- India

- International

A forgotten tale: how the first Nagamese book is seeking a reprint

Navamalati Chakraborty’s “Nagaland” was the first Nagamese book ever written, and subsequently forgotten. It might be brought back to life.

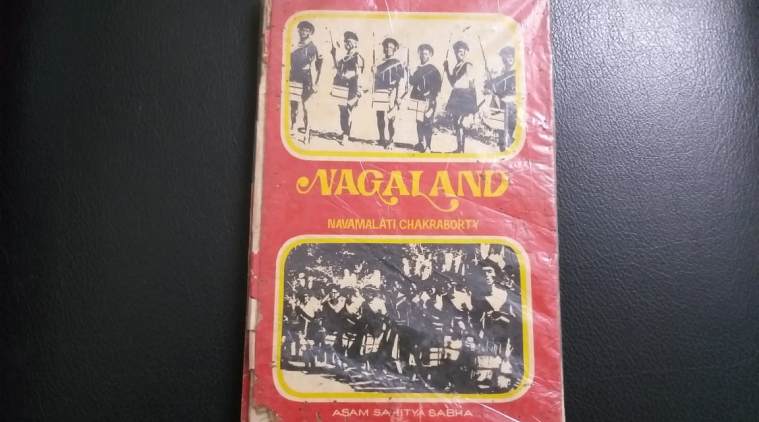

Navamalati Chakraborty’s Nagaland (1979) is the first book to be ever written in Nagamese. The book is now seeking a reprint. Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

Navamalati Chakraborty’s Nagaland (1979) is the first book to be ever written in Nagamese. The book is now seeking a reprint. Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

There aren’t many copies of Navamalati Chakraborty’s Nagaland, which was published in 1979, around today. The author, too, has just one crumbly, “worm-infested” copy in her possession.

“Back in 1979, book releases were nothing like the ones we have today,” says Chakraborty, 65, over the phone from Kolkata, where she now lives. “I wrote a book, it got published, it sold reasonably at the regional book fair — and we all went back to sleep!”

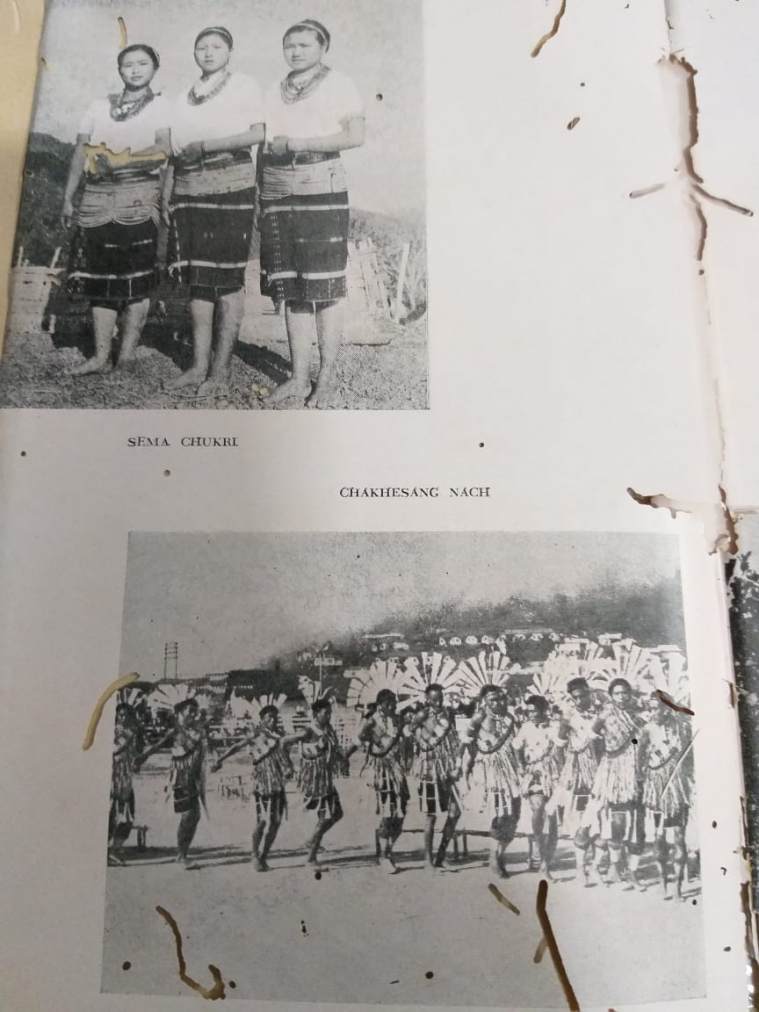

Today, very few own the book—a slim 122-page novel about the cultural history of the state published by the Asam Sahitya Sabha. Fewer know about it. While books about Naga culture and history are aplenty, Chakraborty’s book is significant because it was the first book to written in Nagamese. In fact, it’s one of the very few around.

This is because Nagamese — a ‘pidgin’ tongue comprising Assamese, Bengali, Hindi and English words — doesn’t have a script of its own, is rarely ever used in formal written communication, and lacks standardisation. In fact, for years Nagamese has been described as a language that developed for trade and business, a “bazaar” language. Yet, it remains the lingua franca of Nagaland, spoken across the state.

From two chapters to 14

Like all great ideas, Navamalati Chakraborty’s Nagaland too, started with a conversation. But the author—then a 22-year-old pursuing her Master’s degree in English — was never a part of it. “But I was listening in,” Chakraborty recalls, with a laugh.

In 1975, Chakraborty had just moved to Nagaland from Assam after her marriage, and her father would visit often. On one of her father’s visits, a few literary guests were over, and discussing an upcoming publication.

“I heard them speaking about a set of seven books the Asam Sahitya Sabha was publishing on the seven sister states of the Northeast,” says Chakraborty, “The author for the Nagaland book had, however, dropped out.”

In the days that followed, Chakraborty kept trying to convince her father that she was perfect for the job. “I had been living in Nagaland for a while. I loved the people. I loved their culture. My father brushed it aside in the beginning. Later, because my persistence, he asked me to write two chapters — like a test. He was a stern man,” she says.

Chakraborty’s father, Padma Shri Maheswar Neog was one of Assam’s foremost cultural scholars, and had served as the President of the Asam Sahitya Sabha in 1974.

Not many know about Chakraborty’s Nagaland. Today, the author has one crumbling, ‘worm-infested’ copy.

Not many know about Chakraborty’s Nagaland. Today, the author has one crumbling, ‘worm-infested’ copy.

Chakraborty set to work immediately, and planned out not two, but 14 chapters for the book. “My father was suitably impressed. He then suggested that I write the book in Nagamese, and not in English like I had planned,” she says.

For Chakraborty, whose mother tongue was Assamese, it was not that hard. “Being an Assamese, Nagamese came to me naturally. Back in 1974, anyone who visited our Kohima home, would speak only in Nagamese. That is how I picked it up,” she says.

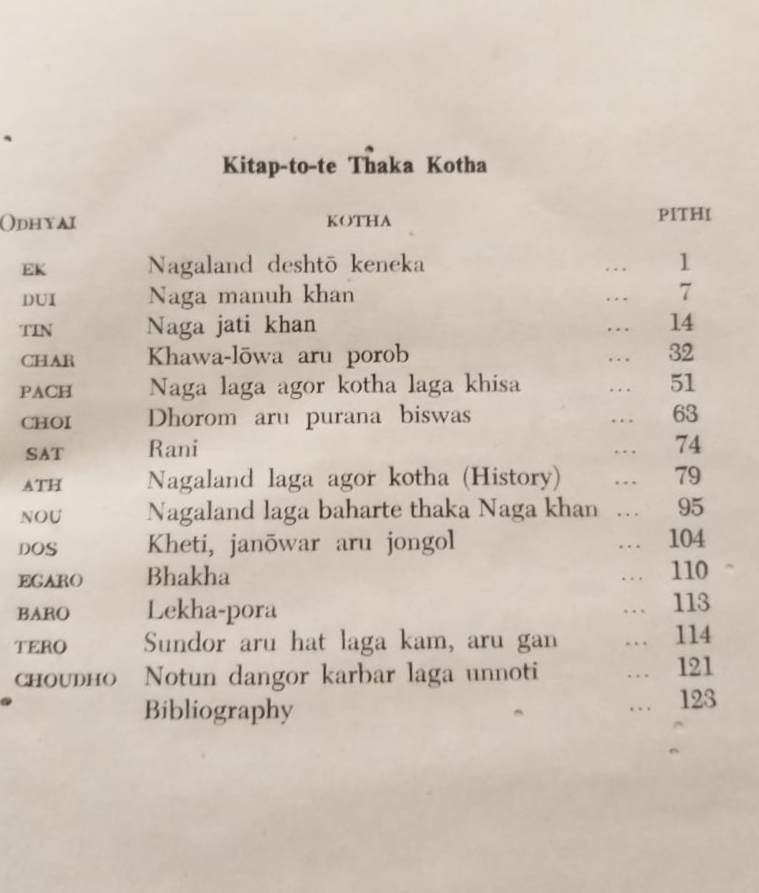

In May, 1979, a thousand copies of the book were printed, and 50 reached Chakraborty’s house in Kohima. Written in the Roman script, the book, as per Chakraborty’s original plan, comprised 14 chapters on various topics, including food (in a chapter called Khawa-lowa aru porob), history (in Nagaland laga agor kotha), and folk songs (in Sundor aru hat laga kam, aru gan).

“I never really tried to find out how the book did. But when a professor from Guwahati University visited me in Nagaland, he asked me for a copy because he was not able to buy one of his own,” says Chakraborty. Apparently, on day two of the 1979 Guwahati Book Fair, the book sold out. The book, which cost Rs 10, was never reprinted.

Her one and only book

Chakraborty moved to Calcutta in 1995—and while she never wrote a second book, she continued to promote Nagamese whenever she could. “At lectures in the Calcutta University, I would present papers on the language—I loved talking about the Naga people and loved them heartily,” she says.

While Chakraborty describes Nagamese as “an assortment of words—grammatically simplified, roughly hewn and beautifully woven together by the necessity of communication in the day-to-day life of the people”, the language has often been regarded as a threat to indigenous tribal tongues of Nagaland.

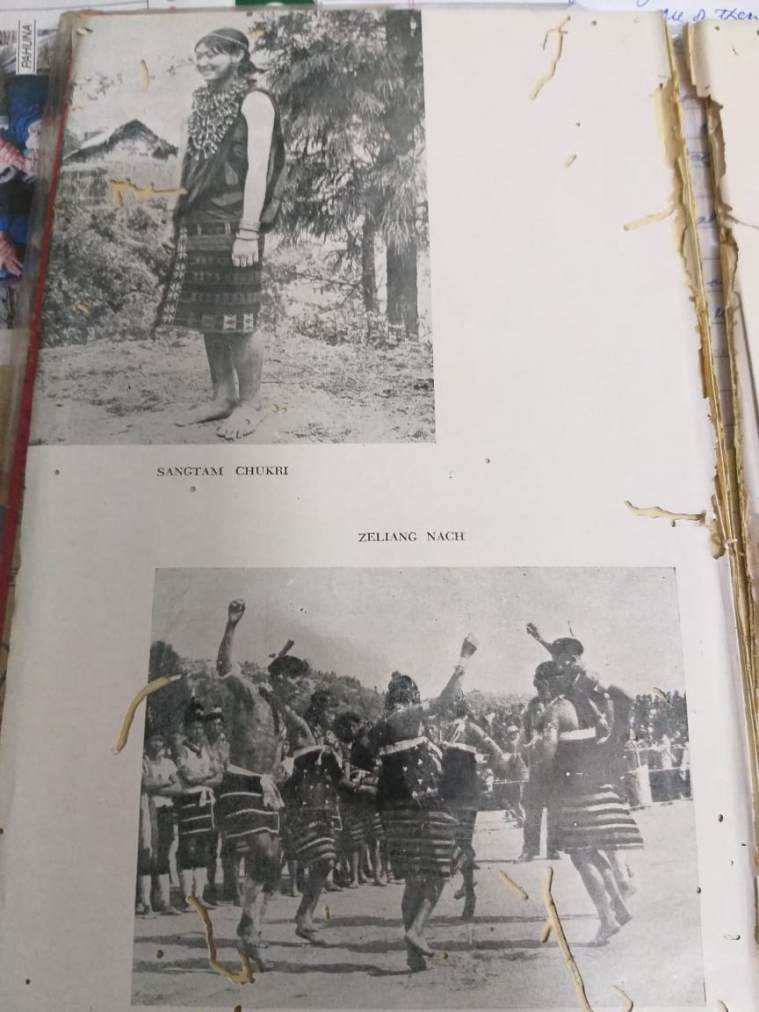

“Nagaland is made up of several tribes, each with its own language,” says Dr. D.Kuolie of of the Ura Academy, which works to preserve the state’s indigenous languages, Tenyidie in particular.

Navamalati Chakraborty at her residence in Kolkata. Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

Navamalati Chakraborty at her residence in Kolkata. Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

According to language data of Census 2011, the state has 14 languages and 17 dialects, making it one of the most diverse in the country. While English continues to be the state’s official language (since its creation in 1963), the tribal languages (such as angami, lotha, ao konyak etc) are limited to the specific tribes they are spoken in.

“In this context, Nagamese worked wonders as a means of communication both among the natives as well outsiders,” says Chakraborty.

Today, Nagamese is spoken, although in different forms, across the state — serving as the primary connector language. Over the years, it has been used in the legislative assembly, in radio broadcasts and church services. There are Nagamese films, songs and even, since 2013, a Nagamese language daily newspaper called Nagamese Khobor that was launched by a woman named H. Lemei Phom, and promoted as the “World’s First and Only Nagamese Newspaper”.

The Nagamese book — written in Roman script — has 14 chapters about the culture and history of Nagaland. Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

The Nagamese book — written in Roman script — has 14 chapters about the culture and history of Nagaland. Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

Yet, on paper, the language doesn’t have a standardised form. But over the years scholars and linguists have tried to study the language. The first reference to Nagamese can be found in J H Hutton’s The Angami Nagas (1921), where he refers to it as a “bastard tongue”. In 1969, Dharani Barua developed a Nagamese-into-Anglo-Hindi-Ao dictionary specifically for the army officials posted there. MV Sreedhar of the Central Institute of Indian languages tried to make sense of it in two publications: Naga Pidgin: A Sociolinguistic Study of Inter-lingual Communication Pattern (1974) and Standardized Grammar of Naga Pidgin (1985). In 1985, a grammar book in Nagamese, Nagamiz Kothalaga Niyom, by B K Boruah was published. Chakraborty’s Nagaland still holds the distinction of being the first.

Daughter wants to reprint book

Chakraborty’s family is now looking to reprint the book. Her daughter Navanita, a Dubai-based writer, says that the talks are on with publishers but “no one has committed for sure.”

This could probably be because of the political overtones Nagamese has acquired recently.

In 2015, the Central government proposed that Nagamese be given official recognition. The move was met with opposition from many quarters. The Naga Students’ Federation (NSF) said in a release: “We need more time to develop and promote a language which can be called as our own ‘Naga Language’ and not a market language which is a mixture of Hindi, Assamese, Bengali, English and many other dialects.”

According to Dr Kuolie, who has been a linguist for decades, a language cannot be viewed in isolation — “core factors to develop a language requires authentic data collection: be it social, political, cultural or religious.”

Chakraborty describes Nagamese as “an assortment of words—grammatically simplified, roughly hewn and beautifully woven together by the necessity of communication in the day-to-day life of the people.” Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

Chakraborty describes Nagamese as “an assortment of words—grammatically simplified, roughly hewn and beautifully woven together by the necessity of communication in the day-to-day life of the people.” Photo Courtesy: Navamalati Chakraborty

“But Nagamese does not have that sort of history simply because it is a mix of so many languages. That is probably why Nagamese was formally never promoted,” he says.

While there is no concrete evidence of how Nagamese originated, many trace it back to trade relations between the Naga hills people and the Ahom kingdom in the 13th century.

“The only way Nagamese can develop is if a group of people take it forward. Development of literature is not an activity one can promote by just investing money it it. There has to be passion and an inner force guiding it,” says Dr Kuolie.

May 01: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05