[Over his long career as a sportswriter, the Seattle-based Art Thiel rarely, if ever, disappointed in boiling down a story to its essence. This article about NBA-great Jack Sikma is no exception. Thiel’s piece, written after Sikma had retired from the NBA after celebrated stints in Seattle and Milwaukee, was published in Hoop Magazine as well as the 1997-98 New Jersey Nets Annual Magazine, where I grabbed it. Here’s to Jack Sikma. Here’s to the NBA returning one day soon to Seattle! It’s been far, far too long for a city that has already established its NBA worth.]

****

Searching for the subtleties that explain the most unstoppable basketball shot this side of the sky hook, the master paused to consider his work. “It’s not an unnatural move,” Jack Sikma said, almost professionally. “It’s a less-natural move.”

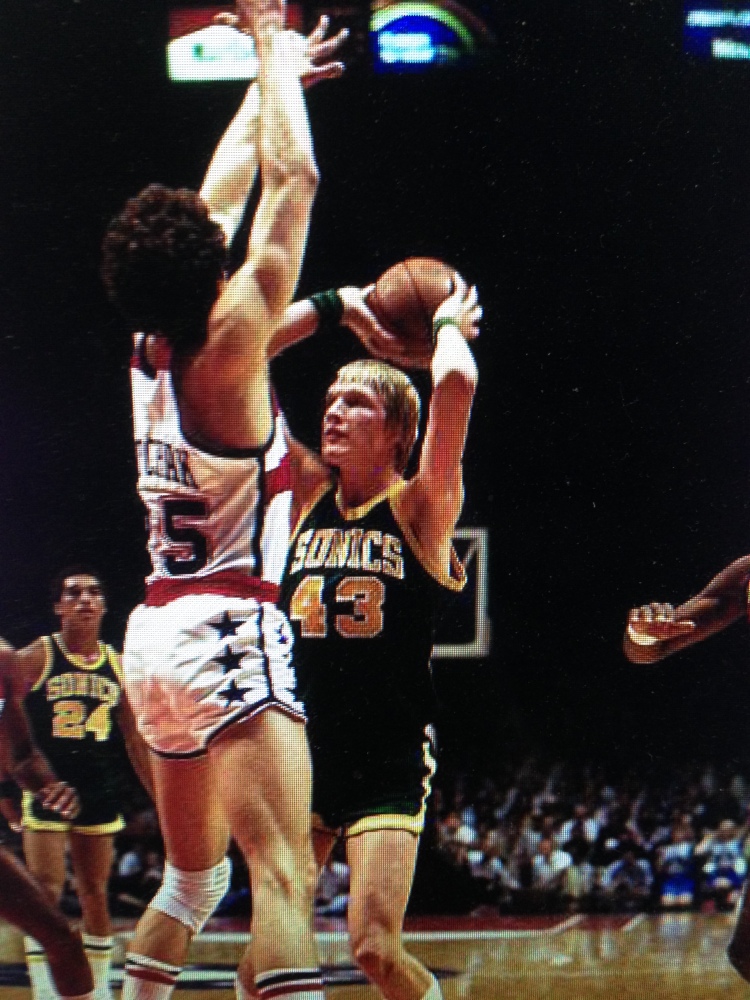

Twenty years ago, the less-natural act debuted forlornly in the Northwest, then the most off-Broadway corner of the NBA. An obscure player drafted from an even more obscure college, Illinois Wesleyan, Sikma uncranked an unwieldy maneuver full of angles, levers, and elbows that had “first-round bust” written all over it, but, in the end, changed Seattle sports history for good.

The unnaturalness started the moment Sikma got the ball. When Sikma received the ball with his back to the basket, he pivoted his body toward the defender instead of away, opening space. Then, he reset his feet with a drop step and squared to the hoop, slightly farther away from his original position, yet with clearance. For a 6-foot-11 post man, his footwork was remarkable.

Sikma scored many of his 17,287 career points using his strange shot, and it would be wonderful to say the shot changed the game. But it would also be wrong. Potent as Sikma’s inside-pivot move was—not only did it help give Seattle its lone major professional sports championship, it helped make Sikma a seven-time All-Star—no NBA player in the two decades since its pro debut has bothered to truly emulate it.

Just as the sky hook is the unique signature of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the inside-pivot remains the domain of Sikma. Or, as one of his chief rivals of the day, Moses Malone, put it in his own splendid fashion: “Everybody got to have a pet shot, and that’s Jack’s pet shot,” he mumbled. “Can’t nobody stop somebody’s pet shot.”

Malone was right. In Sikma’s career from 1977 to 1991 (nine seasons with Seattle, five with Milwaukee) defenders rarely touched his little pet. Sikma had a career average of 15.6 points a game, including five seasons averaging more than 18. He ranks 21st on the NBA’s all-time rebound list, and made seven straight All-Star teams from 1979-85.

Among those who plotted unsuccessfully against Sikma’s pet shot was Dick Motta, whose then-Washington Bullets met the Sonics in the last two Finals before the Bird and Magic era transformed the NBA. “That move is one of the few revolutionary ideas to come into the league in the last 10 years,” he said in 1982. “I challenge all of our pivotmen to learn it.”

But the revolution never came, even for players with talents similar to Sikma’s. Why? As Sikma said, it’s less natural. And in the NBA these days, if it doesn’t come naturally, it isn’t done.

“You’re not going to learn to do it on your own,” he said. “It’s something that has to be taught and worked on constantly. A lot of doubts come with it.

“The outside-pivot is natural to everyone. It’s what we do when we round a corner. Nobody makes an inside-pivot to round a corner.”

Defenders gradually learned to step up into his chest, but Sikma soon developed a ball-fake and a drive with a fast first step that made the foul a defender’s only tool—and an unreliable one at that, because Sikma was a career 85 percent shooter from the line. For added insurance against being blocked, he developed a release point far behind his head, virtually eliminating the need to jump while shooting.

The release point was the easier task. As a kid growing up in downstate Illinois farm country, Sikma was a fan of the Chicago Bulls in the era of Jerry Sloan and Norm Van Lier. Also on that team was a skinny, smooth-shooting forward, Bob Love, whose jump shots were cocked and fired from deep behind his head in the recesses of old Chicago Stadium.

As a high school sophomore, Sikma was a 6-foot-1 guard who shot facing the basket. Even at 6-foot-5 the next season, he still lopped in outside shots facing the basket and practiced the Love style of exaggerated arcs.

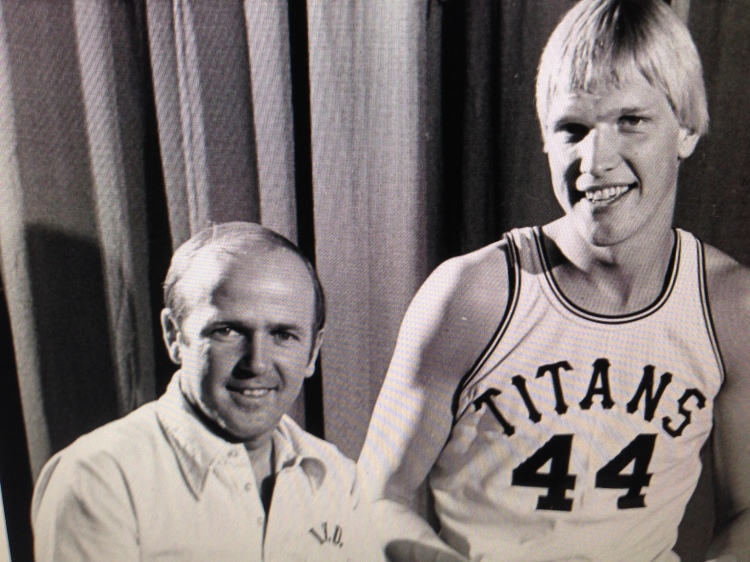

But, by the time he was a 6-foot-9 freshman at Wesleyan, then an NAIA school in rural Bloomington, Ill., not far from the family gladiola fields where Sikma worked in the summers of his boyhood, it was apparent his game was headed inside. Still a good shooter, he was neither quick nor fast, not yet strong, and no longer taller than everyone.

That’s when his coach, Dennis Bridges, stepped into his life and made Sikma step into defenders. “He made me make a commitment to the inside-pivot move, 100 at each practice, 50 on one side, 50 on the other, some with defense, some without,” Sikma said. “I didn’t have much confidence in it early, and during games, I would go away from it.

“But I can still remember hearing Dennie from the sidelines: ‘Do your move, Jack. Do your move.’”

In his sophomore year against tiny Elmhurst College of Chicago, in a high school gym so old it still had fan-shaped backboards, Sikma had his epiphany. In the second half, he made 10 field goals with “his move.”

“That,” he said, “broke the barrier.”

Bridges, who is still at Wesleyan, where he won the NCAA Division III championship last season, continues to teach the inside-pivot move, but has found relatively few with Sikma’s work ethic for the less natural.

“I later told Jack the move was designed for a clod,” Bridges said, laughing. “It allows the less-graceful big man to eliminate errors and become more effective. But it takes a lot of time and dedication to make it become natural. Remembering which foot to drop took Jack thousands of repetitions. We could skip a lot of things in practice, but we never skipped work on that move.

“If you put in the move with someone of Jack’s ability, it takes another step up in effectiveness. The thing that always impressed me with him was that he was able to adjust to the level of competition. Since he came up against taller defenders in the NBA, he learned to put his shot farther behind his head.”

Beyond the difficulty of overriding a natural tendency, Sikma sees other reasons the shot draws admiration, but not emulation. “There’s not a lot of coaches who will encourage a big man to take a step farther back to shoot,” he said, “and the change in the NBA zone rules makes it a little less effective. Teams now almost always double-team the post man with a second defender coming in from the perimeter. The inside-pivot Is designed to get the shooter to face the basket, so he automatically loses sight of where the double-team is coming from.”

At the beginning of his rookie year in 1977, Sikma didn’t have to worry about double teams. At 6-foot-11 and just 235 pounds, with straight blond hair and Dutch-boy bangs, Sikma was hardly perceived as a threat, particularly on a team that opened the season with a 5-17 record.

But after Lenny Wilkens took over as coach from the fired Bob Hopkins—the man who insisted the Sonics draft Sikma—the transformation began. Led by a superb backcourt of Gus Williams, Dennis Johnson, and Fred Brown, and grounded by veteran forwards John Johnson and Paul Silas, the Sonics won six in a row. By mid-January, they were at .500. Under Wilkens, they finished the regular season 42-18.

Because the Sonics had 7-foot-2 Marvin “The Human Eraser” Webster anchoring the middle, Sikma’s rookie year was at a more-natural power forward spot, where he averaged 10.7 points and 8.3 rebounds a game, earning the nickname “Banger.”

In the postseason, the Sonics shocked the Abdul-Jabbar-led Los Angeles Lakers in three games, ousted defending NBA champion Portland in six, then put away Denver in six in the Western Conference Finals.

The breathtaking ride ended in the seventh game of the NBA Finals when the Bullets, led by Elvin Hayes and Wes Unseld, prevailed, 105-99, in the Seattle Coliseum. But that disappointment served as a lesson well-learned.

The next year, Sikma moved into the post to replace Webster, whose loss to the New York Knicks in free agency was compensated by power forward Lonnie Shelton. The changes made the Sonics even better. Seattle became a ruthless defensive squad that won 56 regular-season games and made the Finals again, where they met the same Bullets.

This time, it was barely a contest. The Sonics won in five games as Sikma and Shelton dominated their smaller, aging counterparts, while Williams became the first guard to lead an NBA champions in scoring.

Although Sikma’s career lasted another dozen seasons, he would never return to the Finals. But the credibility gained by those two championship runs made him a permanent, prominent sports legend in the Northwest, as well as NBA history. He also has a nicknamed move invoked by 30-something and 40-something gym rats weary of having their shots blocked by younger players.

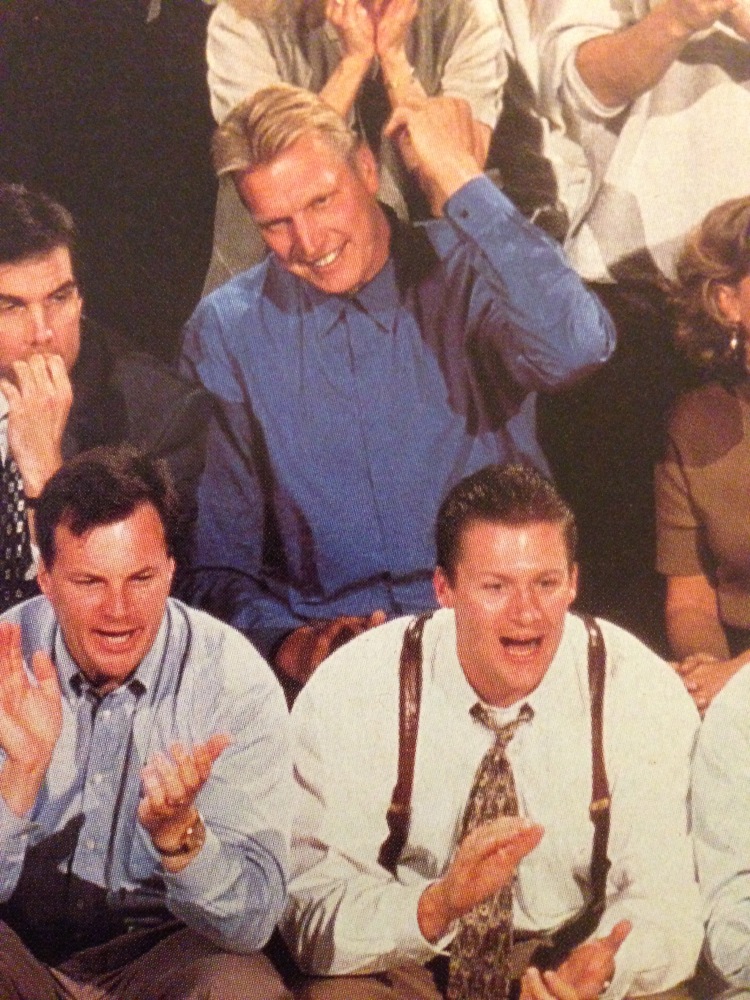

Now a golf course owner and operator with numerous other business investments, Sikma lives in a Seattle-area lakefront home with Shawn, his wife of 11 years, and their two sons. Still visible in the crowds at numerous Seattle sports events, he remains a big Sonics fan.

As the 1998 Sonics glide along at the top of the standings, darlings of the local sports scene and generators of much electricity at KeyArena, Sikma’s presence in a courtside seat is a reminder that there is a pro basketball tradition worthy of recall.

“That first year [20 years ago], we started out with so many empty seats in the Coliseum,” he said. “By the end of the season, it was raucous, it was an ‘oh-my-gawd’ experience for anybody there. When we were down by five and put on the halfcourt trap, in three minutes we’d be up by 10, and you couldn’t hear a thing apart from the crowd.

“You know how players talk about being in The Zone? We were in The Zone all year long. It was such a wonderful experience. We were pumped up all the time.”

Long before grunge, coffee, and Microsoft became Seattle pop icons, there were just the Space Needle and Sikma’s less-natural act—two vertical symbols, solitary, timeless, and unique unto themselves.

We loved Mr. Sikma in Milwaukee. Wish there would have been an image or two of him in his second NBA uniform. Thanks for the article!

LikeLike