Disclaimer: These essays presume you’ve seen the film in question. If you want to avoid spoilers, watch the movie first!

Everyone has to end somewhere.

Family Plot (1976) is Alfred Hitchcock’s last feature film, his fifty-third, and the capper to a career that started in the 1920s. It’s worth taking a moment to comment on how rare that kind of longevity is, especially in notoriously tumultuous Hollywood. For instance, in 1972 Hitchcock was one of several filmmakers to attend a luncheon at George Cukor’s house in honor of Luis Buñuel, and the gathering (with accompanying photo) has become legendary. Of the filmmakers there, only Hitchcock and Buñuel had started in the silent era and were still making films. Four years later, Hitchcock would begin filming Family Plot.

Sure, Family Plot is not a great film, especially when viewed against Hitchcock’s other masterpieces. Yet it’s also a wonderfully charming, off-kilter lark that shouldn’t be compared to Hitch’s towering achievements in suspense. Family Plot isn’t trying to be a white-knuckle thriller; instead its the kind of movie that correctly assumes there’s a certain charm in watching Bruce Dern smoke a pipe and stumble around a cemetery.

More than any other Hitchcock film, even the New Hollywood/Antonioni-influenced Frenzy, Family Plot is Hitchcock trying something different. He told screenwriter Ernest Lehman (who had written North by Northwest as well as The Sound of Music and West Side Story) that he wanted the film to be a light, playful Ernst Lubitsch-inspired caper. Yet while the film is decidedly more playful than what you might expect from Hitchcock, it’s purely a product of the 1970s. Whether by design or age of its director, Family Plot showcases little of the Master’s unparalleled visual dexterity. In some passages it approaches the ramshackle charms of Robert Altman’s best work, especially in the off-kilter scenes with Bruce Dern and Barbara Harris. And perhaps not coincidentally, Robert Altman got his start directing TV shows, including several episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

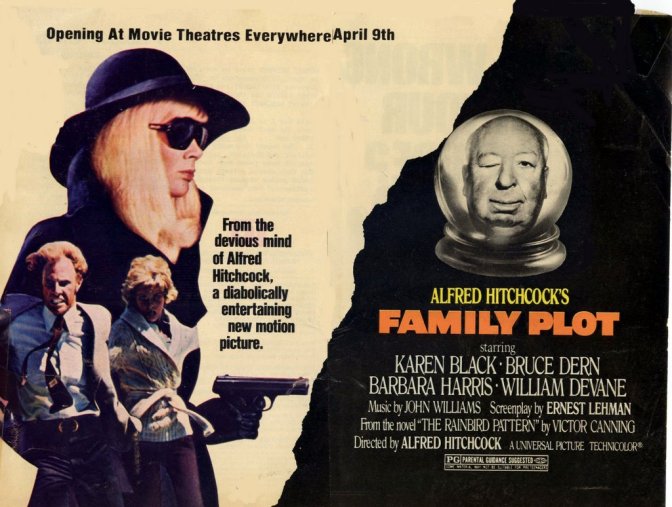

The film is more a classic mystery than suspense thriller. It opens with Harris providing spiritualist services to an old woman who wants to track down her long-lost nephew to let him inherit the family fortune. It’s unclear if Harris is a fraud or if she believes herself a true psychic, but her boyfriend Bruce Dern isn’t having it. In a terrific comic performance Dern plays a cab driver/actor who does Harris’s dirty work, pretending to be a lawyer and private eye who gets sucked into the case. Meanwhile William Devane and Karen Black (iconic in a blonde wig, sunglasses, hat & matching black trenchcoat) play a couple of master kidnappers who abduct and hold people in their secret garage holding cell. The kidnappers and the “psychics” wind their way through two separate plotlines that slowly start to intersect before resolving in a final confrontation.

This is a film that is light on big setpieces (what Hitchcock is best known for) and heavy on long rambling conversations with Bruce Bern & Barbara Harris. I imagine that in the scripting stage the two couples were more clearly aligned as a ying/yang situation. But Hitchcock adored both Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern (while Devane replaced the too-method Roy Thinnes several days into shooting and Karen Black struggled to connect with Hitch). Dern had already acted in Marnie (1963) and showed up over the years in several Alfred Hitchcock Presents. By all accounts, it seems that Hitchcock let Harris & Dern improvise and add things on set, which is a remarkable sentence to write.

This is HITCHCOCK we’re talking about. The man who said that “actors are cattle” (he meant it as a joke, but it’s not far from his behavior). Aside from Stanley Kubrick, the most visually demanding director in Hollywood. Yet Bruce Dern actually loved the combination of freedom and control that Hitchcock gave him in the film. Hitchcock demanded that an actor start a scene on one mark and end in another, but in between how they got there was entirely up to them. So Dern did his best to chew the scenery, with mixed results.

When it works, it’s terrific. Dern bumbling around pretending to be a lawyer or Harris putting on ridiculous “spiritualist” voices to fool gullible old ladies is a delight. At times Dern comes off like a second cousin to Elliott Gould’s Philip Marlowe in Robert Altman’s revisionist masterpiece The Long Goodbye. But at Dern & Harris’s worst, it’s awful. Take the long, long, so very long scene where the duo drive down a mountain road with their brakes cut, heading out of control. This is Hitchcock 101, a scene we’ve seen variations of in North by Northwest, Suspicion, and many more.

Yet this is excruciating to watch. This is 1976, when cinema has gotten used to car & highway scenes like the ones in Bullitt, Easy Rider, or Two Lane Blacktop. Watching sped-up footage point-of-view footage and Dern & Harris overacting and playing for broad laughs against a rear-projection screen is downright painful.

The film suffers in other ways too; Hitchcock’s remarkably keen visual style is sometimes blunted by the use of too many zoom lenses, which I have to attribute to ease of production. Using a zoom lens means fewer setups and less time on location for the 76 year old man who’s driven to a few feet from his director’s chair every day. At times Family Plot resembles a long episode of The Rockford Files in its flat matter-of-fact lighting and easygoing charm (sidenote: I love The Rockford Files).

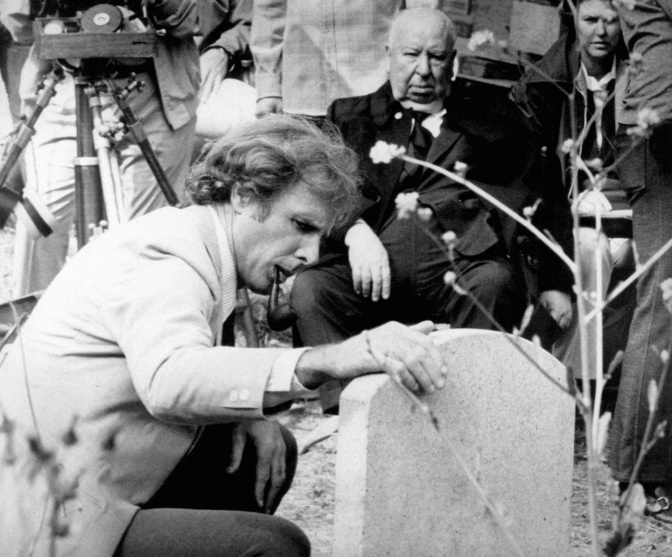

There is one brilliant cinematic moment (well actually two, but we’ll talk about that second one later), when Dern is playing sleuth at the funeral of a man who tried to kill him. The man’s widow sees Dern and tries to leave, picking her way through the overgrown weeds of a small country cemetery. Hitchcock cuts to a massive overhead shot showing all the paths in the cemetery and we watch as Dern heads her off at every pass, slowly closing in the geometry of her escape, until she must face him. It’s an effective yet undoubtedly complex shot.

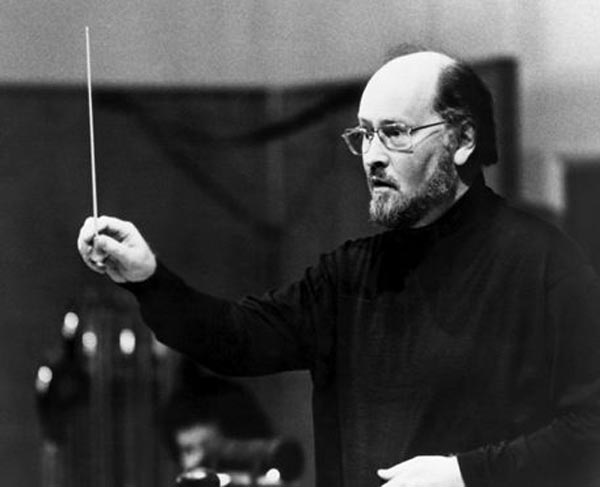

One of my least favorite parts of the film is the score. Hitchcock never reteamed with Bernard Hermann after their falling out (Hermann died in 1976 after finishing the score to Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver), and this cloying, overwritten soundtrack is a pale rehash of Hermann’s best motifs (the Wagnerian water music themes of Vertigo and the stabbing strings of Psycho). Even worse there’s a persistent, inexplicable harpsichord noodling along, just to remind you that it’s the Seventies. What hack wrote this garbage? What plucked-from-obscurity studio head’s cousin that he could handle this garbage? Since there are almost no credits at the beginning of the film, I had to wait to the end to discover that the score was written by JOHN WILLIAMS.

Yep. John Fucking Williams. John “Jaws, Star Wars, Superman, Indiana Jones, Jurassic Park, Harry Potter, 50 Academy Award nominations” Williams.

That said, I stand by my opinion. This score is awful, but I’m sure Williams delivered what was asked of him. Family Plot was a prestige assignment and Williams was the golden boy at Universal after his game-changing work on Jaws (1975). So maybe the fault doesn’t lie with him.

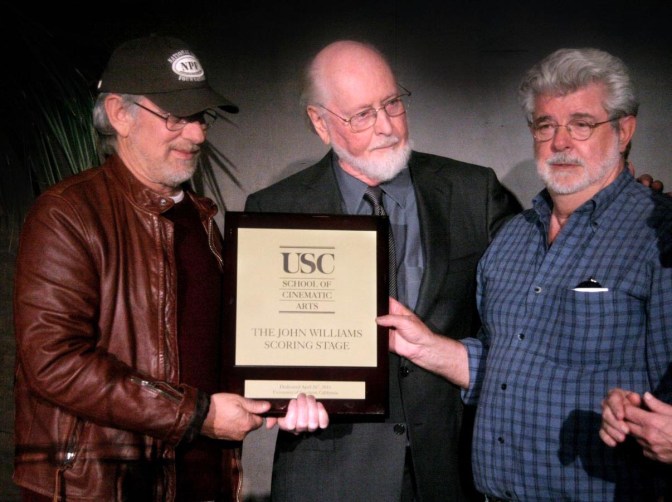

This is probably not a surprise to anyone, but I was a bit of a nerd in high school (no, really!). I was already into classic movies, but I was also obsessed with Star Wars and Jurassic Park and Indiana Jones, and basically everything that John Williams scored for Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. Star Wars wasn’t the cultural force that it is now either. The trilogy was a household name and the highest grossing series in existence, but it was still felt nerdy to like it. Or maybe it was nerdy to obsess over it the way I did.

As a teenager my dad took me to a screening of all three Star Wars films, probably in 1989 or 1990. This was before the special editions, before the prequels, when the movies were projected in a theater by the University of Arizona film club and the place was packed with college students and dads with their kids. John Williams does a brilliant thing with these films, where he incorporates the 20th Century Fox fanfare into his score, creating a rolling crescendo that continues through the studio credits, then dips down into a twinkle during “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” before finally bursting into full force as the words “Star Wars” flash onto the screen. It’s electrifying to see on a big screen.

That remains one of my favorite movie-going experiences. It had the thrill of seeing the movies on the big screen (I believe I sad Return of the Jedi in its initial 1983 run but had to leave the theater because the Rancor scared me), but so much else was going on too. Could I stay awake for all three films (over seven hours plus breaks between the films)? And that special feeling you get as a teenager when you’re doing something with older people; that you’re in on it too, you’re an adult. You get it, man. I’ve come close to that moviegoing high other times (seeing Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman opening weekend comes to mind) but I don’t think I’ll ever experience anything that special again.

Some critics accuse Williams of being too loud, too bombastic, too catchy, but I think his work (Family Plot excepted) perfectly matches the movies he’s scoring. Is there a better expression of the best of all humanity than his instantly recognizable Superman theme? He paints in broad strokes when the movies demand it; for a smaller film, like Spielberg’s underrated Catch Me If You Can, Williams went back to his jazz roots for a subtle score (sidenote: Williams, a classically & jazz trained pianist, not only played on numerous Henry Mancini scores, including the Peter Gunn theme, but his first credit as composer is on the MST3K classic Daddy-O).

It feels like John Williams wrote the score for my childhood. As a kid in love with the movies, it was a great time to hear those rousing scores. Every time I hear them it takes me back to the first time, how those movies transported a young kid who sometimes had trouble relating to others and was scared of girls. How it made me thrill to and delight in the possibility and promise and romance of cinema. It’s part of why i still love movies, and why I’m sitting outside on a warm spring night now, typing away into my laptop about Hitchcock and John Williams.

***

A big question around Family Plot is whether Hitchcock knew this was his last film. The easy answer is no, of course not. Hitchcock remained in development on a spy thriller, The Short Night, for years and in interviews for Family Plot was happy to claim that he was busy at work on a new project.

And yet. His health was failing him (to say nothing of his wife Alma’s). Hitch’s dark sense of humor would lead him to eagerly display his pacemaker to everyone, and even held up William Devane’s first day of shooting so he could phone his doctors, who listened over the phone to the pacemaker’s rhythm to check the battery life.

Surely Universal had clues that this might be the Master’s last film. The studio went all out for a press launch on the first day, inviting reporters to the film’s cemetery set where numerous fake tombstones had critic’s names on them. The premiere was a gala, black-tie affair. Universal knew that this wasn’t the Hitchcock of old, they’d seen the dailies and the final film, yet their press and marketing for the film made it seem like a victory lap, the capper to a legendary career.

And finally there’s two moments in the film itself. When shooting, Hitchcock still hadn’t decided on where to do his cameo, if he wanted to do it at all (in previous films, Hitch always planned his cameo for early in the film so the audience wouldn’t be looking for him the whole picture). Bruce Dern egged Hitch on, saying that he had to do a cameo, he just had to. Hitchcock relented, in a way, showing up halfway through the film only as his famous silhouette, backlit behind a frosted glass door that reads “Registrar of Births & Deaths.” If Hitchcock was hinting towards his own mortality, he couldn’t have done a better job than with this cameo.

For me, this second instance is the more telling moment. At the end of the film, after the kidnappers have been vanquished and locked in their own cell, Barbara Harris experiences a moment of genuine psychic ability. This alone is rare in Hitchcock; while his movies occasionally rely on coincidence or invoke ghostly and supernatural moments, they’re always shown to be man-made later (moments in Jamaica Inn, the dead wife in Rebecca, the hallucinations in Under Capricorn). Yet this is a full-on, unexplained moment of clairvoyance, as Harris walks through the house, guided by spirit “Henry,” directly to where a gigantic jewel is hidden in the chandelier.

It’s a singularly British moment, an embracing of village ghost stories that Hitchcock grew up with and spent much of his career subverting. But the final shot is the key. Dern rushes off to call the police. Harris watches from the stairs, then smiles, looks directly at the camera, and winks.

She winks! Right at us! I’m still rewatching all of Hitchcock’s films, but I’ve never seen him break the fourth wall. Yes, Anthony Perkins looks at the camera at the end of Psycho, but that’s a character moment of insanity, not a literal wink at the audience. You could make the case that Hitchcock’s entire career is him playing with the audience, winking at them metaphorically with his breezy implausibility, suspense, MacGuffins, and bag of tricks.

Yet Hitchcock breaking the fourth wall, in classic Bugs Bunny “Ain’t I a stinker?” fashion, is unprecedented. I suppose you view this as the indulgence of an old man, a director who loved his lead actors and let them have their fun, regardless of the consequences. But I think it’s more than that.

Hitchcock knew that his body was falling apart. He saw it in himself and he saw it in his wife. He saw the movie industry changing around him, even as he tried to change and adapt with it. Hitchcock didn’t officially announce his retirement until 1978; he kept reporting to his bungalow on the Universal lot and working on The Short Night, but I think his heart wasn’t in it. I think deep down, he knew.

And what could be a more fitting coda? Sure, we’d all love it if Hitchcock had gone out in a blaze of glory, making one last masterpiece, vaulting The Short Night to the top of all the Hitchcock Best-Of lists. But I’ve read the script and we know what kind of state Hitchcock was in. I doubt he could have even made the film, let alone made it great.

So instead we have the ending of Family Plot, a not-great but awfully fun film full of quirks, humor, and lovely touches. The final image of beautiful blonde Barbara Harris winking at us as if to say, “It’s all a gag. It’s all in fun.” In the end, after all the jokes, dark humor, countless thrills, pulling the rug out from audiences time and time again, maybe it really is as simple as Bugs Bunny. “Ain’t I a stinker?” as spoken by the Master of Suspense.

Watch It: Family Plot (1976) is not available on any streaming services (Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime, HBO). It is available to rent or buy on iTunes or Amazon Prime, and can be found at almost any existing rental store or library collection.