I heard a vicious rumour. At dinner recently, an American couple seated at an adjacent table, having engaged a friend and me in conversation, revealed that they used to eat at l’Arpège, but that was before the chef became a vegetarian.

It was a shocking comment. We were aghast.

In hindsight, however, such statements should not have surprised us; Alain Passard and l’Arpège are two of the least widely known and most misunderstood names in Paris. Furthermore, when either’s mention does elicit a glimmer of recognition it is either for the fact that l’Arpège is the city’s (and so a contender for the world’s) most expensive restaurant or verily for Passard’s vegetarianism. Both of which are incorrect.

It is important to address and redress the most misleading and most influential of these two assertions in more detail – the second. Passard is definitely not a vegetarian and, ironically enough, does not even like the term; he feels that the ‘real malady and unhappiness of vegetables has always been the vegetarian restaurant’. Instead, the chef is a patron and, indeed, prophet of la cuisine légumière.

In January 2001, Alain Passard made the headlines, having declared that ‘my menu will be entirely and exclusively dedicated to vegetables’. His decision was motivated mainly by personal choice, but in part by health concerns too (mad cow disease had reached France the previous year). The chef, having spent thirty years establishing himself as a maître rôtisseur, admitted that he ‘didn’t take any pleasure any more in eating meat’ and that ‘blood and animal flesh’ had stopped being a source of inspiration. The situation became so serious that Passard spent an entire year away from his kitchen, only setting foot in the restaurant to eat. ‘I no longer wanted to be in a daily relationship with the corpse of an animal. I had a moment when I took a roast out into the dining room and the reality struck me that every day I was struggling to have a creative relationship with a corpse, a dead animal. And I could feel inside me the weight and the sadness of the cuisine animale.’

Vegetables were his salvation. He needed new motivation and found it by replacing the raw materials with which he moiled, ‘like an artist who works in watercolours and turns his hand to oils or a sculptor in wood who changes to bronze’. The colours, flavours and perfumes of greens, herbs and flowers appealed to and stimulated him; more to the point, they changed his life. ‘All the terrible nervousness and bad temper that are so much part of the burden of being a chef were gone with the old cooking. I entered into a new relation to my art, but also to my life. And the lightness of what I was doing began to enter my body and my entire existence and it entered into the existence of the kitchen. It was like a light that I saw and a door that I walked through’.

Passard recognised this new vegetable-focused cooking as his ‘renaissance as a chef’ and, to return the favour, he wanted to dedicate himself and his skills to their elevation. However, his consequent, aforesaid abandonment of red meat and its replacement with green veg, was met with scepticism and cynicism: ‘you are offending your colleagues who are still cooking meat’, claimed a caller during a radio interview; ‘is this not an act of blatant opportunism at a time when French farmers and butchers are suffering?’, demanded reporters; contemporaries feared for him; Paul Bocuse professed he was uncertain how Passard would fare, but conceded that ‘perhaps he [could] succeed – that boy certainly has a lot of talent’. Michelin suggested that it was a courageous strategy while he himself realised, ‘I am putting all the cards on the table. Putting myself and my entire career in question. My three stars, the public, my clients’.

Not one for half-measures or hollow gestures, having staked his livelihood on légumes, he dedicated his leisure to them too. In 2002, he bought the Château du Gros Chesnay, in Fillé-sur-Sarthe, about two-hundred kilometres from Paris, near Le Mans, sharing the property with the previous owner, Madame Baccarach, who minds the house whilst the chef visits the two hectare garden each weekend, employing three gardeners to tend to it fulltime. Using only natural fertilisers, non-mechanical tools (like horse-drawn ploughs), a rotating small-plot system and pesticides made exclusively of vegetable extracts, this organic potager is a ‘showpiece of permaculture’; there is even a purpose-built lake on the grounds and four bee-hives to help maintain a balanced ecosystem (and provide l’Arpège with its very own honey). In his pursuit of grand cru greens, Passard is in constant contact with horticulturists, farmers and gardeners whilst also reviving heirloom varieties of various vegetables (including thirteen sorts of asparagus). The garden contains one-hundred-and-fifty different breeds of plant and supplies eight to ten tons of produce per year – nearly all that the restaurant requires. The crops can be picked at seven in the morning, in time for the ten o’clock TGV to Paris; no refrigeration is necessary and transport times are short – therefore the légumes lose very little of their freshness and flavour – and thus, that morning’s bounty is able to become that afternoon’s lunch. What l’Arpège does not consume is sold on a small counter at la Grande Épicerie du Bon Marché and any kitchen waste is returned to the garden for use as compost. The project’s success has led to the addition of two new farms at Buis sur Darnville and at Baie du Mont-Saint-Michel; the chef can now call on a team of twelve farmers to cultivate a sum of six hectares. His mission, he says, is to encourage people ‘to talk about the carrot the way a sommelier talks about Chardonnay’.

As alluded to earlier, Passard’s repute was primarily built upon a talent for roasting meat and poultry. This he learnt from Louise Passard, his grandmother and also his teacher. It was through her that he developed not only an understanding of how to cook – and form a relationship with the flame – but also how to host and prepare a meal: ‘they’re all her recipes. She gave me everything, taught me what to look for when I made my first purchases, taught me the right cooking times and temperatures.’ Around the hearth, they spoke of the fire and its ability to sculpt the product; the importance of watching and listening to it; and the sensitivity of a cook.

His parents, a musician and dressmaker, lived in La Guerche, Brittany, and their neighbour, the village’s pastry chef, was Passard’s second inspiration. At the tender age of ten, he began to train with him, discovering the ‘rhythm and activity of the laboratory and the evocative qualities of aromas’. At fourteen, he became an apprentice cook at Hotel du Lion d’Or, Liffré under Breton star, Michel Kéréver, learning la cuisine classique and the appreciation of good products. Four years later, he moved to la Chaumière, Reims to work with Gaston Boyer, furthering his classical education whilst studying the art of seasoning and cooking. In 1977, he joined Alain Senderens’ l’Archestrate and enjoyed the most instrumental period of his career. Under Senderens, ‘a perfectionist in constant search of originality’, he discovered his creativity and the power of imagination; it was a ‘baptism of fire’ cooking in a small kitchen, but with a tight team and exceptional atmosphere. Here, he expanded his repertoire of and improved his touch with spices (and possibly picked up his cigar habit too). After three years, he took the reins at le Duc d’Enghien in the northern Parisian suburb of Enghien-les-Bains. Within two years, he had earned two Michelin stars and, not yet twenty-six, became the youngest chef to have ever achieved such a feat. It was during the four years spent at this restaurant that he conceived some of his classics including carpaccio de langoustines and le chaud-froid d’œuf à la ciboulette (the possible precursor to the infamous l’Arpège egg). The next two years saw the chef at le Carlton, Brussels, were he was once more awarded a first and second star successively in that short time. It was not until October 1986, however, that Passard was able to proclaim, ‘je suis chez moi’. Senderens had moved to Lucas Carton and Passard had moved into his mentor’s old home, l’Archestrate. By March of 1998, history repeated itself, a second time, and the newly-named l’Arpège had been visited twice by Michelin within two years; although the chef had to wait eight more, until 1996, to finally win his elusive third star.

For the last twenty years, Passard has devoted his time and efforts to l’Arpège and its success, limiting himself to just a select number of outside business interests that include co-producing moutarde d’Orléans with Jean-François Martin, collaborating with Chrisofle on a line of vegetable-orientated crockery, selling the restaurant’s bread recipe to bakers and writing, with Antoon Krings, a children’s cookbook, « Les Recettes des Drôles de Petites Bêtes ». He also participated in Japan’s Iron Chef competition between 1997 and 1999, where he won considerable acclaim.

Alain Passard’s unique combination of controversy and accomplishment even prompted French business school, INSEAD, to conduct a case study with him as its subject. ‘[He] is a fascinating example of someone who has succeeded by being both highly creative and very efficient in management terms. Much of what [he] has done breaks the rules,’ revealed one professor. The analysis showed that although small in size, located in the ‘culinary desert’ of the 7e, refusing to offer valet parking, eschewing celebrity status and playing down branding, he has not only disproved detractors that expected him to lose his third star, but prospered, created his own supply chain and set himself up as a paradigm for peers.

The l’Arpège appellation immediately lets slip plenty about Passard. The chef chose it above all as a tribute to his musician father (arpège being French for arpeggio), but whilst also bearing in mind that selecting a name beginning with A would cunningly allow him to keep the former resident’s monogrammed crockery.

The restaurant itself resides near the prime minister’s offices and government ministries, on a quiet street, opposite the Musée Rodin. Without, it is non-descript and unadorned save some flowery script that spells out l’Arpège, but within, the dining room is warm and comfortable. Rich browns and earthy oranges dominate; pear wood panels line the interior; and a dog-eared, burgundy carpet covers the floor. Music is Passard’s second love and the melodious insinuation suggested in the restaurant’s title is maintained by the motif inside: handmade Lalique pâtes de verre, inspired by the carriages of the Orient Express and inset along the far wall, depict Pan playing the flute whilst frolicking with two naked nymphs (images mimicked on menu covers); an abstract split cello sculpture by Arman sits in one corner; a coarsely-carved wooden guitar grows out the serving station; and, upon Bernard Pictet windows, etched waves ripple. This undulating design is also incorporated into Jean-Christophe Plantrou’s peau de poirier panelling and Massacar ebony furniture pieces. Rich, red leather upholstered chrome seats and chariots as well as the various bucolic bibelots such as large desiccated gourds or little twig bundles that rest upon tables, play on art déco principles. The only presence on the room’s walls is the nineteen-thirties/forties portrait of Louise Passard, which watches over the ‘chef’s chair’. White linen tabletops are dressed with bright red cover plates, Bernaudaud crockery, Christofle cutlery and customised glassware inscribed ‘Fabrique pour Alain Passard’.

This was my third visit to the restaurant and, as I had not ordered from, let alone held, the l’Arpège menu on the previous two, I decided not to break what was fast becoming a rewarding habit. My second time here had only been two weeks ago, when Aaron, his brother and I had enjoyed an excellent meal (highlights included damier de radis pastèque et coquilles Saint-Jacques d’Erquy; huile de noisette and couteau avec poireau, échalote et ail), so Hélène Cousin, maîtresse d’hôtel, was already aware of my preferences and offered that the chef arrange something. For the record, none of the dishes from the previous occasion, besides the signature egg and one other, were repeated.

Amuse Bouche 1: les Tartelettes – Mousseline de betterave et vinaigre balsamique; et mousseline de poire avec carotte jaune et praliné de noisette. To tease the taste buds, a quartet of tartlets in two varieties arrived. Two pastry cup couples, symmetrically similar but constructed with contrasting components, carried the classic pairing of beetroot and balsamic vinegar and the less common one of pear, carrot and hazelnut. The former, formed with a mound of beet mousseline mounted by a smaller disc of albina vereduna (white beetroot) topped with a drop of balsamic, was sugary and earthy with a touch of sharpness. The latter, with pear mousse, yellow carrot chip and hazelnut nugget, was sweet, herby and nutty.

Le Pain et Beurre: Pain de campagne; le Beurre Bordier. Excellent, thick slices of slightly warm, slightly sour, homemade country bread, with an open crumb, had rustic crunch, soft, fluffy centre and nice seasoning. As toothsome as this was though, the beurre de baratte – from Jean-Yves Bordier of St. Malo – was simply terrific, actually it is the best butter I have ever had. Sculpted into a semi-circle and standing on one side (Bordier has a customised shape for each restaurant he supplies), it was creamy, spreadable and saturated with sel de Guérande, the hand-harvested sea salt considered the finest in the world. This butter is addictive.

Amuse Bouche 2: Oeuf à la coque; quatre épices. An egg from the ferme de Bigottière in the eponymous little village of the Loire, diligently decapitated and its white drained off to leave only the unbroken yolk within its shell, was simmered in a water bath until just before the yellow could set; it was then sprinkled with chives and quatre épices prior to the addition of a little crème fraîche with aged Jerez vinegar, smidgen of Canadian maple syrup and fleur de sel to finish. There was a deft drama here; the first, ginger, shallow spoonful was sour and pungent owing to the fresh cream and spices, but once one had summed up the courage to plunge down into the egg fully, bursting the yellow and allowing it to blend with and bind all the elements altogether, the taste was transformed. The warm, runny yolk itself was intense, but balanced by the whipped cream, light and barely bitter, with aid of the sherry vinegar’s acidity, whilst together, the two soothed the syrup’s deep, smoky sweetness as the four spices – clove, nutmeg, white pepper and ginger – added aroma and exaggerated the flavours already there with their own sharp, bittersweet woodiness.

This signature, humbly presented in an elegant, but basic, silver egg-holder sat upon two plain, porcelain plates, a smaller superimposed upon a larger and each unadorned except for a thin, red rim, is an archetypal amuse: it has harmonious yet exciting savour; simplicity and complexity; contrasts and variation in texture and taste; the demonstration of technique, humour and creativity; an arresting dynamism; as well as of course quality ingredients. More to the point, it awoke and provoked the palate.

Entrée 1: Bouquet de turbot de Bretagne au miel du jardin « récolte été 2008 »; vinaigre de Xérès. Bréton turbot, grilled then cooled and swimming in a sticky sauce of honey infused with peanut oil and lime, had been blanketed with four wafer-thin, cross-sections of black radish, then freshly peppered at the table with more of the sauce making a bucolic boundary around the bouquet. The initial taste of the honey, harvested the previous summer in Passard’s own organic garden, was delicious – strong, sweet, zingy, tart and nearly nutty, this was a heady and complex combination. The firm slices of radish, still crisp, offered a hint of heat and textural distinction. Moist yet firm turbot had great flavour, its delicate marine sweetness complimented and countered simultaneously by the aigre-doux sauce, whose nicely viscous nature meant it coated each meaty morsel pleasingly. Pepper provided another individual accent.

Entrée 2: Parmentier des légumes du jardinier. Presented in matching manner to the Arpège egg – starkly but assuredly in an alabaster ramekin atop two concentric plates – a potted pie came with an enticingly crumbly, rusty gamboge crust of semolina and crushed black pepper. The cuillère, penetrating its cover, uncovered a thick, pale gold vegetable purée composed of parsnip, beetroot and radish; further excavation exposed a narrower, darker foundation of confit chestnut and oignon doux de cévennes. Airy, light and earthy-sweet, the upper layer was like whipped cream. Beneath this, the melted down chestnut and sweet cévennes onions, were much sweeter and had a stringy yet more unctuous consistency. This was clearly a witty makeover of traditional hachis parmentier or shepherd’s pie – basically, mashed potato over minced meat and onions – but missing the meat.

Entrée 3: Gnocchis multicolores; quaternaire au beurre noisette. A quaternary of colourful, chubby gnocchi of beetroot, smoked parsnip and parsnip pair, were presented resting in Bordier beurre noisette and garnished with Parmigiano-Reggiano and sage. A lovely, herby odour emanated from the dish. The beetroot pasta was like a thick pâté of well-balanced sugary-earthiness. The parsnip trio was lighter and grainer, each dissolving on the tongue. The smoked example was just that while the plain parsnip twosome had delicate vegetal-sugariness. The butter sauce was obviously delicious; parmesan had a touch of sharpness and depth; and musky sage, a faint spiciness.

Entrée 4: Cerfeuil à l’huître de l’archipel de Chausey; truffe noire de Périgord. A single shelled oyster Marenne d’Oléron, in almost alternating shades of grey and copper, came casually bound with bow-tied string and sitting on a dune of coarse sel de Guérande. Visual senses surfeit, the loop was loosened and lid lifted to disclose an oyster that had been shucked, replaced and then poached in olive oil, before being dressed with a slice of black truffle and sprigs of lacy chervil. A fresh whiff of the sea immediately impressed. The sizeable and succulent shellfish’s savour was sweet and salty with clean, short linger; it also had a faint nutty note that was in quiet concord with the fainter truffle whilst the chervil added herby freshness.

Entrée 5: Sushi légumiers à la moutarde d’Orléans oncteuse; turbot de Bretagne et d’écrevisses. Resting amidst marjoram leaves, its long stems and dainty drizzles of olive oil and balsamic vinegar, two rice-paper-wrapped packages of cauliflower, black radish and regular radish julienne, seasoned with a midge of Orléans mustard, were crowned with turbot and crayfish respectively. Each bundle boasted crunchy, peppery, earthy vegetables gently spiced. Both specimens had distinct, fine flavour; the mustard coming through especially with the turbot piece. Vinegar livened up the plate with its sugary acidity as did the marjoram’s subtle citrus. The savours were pure and delicious, light and refreshing.

Entrée 6: Fines ravioles potagères; consommé végétal. Next it was a quintet of ravioles, each with a wrinkled skin wrapping various finely-diced vegetable fillings, floating in a translucent, saffron-shaded consommé of celery root. The soup within which these wonton-like parcels were submerged was refreshing, precise and pure. Ravioles, common to the Drôme and Isère, were created when Italian loggers from Piémont, adapting their traditional meat-filled ravioli to their new, more limited means, crafted smaller pastas from turnip sheets that they stuffed with vegetables or fresh cheese. Now customarily eaten at Easter, when meat is forbidden, Passard applies an Eastern twist to the dish, serving them in a clear vegetal broth. All had thin, almost see-through casings that melted in the mouth. The rendering of black radish with horseradish had mustardy, sweet heat; chestnut, crumby, sweet earthiness; the celery was light and crunchy; endive, perky; and cabbage, crisp and mild.

Entrée 7: Tagliatelles de céleri-rave et risotto à la truffe noire; herbes fines. Filigree-like, thick threads of counterfeit tagliatelle, actually composed of celeriac, were surrounded by a shallow emulsion of moutarde d’Orléans and stippled with parmesan and fines herbes. For the first time today, I was served something I had already tried the previous week, so I decided to tease Hélène about it, pointing out to her this was a repeated dish and, not only that, but before it had come with black truffle. She took it in good humour, but returned moments later. Not empty handed. A bowl of parmesan risotto replete with truffle was set besides my plate of pretend pasta.

Al dente root ribbons yielded subtly to bite, but still had satisfying crunch; their gentle nuttiness hit a note with the strong parmesan. The Orléans mustard sauce was frothy yet forthright with agreeable spiciness. This condiment is manufactured from a medieval recipe, which Passard and Jean-François Martin, an Orléans vinegar-maker, have saved from disappearance. It consists of mustard seed, sel de Guérande, Martin-Pouret vinegar, honey and Chadonnay and is made by traditional, machine-less methods.

The risotto was reminiscent of savoury rice pudding; it was extremely creamy with a very slight sweetness. The truffle, with its full fungal fragrance and effect, was in harmony with the rich hazelnut and olive oil dressing whilst the ivory Arborio grains melted away immediately upon ingestion.

Entrée 8: Betterave en croûte de sel gris de Guérande; vinaigre balsamique. From a whole golden beetroot – albina vereduna – that had been baked in a crust of sel de Guérande, broken out then carved, a solitary quarter was dished upon a dribble of twelve-year old balsamic vinegar. This was so simple and superbly subtle yet so confident and utterly emphatic. The supple centre of the succulent, sweet beet had been coarsely, though consummately, cut from its saltier, earthier skin, within which it was now cradled. The conflicting intrinsic character of the ingredient itself, the silky lustre of its soft flesh in stark comparison to its rough, harsh rind, was masterfully manipulated. Such internecine distinction was sharpened and cultivated with the addition of the acidic, fruity sweet, aged vinegar that loitered on the tongue.

I cursed my luck in between this course and the next as the day’s ‘special’ was wheeled out and showed off to the crowded room. There was seated, on a shiny silver chariot and atop a considerable silver serving platter, côte de porc in sea salt crust with its coral-like crackling glistening. An entire rack of pork, none of which I could have….

Shortly after the pig’s pageant, Passard sneaked out the kitchen. Dressed in customary colourful neckerchief and denim jeans under his chef’s whites, he greeted his guests.

Entrée 9: Brioche de légumes à la moutarde d’Orléans onctueuse; ouef de caille. Toasted, buttered brioche bearing a plump, terra cotta coloured patty of chopped legumes – beetroot, radish and turnip – was topped with parmesan and finished with fried quail egg; alongside lay a careful squirt of beetroot mousse. The warmth of the vegetables had begun melting the cheese whilst the egg, as if its yolk were pricked on purpose just before presentation, started to dribble over this cheeky, bogus burger to which the beet purée played the ketchup. The melange of veg had a pasty, thick texture and peppery, savoury relish. The unctuous, toothsome quail egg, creamier than that of hen, was cut through by the light but tartly-sweet beetroot.

Plat Principal: Coquilles Saint-Jacques d’Erquy à l’unilatérale; chou et thé vert « Ashikubo Sencha ». Prepared à la plancha, a pair of scallops from Brittany, still attached to their shells, were interlaid with draping leaves of cabbage, steeped in Ashikubo Sencha, and thin cross-sections of shinrimei; the chou’s matcha sauce was also mizzled over the shellfish. This was a feast for the eyes and I allowed mine to enjoy it: shellfish and cabbage in matching shades of creamy white, and radishes, with starburst magenta middles and dark emerald edges, all smeared with a gentle green that collected in pastel puddles around each Saint-Jacques, in the shallow impression of their particular shuck, which themselves, both alabaster at large, were adumbrated mahogany before burnt umber towards their tips. Erquy scallops, arguably the finest France has to offer, were fat and well-flavoured, but I admit I would have preferred them a touch less done, although they were evenly cooked and still dissembled willingly in the mouth. Excellent cabbage that had bite to it was coated in thick tea that nicely and fully infused the leaves; the attractive radish, an heirloom variety of daikon, was mildly sweet with a pinch of pepperiness. The sauce of premium sencha, dried in the traditional way with wood fire, was complex and interesting. It was distinct and definite, but muted with a very mellow, woody astringency, faint vegetal-grassiness and subtle bittersweetness. Its consistency – fluid yet with a dense, almost starchy aftertaste – also intrigued.

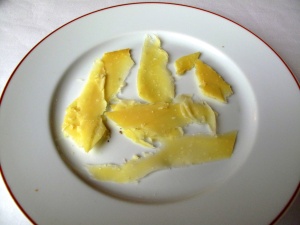

Le Fromage: Comté de Garde Exceptionnelle september 2004; Bernard Antony. Alsatian maître affineur, Bernard Anthony’s famous four-year old comté, freshly shaved from the huge muele that is wheeled about the room on its own petrified wood tray and chariot, was a must. This is, in my opinion, the world’s greatest cheese. Anthony, first discovered by Alain Ducasse, started aging cheeses in 1982, after meeting Paris’ most eminent affineur of the day, Pierre Androuët who encouraged him to set up his own cave in Vieux-Ferrette. Today he has four and simply refuses to purvey his wares to anyone but the best; this comté is his masterpiece. Intensely yellow, aromatic wafers come riddled with crystals that effervesce with concentrated cheese essence. Creamy yet dry, they evaporate on the tongue, exploding with strong flavour that lingers long on the palate. I have never found anything quite like it. Delicious.

Dessert 1: Millefeuille « caprice d’enfant ». A capricious construct, composed of thick, thin, then thick again, rusty tiers of pâte feuilletée caramélisée, each punctuated by bold, brimming billows of crème pâtissière noisette, came crowned with a final few sheets of pastry powdered with icing sugar. Served without any accompaniment, naked in the centre of an empty plate, this dessert exuded confidence; impressing with both its munificent measure and its complete physical dominance of the dish. Incredibly crispy, light and flaky, each bite broke the pastry into a thousand tasty fragments. The subtle, creamy mousse, like praline chantilly, was rich without being heavy. Each mouthful of millefeuille overwhelmed with a wealth of textures and sweet, nutty savours.

At this point, Hélène wandered over once more, ‘so, how is it going? Have you enjoyed your meal?’ Stretched out and slouching in my chair, my Cheshire cat grin was sufficient affirmation for her. ‘If there is any room,’ she began, but I had already sat up and started nodding, ‘mais bien sûr!’ ‘In that case, I think there is something in the kitchen…’ She was out of sight for but briefly, before returning with the following.

Dessert 2: Île flottante moka-mélisse; caramel au lait. A stout yet shapely couple of coffee sorbet quenelles, buoyant on bright yellow lemon balm crème anglaise, were laced with lashings of caramel syrup. The sorbet, which were substituted for customary meringue in this île flottante, had the most interesting texture; ice cold, astonishingly airy, ready to dissolve in the warmth of the mouth and with an almost fizzy vibrancy. The roasted smokiness of the coffee was distinct, but the strength, well-judged; lemon balm custard bath had an exotic sweet spiciness that teased the palate; whilst the caramel au lait had a light, honeyed richness.

Petit Fours: Sucerie; 3 macarons du jardin. Presented upon a small linen-layered sterling tray, petit fours comprised palmiers à la badiane, nougats aux betteraves, petite tartes aux pommes and macarons of beetroot, coffee-parsnip and apple. Heart-shaped, baked puff pastry were crunchy, grainy and tasted of dark, sugary liquorice. Surprisingly nice beet nougat had very strong, even earthy, nuttiness. The assortment of macarons were good; apple had big, saccharine acidity; beetroot was clear, complex and full-flavoured; and coffee-parsnip had vegetal sweetness and mild, maybe too much so, mocha essence.

In my experience, which has been solely under Hélène Cousin’s stewardship, the service here has always been superb. As maîtresse d’hôtel, she is charming and welcoming, engaging and obliging. In addition, it is evident that she is an effective and efficient task-master, running a proficient, professional and tight team that seem always on the move, but always there when needed. Nadia, her able lieutenant, is persistently more helpful and knowledgable than expected whilst showing a touching recollection for one’s likes/dislikes. Friendly, well-informed and genuinely considerate, Sylvestre and Dav, who also looked after me, were also excellent. It might be argued that the fact that the front-of-house is directed by a feminine hand means that there is a grace and consideration to service that escapes some more macho establishments. Another attribute of l’Arpège’s staff that I find especially endearing is their generosity; the diner’s pleasure is of paramount concern with meals more often that not customised to suit palate and pocket. One can also sense a mutual pride amongst them for their chef’s creations, patent by the wish that the guest shares this fondness and embodied by efforts to that end.

Today’s meal was creative, satisfying and delicious. Each course pleased and teased, from the customary tarts, egg and brilliant bread and butter through to desserts. Bouquet de turbot tantalised the taste buds; the parmentier was as indulgent a vegetable dish as I could imagine; whilst the gnocchi were very good. The poached oyster and the sushi were a sight to behold and received with tremendous excitement, but the fact that the coquilles Saint-Jacques were cooked a little more than I prefer is the only detail that prevents me declaring this experience as technically faultless. l’Arpège’s comté is quite simply the greatest cheese I have ever had while the millefeuille was a very tasty treat and very messy fun to eat.

I must confess Passard’s cooking leaves an immensely moving impression on me; I struggle to name another chef – except possibly Bernaud Pacaud, albeit in an utterly different, almost opposite manner – whose food I find even as emotive as his. It is, as it is with all things sentimental, difficult to qualify and even more to articulate how or why. But I will naively try.

The food appeals to all and every sense.

First, there is the visual and at l’Arpège there is a raw aesthetic I have never seen matched. The chef’s artistic esprit is expressed acutely through impeccable elements, minimalist in number maybe, but full in colour and vitality. Passard believe in the single perfect gesture and this faith has great effect. Presented upon red-rimmed, bright white plates, golden yellows, pastel greens, vivid oranges and rich burgundies dot, splash or pepper a blank canvas, always leaving exposed some immaculate ivory, with which, the contents’ chromatic contrast creates a stark and bold reaction. There is almost an austerity and gravitas in this distinction and juxtaposition between dish and food – white against colour, empty against filled, crockery against contents – that has the potential to shock as much as it does intrigue and excite the diner and their fantasy.

There have been several moments when I have been left at a loss for words by the very serving and sight of a course. From my first meal, it was the epinards palco fanés au beurre noisette; carotte à l’orange. To some this dish of just a few strands of spinach, quenelle of carrot mousseline and smidge of lemon confit would have been enough to warrant complaint and criticism for its superficial simplicity, but it arrested my attention from first bite to last and left me speechless, or at least refusing to speak. Today, it was the huître poché; truffe noire de Périgord et cerfeuil, followed in swift succession by the sushi légumiers à la moutarde d’Orléans oncteuse. Both were unpredicted – never having received nor even seen or read of oysters in any form and anything so essentially exotic being served here before – and both were stunning. The former, a single unadulterated shell, stringed together, sitting on a small stack of sea salt in imitation of its native ecology, almost brutally beautiful in its pure and primitive, streaked shades of white, grey, blue and brown; whilst the latter, like a plate of little creatures, alive and crawling through sylvan-esque leaves, stirred me with avidity and interest.

Secondly, it is one’s imagination and intellect that are satiated. This aim is achieved with the use of humour, boldness, wit, suspense and surprise. To start with the last of these tools first, on a fundamental level and a personal one, remembering that I have always favoured letting the house serve me what it wishes, my overall enjoyment has been heightened by not knowing what dish or in fact how many dishes will come.

Then there is Passard’s panache and flair, his creative and culinary genius to contend with. This is most keenly felt via his valuable vegetables. The meat main course as the culinary climax to a meal is a custom few chefs refuse to follow. Here, however, regular viande rouge is not an option, but though this may be the case, no red meat is no loss and its presence is never missed. Instead, the chef capitalises on diners’ acculturation to or expectations of a meaty acme with the at times subtle, sometimes startling, but always effective substitution of vegetables for flesh. Examples of this abound from today alone. The brioche de légumes was its most blatant display, but there was the parmentier as well, which although traditionally made with beef, was improved here with mixed roots. Consider the infamous betterave en croûte too; arriving buried and baked within a firm saline skin, like a rack of lamb has for centuries been, as the salty crust is broken open, a single, basic beet manifests itself in mild mockery of its muscly predecessor. Then, as the meal nears its end, a sharp Laguiole– the generic haute gastronomic gesture that the meat is coming – is set down, but instead, the diner’s brainwashing becomes the butt of toothsome tomfoolery and the finest cheese or a surprisingly classic dessert appears. The fun does not stop there. Merely eliminating meat from the menu or showing flesh to be frivolous is not sufficient; Passard seeks to prove that vegetables can be great and, to do this, he strives to show that they can also be enough. Thus, after remaking such meaty recipes, he turns to carbohydrates, revealing rice and pasta as passé: celeriac is cut into thick strands of tagliatelle; risottos are replicated with grains of graven radish; and potato (technically still a starch, but in the ground at least) is reproduced as thin, loose strings of spaghetti.

Thirdly – and bear in mind, one has not even had a taste yet – it is one’s sense of smell that is seduced. With produce of such superior standard and piping hot plates, served by serveurs/serveuses holding napkins to protect their hands – in a manner that invokes the home – the aroma of each course is clear, distinct and mouth-watering. The heat encourages these natural, warming odours whilst the frequent feature of flowers, herbs and spices simply strengthen the effect.

Fourthly and finally, one samples the savours. Fashioned from the freshest and finest gifts that the season offers, flavours are clean, precise and honest, but above all, appetising. Passard is a master of texture and contrast, championing and challenging his ingredients each to accomplish what some chefs might select several to do. Where others require four, five or more different products to vary taste, consistency or add a dynamic aspect, Passard needs just a single or maybe couple of components. Alliums, for example, he uses expertly, exploiting their intrinsic layers to change each mouthful, renewing the eater’s curiosity with each new bite. He serves the first asparagus of the season with citronelle, taking advantage of the inherent sweet and bitter variance within the very vegetable, magnifying both sides of the flavour spectrum with the complimentary and conflicting tastes of caramelised garlic and lemongrass, thus amplifying what nature already provides and making a plate laden with only a couple of spears of asparagus worthy of a three-star dining room.

Additional favoured arms in the l’Arpège arsenal include vin jaune, oak-smoking, moutarde d’Orléans and aigre-doux – using elements such as honey, lime, lemon, pine nut oil, soy and balsamic vinegar separately or often together – to liven sauces, introduce some spice and stimulate the palate with their complex savours.

For the last twenty years, the chef has followed those first examples set forth by his grandmother, using his eyes and his ears, listening to the flame and slowly, gently cooking – ‘il faut aussi apprendre à maîtriser le feu afin qu’il n’agresse jamais mais plutôt qu’il caresse’. Steaming, frying in a wok and even using ovens are outlawed in his kitchen for ‘being far too aggressive…ruining colour and perfume…and drying everything out’ respectively. Here, the temperature of the pan is capped at 100ºC; poultry is cooked on the stove over the lowest possible heat in almost no liquid (except for some salted Bordier butter), turned by hand, the skin never broken, for a couple of hours; and chefs grill in salamanders set at eye level, where the heat is easier to control. These meticulous methods really do yield special results – it was during my initial time at chez Passard that I tasted the turbot and lobster that are both now the benchmarks by which all other renditions of those two ingredients are judged.

Passard promotes the relationship between chef and ingredient, which he feels has been lost through the modern use of gas and electric cookers, and urges his staff to use all their senses whilst at the stove – ‘it becomes a meditation and the kitchen, a place of listening’. As he regards cooking to be the work of the ear, he so considers it, by extension, a cousin to music. Thus, taking into account that he himself is a saxophonist and lover of jazz (in particular John Coltrane), any sort of discussion about l’Arpège is impossible without any mention of music as well as art, which together are inseparable from and underpin the restaurant’s philosophy and both of which are personified by the man, the cuisine and even by the dining room.

Passard’s own style clearly shares characteristics in common with his favourite musical form; both are creative, expressive and innovative. Whilst traditional chefs were still singing the blues, he was making it up as he went along, improvising on the off-beat – others focused on the flesh, whereas he played with forgotten vegetables. As his cooking can be symbolised by syncopation, so can his restaurant by a polyrhythm. The front-of-house and kitchen, each almost independent, marching to the beat of two bands, come together to form a harmonious whole. And the musical analogy is easily extendable with Passard playing the ‘composer’; his ingredients the ‘instruments’; flavours, textures and scents his ‘quavers, crotchets, minims and semibreves’; and so on.

From the décor further inferences may be made by the open-minded and interested eater, explicitly that the essence of l’Arpège and the very animus of the chef are encapsulated and expounded within the length and breadth of the building. Melody and the garden, Passard’s other passions, again come to the fore: a guitar grows out the pear wood; Greek figures dance and make music on the walls; the menu is laced with musical iconography; and the very name that sits above the door sings volumes. More subtly or subliminally, the space is constructed from curves, circles and rounded edges in subconscious reflection of an artist’s open and free spirit, famously opposed to strict rules and parameters, and thus, straight lines and definite edges. Then there is Passard’s affection for his crops and the countryside, which has brought the garden quietly into his home: the walls, wrapped in wavy wooden boards, imitate the trees or maybe fence that invariably borders the jardin; a mural, like those more commonly found outdoors, is painted between the two windows that look out upon the street and shows the chef carrying his produce in his hands; atop tables, replicas from the vegetable patch are set; and this green theme extends to the earthy brown hues of the room and even the chariots that have been fashioned from wood. Then again, these may just be the musings of an overactive imagination.

l’Arpège appeals and agrees with me on every level, but it is of course not perfect, or at least, not to everyone’s taste. There does appear to be a pattern that suggests those arriving later might receive meats/poultry that have been cooked longer than their liking – and this may have something to do with Passard’s own preference for the well-cooked. There is also undeniably at times a seeming chaos to the place – dishes arriving almost at random; staff entering/exiting the kitchen through a set of black doors that require a swift kick to open; such swift kicks that often lead to those same doors swinging into colleagues; a din from within suggesting anything other than concord and a careful listening to the flame and hob…

The first difficulty can be solved by simply arriving earlier, but the second is a matter of preference. Some are just naturally more at ease with a Ducassian discipline or would rather dine in a more refined, formal setting, such as one would find at l’Ambroisie. However, although disconcerting to a few, this absence of strict structure renders the experience only more interesting to others and, actually, makes the simple, careful, harmonious marriage of flavours that finally arrives all the more remarkable. It is indeed a compliment to Hélène, who conducts service sublimely and gives the impression that, without her, l’Arpège could not be l’Arpège. She is the rational, cautious force that allows Passard to express his artistic liberty and license without worry.

Whatever the individual’s exception (and it usually does revolve around a disbelief that a meal of mainly vegetables can be worth the cost on the carte) it seems that l’Arpège gets only one chance to enchant a diner. If it disappoints them on that one encounter, then the restaurant will probably never see them again. If, on the other hand, it impresses, it has gained a lifelong fan.

Each of my own experiences at l’Arpège has offered wonder, excitement and festivity. There is an atmosphere here that is hard to equal and impossible to replicate: the restaurant itself is warm and comforting; the staff welcoming; and Passard, at its centre, adds easiness, affection and whimsy to it all. Peaking through the kitchen door, greeting guests, smiling at some, giving others a tender squeeze of the shoulder as he walks past – his very presence disarms and charms those in his dining room.

Passard’s cooking is the cuisine de couleur. Light, bright and vibrant, it is born from a love of food, art, music and of life. This same spirit is embodied in all that is l’Arpège, which itself seems simply an extension of the chef’s own home and indeed of his own self. Each meal, each dish and every bite is a celebration; it is comforting, fulfilling…and it is nourishing.

84, rue de Varenne, 75007 PARIS

tel: +33 (0)1 47 05 09 06

nearest métro: Varenne

www.alain-passard.com

recent comments