Ecuador a place for discovery. Plus, if you consider the ethnic diversity, we have many languages for such a small place. Brazil is also very diverse, but over a much larger land-mass. To travel to a different ecosystem you have to travel days. In Ecuador, in a single day you can go from the Pacific coast, to 6000 m on the Andes and down to the Amazon rainforest. So it’s a small area, but very diverse.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)