In English there are only two articles: “the” and “a”. You could bump it up to three if you wanted to to include the word “an,” which is used in the same way as the word “a” in instances when the noun starts with a vowel or a vowel sound. These are words that sometimes precede a noun to describe the “definiteness” of the noun– do you want a specific pencil, or will any pencil suffice? In German, there’s a little more to determining which article to use than just whether or not the noun starts with a vowel.

Let’s get started!

_____________________________________

Definite Articles

The most common word in the English language is the word “the.” It is used to refer to a specific noun/object, so grammarians call this this word type the “definite article.” It’s the difference between asking for any old pencil and asking for the pencil.

German has 6 different words to convey the same idea as the English word “the”: der, die, das, den, dem, des. These are known as “der words.”

According to this list, “der” is the most common German word, with “die” taking second place and “das” coming in at seventh place. Knowing this, it is important to know and understand these words and how they are used!

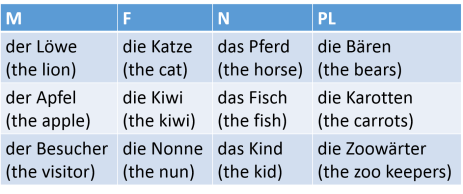

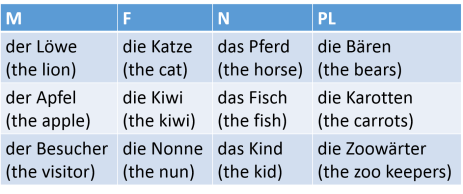

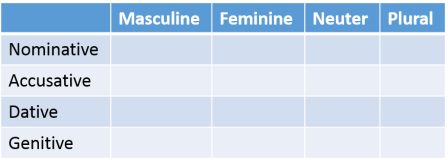

In German, every noun has a gender, be it masculine, feminine or neuter. There is a little bit of logic and reasoning behind the gender allocations, but most of them have to do with phonetics more than with traditional gender rolls and associations (For example, the word for “skirt” is masculine and the word for “necktie” is feminine). And to make matters even more complicated, pluralized nouns also have their own gender category for determining the proper article to choose.

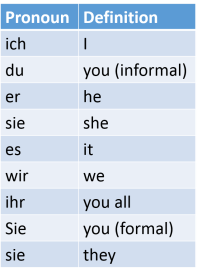

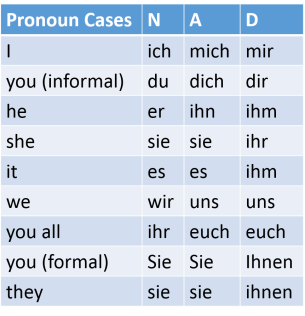

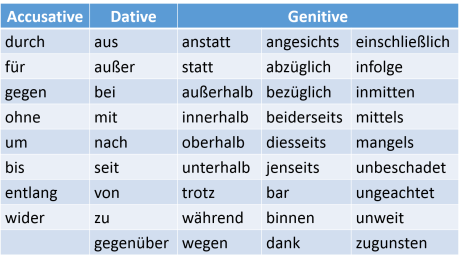

Germans also take note of the roll of the noun in their sentences and whether each noun is the subject, object, indirect object or possessed object– which are also known as being in the nominative, accusative, dative or genitive case respectively.

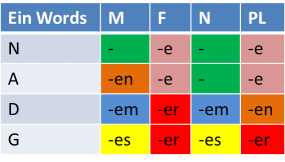

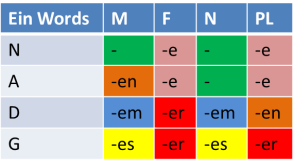

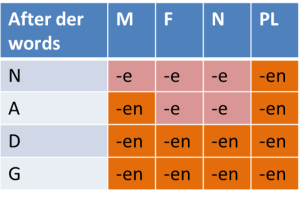

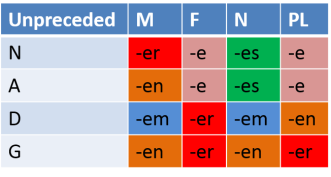

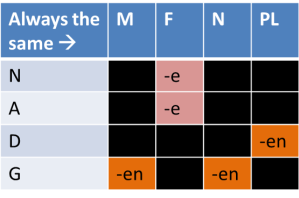

By taking these two pieces of information about each noun, you can utilize this chart to determine the correct definite article for your noun:

First, determine which column your noun’s gender dictates, and then determine the row that the noun’s case falls under. The intersection of this column and row houses your desired definite article.

I have color-coded this chart to showcase the patterns within the chart visually.

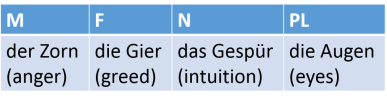

Now, for a bit of practice! Here is a pre-selected set of nouns, grouped according to gender:

We will place them in one of these pre-formulated sentences, which translates to “The _______ ate the _______ from the _______.”

- Singular subject:

- (Definite article) (Subject noun) isst (Definite article) (Object noun) von (Definite article) (Indirect object noun).

- Plural subject:

- (Definite article) (Subject noun) essen (Definite article) (Object noun) von (Definite article) (Indirect object noun).

So, if we used all masculine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Der Löwe isst den Apfel von dem Besucher.

If we used all feminine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Die Katze isst die Kiwi von der Nonne.

If we used all neuter nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Das Pferd isst das Fisch von dem Kind.

If we used all plural nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Die Bären essen die Karotten von den Zoowärter.

However, sentences will rarely be comprised of exclusively same-gendered nouns… “Die Katze isst das Fisch von der Nonne” and “Das Pferd isst den Apfel von dem Besucher” make more sense than my previous sentences. So, the quicker you get used to memorizing the forms and combining them, the quicker your German grammar will become envy-worthy!

Don’t worry, I haven’t forgotten about the genitive case! It’s just harder to incorporate into a simple sentence alongside all of the other cases, but now that you understand the 3 more common cases, we can build on what we know! Genitive case is used to express possession, much like the “-‘s” in English. If we were to translate a sentence that includes a genitive case, the genitive part usually comes out sounding like “the bicycle of the man” or “the dog of my mother”.

This time our example sentence will read: “The _______ ate the _______ of the _______.”

So, if we used all masculine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Der Löwe isst den Apfel des Besuchers. (*notice the “s” added to the end of the owner of the object.)

If we used all feminine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Die Katze isst die Kiwi der Nonne.

If we used all neuter nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Das Pferd isst das Fisch des Kinds. (*notice the “s” added to the end of the owner of the object.)

If we used all plural nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Die Bären essen die Karotten der Zoowärter.

Congratulations! You have mastered the first half of articles!

_____________________________________

Indefinite Articles

The word “a” or “an” is the 5th most common word in the English language, and its 6 German counterparts (ein, eine, einen, einem, einer, eines) rank as the 14th most common word in German.

Unlike the definite articles, these words refer to a NON-specific noun/object, so grammarians call this this word type the “indefinite article.” Now we are asking for any old pencil, instead of a specific pencil.

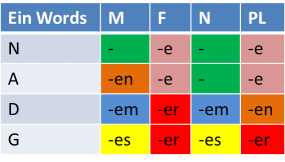

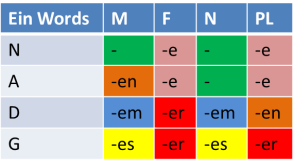

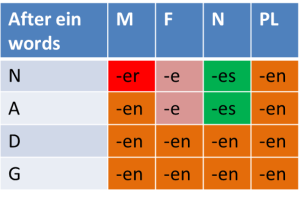

Just as before, we combine the gender of the noun and the noun’s case in the sentence to navigate to the correct “ein word.”

Again, I have color-coded this chart to showcase the patterns within the chart visually. This chart displays just the ending of the “ein word,” so orange squares are “einen“, red squares are “einer” and green squares are simply “ein.”

We will use the same example words as before to explore the indefinite articles and their changes but this time the sentence will translate to: “A _______ ate a _______ from a _______.”

If we used all masculine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Ein Löwe isst einen Apfel von einem Besucher.

If we used all feminine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Eine Katze isst eine Kiwi von einer Nonne.

If we used all neuter nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Ein Pferd isst ein Fisch von einem Kind.

Now we reach an interesting situation– we can not assign plural nouns an indefinite article (think “a bears” “a carrots” or “a zookeepers”), so I must teach you another “ein word” that is not actually an article: kein. “Kein” means “no,” in the sense of “not a one of the” or “none of the.”

If we used all plural nouns and the “ein word” “kein”, the sentence would read like this:

- Keine Bären essen keine Karotten von keinen Zoowärter.

This particular example sentence doesn’t make much sense, as there are too many negatives, so here are some other examples.

- Keine Bären essen Karotten von Zoowärter. (No bears eat carrots from zoo keepers.)

- Bären essen keine Karotten von Zoowärter. (Bears eat no carrots from zoo keepers.)

- Die Bären essen Karotten von keinen Zoowärter. (The bears eat carrots from none of the/no zoo keepers.)

Then, if we venture back into genitive, our example sentence will read: “A _______ ate a _______ of a _______.”

So, if we used all masculine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Ein Löwe isst einen Apfel eines Besuchers. (*notice the “s” added to the end of the owner of the object.)

If we used all feminine nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Eine Katze isst eine Kiwi einer Nonne.

If we used all neuter nouns, the sentence would read like this:

- Ein Pferd isst ein Fisch eines Kinds. (*notice the “s” added to the end of the owner of the object.)

If we used all plural nouns and the “ein word” “kein”, the sentence would read like this:

- Keine Bären essen keine Karotten keiner Zoowärter.

And with that, you have mastered the second half of articles!

_____________________________________

The moral of the story is that it is EXCRUCIATINGLY VITAL to learn, memorize and practice these two charts:

If you don’t get them right all the time, Germans will likely still understand you– but the longer you resist learning them, the longer you resist an “easy fix” to substantially improving your German language skills.

And there you have it! The basics of “The Awful German Language,” as Mark Twain called it.

And there you have it! The basics of “The Awful German Language,” as Mark Twain called it.