While Ulaanbaatar may not be a well-known destination city, it has plenty of interest to offer visitors, especially if they are interested in Buddhism, history, nature or art. Here’s my list of the places I’ve found so rewarding that I’ve been back to most of them twice so far and will probably visit them again.

1. Gandantegchinlen Khiid– the full name translates as “the great place of complete joy”. More commonly known as Gandan Monastery, it was built starting in 1838. Ninety-nine years later, it was one of the very few monasteries to survive the Stalin-style purges that led to the destruction of hundreds of temples and the deaths of an estimated 17,000 monks. These days, with the revival of Buddhism in Mongolia, Gandan is a busy place. There are a number of temples. Visitors are only allowed into the main one, as seen below, Migjjid Janraisig Sum. Within it is an enormous statue of Buddha, well worth the modest price of admission.

2. Chojin Lama Temple Museum– Smaller than Gandan, but with an intimate, decorative charm, this old temple is tucked away down a side street and is surrounded on three sides by modern buildings. But once inside the walls, it’s a place of beauty and peace. Construction started in 1904 and took four years. It was saved from destruction for use as an example of past “feudal” ways. Although it is considered a museum and there don’t seem to be any monks in attendance, every time I’ve been there, people have been in the temples praying and leaving offerings. There is also a concrete ger “Art Shop” shop on the grounds that can be accessed without paying admission. I think it’s the best place in UB for souvenirs, although it doesn’t have the wide selection you can find at the State Department Store. What it does have is the feeling of a treasure hunt in a curiosity shop.

3. The Natural History Museum– Speaking of curiosity shops, the Natural History Museum is like a survivor from another time. It needs and deserves to be modernized, but something charming and fun will be lost when that happens. It is home to a very good collection of dinosaur fossils that have been found in Mongolia over the years, including eggs and a huge Tarbosaurus. The most spectacular fossil on display is the famous “fighting dinosaurs”, a protoceratops and a velociraptor locked in mortal combat as they were possibly trapped in a mud slide. Another personal favorite, which I hope will be preserved in any modernization, is the “camel room”, see below.

4. The National Museum of Mongolian History– Only a block away from the Natural History Museum, the history museum has been renovated to an international standard. There are three floors of exhibits, starting with the superb section of stone and bronze age items on the first floor, an amazing display of ethnic Mongol historic costume and jewelry on the second floor, the can’t-be-missed third floor collection of artifacts from the time of the Mongol Empire and on through to the changeover twenty years ago from socialism to democracy.

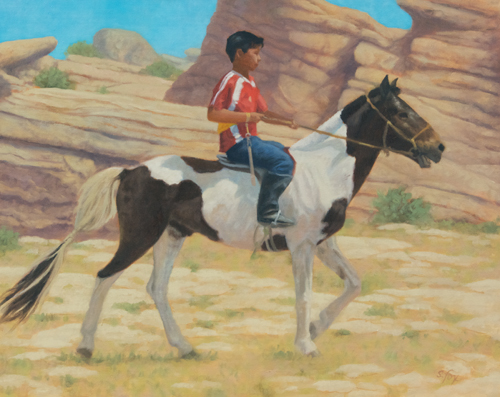

5. Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery– Housed in one of my favorite buildings, the Palace of Culture, anyone who is interested in excellent representational or abstract art will find a couple of hours here very rewarding. For a more thorough tour from my visit there during my 2009 Artists for Conservation Flag Expedition, click here. It’s clear that many of the artists have had classical training, either in Russia or other Eastern European art schools. But, as seems to be the case with most of the art forms practiced in the country, what is on display has a unique Mongol sensibility.

6. Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts– Zanabazar was one of the greatest artists to have lived and worked in Mongolia. He is best known for his exquisite bronze sculptures of Buddhist manifestations such as Tara. The best images that I was able to get, however, due to low light or glare on glass, were of some of the appliqued and embroidered thangkas, or devotional works. The Red Ger Gallery on the first floor has an excellent collection of work by contemporary Mongol artists available for purchase.