Once upon a time, it was the physical geography of a land that dictated the creation of settlements. Supplies of fresh water, flat land for farming, an easily defendable position – these were the factor’s that informed the decisions of early explorers. Examples abound: in England, London(ium) lay upon a busy river-crossing; in Turkey, Byzantium controlled the access to the Black Sea as well as the route between Europe and Asia; in France, Carcassonne sat atop an impregnable hilltop…

But that was thousands of years ago. In the France of today, what with townships long-established and one’s necessary needs mostly met, just as it was nature’s hand that directed the flow and collation of essential communities, it is now the hand of man that selects the most apposite settings for his own leisure. One pertinent illustration of this is the Autoroute du Soleil. This manufactured feature, steering the modern, motorised travelling Frenchman, has neatly regulated the location of some of the country’s greatest restaurants.

For seventy years or so, droves of affluent Parisians would dribble down the Routes Nationales 6 et 7, en masse, seeking the sunny south. To fuel, feed and fatten them, restaurateurs followed, relocating old and opening new establishments along the highways. These establishments became institutions: la Côte d’Or, Lameloise, Georges Blanc, Troisgros, la Pyramide and Pic included.

Each of the above-mentioned restaurants holds or has held three Michelin stars, but one has held them longer than nearly any other, anywhere – and continuously since 1968 – Troisgros.

Jean-Baptiste Troisgros and wife Marie originally ran the small Café des Négociants in Chalon-sur-Saône, deep in Burgundy’s bosom. Together they had two sons, Jean and Pierre, born just two years apart. In 1930, just after the arrival of the youngest, the family moved to Roanne, a sleepy town west of Lyon intersected by the RN7, where they bought a modest restaurant with several rooms attached that stood opposite the train station; they named it the Hôtel-Restaurant des Platanes. Both self-taught, Jean-Baptiste managed the salle and the cellar whilst Marie prepared regional, bourgeois recipes. Although it was the wife cooking, her husband determined the cuisine. Superfluous garnishes, multi-use roux…such things were disregarded in favour of simplicity and ‘sincerity’. It was an instant success; within five years the couple had made their name and renamed themselves the Hôtel Moderne.

Following the war and occupation, the two sons, raised in the restaurant, were able to begin their training. Jean apprenticed in Paris whilst Pierre went to the Hôtel du Golf at Étretat then Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Initial training completed, the brothers reunited under Richard at Lucas Carton (where they became friends with the young Paul Bocuse) then worked under Point at La Pryamide followed by stints at Maxim’s and the Hôtel du Crillon before returning to Roanne. Taking over the kitchen, together they quickly earned their first Michelin star in 1955, sparking another name change. As les Frères Troisgros, Pierre was chef and Jean, master saucier; their father continued as maître d’hôtel and sommelier. By 1965 they had a second star; by 1968 they had their third. The accolades did not stop there though with Christian Millau announcing that at Troisgros, ‘I have discovered the best restaurant in the world,’ four years later. Such recognition attracted many fine young cooks, some of whom went on to make their own names: these included Bernard Loiseau, Marc Haeberlin and Guy Savoy. After consolidating in the seventies, the eighties saw the pair expand their business, purchasing a bordering building and launching five boutiques as well as branded products in Japan. However, in 1983, Jean died; in tribute, the Place de la Gare separating the restaurant and train station was retitled Place Jean Troisgros. During the subsequent year, Pierre’s son Michel joined him in the kitchen.

Ten years earlier, Michel had left the nearby Lycée Technique Hotelier in Grenoble – having at sixteen already met Marie-Pierre, his future wife, there – and started out on a course that would see him move across France and to Brussels, London, New York, San Francisco and Tokyo: ‘from a tiny child, I have always moved to the rhythm of a kitchen. [After Grenoble I trained] alongside Alain Chapel, Roger Vergé, Frédy Girardet, Michel Guérard, Pierre Wynants, Alice Waters, Michel Bourdin at the Connaught [was] the perfect career path and also one with a huge amount of variety.’ Although difficult, Marie-Pierre followed, working at the Hilton in Brussels, Connaught in London, Petrossian in New York and Pré des Sources in Eugénie les Bains. The couple’s next stop was supposed to be Sydney where they were prepared to open their own restaurant, but en route, they returned to Roanne. It was to be a brief, six-month stay, but Jean’s death that summer changed everything. Michel had to remain at la Maison Troisgros.

Father and son cooked together until 1993 when Pierre stepped aside and allowed Michel total control. Although he had ‘inherited taste’ from his father, to the kitchen he brought his own style: ‘my cuisine is minimalist with no flounces, sometimes playful and I always strive for balance in my respect for flavours. These flavours are precise and bright as I use acidity to effect. And I allow myself absolute freedom when it comes to seasoning.’ He also grew the family’s interests with le Central – a bistro-deli opposite the station – in the nineties; le Koumir in Moscow in 2001; la Table du Lancaster in Paris three years on; Cuisine Michel Troisgros in Tokyo in 2006; and most recently, la Colline du Colombier in the Loire countryside not far from Roanne two years after. Meanwhile, he was awarded Chef de l’Année by Gault-Millau in 2003 and with a Légion d’Honneur the year after.

Fringing the Place Jean Troisgros, which revolves around a sculpture of large, metal forks, la Maison Troisgros occupies a prominent spot. The complex is composed of multiple, inter-connected structures whose combined exterior is enveloped with lush shrubs and climbing greens. Within, the restaurant, kitchen and hotel surround a sizeable garden styled with neat trees and shaped potted plants. On one side is the massive yet serene cuisine, adjacent to the dining areas, of which there are three differently decorated ones designed by François Champsaur and seating eighty in all. The principal room, the largest and brightest, is beige and oak trim and opens onto the garden.

Large tables are distantly spread out and spread with a double layer of creamy linen; vibrant green cover plates customised by Bernaudaud and scrawled over with curvy thin scribble adorn them. A large Eric Poitevin painting hangs in the centre of the room. Outside here, above the hotel’s reception, is a small library that houses books on food and travel and boasts portraits by Dauchot and a Pia Fries relief.

During the warmer months, canapés and aperitifs are taken in the garden, where guests are also invited to read the carte.

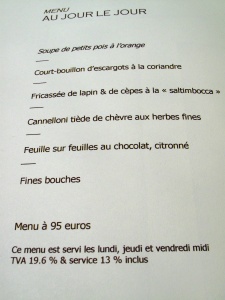

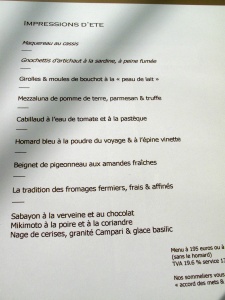

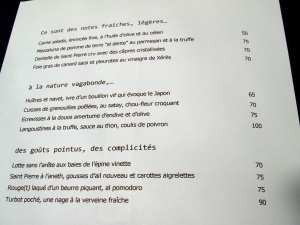

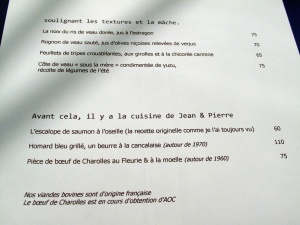

Along with the ALC – which features three classic Troisgros recipes (avant cela, il y a la cuisine de Jean & Pierre) – there is a menu du jour and extended seasonal tasting menu. Thanks to the family’s long, strong relationships with many of the region’s top winemakers, the wine list is as vast as it is impressive with over forty-thousand bottles in the cellar.

Amuse Bouche 1: Chinois de tomates au caramel; semolina avec riz soufflé, citron vert; et crackers chutney ananas, coriandre, tomate. An impeccable alabaster platter was presented carrying a colourful collection of dim sum-esque bites. Encased in herb-beer-and-sesame crust then fried in peanut oil, this ‘Chinese’ cherry tomato with its sweet, crystallised coat was spicy and crunchy on the exterior while moist and refreshing within. A small fried rectangle of creamy, smooth semolina came bound in brittle rice crispies; a wedge of lime sat besides. Lastly, a large cracker puff, topped with pineapple chutney and peeled slice of tomato, was rather hard and a little impractical, quickly breaking into many pieces.

Les Pains: Pain de mie, mais feuilleté, sésame et aux céréales. Four sorts of warm bread were served: decent baguettes of regular and sesame, seedy cereal roll and light, fluffy swells of cornbread. Alongside these sat a demi-sel butter from Charantes-Poitou.

Entrée 1: Maquereau au cassis. The shallow hollow of a wide, white plate was filled and sealed with a mirror-like layer of blackcurrant jelly; two clear-cut morsels of mackerel, glistening due to their still intact silver skins, were set upon this gelée together with a diminutive diamond of blackcurrant-vinegar-imbued onion, itself straddled by a sprig of salicorne and dotted with mustard, whilst another brace of these sat along the rim. The fruity jelly was subtly sweet and sharp whilst the mackerel, very clean. The greens added saltiness and mustard the hint of heat, but all in all, the flavours of this dish were perhaps a little too subdued.

Entrée 2: Gnochettis d’artichaut à la sardine, à peine fumée. A trio of skinny gnocchi, crowned with two tiny slivers of sardine and ribbons of orange rind, rested amidst alternating strips of artichoke heart sprinkled with sweet almond oil; the pasta, actually also made of gently smoked artichoke, were filled with béchamel. The delicate gnocchetti were nearly undifferentiable from ones of normal dough in terms of texture, though their casings were sweeter and nuttier. Inside, the velvety sauce afforded an able mouth-feel whilst the raw vegetable, with which the aromatic nut oil worked nicely, offered crunch.

Entrée 3: Girolles & moules de bouchot à la « peau de lait ». A sizeable plate with sunken middle was set forth. Across its centre, a square sheet of milk skin was stretched out, its corners stuck upon the huge brim; whilst inflated from beneath, it was simultaneously weighed down by some saffron cream. Carving open the elastic crust covering golden-brown girolle mushrooms and Bouchot mussels, more of this sunshine yellow sauce was found. Specially grown on wooden poles that project out from the sea, these moules were juicy and fleshy whilst the springy mushrooms had a peppery-fruitiness that matched the distinct saffron pleasingly. The milky surface, the consistency of which was interesting, was itself rather tasteless.

Entrée 4: Mezzaluna de pomme de terre, parmesan & truffe. A quartet of dainty half-moon shaped ravioli, scattered with pea halves and chopped mousserons, had a velouté onctueux of mushroom butter poured overtop at the table. The al dente pasta, which in a familiar twist, were in fact formed not of egg, but potato, were packed with more of the tuber, parmesan as well as truffle of Tricastin from the famous town of Richerenches (one of the largest black truffle markets in all Europe). When unwrapped, the mezzaluna imparted surprisingly strong earthy odour whilst the truffe’s savour went naturally well with the parmesan and fairy ring mushrooms. The petit pois added sweetness and some texture whilst the silky soup, enriched with jus de volaille, was comfortingly rich.

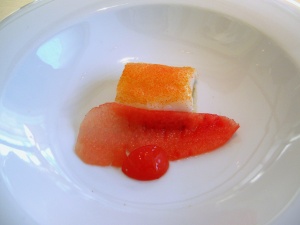

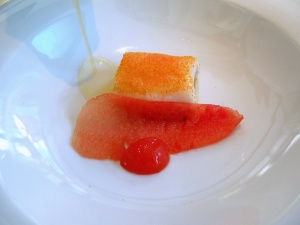

Plat Principal 1: Cabillaud à l’eau de tomate et à la pastèque. A deep bowl was brought bearing a very neat block of Breton cod encrusted with dried tomato, a wafer-like tongue of watermelon and quartered tomato that had been soaked in Jerez vinegar; tableside, the introduction of eau de tomate created a shallow, amber bath around these. This very flavourful and concentrated bouillon – similar to a fruity-sharp dashi – was warm, salty and quickly became tinged with pastèque essence. The fish, which had been poached for fifteen minutes in olive oil, remained almost raw and agreeably flaky. The tomato was faintly tart whilst the watermelon, full of succulence.

Plat Principal 2: l’Escalope de saumon à l’oseille (la recette originelle comme je l’ai toujours vu). A flat, slim peachy-pink filet of Scottish salmon sat amidst pastel yellow sauce strewn with sorrel; the plate itself was unique, depicting several of the same fish in one corner. This is one of the Troisgros family’s most celebrated creations and has remained on the restaurant’s menu since 1965; it was also one of the most widely imitated dishes of nouvelle cuisine. Based on the Loire recipe, alose à l’oseille – fresh-water shad with sorrel sauce – this was originally said to have been an improvisation by Pierre Troisgros’ mother-in-law in an attempt to finish the excess sorrel she had leftover after making sorrel soup. Here, the fried salmon, firm yet still not fully cooked through, was moist and flavoursome. The sorrel sauce of reduced white wine, Noilly Prat, mushrooms, cream, shallots and white pepper in which it swam had lovely creaminess and a distinct acidity that proved a tremendous foil for the fish.

Plat Principal 3: Homard bleu à la poudre du voyage & à l’épine vinette. Oven roasted and smeared with exotic spices, the tail of blue lobster and its claws, their skins coral-coloured and speckled with crimson barberry berries, were placed on Swiss chard stem and blades respectively. The tender lobster with its at once familiar and foreign seasoning – thyme, cinnamon, etc – was tender and toothsome. The épine vinette, a fruit more popular in South American and Persia (and believed to have been used to make the Crown of Thorns), had strong sourness that complemented the shellfish and spices, as did the barely bitter, moist chard.

Plat Principal 4: Beignet de pigeonneau aux amandes fraîches. In the dish’s centre a beignet of squab breast, wrapped in spinach and coated with squid-ink-dyed breadcrumbs and almonds, lay in jus de foie laced with Jerez vinegar; on one side came a row of griotte cherries, almond shards and small broadbeans whilst on the other, a tian of tomato and courgette flanked by the bird’s thigh. Served separately, a mousseline of aubergine was light, creamy and intense, even if eventually somewhat monotonous. The pigeon, its skin crisp and tasty, was an appealing raspberry hue and had beefy relish. The sauce held the elements together with the vegetables tending refreshment and the fruit, nuts and beans, tartness and crunch.

Les Fromages: la tradition des fromages fermiers, frais & affinés. The cheese chariot carried between thirty and forty varieties supplied by two local affineurs including one of France’s most famous, Hervé Mons. From the selection chosen, the milky Brillat Savarin, a cow’s milk from Normandy; fruity, firm tomette de brebis from the Pyrénées; dense, full Charolais, a mixed cow’s and goat’s farm cheese; and thick, creamy Tarentais from the Savoy all stood out. A sweet vanilla and tomato chutney as well as pieces of raisin bread and hazelnut butter sablés accompanied.

Dessert 1: Sabayon à la verveine et au chocolat. In a martini glass, dusted with powdered chocolate, lemon verbena sabayon concealed raspberry compote and crumbs of more choc. The airy yet thick cream had a light, lemony zing that was in harmony with the sweet acidity of the berries. Brittle bits of Valrhona, whose milky savour shared an affinity with both the other ingredients, kept the consistency interesting.

Dessert 2: Mikimoto à la poire et à la coriandre. Named after the famous Japanese jeweller, this dessert was composed of two meringue spheres split in two and reassembled to resemble an oyster shell complete with small quenelle of pear sorbet representing the pearl within. The make-believe bivalves were embedded on another thin jelly base (like the mackerel before). Well-made meringues were crisply coated whilst fluffy inside; William’s pear sorbet was more cold than anything else; and the coriander leaf left behind a nice citrus note. This jelly was rose and a little sugary.

Dessert 3: Nage de cerises, granite Campari & glace basilic. A delicate pool of cherry jus, lined with plump dicings of the same fruit, surrounded a tangy, cool granité of Campari. Atop these rested a silken scoop of excellent basil ice cream that was herbal and faintly minty-sweet. Against this, a fine meringue tile painted with ground basil powder lay askew. The strong anise edge of the alcohol struck a chord with the herb.

Petit Fours: Petit sablé pâte d’amandes; tuile de chocolat avec fruit de la passion; cigarette curry; et neige framboise et pistache. A curvy glass vase bedded with wooden potpourri bore an assortment of petit fours: pistachio and raspberry seasoned meringues; curried wafer; chocolate cracker with passion fruit; and an edible biscuit figure. The meringue bauble was pleasant and had jam hidden within. As thin as paper, the cigarette also had mild, lingering aftertaste whilst the skinny tuile held seedy, sharp crème. The multicoloured man made of marzipan was a very amusing and affectionate addition, although rather unremarkable taste-wise.

A 1998 Puligny-Montrachet Clavoillons, Domaine Leflaive and demi-bouteille of 2000 Chateauneuf du Pape, Clos des Papes, Paul Avril partnered the food.

Service was diligent and adept; the staff were relaxed and I felt fairly at ease as I ate. In many ways, it was a rather faultless performance. Yet, all the way through, I continued to discern a little distance and detachment. It was not a case of anyone being unfriendly or impolite, but there was a lack of interaction or intimacy. Others might label this professional reserve, but even were this accurate, there was still something certainly wanting here – a sense of occasion.

The menu commenced with some initial nibbles that, inspired by the Orient, were not unexpected given the chef’s predilection for the Far East, but were not memorable. The first course of maquereau au cassis, arresting and appetising in appearance, was in fact lamentably muted. This was true even more so of the gnochettis d’artichaut that came next. Things picked up with the girolles & moules and the mezzaluna, but never actually took off. Of the dishes that followed, it was the classic escalope de saumon – a supplement onto the carte – that was maybe most flavoursome. The choice and standard of cheeses were excellent, but desserts seemed merely an afterthought. When Michel was asked to describe his perfect meal, he confessed that he would ‘gladly pass on dessert’, so it ought not be a surprise desserts did not compare well to savouries here.

It was, in truth, a lacklustre lunch.

Enchanted by the legendary Troisgros name, as well as the exciting prospect of the chef’s own cuisine acidulée, the hope for a meal very memorable was high. However, although there was clearly considerable potential here, titanic expectations proved titanic-like indeed; the common, continual complaint throughout being a lack of pronounced savours and of general deliciousness.

The chef’s style was one characterised by a distinctive and creative application of classical French technique within recognisably Italian and Japanese outlines. The former influence was one that has been felt by Michel Troisgros since birth. His maternal grandmother, Anna – or as he would refer to her, la Mémé Forte – was responsible for feeding the family; thanks to her, a life-long love of tomato sauce, lemon and simplicity in cooking were established. The chef’s tastes were reinforced and broadened by a career that took him all across the world. Following on from the tradition of such kitchens as those of Chapel and Giradet, working for Guérard in New York showed him real diversity for the first time before Alice Waters presented his beloved Italian fare in a brand-new light. Living in California also re-introduced him to Asia. His father, Pierre, had spent several months as the opening chef at Maxim’s in Tokyo when Michel was still young; returning with exotic gifts and, more relevantly, exotic ingredients, his son was instantly inspired by the land of Japan. The chef has made an average of two trips there each year, for the last twenty. He is even experimenting growing wasabi near Roanne with Japanese and local farmers whilst he has also convinced a citrus seed manufacturer in the Pyrenees to grow yuzu for him.

This was all patent on the plate. The amuses, the mackerel entrée, the cabillaud and Mikimoto dessert all obviously betrayed some of this Asian motivation. Meanwhile, the gnochettis, girolles & moules and mezzaluna were evidence of the Italian influence in his cooking. However, though all these might be classified easily into such brackets, each also bore originality. This was in the form of flavour combinations – cod and watermelon; pear and coriander – and of compositions and invention with Italian recipes all reconstructed in some way – the open, milk-skin ravioli; the substitution of wheat for various, uncommon ingredients in the pasta. Additionally, on the whole, there was an acute appreciation for aesthetic; colourful, clean and attractive, some of the courses were really rather striking in their construction. It was with such technical, crafty and artistic qualities that the cuisine excelled today.

Where the meal failed to deliver was on the most important factor – taste. Subtlety can be impressive, but here savours were just too mild. In many instances, it was a case of the dish looking better than it tasted (therefore almost doubling one’s ultimate disappointment). An example would be that maquereau au cassis. Minimalist and elegant, with its elements poignantly poised upon a glass-like layer of gelée, this appeared special. Unfortunately, all the flavours were simply not marked enough for my liking or to leave a lasting impression. The same criticism can be levelled at the subsequently-served small artichoke gnocchi. Gracefully arranged around the plate, even smaller slices of sardine and snippets of orange rind delicately balanced upon each of them, this showed sophistication, but offered little else. Nevertheless, there were several exceptions to this pattern; the Tricastin truffles, l’eau de tomate and l’escalope de saumon à l’oseille, all come to mind immediately.

The escalope de saumon à l’oseille warrants singular mention. A vintage Troisgros recipe from the sixties, when the cooking borrowed much from rustic kitchen and the food had ‘earthy simplicity’, this dish sat in shocking juxtaposition to everything before and after it. How ironic it was that this symbol of nouvelle cuisine, this signature of the house of Troisgros commemorated by the railway station opposite the restaurant that was once repainted salmon and green in its tribute (although it has recently been refurbished), was now but an arresting anachronism in the context of this meal. Yet, on the other hand, as if just to complicate the matter a little more, even though far less prim and essential in its presentation and a little less polished, this actually bore the strongest flavours. Whereas the rest of this menu was typified by gentle, mild savours whose revelation and pleasure required more of my effort and determination, here the richness of the salmon, the cutting acidity of the sorrel, abounded unabashedly in every bite. This last detail leads me to my last major point.

Acidity. ‘…[it] is a recurring theme in my cooking. It’s almost everywhere and often helps structure a dish, creating a backbone – the elements in the plate all relate to it and it makes sense of the whole. If bitterness represents a serious side in the palate of taste, acidity often provides a note of irony.’ It is fair to say that the chef has built a reputation on his penchant for aigre-doux and acidité (something else he owes to la Mémé Forte and her use of lemons and citrus). Thus I thought it rather curious that the course in which the most sharpness appeared was one not conceived by Michel himself, but by his grandfather. Taken alone, this was surely not an issue, but because it was almost totally missing from the rest of the meal, this was a concern.

What with each plate neither ever really fulfilling the potential of the restaurant or the promise it itself professed to possess upon its very arrival, nearly every dish was tainted with some degree of disappointment: therefore, it was only inevitable that the entire experience would fall fairly short of success. Furthermore, any frustrations were not ones attributable to the incidence of errors or to any single thing explicitly disagreeable, but to a common mundaneness. The food was forgettable and the acclaimed, the sought-after acidulée absent from the cuisine.

This flatness in the cooking seemed echoed by the earlier-described dullness in service; just as the dishes lacked life, the staff did too. That sensation that one is eating somewhere truly special – that ought to be a central aspect of dining at this level – was definitely not there.

If truth be told, I felt as if I could have been having this meal at any table in any town almost anywhere…and that is certainly not what I considered ‘worth the trip for’.

Place Jean Troisgros, 42 300 Roanne, France

tel: +33 (0)4 77 71 66 97

A lovely report….only halfway through….but I have a comment to your statement that they have the 3 star rating longer than anyone else….to my knowledge Auberge de I´ll has their 3 star rating since 1967. Although I fail to understand why….but thats another story.

I cannot comment on the Haeberlin’s as I have not eaten there.

However Paul Bocuse has had three Michelin stars longer than anyone else – since 1965, if I recall rightly.

Bo, Food Snob:

Regarding your reference to the longest holder of a 3* Michelin star, I believe this goes to Chef Fernand Point.

FS,

I’m glad you added the salmon to the tasting menu. It is too bad it is not regularly on it. I first had it in 1967. You rightly say that it was an enormous influence on all of French cooking. There were two elements of innovation:

1. The achievment of flavorful acidity through the lavish use of a fresh ingredient which was not highly regarded at the time.

2. It was the first famous dish which used one-side cooking in a non-stick pan, which had just been invented then. Of course, this required top quality salmon.

Bests,

Michael

Dear Food Snob,

A very interesting review, although I have to admit I am disappointed to hear that the flavors didn’t live up to the quite strikingly beautiful presentation of many of the dishes. This was always a place I had considered making a special trip to go to, but given what you say, it seems it is probably not worth the effort and that such a trip would be better directed elsewhere.

I totally understand what you are getting at in regards to the service. At too many Michelin-starred establishments I have found that the service, while technically quite impeccable, lacks that certain level of engagement and personal attention which one hopes (and expects) to receive at such restaurants, indeed (as you say) making it seem all the more like a truly special occasion.

As usual, wonderful photos, just a shame that the visuals created even more disappoint as a result of their beauty.

PS – I also enjoyed the potted history of the Troisgros family, a very interesting and worthwhile read.

Best regards,

LF

It seems a long time since your last post. Glad to see you’re back!

I think you summed up my sentiments as well … mild flavors are no excuse for no taste. Too mild. Also the location sort of pushed the experience over the edge for me … all so awkward and strange.

Dear all,

The feeling to be on a very special evening out, to eat exceptionally well and to enjoy service that is not only technically perfect but also warm and personal is the exact reason why l’auberge the l’ill has had three stars for ages. It’s classical yes, but still has its place next to the ones that get more attention nowadays. I’ve been dissapointed and thrilled in San Sebastian but if I really don’t wanna take any risk and still eat where it’s worth the trip, Haeberlin is the place to be.

That is the most strange review …

I still have all these explosive flavors in my mouth, as well as the textures .

Dear Foodsnob, maybe you aren’t ready for this 😉

Although I totally agree on the service .

@Michael Thanks for the extra details!

@LF Cheers. I mean there are plenty of places nearby – or elsewhere – worth a special trip. And bear in mind, this was just my experience. Others have enjoyed it more (like Cookie ^^).

@Foodmiles Well, my last post before this one was December…not as long as the June date suggests (the write up is dated back to the day of the meal).

@Adam I assume you mean the decor/interior rather than the actual physical location (ie. in Roanne, lol). But agreed.

@Joris Thank you for your input.

@chère Cookie ‘strange’? merci. that’s exactly what I was aiming for! 😛

Maybe too many great experiences too quickly, non? I have an annoying friend who is always telling me, ‘slow down, take it easy’. (entre nous, je pense qu’elle est une folle…).

sorry FB… i hate to tell you this but i had worked with troisgros’ kitchen staffs on a professional level before and at least one of his chefs has serious finger-licking problem. i would NEVER, EVER go to the restaurant or recommend anyone to go.

Only 5,500 words this time…

God, what a blog! I have just discovered it, and I am going to read now…

I enjoy browsing your blog, I usually learn something new facts.

Emily R.

@Random Nomad …interesting. haha.

@Douglas Excuse me?! Have you not noticed my new style? The last few (maybe two) posts have been only 4,000 words or less!! 😛

@Magdalena Thank you.

I am, I`m afraid,the very essence of naivety asking this question but it`s worth a try. Is the recipe for saumon al`oseille, as enjoyed by me at la Maison Trois Gros in 1989 en route to watch England v. Argentina in the World Cup, available anywhere. Thanks Roger Court

I wondered if you had been to Le Grand Couvert, the much simpler restaurant that Michel Troisgros must have opened around the time you went to the Maison Troisgros? The Art of Eating carried an intriguing article about it last year, but the writer was clearly a friend of Troisgros’s. We’re thinking of staying and eating there but I’m hesitant given your very negative review of his more upscale establishment. And, on that note, we wondered if you had any suggestions of restaurant-inns in France or Italy where you can eat wonderfully and stay the night?(As part of our honeymoon, during which we were thinking of a stint in Paris also, and l’Arpege for dinner. I don’t know if you have any thoughts on dinner there? We have only eaten lunch previously.)