Chapters

Septimia Zenobia was the wife of the king of Palmyra – Odenatus, after his death in 267 CE, she tried to strengthen the position of her underage son Vaballat. Initially, she sought an agreement with subsequent emperors.

Ultimately, however, thanks to a skilful policy, Zenobia led to a strong expansion in the region and enjoyed full power in the eastern territories of the Roman Empire.

Origin and family

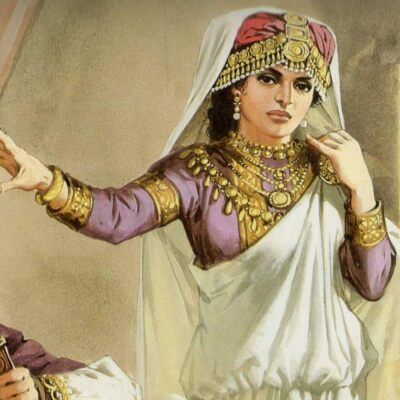

Her face was dark and of a swarthy hue, her eyes were black and powerful beyond the usual wont, her spirit divinely great, and her beauty incredible. So white were her teeth that many thought that she had pearls in place of teeth. Her voice was clear and like that of a man.

– Historia Augusta, 30.15-16

The exact date of Zenobia’s birth is unknown, but it is believed that it was around CE 240. Her Roman name was Julia Aurelia Zenobia. In turn, the girl’s Palmyra name is Bat-Zabbai (spelled “Btzby”, which meant “Zabbai’s daughter”). On a daily basis, however, she used the name Zenobia, which meant “the one that comes from Zeus”. The nineteenth-century historian al-Tabari, who, however, often missed the truth in his accounts, claimed that the name of the queen was Na’ila al-Zabba. ‘ In contrast, Manichean sources call it “Tandi”.

Palmyra’s society consisted of Semitic tribes (mainly Arab and Aramaic), and Zenobia cannot be identified with any of these groups. As an inhabitant of Palmyra, she could have had both Aramaic and Arab ancestors. Information on this subject is sparse and contradictory. Nothing is known about her mother, and her father’s identity continues to be debated among historians. Zenobia herself believed that she was of direct lineage from the Ptolemaic dynasty and that she was a descendant of Cleopatra, but there is no certain evidence of this. Manichean sources mention that a certain “Nafsha” was the sister of “Queen Palmyra”, but the information is unclear and “Nafsha” may be Zenobia’s literary name as it is doubtful that she would have a sister.

The Story of Augustus details Zenobia’s early life in detail, although the credibility of this source is questionable. According to its content, the queen loved to hunt since childhood. Apparently, she had to come from the Palmyra aristocracy, for she had received an education appropriate for elite girls. According to the History of Augustus, in addition to her native Aramaic, she was also supposed to know Egyptian, Greek and even Latin. When she was about sixteen, she became the second wife of Odenatus, ruler of Palmyra. Little is known about the relations between the spouses, but Zenobia treated her husband quite “objectively”, primarily seeking to beget heirs:

For when once she had lain with him, she would refrain until the time of menstruation to see if she were pregnant; if not, she would again grant him an opportunity of begetting children.

– Historia Augusta, 30.12

The queen’s “endeavors” proved fruitful as she eventually bore her husband several sons and daughters.

Death of the husband and self-rule on behalf of the son

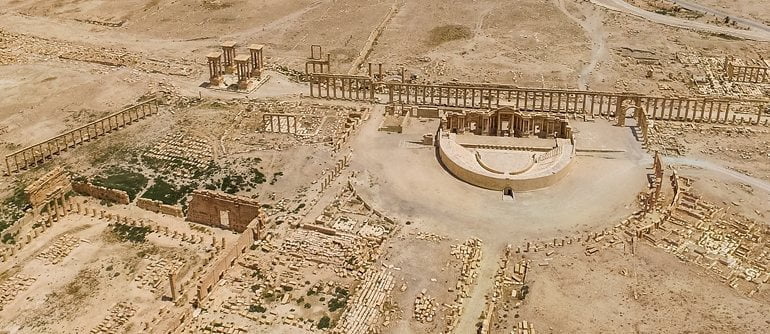

In the first centuries CE, Palmyra was a city subordinated to Rome and part of the province of Phenicia. In 260 CE, the Roman Emperor Valerian marched against the King of Persia, Shapur I, who invaded the eastern regions of the Roman Empire. Valerian, however, was defeated at the Battle of Edessa and taken prisoner. Odenatus remained loyal to the Roman Emperor Galien (son of Valerian), for which he was awarded the title of King of Palmyra. Thanks to his successes in the war against Persia, he was crowned King of the Kings of the East in 263 CE. Odenatus crowned his eldest son, Herodos, from his first marriage, whom he made co-ruler. In addition to the royal title, Odenatus received many honours from Rome. The most important, however, was the title “corrector totius orientis”, ie the governor of the entire east, thanks to which he ruled the Roman territories from the Black Sea to Palestine.

In 267, when Zenobia was about 20-30 years old, Odenatus and his eldest son were murdered on their return from a war expedition. According to The Story of Augustus, Odenatus was murdered by his cousin Meonius. The same source states that Zenobia conspired with Meonius and plotted the murder of her husband because she wanted Palmyra to be ruled by her own sons and not her stepson, but she does not blame Zenobia herself directly. The “Historia Augusta” also adds that Meonius murdered his cousin because of jealousy, lust for power and his own moral degeneration.

The first records that define Zenobia as the queen of Palmyra come from several years after her husband’s death. It is not known when exactly she started using this title, but probably from the same day her husband became king, however, she herself, as the king’s consort, remained in the background and was not mentioned in historical sources. Later sources mention that she accompanied her husband on military expeditions, boosting the morale of the soldiers and gaining the political influence that was needed in her later career.

The History of Augustus records that Meonius briefly proclaimed himself emperor before he was murdered by his own soldiers, although there is no evidence of his reign. Zenobia, on the other hand, was able to be at her husband’s side at the time of his death. According to the chronicler, Jerzy Synkelos, Odenatus was murdered in the vicinity of Pontic Heraklea. The handover had to be smooth, as Synkelos claimed that one day had passed from Odenatus’ death to Zenobia being made queen by the army. Zenobia could have been in Palmyra, but then she would have had problems with taking power, because the army could choose one of the generals asking. Historical records agree that Zenobia did not fight for power. Nor is there any evidence that she handed over power to her son, ten-year-old Waballat, although she has never admitted to ruling alone and has officially acted as her son’s regent. Zenobia exercised actual power in the kingdom, and Wabbalat remained in the shadow of his mother and never exercised his own rule of power.

The Palmyra monarchy was a new form of power and its allegiance was based on loyalty to Odenatus, which made it more difficult to transfer power to an heir than it would have been for an established royal dynasty. Odenatus tried to ensure the continuity of power by crowning his eldest son as co-ruler, but both were murdered. Zenobia, in order to secure the continuity of the succession and ensure the loyalty of his subjects, announced that her and Odenatus’ son, Waballat, was heir to his father and assumed his royal titles, and the earliest known inscription describes him as King of Kings.

Odenatus controlled much of the Roman East and had the greatest authority in the region, both politically and militarily. In this respect, he even surpassed some local Roman governors. His self-proclaimed status was confirmed by Emperor Galien, who had no choice but to agree to it. Odenatus’ rule, compared to that of the imperial one, was unprecedented and flexible, but their relations with each other continued well until the death of the king. However, his death meant that the authority and position of Palmyra’s rulers had to be reaffirmed, leading to a conflict over who the power belonged to. The Roman court considered Odenatus a Roman official whose power came from the Emperor, but the Palmyra court considered his authority to be hereditary. This conflict was the first step in a war between Rome and Palmyra.

Odenatus’ Roman titles, such as chieftain (dux Romanorum) or viceroy of the entire east, differed from eastern dignities because they were not hereditary. Vaballat was therefore entitled to his father’s royal title, but not to his Roman offices. Although the Roman emperor recognized his authority over Palmyra, he denied him Roman dignities, which caused antagonism. Emperor Galien also had to intervene to seize central power over the east. The History of Augustus mentions that the emperor sent the praetorian prefect, Aurelius Heraclianus, to regain imperial power over the east, but was repulsed by the Palmyra army. This is doubtful, however, as Heraclianus was involved in the assassination of Emperor Galien in 268 CE. Odenatus was murdered shortly before the emperor, so Heraclianus could not be sent east to fight Palmyra’s army and then return to the west and participate in the murder of Palmyra. emperor.

It is not known how large the territories Zenobia exercised in the early period of rule. Probably, however, she ruled the lands controlled by her deceased husband. The History of Augustus mentions that Zenobia took control of the east during the reign of Galien.

Ancient sources did not record that Zenobia encountered political opposition when she ascended the throne of Palmyra. The most serious rivals may have been the provincial Roman governors, but no records mention Zenobia waging a war with him. Neither of them tried to remove her from the throne either. Apparently, they all supported Waballat as Odenatus’ successor. Zenobia devoted her first years of rule to securing the borders with Pressure, by fortifying many border towns and settlements and pacifying Arab tribes. There is some evidence that Palmyra must have won a victory over the Persians, such as that Waballat assumed the title of “Great Persian Conqueror”, which meant that there must have been some unwritten war in which Palmyra was victorious.

Expansion and first conflicts with Rome

In 269, when Claudius Gothicus (Galien’s successor) defended the borders of Italy and the Balkans against German invasions, Zenobia strengthened its position. Roman officials in the east faced a difficult choice, as they had to choose between loyalty to the emperor and the growing demands of Zenobia, who demanded more and more loyalty from them. It is not clear when and why Zenobia decided to use the armed forces to strengthen her power in the east. Probably this was to maintain the dominance of Palmyra, against the opposition of Roman officials. It cannot be ruled out that Zenobia noticed the weakness of the Roman central authority and the related inability to defend the provinces, and understood that the only way to maintain stability in the East was direct control over the region. She probably also wanted to protect the economic interests of Palmyra, as merchants from Egypt and Bostra were her economic rivals.

In the summer of 270, as Claudius struggled with the Goths in the Thracian mountains, Zenobia sent her army, led by General Zabdas, to Bostra, the capital of the Arabia Petraea province. The Roman governor of the province, Trassus, confronted the invaders at the head of the 3rd Cyrenaica Legion, but was defeated and killed. Zabdas soldiers ransacked the city and destroyed the Temple of Zeus Amun, which was the sanctuary of the 3rd Legion. Following the victory, Zabdas marched south along the Jordan Valley and met little resistance. There is also evidence that Petra was attacked at the same time by small forces that infiltrated the province. Arab and Judean forces were finally defeated. Palmyra’s dominance in Arabia is confirmed by numerous milestones, signing with the name Waballata. The conquest of Syria did not require much effort, as Zenobia was highly respected there, especially in Antioch, which was considered the capital of Syria. The invasion of Arabia coincided with the cessation of money issuing on behalf of Claudius by the mints of Antioch, which meant that Zenobia had increasing power in Syria. From November 270, the mints of Antioch minted coins in the name of Vaballat.

The Arab milestones portrayed King Palmyra as the Roman governor and emperor, as Zenobia probably wanted to show that he was acting as the emperor’s representative and securing the eastern provinces on his behalf, while he fought in Europe. While Waballat’s use of these titles could mean that he was claiming the imperial throne, Zenobia could still pretend to be the emperor’s subject, for the title of emperor meant not so much the imperial ruler as the commander in command of the army.

Palmyra’s invasion of Egypt is explained by the fact that Zenobia wanted to secure an alternative trade route to the Euphrates, which had been cut because of the war with Persia. On the other hand, the merchants had only a partially blocked route, and the attack on Egypt could have been the result of Zenobia’s own ambitions. The date of the invasion is unknown. The Roman historian Zosimos claimed that it took place after the Battle of Niš but before Claudius’ death in the summer of 270 CE. Other sources say the attack came after the Emperor’s death, which spurred Zenobia to invade. The arrival of the Palmyra army on the Egyptian border caused unrest in the provinces, as Zenobia had as many supporters as opponents among the Egyptians.

The situation of the Romans was made worse by the fact that the prefect of Egypt, Tenagino Probus, was busy fighting pirates and was outside the province. According to Zosimos, the Egyptian General Timagenes helped the Palmyra army. Zabdas entered Egypt at the head of an army of 70,000 and defeated Roman forces. After the victory, the Palmyrians withdrew, leaving a garrison of five thousand. In early November, Tenagino Probus returned to the province and gathered an army. He drove the Palmyra forces out of Egypt and recaptured Alexandria, prompting Zabdas to return. The Palmyran general moved to Alexandria, which he regained, mainly with the help of local forces. The Roman Prefect withdrew south to Egyptian Babylon (now the city of Cherau). The final battle took place there. The Romans initially had the upper hand, but Timagenes knew the terrain better and launched an attack on the rear of the Romans, dealing them with defeat. Defeated Tenagino Probus, like Varus after the defeat in the Teutoburg Forest, committed suicide by piercing his own sword, and Egypt became part of Palmyra.

During the fighting in Egypt, Rome became embroiled in another succession crisis between Claudius’ brother Quintillus and General Aurelian. Egyptian papyri and coins, on the other hand, confirm the authority of Palmyra. Documents stop writing about imperial power between September and November 270, due to the prevailing succession crisis. From December, however, the dating of documents was resumed according to the years of the reign of the present Emperor and Zenobia’s son, Vaballat. Egyptian coins were also minted in the name of Emperor Aurelian and King Palmyra. However, there is no evidence that Zenobia ever visited Egypt.

In 271, Palmyra’s troops invaded Asia Minor. They took Galatia and came as far as Ancyra. Despite this, the mints of Bithynia and Kyzikos remained outside Zenobia’s control, and her attempts to subjugate Chalcedony for herself failed. The fighting in Asia Minor is poorly documented, but the western part of the region has not been subjugated to the queen. Despite this, the Palmyra Empire was at the height of its power.

Governance and Queen’s tolerance

Zenobia ruled a state made up of various nations. As an inhabitant of Palmyra, she was used to multiculturalism and multilingualism, as her city was a melting pot of nations. The queen state was culturally divided into an East Semitic part and a Hellenistic part. Zenobia tried to reconcile them with herself and apparently managed to get along with ethnic, local and religious groups. Zenobia tried to create her image as a Syrian monarch, a Hellenistic queen, and a Roman Augusta to gain broad support for her cause. Zenobia turned her court into a centre of science, and during her reign, there were many sophists and scholars in Palmyra. The most famous of them was Cassius Longinus, who came to Palmyra during the reign of Odenatus and became Zenobia’s teacher. Many historians accuse Longinus of encouraging Zenobia to conflict with Rome, although he probably did not have that much influence over the queen. Zenobia also commissioned several restoration works in Egypt, including the renovation of one of Memnon’s colossi.

The people of Palmyra were followers of polytheism, but Zenobia was very tolerant of Christians and Jews, and ancient sources wrote various things about the queen’s confession. Manichaeist records claimed that Zenobia followed their religion. More likely, however, the queen was tolerant of all religions that were marginalized by Rome because she wanted to win them over to her side.

Bishop Athanasius the Great wrote that Zenobia did not give the Jews back any of the churches so that they could turn them into synagogues. Although the queen was not a Christian, she understood how many followers Christianity was winning and how much influence the bishops had among their faithful. In other cities of the near flight, too, Christians were under the protection of the queen and were able to profess their religion without fear.

About a hundred years after Zenobia’s rule, Athanasius the Great, wrote in his History of the Arians that the queen was Jewish. Several later historians have given similar information, although there is no hard historical evidence to back it up.

Zenobia probably spent most of her life in Antioch, which was the administrative capital of Syria. Before the institution of monarchy, Palmyra had the status of a Greek polis, and the senate was responsible for most of the civil affairs. Odenatus allowed him to continue, as did Zenobia, but the Queen apparently ruled in an autocratic manner. Septimius Vorod, the viceroy of Odenatus and one of the most important officials, disappeared from the records after Zenobia’s accession to the throne. The queen also gladly allowed the eastern nobility to power. Its most important courtiers and advisers were its generals, Septimius Zabdas and Septimius Zabbai. Both commanders served Odenatus faithfully and received the name Septimius in recognition.

Odenatus respected the Roman emperor’s privilege to appoint provincial governors, and Zenobia continued this policy in the early days of his rule. Although the queen did not interfere with the current administration, she probably had the right to command the governors when it came to defending the borders. During her rebellion, Zenobia kept the Roman forms of administration but appointed governors herself.

Settlement with Rome

Initially, Zenobia avoided provoking Rome, demanding for herself and her son the titles inherited from Odenatus, a subject of Rome and defender of the eastern borders of the empire. After the territorial expansion, she wanted to be recognized as the empire’s partner in its eastern part and introduced her son as the emperor’s subordinate. In late 270, Zenobia had coins minted with images of Aurelian, who was called emperor, and Waballat, with the title of king.

The emperor’s acceptance of Palmyra’s power in Egypt is debatable. At first, he recognized Zenobi’s rule of Egypt, but he probably did so solely because he was too busy fending off barbarian attacks on the western part of the empire. His approval of the queen’s actions may also have been a smokescreen to give the queen a false sense of security while the emperor rallied his army and prepared for war. Additionally, Aurelian probably did not want to get rid of the grain supplies for Rome, which Zenobia continued to ship.

Rebellion against the emperor and fall

The Palmyrian inscription, dated August 271, describes Zenobia in Greek as “eusebes” or “pious”. This title, often assumed by Roman empresses, is considered her first step to becoming imperial. Another Greek inscription calls her “sebaste” so meaning “wonderful”, “divine” (Latin for augusta). In late 271, Egyptian grain receipts equated Aurelian and Waballat, calling them both emperors. Eventually, Palmyra severed all ties with Rome, and the mints of Alexandria and Antioch ceased minting coins with the image of Aurelian in April 272, replacing him with the image of Zenobia. Both the mother and her son were titled, emperor and empress.

Zenobia’s adoption of the imperial title meant usurpation of power, the declaration of Palmyra’s independence, and an open rebellion against Aurelian. It is not known why Zenobia proclaimed herself empress just then.

It was probably influenced by the fact that in the second half of 271, Aurelian gathered an army and began to march east, but was stopped by the Goths’ attack on the Balkans. Zenobia must have understood that Aurelian would not give up on regaining the lost lands and there was no point in pretending to be the emperor’s subject, as war is inevitable. Perhaps she also decided that accepting the imperial title would give her more authority and attract more soldiers and possible allies under her banners.

Aurelian entered Asia Minor most likely in April 272. The seizure of Galatia went smoothly. The Palmyra forces withdrew and the provincial capital, Ancyra, was seized without a fight. All the cities of Asia Minor surrendered to the Romans one by one, and only Tyana resisted before finally laying down her arms. These successes opened the way for Aurelian to attack Palmyra, which was the heart of Syria. At the same time, another Roman army struck Egypt in May 272. In early June, the Romans capture Alexandria, and over the next few weeks, they capture the rest of Egypt. Zenobia apparently withdrew most of its troops from Egypt, focusing on defending Syria, whose fall would mean the end of Palmyra.

In May 272, Aurelian marched to Antioch. About forty kilometers north of the city, in the Battle of Immae, he crashed the Palmyra army led by Zabdas. As a result, Zenobia, who was in Antioch, withdrew with her army to Emesa. Zabdas tried to hide the defeat from the inhabitants of Antioch and organized a fake triumphal procession through the streets of the city, in which the captured “captives” were led, including a grey-haired man pretending to be Aurelian. It did not do much, however, because the next day the Romans seized Antioch and then marched further south. Outside the city of Emessa, they encountered a Palmyra army, under the personal command of Zenobia and Zabdas. There was a battle. Despite the initial advantage, the Queen’s forces suffered a devastating defeat, losing almost most of their troops. The Greek historian Zosimos described the battle as follows:

The Palmyrenes therefore ran away with the utmost precipitation, and in their flight trod each other to pieces, as if the enemy did not make sufficient slaughter; the field was filled with dead men and horses, whilst the few that could escape took refuge in the city.

– Nova Historia, 1.53.3

Zenobia had to flee to her capital, and the Romans seized the city where they captured the queen’s treasury. Palmyra began to prepare for the siege. Aurelian blocked the city, cutting it off from its food supply. The story of Augustus reports that the emperor also made attempts to negotiate, trying to persuade Zenobia to surrender, but the queen refused, announcing that she was waiting for Persian reinforcements:

I might add thereto that such was the fear that this woman inspired in the peoples of the East and also the Egyptians that neither Arabs nor Saracens nor Armenians ever moved against her. Nor would I have spared her life, had I not known that she did a great service to the Roman state when she preserved the imperial power in the East for herself, or for her children. Therefore let those whom nothing pleases keep the venom of their own tongues to themselves. For if it is not meet to vanquish a woman and lead her in triumph, what are they saying of Gallienus, in contempt of whom she ruled the empire well?

– Historia Augusta, 30.7-10

Most likely, however, the queen was lying, because if she were in fact in an alliance with the Persians, the war would have been waged on a much larger scale, while the Persian army did not start any military operations. The Romans began a regular siege. The people of Palmyra were in a difficult situation. The city walls were not strong and the food supplies were insufficient, which effectively lowered the morale of the defenders. Zenobia, along with her sons and retinue, finally escaped from the besieged city. She intended to flee to Persia, hoping that its inhabitants would help her fight the Romans. However, her escape was unsuccessful and was captured by the Romans before she could cross the Persian border.

Captivity and further fate

When news of the queen’s capture reached Palmyra, the city immediately surrendered to the Romans. Aurelian had taken countless treasures from Palmyra, but he would not let his troops plunder the city. The emperor then sent Zenobia and her courtiers to Emesa, where they were to be tried for treason and rebellion against the empire. The History of Augustus reports that Zenobia blamed her advisers for encouraging her to rebel against Rome, including the philosopher Cassius Longinus. All indicated by the queen were executed, including General Zabdas. However, Zenobia and her sons were left alive

The further fate of Zenobia has not been known since then, as different sources give different versions of the events. Some say that Aurelian took the Queen and her sons to Rome to glorify his triumph, but did not survive the journey. Zenobia was to die of illness or starve to death. Her sons drowned in the sea while crossing the Bosphorus. Others, on the other hand, say that Zenobia survived the trip to Rome. She walked in Aurelian’s triumphal procession, chained, and then, in accordance with old Roman custom, was slain. However, the author of The History of Augustus described that Zenobia survived the journey to Rome and was led in Aurelian’s triumphal procession, adorned with jewels and precious stones, so large that she bent beneath them. She stopped often, complaining that she couldn’t bear the weight of all these ornaments. Her legs were chained with gold and her hands with silver chains. A gold chain was placed around her neck, which was shaken by a jester from Persia. It was a reminder that the queen had hoped in vain in the Persian army.

Usually, after a triumph, the Romans lost their captured leaders. Vaballat and the other sons of Zenobia no longer appear in any sources, so they must have been killed. The story of Augustus mentions that the emperor spared Zenobia’s life. In addition, he married her to a Roman noble and donated a villa in Tibur (now Tivoli), where the former queen of the desert lived as a Roman matron. Her daughters are said to have become the wives of distinguished senators. When the senators reminded Aurelian that he had triumphed over a woman, the emperor was to reply, “Yes, but what a woman she was!”

Rating

Zenobia was an enlightened ruler and favoured the development of science in her court, which was open to scholars and philosophers. She was tolerant of her subjects and protected religious minorities. The Queen maintained a stable administration that ruled over a multicultural and multi-ethnic empire. Her rise to power and fall were an inspiration for many historians, artists and writers, and to this day she is considered the national heroine of Syria.