There was a hard, dark side to my family,’ begins the chef whose face is now synonymous with a smile. ‘[My father] was an introverted man, not at all expressive. He was orphaned and had been brought up by a strict and authoritative grandmother.’ Jean-Claude Gagnaire, an Apinac native, ran a one-starred restaurant in Saint-Étienne. ‘The motto in my family was do your duty…I was the eldest in the family of four and I knew what I had to do.’

Thus Pierre Gagnaire feels he ‘never had any choice, I just had to be a chef. I put my foot inside the system – and couldn’t get out of it,’ and so, although he had enjoyed his time at school, where he ‘discovered the pleasure of books’, by fourteen he was already an apprentice in the pâtisserie of Jean Vignard’s Chez Juliette, one of Lyon’s leading restaurants. A couple years subsequently, he was at another of the city’s institutions, Tante Alice, prior to a summer internship in 1968 at Paul Bocuse – ‘I was frightened by him. I was too impressed by him to ever work for him.’ He then spent a year at the casino de Charbonnières-les-Bains and learned the art of rotisserie after which, just as another prominent Parisian chef, Pascal Barbot, would do similarly years on, Gagnaire completed his military service as a cuisiner-amiral on board le Surcouf; ‘I loved it,’ he recalls. In 1973, he returned to France and Paris, working at the Intercontinental before the legendary Lucas Carton, but he was abroad again two years later as he set off on a petit tour du monde, focusing on the New World.

It was not until 1976 that the chef eventually returned to and took charge of the familial restaurant, le Clos Fleury, in industrial Saint-Étienne. ‘It was like being given a car with no papers. By this time I had realised that cooking was how I could express myself, but with my father in the background. I could not do what I wanted.’ In spite of retaining his inherited star, he describes the four years he was there as ‘a bad experience…a mess’. It was a testing time indeed – customers were even unhappy that their French chef had married a German. It was only in 1980, when Jean-Claude retired, that he was able to close le Clos Fleury and open his own venture, Aux Passementiers. In only his first year he had won his first star and, in 1986, his second. By 1993 he at last had all three.

Nevertheless, even this supreme reward was not enough to save the restaurant from the ultimate embarrassment, bankruptcy, three years later. ‘I lost absolutely everything in one day, all I’d worked for and built. But I would have lost my soul if I’d stayed there and adapted to the taste of the bourgeoisie.’ He needed a clean start. Therefore, six months on, he moved to Paris and took over the Italian, Bice, in the Hôtel Balzac. He retained two of his stars. ’It was a rebirth,’ and it took the chef just another two years to redeem his third star.

The turn of the century brought with it further reward. In 2001, Gagnaire began working closely with ‘the father of molecular gastronomy’, Hervé This, a professor at the Collège de France – an affiliation still strong today. A string of restaurant launches has ensued since: Sketch, London (2002); Gaya Rive Gauche, Paris (2004); Pierre Gagnaire, Tokyo (2005); Pierre, Hong Kong (2006); Hôtel « Les Airelles », Courchevel (2007); Pierre Gagnaire, Seoul (2008); Reflets par Pierre Gagnaire, Dubai (2008); Twist, Las Vegas (2009); les Menus par Pierre Gagnaire, Moscow (2010); and most recently, the reopening of a Pierre Gagnaire in Tokyo after the closer of the former in 2009 (2010).

But rue Balzac remains ‘mon cœur’. A few moments uphill walk from the Champs-Elysées stands the nineteenth-century luxury hotel at the crossroads of two roads named for famous writers: rue Balzac and rue Lord Byron. Bright but basic red plaques spelling out the chef’s name and the iconic π symbol are the only suggestions that the restaurant resides within the same building. Once inside, Pierre Gagnaire’s entrance is on the right of the glamorous, gilded lobby.

A dim, drawn-out corridor leads past the bar and onto a double-decked dining room most recently renovated in 2004 by Michèle Halard. Several, sizeable circular tables cover the lower level whilst half-a-dozen smaller ones line the two raised levels either side of the main space. The ceiling is sombre grey; walls light, lacquered wood; and carpet, a narrow-pinstripe of greens and browns. Large, latticed windows look out upon the street outside yet, concealed without with ivy, maintain the interior’s privacy. Pieces of abstract art, some on loan from Galerie Lelong and flower arrangements by Christian Tortu are scattered around the room and a glass-faced wine cellar fringes the furthest wall. Belle Époque details abound in the cerulean-coloured insets stencilled in ebony floral patterns, suspended chandelier, black-capped table lamps and soft jazz playing in the background. Well-spaced tables are laid with white piqué linens, contemporary crockery from Feelings (Bernaudaud, Raynaud and JL Coquet arrive later), little π pebble and a silver vase with short yellow canna lily.

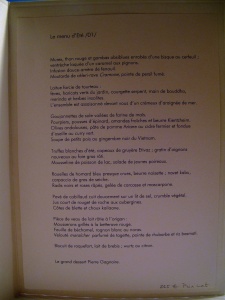

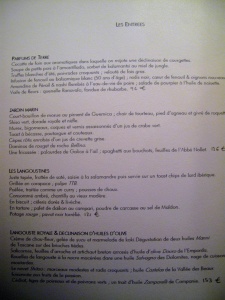

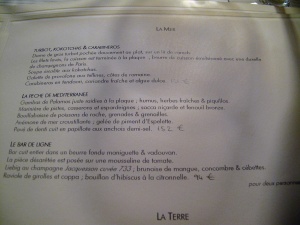

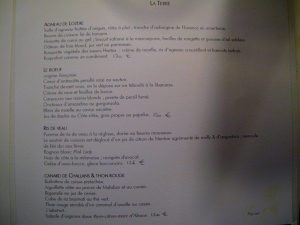

The carte is not a curt affair. Along with a menu du marché and lengthy, seasonal tasting menu that evolves over the period, there is an extended ALC listing short, succinct subheadings (parfums de terre; jardin marin; turbot, kokotchas & carabineros…) followed by several lines of occasionally purple detail.

It was as I perused these scripts that Gagnaire entered the dining room to greet his guests. When he came to my table, unexpectedly he recognised me from my last meal at Sketch. After a short conversation, the chef kindly volunteered to cook for me himself – needless to say, I indulged him…

Amuse Bouche 1: Collection de la croquette et sablés; pâte à filo curcuma et huile d’olive de Toscane avec thym frais, côte de romaine, crème d’anchois; un plat de cercles rouges. The first set of amuses totalled a trio of separate servings.

A tray of canapés carried three spherical nibbles: a petite croquette de béchamel, sablé au fromage and a sablé aux amandes. The croquette, warm, crumbly, creamy and mild, was the start of a series of increasing nuttiness and textural solidity which – via the crackly, nutty-sweet vieux comté biscuit – ended with the hard, almond cracker.

Next, a small bowl bore a raised shot glass that held a pâte à filo curcuma chip and sprig of fresh thyme sitting together in shallow Tuscan huile d’olive. The curried stick and thyme went well with the peppery, herby Italian oil whilst a cut of romaine rib glazed with anchovy, balanced on the brim beneath, was cooling and salty.

Subsequent to these came a circular study in reds. Atop a wide white plate, rippled with easy etchings, sat a threesome of varyingly round items. The largest – a dipped dish containing rust-coloured chestnut tuile, topped with pointe de thon rouge, that concealed a grainy carrot velouté – rested slightly off-centre. On the far left lip, a tall, oversized thimble filled with syrupy fruit ratatouille was capped with a thin beetroot crisp and crowned with a tiny brick of its jelly. Finally, almost opposite, lay a little ladle cradling a spiralled gelée of lemon balm over a disc of watermelon reposing in its juice.

Les Pains: Baguette, pain brioché et tuile croustillante aux olives noires. Miniature brioche loaf was faintly crusty and hardly heavy; sharply-pointed baguette had more crunch and tore nicely; and brittle black olive crisp had good flavour. Two butters – both Bordier – were brought out on their own tableware: a silver coaster of unrefined beurre demi-sel; and a green saucer with a brick of beurre aux algues.

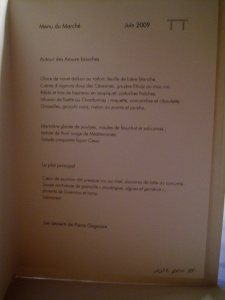

Amuse Bouche 2: Glace de navet daïkon au raifort, feuille de bière blanche; crème d’oignons doux des Cévennes, gruyère Etivaz au mac-vin; râble et foie de lapereau en saupiquet, pistaches fraîches; groseilles, gnocchi noirs, melon au poivre et pursha; et infusion de lisette au chardonnay – roquette, comcombre et ciboulette. The second array of amuses arrived in five parts.

A squared central dish was found in the customary spot as four smaller, differently-shaped ones were dealt out in a semicircle around it. One began with horseradish mousse mounted with a jellied layer of white beer and quenelle of daikon ice cream spiked through with balsamic vinegar and finished with a wafer of raw radish. The raifort’s spiciness played well against the sweetness of the bière – a theme mirrored by the balsamic that agreeably pierced the smooth, tasty glace. A cup of Cevennes onion compote scattered with Macvin-soaked Etivaz Gruyère succeeded this. Here the creamy, potent cheese failed to alleviate the savoury-sweet crème d’oignons, fortified with jus de boeuf, which was just too strong for my liking.

A self-standing spoon offered a bite of the Burgundian classic, baby rabbit in a creamy wine and vinegar sauce. The pretty pink and green stack of shredded saddle and liver mixed with grated fresh pistachio and garnished with reine des prés was, together, tender, mellow and mildly sweet. A colourful mélange of melon and squid ink gnocchi dressed with Persian lime and peppered red currant sauce was sweet, sour and salty at once.

Lastly, lifting the lid of a small ceramic crock revealed a rosy-fleshed, glaucous-skinned morsel of baby mackerel swimming in its dark chardonnay-infused bouillon; this very clean fish was of clear quality.

Entrée 1: le Rouget. A large silver tray with two bowls was delivered tableside. The smaller of these was shown off before its contents – filet of pan-fried red mullet broken apart into its individual filaments and mingled with peeled almonds, parsley and golden prunes from Iran – were spooned into the larger, whose base was already lined with thick tomato bisque.

Scarlet red tomato jus formed a rich, reflective surface around the collection of pink, alabaster and yellow that had been assembled in the plate’s centre. This gazpacho-esque sauce was full of bright, almost tangy savour whilst the denser paste beneath had an agreeably coarse consistency. The tasty mullet had innate accord with the tomato as well as the nuts that tendered their subtly sweet crunch. The inclusion of the Iranian prunes was inspired; gently warmed, they were faintly firm while simultaneously strongly sharp and sweet, thus complimenting and contrasting the flavours already afforded by the other elements.

Entrée 2: Agneau de Lozère & Saint Jacques. Removing the cloche revealed a cluster of roughly-chopped salicorne and mange tout that together resembled the grassy sheet over a small knoll. This verdancy was interrupted by the matted ivory shimmer from a sprinkling of diced scallops and the sneaking appearance of pasta underneath.

Sweeping away the greens unveiled a single, sizeable cannelloni of lamb confit mizzled with its own jus and chives. The pasta was just substantial enough for its presence to be felt whilst the sauce, concentrated and intense. Crisp and salty-sweet vegetables alongside the caramelised scallops were a lovely foil to the rich, meaty filling of shredded lamb from Lozère.

Plat Principal 1: Le Boeuf: Origine Française; cube de riz Basmati au thé vert; thon rouge enrobé d’un caramel d’oseille au cassis; l’abstrait… This course encompassed a principal plate and three smaller ones.

At first concealed below a loosely-laid silver cover, slices of braised beef, resting in a ring, had been drizzled with deep maroon cherry jus and arranged with lightly steamed leaves of lettuce overtop. The tender pieces of peppered French meat from boucherie Nivernaise were animated by the tart-sweetness of the full, robust fruit sauce as the succulent greens provided relief as required.

Additional dishes included, in turn, two squares of fatty mi-cuit red tuna coated in sorrel syrup, rounded off with sorrel leaf and very good duck skin crisps and accompanied by caramelised blackcurrant; a lettuce-raviole of warm, velvety basmati rice, cooked al dente, and glazed in a light olive oil-matcha cream; and small cuts of more beef and slithers of onion topped with a pinkish cube introduced as ‘l’abstrait’. This last item’s ingredients were difficult to identify – creamy in texture and barely bread-like in taste, it was also somewhat sweet and smoky whilst possessing umami. Soon it was evident though that this was actually the chef’s intelligent jesting: even if its makeup may have been initially uncertain, in savour and semblance it was unmistakeably familiar – it was meant to be bone marrow.

…As it happens, this mock marrow was composed from a mixture of smoked mousse, beef consommé, bread and kanten.

The savouries over with, Le Grand Dessert de Pierre Gagnaire started. Although titled in the singular, this comprised a succession of ‘desserts inspirés de la pâtisserie traditionnelle Française; elaborés à partir de fruits, de légumes de saison, de confiseries peu sucrées, de chocolats…’ some arriving alone, others together.

Dessert 1: Salades de fruits. Melon pieces in fruit syrup were placed under a crunchy, fennel tuile upon which a slice of mango, made to look like an egg yolk, came covered with yellow passion fruit seeds and pulp. The bitter liquid below balanced out the mildly acidic-sweet maracuyá.

Dessert 2: Pain perdu. Peach ice cream sat surrounded by poppy jelly containing diced peach chunks and a small square of French toast was seated on the plate’s rim, garnished with a leaf of lemon verbena. With its unique, perfumed sweetness, the ice cream was very pleasing, however the poppy rather faint and soft pain perdu, whilst well-made, did not seem to sit naturally with the rest.

Dessert 3: Fraises à la crème. A solitary strawberry, its end tipped in slightly viscous cream, was set in the centre of a saucer of rose sugar. This course’s constituents all shared an easy affinity with each other, but ultimately this was a portion more memorable for being pretty than it was for being tasty.

Dessert 4: Granité à la framboise et cerise. Another serving in the most romantic shades of red and pink entailed juicy raspberry and cherry granita over lemon crème; blanched almond halves were propped atop while a brace of lemon balm blades were affixed to the bowl’s side. Even though some sloppy plating meant that the glue attaching these leaves was still visible this Sicilian reinvention was, nevertheless, simply delightful.

Dessert 5: Gateau au chocolat. Over red fruit coulis stood a jenga-like tower of pâte sablée, pistachio mousse, hazelnut biscuit and at last génoise au chocolat – all in equal squares, but of unequal depths and different colours; liquid chocolate truffles, one light and another dark, lay either side of the confectionary column, which was drizzled with warm, runny chocolate sauce at the table. This near-deconstruction of a cake was just decent with each slice proffering varying textures and distinct tastes. The two explosive truffles were highlights.

Dessert 6: Verrine cassis. A martini glass brought blackcurrant in three ways: at its base could be found sweet, cold compote, above which a crisp blackcurrant wafer held separate a frothy top of fruity-tart foam dressed with a pansy flower. This was a refreshing, clean finish to the desserts.

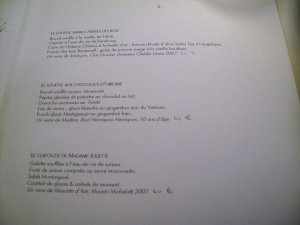

Petit Fours: Roulé au chocolat blanc avec citron; ‘cerise’ de pâte d’amande; pâte de pistache; ficelles à la rhubarbe; cigarette au chocolat menthe; roulé au chocolat noir avec kirsch; et bâton de chocolat ivre. A long ceramic semi-cylinder that appeared with the first of the sweet courses carried several dainties. There was a sharp white chocolate roll filled with lemon curd; marzipan shaped like a cherry, but really encasing spicy blackcurrant; strong, firm pistachio paste; delectable, sharp threads of rhubarb; bitter choc stick flavoured with mint; dark chocolate with kirsh; and a sticky, fruity cocoa tube imbued with alcohol.

Mignardises: Truffes de la maison. Coffee was complimented by three types of chocolate: a milky Tonka bean palet d’or and monogrammed dark and light truffles.

It is a little difficult to comment on service. On the whole, the staff were friendly, able and efficient. The maître d’hôtel, Hervé Parmentier, seemed diligent, attentive and amusing – replete with a moustache well-suited to a British sergeant major, he appeared almost as eccentric as his chef and twice as frenetic. However, I did have a gripe, but it related to something specifically concerning my meal and an issue that would, under normal circumstances, most likely not have arisen. At least, I shall assume so.

What troubled me a little was that my serveuse was almost utterly unable to explain any of the dishes. Typically such a trifling dilemma might be disregarded, but I found it especially demanding happening here – at Pierre Gagnaire. This is because this chef, more than most, has a penchant for quite quixotic ingredients, particularly herbs and spices, which might make a huge difference to a dish. Without the serveuse’s aid, it required more effort on my part to attempt to discover and distinguish these, thus diminishing my ease. Furthermore, her inability to assist fully seemed to also make her more uncomfortable and maybe nervous, which did not benefit either one of us.

Fortunately, this flaw in service did not frustrate my enjoyment of the food.

Of the entire two sets of amuses, little stands out as memorable. The ratatouille, glace de navet daïkon au raifort and râble et foie de lapereau en saupiquet were the only notably nicer moments whilst the crème d’oignons doux des Cévennes the only one to which I took a dislike. Additionally, although the butter was very good, the bread was unremarkable. Finally, desserts followed in the same vein as amuses: many were simply forgettable with just the granité de pêche et cerise and verrine cassis more than fine.

Nonetheless, although it may sound as if riddled with shortcomings and so less than successful, this lunch was nothing of the sort. First, these aforementioned ‘unremarkable’ and ‘forgettable’ courses were still decent, even if less than exceptional – and certainly not unpleasant (except for crème d’oignons doux des Cévennes that is). Secondly, the dishes proper – specifically le rouget and agneau de Lozère & Saint Jacques – were simply stunning; but before focusing on these in more detail, I will comment further on what came prior to them.

Even if the amuses were not delicious to my mind, there were still entertaining. Given that these plates were prepared ahead and with more time (unlike the improvised entrées and main), they painted a better picture of Gagnaire’s intellectual approach and the deep thought that he applies to structure in his cuisine. For instance, regarding the very first snacks offered, there was their already-explained order and rationale. This principle extended to that whole course: those nibbles had the heaviest of flavours and densest of textures; the pâte à filo curcuma et huile d’olive de Toscane that followed was lighter in both respects; whilst one finished with soft and fruity items. Additionally, this last collection of bites showed the same sort of keen consideration. Each element matched sweet and savoury as well as smoothness and crunch – and again, the final watermelon-verveine morsel was the lightest and most refreshing, almost cleansing the palate.

The second series of snacks was just as deliberate. At a glance, one could immediately discern that every dish was of a special shape whilst the content of each was also of another colour. The distinction did not end there as all the plates presented a different foodstuff – vegetable, dairy, meat, fruit and fish. Lastly, each element’s temperature was taken into account: one commenced with the coldest (the ice cream) and ended with the warmest (bouillon).

With the rouget, the chef’s intentions were more open to contemplation. He was obviously teaming together tastes typical to the Mediterranean – red mullet, tomato, almond, dried plum – but, as far as I am aware, in an unfamiliar permutation. The recipe resembled something Italian, Spanish, North African and maybe more all at once. Could he have been attempting a play on paella, wherein the almonds represent grains of rice? Or was this Gagnaire’s reinterpretation of a gazpacho or even a bouillabaisse? The motivation might be unclear, but the result was certainly something excellent.

The agneau de Lozère & Saint Jacques was another lesson in flavour pairing. Whilst many may be surprised to see lamb and scallops reside side by side, Gagnaire made them seem the most natural of couples and, aided by the sweet and salty greens, the two remained in refreshing and tasty balance. After all, he has been quoted saying, ‘God put all those ingredients on Earth…why not use them all?’ Furthermore, whilst many may be nearly offended to observe these Saint Jacques cut into small pieces and not kept whole, such concerns fail to even register with him. Thus did this plate illustrate an important detail of the chef’s cuisine: there are no rules.

Random combinations of produce, unusual treatments of products, the introduction of science into cooking…Gagnaire utilises all such practices without prejudice. Actually, the only limits he appears to allow himself to accept are those surrounding the quality of his ingredients and a desire to pursue a more organic direction in molecular gastronomy. To help him realise the latter, he teamed up with bio-chemist Hervé This. Their collaboration has become famous and its fruits can be tasted through the würtzs, liebigs, abstances and, as was the case today, abstraits, that litter the menus of his restaurants.

Indeed, even though Pierre Gagnaire is considered one of the most progressive and modern of chefs, there remains a distinctly classic stroke to his style. Regularly deemed as baroque, there are aspects of his meals that resemble those from the eighteenth century. This is most identifiable in the delivery of his dishes. Two to three hundred years ago, it was the custom of the French royal court to serve à la française – all at the same time – and hence create drama and excitement. At the same time, there was also a flourish in the crafts industries with new serving vessels created to add to this spectacle. Gagnaire exercises such tactics himself. From the very onset, the diner is subject to a flurry of small treats that arrive altogether or slightly staggered – each served in crockery unique to it. The effect of this is three-fold. There is the same visual thrill; a generous notion of the kitchen engendered; whilst one is also left a little intoxicated – maybe even intentionally overwhelmed – by the multitude of assorted savours and aromas.

Naturally, Gagnaire being Gagnaire, nothing stays as it is. Courses will drift between service à la française and à la russe – individual dishes – at the chef’s command although amuses and the plat principal do tend to be multi-plate events whilst desserts are delivered usually singly yet in quick succession.

Such is the nature of the cuisine. Surprise, shock, intrigue…are essential elements of dining here. The chef himself likens cooking to jazz with its inherent improvisation whilst regarding it as also ‘more like an intellectual game’. In his own words, his is a ‘lively approach which takes risks and, as my critics say, occasionally goes overboard. I trust that these people will forgive my over-enthusiasm!’

‘His cuisine is hard to classify because it is guided by inspiration. It’s modern, it’s baroque, it’s self-taught. You get the feeling he’s there with his ingredients enjoying himself and if you chose the same dish on two consecutive days, it would be slightly different’, explains Troisgros, trying to articulate the essence of eating here. ‘My style,’ says Gagnaire himself, ‘is joyous, immediate and tries to tell a story. I want to make people dream and bring them somewhere they don’t know’.

These notes seem almost incomplete without some mention about how others regard Gagnaire or at least visits to his establishments. He is undeniably someone who seems to divide opinion: diners love his food or hate it; his meals are incredible or terrible. Considering that he is somewhat of an agitator, someone who seeks a reaction from his guests, the fact that attitudes about him lie around the extremes is hardly startling. From my own appraisal – which comprises two occasions at Sketch, London and this one at rue Balzac wherein, admittedly, I was fortunate enough to have him cook impromptu for me himself – I must confess that I have been very impressed. Effective, colourful and intimate, his is a cuisine that I find especially attractive and deeply personal. However, this being said and really for this very reason, I feel that I would not eat at any of his restaurants were he not in the kitchen that day. His cooking is so ingrained in his personality and mentality that was he not at the stove, I cannot believe that my assessment would be the same as if he were…

Genius is not a label I bandy about very willingly – there is indeed one chef, although increasingly I am recognising it in another, whose talents I sincerely ascribe that term to. However, Gagnaire is an exceptional character. ‘Wizard’, maniac, mastermind, alchemist, the ‘Matisse of cooking’, are just some of the titles bestowed upon him. In all fairness, each is probably as accurate as any of the others…and to my mind, he is as much a chef as he is an intellectual; as much an artist as he is scientist; as mad as he is brilliant.

A strict classical training has given him the tools and techniques whilst a childlike curiosity has equipped him with almost an unrivalled repertoire of ingredients. Led by his artistic impulses and liberal enthusiasm, informed by his friendship with This and directed by a methodical and meticulous manner, Gagnaire expresses himself unreservedly with great precision and poignancy whilst delivering an experience for the senses, full of gourmandise, and always anything but pedestrian.

‘My goal is to infuse my cooking with feeling and intelligence. People need poetry, tenderness and well-made things…and being ‘good’ means opening up the range of emotions.’

6, rue Balzac, Paris 75008

tel: +33 01 58 36 12 50

nearest metro: George V

www.pierre-gagnaire.com

I enjoyed your review very much it has the usual detail and insight into both the Chef and the cuisine.

I first tasted Pierre Gagnaire’s food in Saint Étienne in the 90’s after a tip off he already had ** and then caught up with him again in rue Balzac in 1999 and have eaten there many times since. I believe the restaurant in Saint Étienne went bust which is not a total surprise as if my memory serves me right generosity, top quality produce and very reasonable pricing were the order of the day.

Every single meal has been remarkable in terms of innovation, procurement/combination of top notch ingredients and service levels.

Sketch on the other hand after 3 attempts has proved to be the exact opposite in every respect.

Have not tried any of the other “difussion” establishments in Japan, Hong Kong or the US.

alchemist is apt – i need to go back

@Gastro1 Cheers. That’s right, it went bankrupt in 2006. Very cool you were able to experience that though.

I was fortunate at Sketch. He was in the kitchen and you could almost sense his touch on the plates. I won’t forget it.

@Chuck I love your Gagnaire posts………

FS,

I have the impression that when he was cooking for you impromptu, the dishes were significantly less complicated than if you had had the tasting menu. They might have been better for it, but you have less of the Gagnaire experience.

Another wonderful article FS!

Also, rather timely: I am currently ruminating on the idea of making a drive over to Las Vegas for his recently opened “Twist.” While I’d much rather sample his Parisian flagship as a first experience, I must say the idea of speedy 4 hour drive instead of the cross-country/transatlantic flight has substantial merit. I am fascinated by Pierre Gagnaire and his whimsical/molecular-gastronomic take, mostly because I have yet to fall in love with a chef with those tendencies. I recently tried Andres’ Bazaar in Los Angeles and was substantially disappointed (conversely I agree, Passard is a genius!). Some of my friends rave about Gagnaire and yet he still remains elusive to me. I’ve only had the opportunity to dine at his more casual establishment in Paris: “Gaya Par Pierre Gagnaire,” which was underwhelming on many levels. But still… he remains fascinating to me.

Basically I’m tryin to figure our whether it is even worth it to try “Twist” and really experience Pierre’s food (which it seems would depend if he were there?), when my very limited budget would perhaps be much better spent on another perennial trip to Urasawa! One can see the dilemma…

Again. Great post. Thank you so much for your work.

What can I say?

Du grand art!

Both Gagnaire and your post. I will try to go there in and of May.

unreadable

Hello! I really have enjoyed all of your Paris posts immensely – thanks so much for sharing your experiences! They look amazing!

I’m going to Paris next week and am grappling with the decision of whether to have lunch at Ledoyen or Pierre Gagnaire. Do you have any advice? I adore good food and though ambiance is important, the food is #1 for me in my priorities. Many have warned about the inconsistency of Gagnaire.

Also, I am trying to decide between La Regalade St. Honore and Chez L’Ami Jean. Any advice on those? I think I may stop into Chez Josephine for a really old school “french food” experience. I’m guessing that both CLA and LRSH would offer something all at once very “french” but also exciting and wonderful?

Thank you for all your help!

Gagnaire was a truly humongous disappointment wonderfully hyped by a gaggle of geese in Paris with the message being carried far and near by pigeons from all the world. the baguettes by the way as i remember were even second rate . the waiters were preening and in one’s face oddly enough the best thing was the wine served and selected by a decorous chap who knew his vines. this is the first time i have been on your site and i much look forward to peeking around it. i would say that the french do not do new cuisine that well, but are marvels always at centuries past.