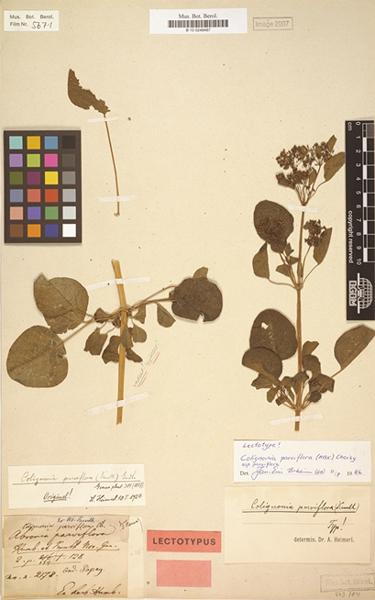

Abronia parviflora collected in Columbia by Humboldt and Bonpland, specimen in the herbarium of Berlin-Dahlem Botanical Garden.

A few years ago, Andrea Wulf (2015) published The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. “New World” here can be interpreted two ways: as the Western Hemisphere that Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland explored during their famous five-year expedition (1799-1804), and as the world through new eyes made possible by Humboldt’s writings that influenced such leaders of environmental and ecological thinking as Henry David Thoreau, George Perkins Marsh, Ernst Haeckel, and John Muir. It is because of this impact that Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), born 250 years ago, deserves attention today. It seems appropriate to dedicate this series of posts to someone who helped shape the way we look at plants now. I’ll begin by discussing early influences on his thinking and the general arc of his life’s work. The following posts will deal more specifically with aspects of his botanical studies.

Humboldt was born into a upper-class family in Berlin. His father died when he was 10, leaving him and his older brother Wilhelm in the care of their rather aloof mother who aimed to have her sons well-placed in the Prussian establishment. From an early age Humboldt exhibited other inclinations, especially an interest in natural history, collecting specimens and creating what amounted to a museum of his finds. To learn more about plants, he took some of his specimens to Carl Ludwig Willdenow, an apothecary who had just published a flora of Berlin. This meeting led to Willdenow becoming Humboldt’s botany tutor. While his mother hired Willdenow, this didn’t divert her from her plan, so Humboldt studied finance for a brief time and then went to the University of Gottingen where his brother was also enrolled. There he met George Forster who years before had travelled with his father on Captain James Cook’s second circumnavigation. Forster became Humboldt’s mentor, and like many among the educated elites of the time, they made a grand tour, visiting the Netherlands, France, and England. This broadened Humboldt’s horizons, to say nothing of his knowledge of natural history. In England alone, he met Joseph Banks, James Edward Smith of the Linnean Society, and the Oxford botanist John Sibthorpe.

After this trip, Humboldt studied more seriously, enrolling in the Freiburg School of Mines. Upon graduation in 1792, he was appointed a mine inspector, a Prussian government position to his mother’s satisfaction. He threw himself into his work, which was great preparation for his future travels (Anthony, 2018). Humboldt became familiar with the new ways of illustrating rock formations that were beginning to emerge and with the plants growing in the subterranean world of the mines. In fact, he wrote Florae Fribergensis in 1793, describing the plants, algae, and fungi he encountered. As part of his work, he made a tour of mountainous areas in Switzerland and Italy, focusing on geology and botany. His mother died in 1796, freeing him from having to remain in government service since he and his brother inherited significant wealth. Within a year, Humboldt prepared to leave Prussia and do some serious exploring of distant lands. He headed for Paris, where he met Louis-Antoine de Bougainville who was planning a naval expedition and invited Humboldt to join. Nothing came of this, but in the meantime, he had met Aimé Bonpland, a botanist who had been educated by Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and René-Louiche Desfontaines at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.

Humboldt and Bonpland got along well and both were interested in exploration. After further efforts to join a French expedition failed, they headed to Spain where they convinced the King to issue them passports to Spanish-held lands in South America and also the Philippines. Since Humboldt was funding the trip, the King had little to lose and much to gain in terms of new knowledge about his own lands. Humboldt had amassed an impressive array of the latest equipment for carrying out astronomical, meteorological, and geological measurements. His gear also included supplies for collecting specimens, but as can be seen by just this brief review, their trip was rather ad hoc and remained so throughout. The first stop was Tenerife, where they climbed the island’s Mount Teide. They were thrilled with the experience and tested out their instruments for measuring altitude, atmospheric pressure, etc.

When they landed at Cumaná in what is now Venezuela, they spent over a year exploring including traveling the length of the Casiquiare River that forms a natural canal between the Amazon and Orinoco Rivers (Helferich, 2004). They then sailed to Cuba before returning to South America and climbing in the Andes. They went on to Lima, up the west coast to Ecuador and by sea to Mexico where they spent a year before sailing back to Cuba and to the United States. At several points during the voyage they had to recalculate their plans, and they never did get to the Philippines. By the time they left Mexico, Humboldt was anxious to return to Europe to start writing up his findings and learn the latest news in science because he had been out of touch for so long. Humboldt and Bonpland settled in Paris since the scientific climate there was most conducive to doing the research necessary to describe their observations and specimens. After this voyage, Humboldt never returned to the New World, though he did make one major trip later in life through Russia to Siberia to advise the Tsar on his mining interests there. In the next post, I’ll discuss Humboldt’s and Bonpland’s botanical collections from the Americas and how they were eventually sorted out.

References

Anthony, P. (2018). Mining as the working world of Alexander von Humboldt’s plant geography and vertical cartography. Isis, 109(1), 28–55.

Helferich, G. (2004). Humboldt’s Cosmos. New York, NY: Penguin.

Wulf, A. (2015). The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. New York, NY: Knopf.