A new report from the Congressional Budget Office hasn’t received wide coverage, so far but may become an important resource for journalists in the coming months if Democrats in the U.S. Congress seek to increase competition in health insurance markets nationwide. It also could be a useful resource if any state seeks to develop a public option.

In “A Public Option for Health Insurance in the Nongroup Marketplaces: Key Design Considerations and Implications,” the CBO notes that some members of Congress have proposed a federally administered public option that would become a health insurance plan. That public-option plan would compete with commercial health insurance plans in the nongroup marketplaces established under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), as the report explained. During the presidential primary last year, some Democrats — including now President Joe Biden — proposed a public option as an alternative to a single-payer insurance model known as Medicare for all.

Before getting into the report’s details, it’s important to consider why this report would be useful for journalists. First, it will be helpful because it focuses on the individual market, which is different from the group market where employers and other large organizations buy coverage for workers and group members.

Those group members get insurance at lower rates because insurers can spread the risk among all policyholders. Individuals fall into the nongroup market because they cannot buy coverage through the group market except under certain circumstances, such as a job loss when continuation coverage could be an option under federal law.

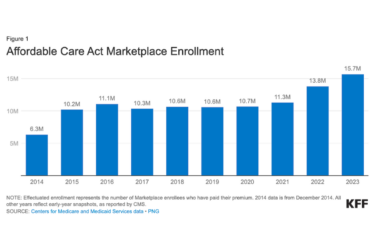

In the individual market, consumers can shop for plans at HealthCare.gov or in the ACA exchanges in their states. The problem for consumers is that competition among insurers is limited in almost three-quarters of all individual markets because those markets are considered highly concentrated, according to a report last year from the American Medical Association.

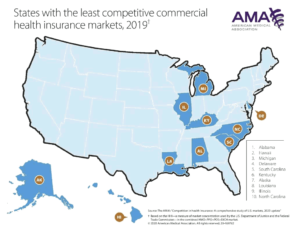

In that AMA report, Competition in Health Insurance: A Comprehensive Study of U.S. Markets, researchers cited data from the previous year on the degree of competition in commercial health insurance markets. In highly competitive markets, consolidation among health insurers could harm consumers and health care providers, the AMA report noted. Last year, we reported on the importance of this annual report for health care journalists.

The AMA’s researchers also showed that 284, or 74% of health insurance markets in the United States (which the AMA described as metropolitan-statistical areas or MSAs) were highly concentrated in 2019, an increase of three percentage points over what the AMA reported in 2014.

In 2019, the 10 states with the least competitive health insurance markets were Alabama, Hawaii, Michigan, Delaware, South Carolina, Kentucky, Alaska, Louisiana, Illinois and North Carolina, the report noted. These 10 states bring us to the second reason the CBO report is important. In any one of those states, the legislatures could move to develop a public option, as Connecticut did last year. What happened in Connecticut is instructive because any proposal to develop a public option would generate stiff opposition from health insurers that already operate in the individual market.

In Connecticut last year, state officials proposed a public option to compete with commercial health insurers, as Shefali Luthra wrote for Kaiser Health News. Her article carried this headline, “Insurers Sank Connecticut’s ‘Public Option.’ Would A National Version Survive?” Luthra has since moved on to write for The 19th News, an independent nonprofit.

Members of the Connecticut legislature proposed a public health insurance option that state officials would manage because health insurance and coverage costs were becoming unaffordable, Luthra wrote. The public option would serve as a low-cost alternative for those who couldn’t afford to buy health coverage from commercial health insurers, she added.

“Immediately, an aggressive industry mobilized to kill the idea. Despite months of lobbying, debate and organizing, the proposal was dead on arrival,” she explained.

All this serves as a preamble to the CBO report itself. At the website Benefits Pro, Allison Bell reported that the CBO researchers outlined the choices policymakers could consider when designing a public option, and how those choices could affect the health insurance market.

If the public-option plan has significant competitive advantages, for example, those advantages could make it difficult for private insurers to remain profitable, the report noted. Therefore, health insurers would surely fight any public option, in part because the nation’s largest health insurers are publicly traded companies. That means they focus closely on how much profit they report each quarter to Wall Street investors.

If any public-option health plan is not required to meet the benefit mandates that states require, or if the plan pays hospitals and physicians Medicare rates that, as we reported in September, are much lower than what commercial health insurers pay, then competing commercial health plans may struggle. They could have trouble retaining enough market share and keep their premiums high enough to justify staying in the markets where they currently participate, the report indicated. In other words, a public-option health plan could drive commercial insurers out of a particular market.

The report describes the key factors for those designing a public-option plan and some implications of those factors, Bell reported. She explained that some of those key factors are:

- How the public option is funded

- How and whether the public option conforms to state health insurance regulations

- How well the benefits and prices of the public option conform to the benefits and prices in the market

- How the public option recruits and pays hospitals, physicians and other providers.