- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE, Medicine, Surgery, Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Taking a comprehensive abdominal pain history is an important skill often assessed in OSCEs. This guide provides a structured framework for taking a history from a patient with abdominal pain in an OSCE setting.

Background

Abdominal pain is a common presentation in general practice and the emergency department. Abdominal pain has a wide range of potential causes, ranging from mild and self-limiting (e.g. constipation, gastroenteritis) to life-threatening (e.g. abdominal aortic aneurysm, ruptured ectopic pregnancy). When taking a history from a patient with abdominal pain, it is important to identify serious causes requiring urgent investigation and treatment.

Causes of abdominal pain

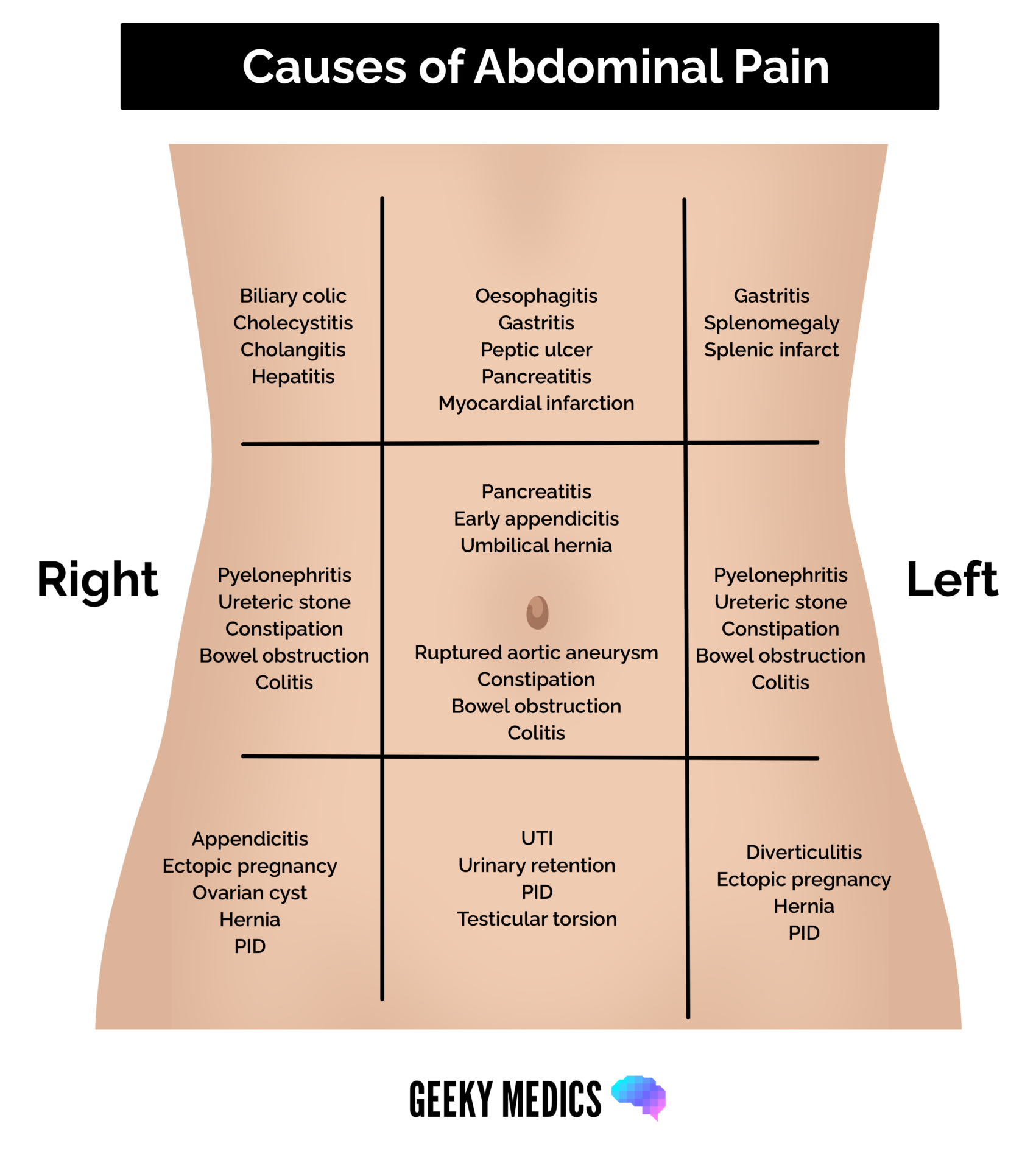

Abdominal pain has many causes covering multiple body systems, making it a challenging symptom to assess.

It can be helpful to divide the causes of abdominal pain into acute (or acute-on-chronic) and chronic and then categorise the causes by body system.

Acute or acute-on-chronic abdominal pain

Causes of acute or acute-on-chronic abdominal pain include:

- Gastrointestinal: oesophagitis, peptic ulcer (+/- perforation), gastroenteritis, splenic infarction/rupture, appendicitis, diverticulitis, bowel obstruction/ischaemia/perforation, flare of inflammatory bowel disease, strangulated or incarcerated hernia

- Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: biliary colic, cholecystitis, cholangitis, acute hepatitis, acute pancreatitis

- Genitourinary: urinary tract infection, prostatitis, pyelonephritis, testicular torsion, renal colic

- Gynaecological: ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, torsion of ovarian cyst, pelvic inflammatory disease, flare of endometriosis

- Vascular: ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Other (‘medical’ causes): myocardial infarction (epigastric pain), pneumonia (upper abdominal pain), diabetic ketoacidosis, herpes zoster, acute porphyria

Chronic abdominal pain

Causes of chronic abdominal pain include:

- Gastrointestinal: oesophagitis, malignancy (oesophageal, gastric, small bowel, colon), splenomegaly, inflammatory bowel disease, coeliac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation

- Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: malignancy (gallbladder, biliary tree, pancreatic, hepatic), autoimmune liver disorders (e.g. primary sclerosing cholangitis)

- Genitourinary: chronic prostatitis

- Gynaecological: endometriosis, ovarian cyst(s), ovarian cancer, fibroid(s), chronic pelvic pain

- Other (‘medical causes’): hypercalcaemia

Opening the consultation

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient, including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Explain that you’d like to take a history from the patient.

Gain consent to proceed with history taking.

General communication skills

It is important you do not forget the general communication skills which are relevant to all patient encounters. Demonstrating these skills will ensure your consultation remains patient-centred and not checklist-like (just because you’re running through a checklist in your head doesn’t mean this has to be obvious to the patient).

Some general communication skills which apply to all patient consultations include:

- Demonstrating empathy in response to patient cues: both verbal and non-verbal.

- Active listening: through body language and your verbal responses to what the patient has said.

- An appropriate level of eye contact throughout the consultation.

- Open, relaxed, yet professional body language (e.g. uncrossed legs and arms, leaning slightly forward in the chair).

- Making sure not to interrupt the patient throughout the consultation.

- Establishing rapport (e.g. asking the patient how they are and offering them a seat).

- Signposting: this involves explaining to the patient what you have discussed so far and what you plan to discuss next.

- Summarising at regular intervals.

Presenting complaint

Use open questioning to explore the patient’s presenting complaint:

- “What’s brought you in to see me today?”

- “Tell me about the pain you’ve been experiencing.”

Provide the patient with enough time to answer and avoid interrupting them.

Facilitate the patient to expand on their presenting complaint if required:

- “Ok, can you tell me more about that?”

- “Can you explain what that pain was like?”

Open vs closed questions

History taking typically involves a combination of open and closed questions. Open questions are effective at the start of consultations, allowing the patient to tell you what has happened in their own words. Closed questions can allow you to explore the symptoms mentioned by the patient in more detail to gain a better understanding of their presentation. Closed questions can also be used to identify relevant risk factors and narrow the differential diagnosis.

History of presenting complaint

Gather further details about the patient’s abdominal pain using the SOCRATES acronym.

Site

Ask about the location of the abdominal pain:

- “Where exactly is the pain?”

- “Can you point to where the pain is?”

The location of a patient’s abdominal pain can indicate the underlying cause:

- Epigastric pain: oesophagitis, gastritis, myocardial infarction, peptic ulcer, pancreatitis

- Right upper quadrant pain: cholecystitis, cholangitis, biliary colic, hepatitis, duodenal ulcer, pneumonia

- Left upper quadrant pain: splenic pain (enlargement, infarction, rupture)

- Right iliac fossa pain: appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, ectopic pregnancy, renal stone, mesenteric adenitis, torsion of ovarian cyst

- Left iliac fossa: diverticulitis, ectopic pregnancy, ulcerative colitis, incarcerated hernia, torsion of ovarian cyst

- Flank pain: renal colic and pyelonephritis

- Suprapubic pain: urinary tract infection, testicular torsion, miscarriage, pelvic inflammatory disease

Pain originating from abdominal organs (viscera) causes poorly localised visceral pain, as organs have fewer nerve endings. Patients may report generalised pain in the midline. The location of visceral pain depends on the structures involved:

- Foregut structures (distal oesophagus to the proximal half of duodenum): epigastric pain

- Midgut structures (distal half of duodenum to proximal 2/3rds of transverse colon): umbilical pain

- Hindgut structures (distal 1/3 of the transverse colon to the anal canal): suprapubic pain

In contrast, inflammation/irritation of the parietal peritoneum and abdominal wall causes well-localised somatic pain. The patient will be able to localise the pain well.

Example – acute appendicitis

Classically, appendicitis causes migratory pain starting in the umbilical region before migrating to the right iliac fossa.

Initial inflammation stimulates visceral afferent pain fibres, producing umbilical pain (the appendix is a midgut structure)

As the appendix becomes more inflamed, it irritates the parietal peritoneum, which activates somatic nerve fibres and produces localised pain, most often felt in the right iliac fossa.

Onset

Clarify how and when the pain developed:

- “When did the pain first start?”

- “Did the pain start suddenly or develop gradually?”

- “What were you doing when the pain started?”

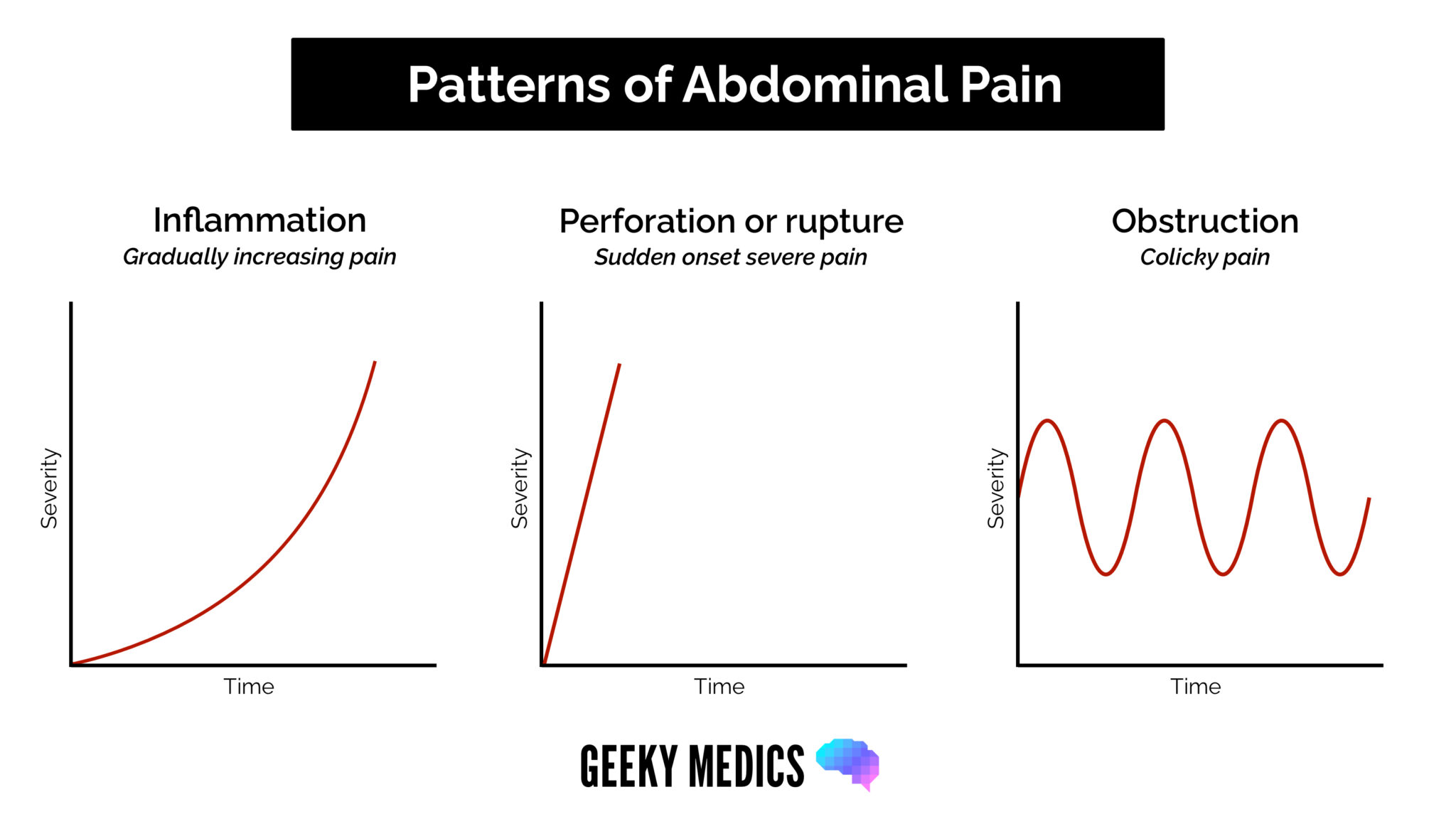

Sudden onset abdominal pain suggests a serious cause, such as perforation, rupture or torsion of an organ (e.g. ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, perforated peptic ulcer or ruptured ectopic pregnancy).

Onset over hours may suggest an inflammatory or infective cause such as appendicitis, cholecystitis or gastroenteritis.

Character

Ask about the specific characteristics of the pain:

- “How would you describe the pain, e.g. burning, stabbing, aching?”

- “Does the pain come and go, or is it constant?”

As discussed above, visceral pain causes poorly localised (generalised pain), whereas parietal/somatic pain is well localised.

Colickly pain describes severe waves of pain that come and go. An obstruction in a hollow viscus causes this type of pain. Causes of colicky pain include:

- Biliary colic (gallstones)

- Renal colic (kidney stones)

- Bowel obstruction

If a patient describes the abdominal pain as ‘burning’ (dyspepsia), this could suggest gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) or a peptic ulcer.

Radiation

Ask if the pain moves anywhere else:

- “Does the pain spread elsewhere?”

Appendicitis often starts as central umbilical pain and then radiates to the right iliac fossa.

It is also important to ask about flank/back pain, as this could be a feature of pyelonephritis or renal colic.

Pain radiating through to the back can be a feature of pancreatic pain, peptic ulcer or aortic pathology.

Pelvic pathology, such as ectopic pregnancy, may cause referred pain to the shoulder tip.

Pain from a ruptured AAA or renal colic may radiate to the groin.

Associated symptoms

Ask if there are other symptoms which are associated with the pain:

- “Are there any other symptoms that seem to be associated with the abdominal pain?”

As abdominal pain has a broad range of causes, patients may have various associated symptoms depending on the system involved.

Important gastrointestinal symptoms include:

- Fevers/chills/rigors (suggesting an infective cause)

- Nausea +/- vomiting

- Change in bowel habit (constipation or diarrhoea)

- Rectal bleeding (melaena, haematochezia)

- Mucus in stool

- Mouth ulcers (Crohn’s disease)

- Reduced appetite

- Weight loss

- Jaundice

Important urological symptoms include:

- Dysuria

- Urinary frequency

- Flank pain

- Haematuria

Important gynaecological symptoms include:

- Vaginal discharge

- Pelvic pain

- Dyspareunia

Other symptoms, depending on the cause of the abdominal pain, may include:

- Shortness of breath (myocardial infarction, pneumonia)

- Chest pain (myocardial infarction, pneumonia)

- Polyuria and polydipsia (diabetic ketoacidosis)

Each of these should be explored in more detail if present.

Time course

Clarify the time course of the pain and whether it occurs in discrete episodes or is continuous:

- “Does the pain come and go, or is it always there?”

- “How long does the pain last for?”

- “Has the pain always felt the same, or has it changed over time?”

Establishing an accurate time course of the pain can help identify the underlying diagnosis.

Chronic abdominal pain (over weeks to months) is less likely due to an acute inflammatory or vascular cause (e.g. appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, myocardial infarction). However, it could still be caused by a serious underlying cause with a more insidious onset (e.g. malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease).

Patients with chronic abdominal pain may present with an acute worsening of their pain related to disease progression or a complication (e.g. perforated peptic ulcer on the background of GORD, flare of inflammatory bowel disease).

Exacerbating or relieving factors

Ask if anything triggered the pain and if anything makes it better or worse:

- “What were you doing when the pain started?”

- “Does anything make the pain worse?”

- “Does anything make the pain better?”

Ask if the pain is affected by eating or drinking, certain positions or analgesia.

The epigastric pain caused by a gastric ulcer is usually worse when a patient eats, compared to a duodenal ulcer that worsens when the patient is hungry.

Other examples include:

- Biliary colic: triggered by eating fatty food

- Dyspepsia: worsened by laying down

- Coeliac disease: triggered by eating gluten

- Endometriosis: pain varies with the menstrual cycle

Severity

Assess the severity of the pain by asking the patient to grade it on a scale of 0-10:

- “On a scale of 0-10, how severe is the pain, if 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain you’ve ever experienced?”

Abdominal pain red flags

Red flags associated with abdominal pain include:

- Severe pain

- Persistent vomiting

- Distended abdomen associated with absolute constipation (suggests bowel obstruction)

- Unintentional weight loss

- Blood in stool

Ideas, concerns and expectations

A key component of history taking involves exploring a patient’s ideas, concerns, and expectations (often referred to as ICE) to gain insight into how a patient currently perceives their situation, what they are worried about and what they expect from the consultation.

The exploration of ideas, concerns and expectations should be fluid throughout the consultation in response to patient cues. This will help ensure your consultation is more natural, patient-centred, and not overly formulaic.

It can be challenging to use the ICE structure in a way that sounds natural in your consultation, but we have provided several examples for each of the three areas below.

Ideas

Explore the patient’s ideas about the current issue:

- “What do you think the problem is?”

- “What are your thoughts about what is causing the pain?”

- “It’s clear that you’ve given this a lot of thought, and it would be helpful to hear what you think might be going on.”

Concerns

Explore the patient’s current concerns:

- “Is there anything, in particular, that’s worrying you?”

- “What’s your number one concern regarding this problem at the moment?”

- “What’s the worst thing you were thinking it might be?”

Expectations

Ask what the patient hopes to gain from the consultation:

- “What were you hoping I’d be able to do for you today?”

- “What would ideally need to happen for you to feel today’s consultation was a success?”

- “What do you think might be the best plan of action?

Summarising

Summarise what the patient has told you about their presenting complaint. This allows you to check your understanding of the patient’s history and provides an opportunity for the patient to correct any inaccurate information.

Once you have summarised, ask the patient if there’s anything else that you’ve overlooked. Continue to periodically summarise as you move through the rest of the history.

Signposting

Signposting, in a history taking context, involves explicitly stating what you have discussed so far and what you plan to discuss next. Signposting can be a useful tool when transitioning between different parts of the patient’s history and it provides the patient with time to prepare for what is coming next.

Signposting examples

Explain what you have covered so far: “Ok, so we’ve talked about your symptoms, your concerns and what you’re hoping we achieve today.”

What you plan to cover next: “Next I’d like to quickly screen for any other symptoms and then talk about your past medical history.”

Systemic enquiry

A systemic enquiry involves performing a brief screen for symptoms in other body systems which may or may not be relevant to the primary presenting complaint. A systemic enquiry may also identify symptoms that the patient has forgotten to mention in the presenting complaint.

Deciding on which symptoms to ask about depends on the presenting complaint and your level of experience.

Some examples of symptoms you could screen for in each system include:

- Systemic: fever, weight loss or gain

- Cardiovascular: chest pain, palpitations

- Respiratory: shortness of breath, cough

- Gastrointestinal: vomiting or diarrhoea, bloating, gastrointestinal blood loss (haematemesis, melaena or fresh rectal bleeding)

- Genitourinary: polyuria or polydipsia, loin pain, menorrhagia

- Neurological: headache, sensory or visual disturbances

- Musculoskeletal: trauma, limb weakness and joint pain

- Dermatology: rashes, itching

Past medical history

Ask if the patient has any medical conditions:

- “Do you have any medical conditions?”

- “Are you currently seeing a doctor or specialist regularly?”

Ask if the patient has previously undergone any surgery (e.g. abdominal surgery):

- “Have you ever previously undergone any operations or procedures?”

- “When was the operation/procedure, and why was it performed?”

If the patient does have a medical condition, you should gather more details to assess how well controlled the disease is and what treatment(s) the patient is receiving. It is also important to ask about any complications associated with the condition, including hospital admissions.

It is important to know whether the patient has experienced similar episodes of abdominal pain before and, if so, whether they have sought medical attention. This may be reassuring if they have been investigated and received a diagnosis (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome).

However, in this situation, it is essential to maintain an open mind about the current presentation. Firstly, they may be presenting now with a new condition. Secondly, the initial diagnosis may have been incorrect, and you may be able to correct it with the new information in front of you.

Examples of relevant past medical history

Relevant past medical history for abdominal pain includes:

- Gallstone disease: patients with gallstones may experience biliary colic or develop a complication (e.g. acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis)

- Liver disease: patients with cirrhosis are at risk of decompensation

- Malignancy: previous history of bowel cancer, ovarian cancer or other relevant malignancy

- Inflammatory bowel disease: abdominal pain could indicate a flare-up or complication

- Previous abdominal surgery: can increase the risk of bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions

- History of cardiovascular disease: increases the risk of AAA, bowel ischaemia and myocardial infarction

- Hypertriglyceridemia: increases the risk of pancreatitis

Allergies

Ask if the patient has any allergies and if so, clarify what kind of reaction they had to the substance (e.g. mild rash vs anaphylaxis).

Drug history

Ask if the patient is currently taking any prescribed medications or over-the-counter remedies:

- “Are you currently taking any prescribed medications or over-the-counter treatments?”

If the patient is taking prescribed or over the counter medications, document the medication name, dose, frequency, form and route.

Ask the patient if they’re currently experiencing any side effects from their medication:

- “Have you noticed any side effects from the medication you currently take?”

- “Do you think your pain started after you began taking any of your current medications?”

Medication examples

Relevant medications in the context of abdominal pain may include:

- NSAIDs: increased risk of peptic ulcer disease, especially in patients not taking gastric protection (e.g. omeprazole)

- Ferrous sulfate/fumarate: can cause gastrointestinal upset (abdominal pain, diarrhoea and constipation)

- Opiates (e.g. codeine, morphine): cause constipation, particularly in the elderly

- Antibiotics (e.g. clarithromycin, amoxicillin, co-amoxiclav): can cause gastrointestinal side effects including abdominal pain

- DPP-4 inhibitors (e.g. saxagliptin, linagliptin): have been associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis

Patients with pre-existing gastrointestinal disease may take medications to manage their condition. For more information, see our guide to gastrointestinal history taking.

Family history

Ask the patient if there is any family history of gastrointestinal disease.

- “Do any of your parents or siblings have history of bowel disease?”

Clarify at what age the disease developed (disease developing at a younger age is more likely to be associated with genetic factors).

If one of the patient’s close relatives are deceased, sensitively determine the age at which they died and the cause of death:

- “I’m really sorry to hear that, do you mind me asking how old your dad was when he died?”

- “Do you remember what medical condition was felt to have caused his death?”

Social history

General social context

Explore the patient’s general social context including:

- the type of accommodation they currently reside in (e.g. house, bungalow) and if there are any adaptations to assist them (e.g. stairlift)

- who else the patient lives with and their personal support network

- what tasks they are able to carry out independently and what they require assistance with (e.g. self-hygiene, housework, food shopping)

- if they have any carer input (e.g. twice daily carer visits)

Smoking

Record the patient’s smoking history, including the type and amount of tobacco used.

Calculate the number of ‘pack-years’ the patient has smoked for to determine their cardiovascular risk profile:

- pack-years = [number of years smoked] x [average number of packs smoked per day]

- one pack is equal to 20 cigarettes

See our smoking cessation guide for more details.

Alcohol

Record the frequency, type and volume of alcohol consumed on a weekly basis.

See our alcohol history taking guide for more information.

Excessive alcohol use is a risk factor for liver disease and pancreatitis.

Recreational drug use

Ask the patient if they use recreational drugs and if so, determine the type of drugs used and their frequency of use.

Intravenous drug use is a risk factor for hepatitis B and C.

Diet

Ask what the patient’s diet looks like on an average day and if the patient has noticed any food category that triggers or worsens their symptoms.

A low-fibre diet and inadequate fluid intake is a common cause of constipation.

Patients with coeliac disease may report abdominal pain, nausea and diarrhoea when eating gluten-containing foods. Patients with biliary colic may report that fatty foods trigger right upper quadrant pain.

Sexual history

If appropriate, ask about the patient’s sexual history:

- Pelvic inflammatory disease can cause lower abdominal pain.

- It is important to consider ectopic pregnancy in all female patients of childbearing age

See our guide to taking a sexual history for more details.

Closing the consultation

Summarise the key points back to the patient.

Ask the patient if they have any questions or concerns that have not been addressed.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Reviewers

Dr Helen Redman

General Practitioner

Dr Lara Stewart

General Practitioner

References

- Patient UK. Abdominal Pain. January 2023. Available from: [LINK]

- Patient UK. Acute Abdomen. August 2019. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Cholecystitis. July 2021. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE CKS. Cirrhosis. June 2018. Available from: [LINK]

- Boon, NA. Colledge, NR, Walker, BR (eds). Davidson’s Principles & Practice of Medicine 20th Ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2006

- NICE CKS. Appendicitis. May 2021. Available from: [LINK]