Dec 09, 2021

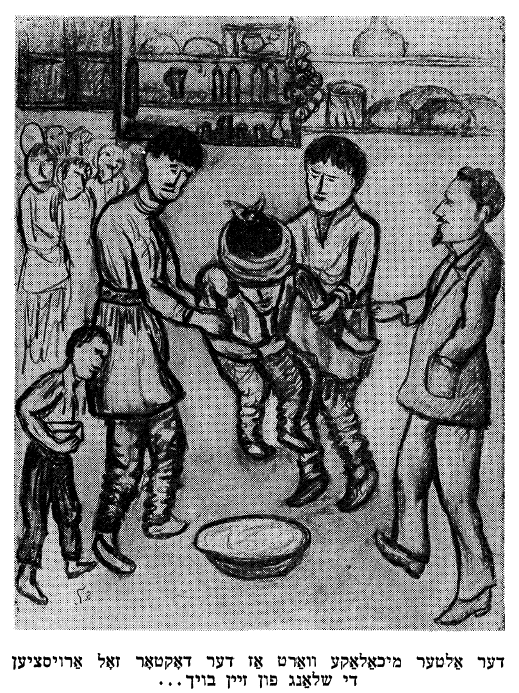

Illustration from Mayn Tatns Kretshme (New York: 1953). Source: Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library.

INTRODUCTION

Born in 1894, Yitzkhok Horowitz was a little-known Yiddish translator, editor, belletrist, and children’s playwright of Romanian extraction. After immigrating to the States in 1909, Horowitz published a slew of children’s plays throughout the ’20s, a decade which culminated with his most well-known work, a Yiddish translation of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, in 1929. He later became a writer for the Forverts. In 1953 he published his final work, the memoir Mayn Tatns Kretshme (My Father’s Tavern). Horowitz died in 1961 at the age of 67.

In My Father’s Tavern, as Horowitz explores his childhood in the eastern Romanian village of Popricani, it becomes impossible to discern where truth ends and where some sort of fable begins. Horowitz delivers not an objective account, but something perhaps even more immersive: an account from his own memory, detailing life not so much as it was, but as each character understood it to be. In his case, he splits his character, the narration weaving between the voices of his adult and child selves so as to speak to the dual aspects of each reader: the imaginative, starry-eyed child, and the sincere, sentimental adult, with a morsel of story for them both.

Among Horowitz’s more light-hearted musings, we meet the staple ghouls, ghosts, and goblins of Yiddish folklore that haunt the basement of the tavern. Other chapters feature tales of traveling Roma, the 1907 Peasants’ Revolt, and real life run-ins with forest wolves. But in the world of fantasy and superstition that was the village Popricani, a few stories emerge even more fantastic and superstitious than the rest. One such example is chapter eight, “The Snake,” wherein lies the tale of a most outlandish affliction, and of a man named Mihalache.

Click here to download a PDF of the text and translation. The full work is available at this link from the Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library.

דער אַלטער מיכאַלאַקע איז געװען אַ קלײן פּױערל, אַ ברעקל מענטש. אַז די קרעטשמע איז געװען געפּאַקט, האָט מען אים לחלוטין נישט אַרױסגעזען. מ'פֿלעגט נאָר הערן זײַן שפּיציק קול, װאָס האָט אַרױסגעקװיטשעט פֿון צװישן עולם װי דאָס פּישטשען פֿון אַ פֿײגעלע װאָס ליגט באַהאַלטן אין אַ טאָפּ.

און אָט דער קלײנינקער מיכאַלאַקע האָט געהאַט אַ געװאַלדיקן חשק אַרױסצוּװײַזן גבֿורה. דער חשק צו גבֿורה פֿלעגט אים מוטשען און טרײַבן צו די שװערסטע אַרבעטן. אַזױ, למשל, אַז מ'האָט באַדאַרפֿט אױסלאָדן אַ װאָגן מיט שװערע זעק, איז ער דער ערשטער צוגעשפּרונגען. די פּױערן, װאָס האָבן זיך מתעסק געװען מיט די זעק, האָבן געלאַכט, געהאַט שפּאַס מיט אים, און אים געטריבן פֿון װאָגן, װי מ'טרײַבט אַ קלײן פֿאַרעקשנט שײגעצל װאָס קריכט צװישן גרױסע. אָבער מיכאַלאַקע איז נישט אָפּגעטראָטן. ער איז געלאָפֿן אַרום דעם װאָגן, זיך געשטופּט מיט זײַנע שמאָלע פּלײצעס, געשטרעקט די קורצע הענטלעך, און זיך געריסן צו די זעק. שפּעטער, װען די פּױערן האָבן זיך אַפּאָרעט מיט דער אַרבעט און געװישט דעם שװײס, איז מיכאַלאַקע אױך געשטאַנען צװישן זײ און זיך אױך געװישט דאָס פּנים מיט אַ גרױסער פֿאַטשײלע.

און פּונקט אַזױ פֿלעגט דער אַלטער מיכאַלאַקע זיך רײַסן שלאָגן. דאָס חיות איז אים ממש אױסגעגאַנגען נאָך אַ געשלעג. אָבער קײנער האָט אים נישט געװאָלט צוליב טאָן. דער ביטול האָט אים שטאַרק פֿאַרדראָסן, און ער האָט געפּרוּווט כּלערלײ מיטלען אַרױסצורופֿן אַ געשלעג. אײן מיטל איז געװען׃ זײַן שטעקן. ער האָט פֿאַרלײגט דעם שטעקן אונטער דער פּאַכװע, מיטן שפּיץ אַרױסגעשטעקט, און זיך געשאַרט אַרום די בענק. זײַן שטעקן האָט יעדע װײַלע פֿאַרטשעפּעט אַן אַנדער פּױער, אָבער קײנער האָט זיך נישט געמאַכט װיסנדיק. האָט מיכאַלאַקע געפּרוּווט זײַן צװײט מיטל׃ דעם גאַרטל. ער האָט אױפֿגעװיקלט זײַן לאַנגן װאָלענעם גאַרטל און אים געלאָזט זיך נאָכשלעפּן אױף דער ערד. די פּױערן האָבן געװוּסט זײַן כּװנה, און אױסגעמיטן דעם גאַרטל. אַפֿילו די שיכּורע פּױערן האָבן זיך באַמיט צו באַהערשן זײערע לױזע, װאַקלדיקע פֿיס.

דער סוף איז געװען – װי אַלע מאָל. מיכאַלאַקע איז געבליבן שטײן אין מיטן קרעטשמע מיטן אױפֿגעװיקלטן גאַרטל – אַ פֿאַרשעמטער און געקרענקטער פֿון אַלעמענס ביטול.

*

Old Mihalache was a tiny peasant, a crumb of a man really. If the tavern was full, you couldn’t see him at all. But you could always hear his shrill little voice shrieking above the crowd, like the chirping of a bird hidden in a kettle. And this very same Mihalache had a remarkable need to prove his might. It was a need that tormented him and drove him to do the most backbreaking labor. For example, when there was a wagon full of heavy bags to unload, he was the first to hop to it. The peasants handling the bags mocked and ridiculed him, shooing him away from the wagon as one shoos away a stubborn young boy trying to mix among men. But Mihalache refused to step aside. He ran around the wagon, thrust his scrawny shoulders, strained his stubby arms, and seized hold of the bags. And you bet when the peasants finished the job and wiped the sweat from their brows, there was Mihalache standing among them, wiping his face with a big handkerchief.

And for the very same reason, old Mihalache was always looking for a fight — or better yet, spoiling for a fight. But nobody would give him the satisfaction. It was precisely their indifference that got under his skin, and when it did, he’d resort to all manner of provocation. One method involved his cane. He’d tuck it under his armpit with the crook poking out and shuffle around the tavern benches. Every so often his cane would snag one peasant or another, but they’d all pretend not to notice. So Mihalache would try his second method. He’d unfurl his long woolen belt and let it drag along the floor behind him. But the peasants knew what he was trying to do and they avoided the belt. Even the drunken peasants made an effort to steady their wobbling feet.

It would always end the same. Mihalache would wind up standing with his belt unraveled in the middle of the tavern, hurt and humiliated by everyone’s indifference.

*

פֿונדעסן האָבן אַלע ליב געהאַט מיכאַלאַקען. זײַן חשק צו גבֿורה און זײַנע טשיקאַװע שפּיצלעך האָבן פֿרײלעך געמאַכט אין קרעטשמע. דערפֿאַר, אַז ער פֿלעגט אַ זונטיק נישט קומען אין קרעטשמע, האָט ער אַלעמען אױסגעפֿעלט.

און אָט זענען שױן אַװעק עטלעכע זונטיקס זינט מיכאַלאַקע האָט זיך נישט געװיזן. דאָס איז נישט געװען זײַן טבֿע. די פּױערן האָבן זיך גענומען זאָרגן. בײַ װעמען זיך נאָכפֿרעגן איז נישט געװען, װײַל מיכאַלאַקע האָט נישט געהאַט קײן שכנים אָדער קרובֿים. ער איז געװען אַ פּאַסטעך בײַם פּריץ פֿון דאָרף און געװוינט אַלײן, אין אַ פֿאַרװאָרפֿענער כאַטע פֿון װאַלד, װײַט פֿון אַלעמען. ס'איז אָבער געקומען אַ זונטיק, װען די פּױערן אין קרעטשמע האָבן שױן נישט געקאָנט רוען. האָט מען געשיקט אַ שײגעצל אױסגעפֿינען װאָס מיט מיכאַלאַקען איז געשען.

דער שײגעץ האָט זיך אומגעקערט מיט אַ טרױעריקער בשׂורה׃

– מיכאַלאַקע איז קראַנק.

די בשׂורה האָט אַלעמען דערשלאָגן.

– ער ליגט? – האָט אַ פּױער געפֿרעגט.

– נײן, ער ליגט נישט, – האָט דער שײגעץ געזאָגט. – ער האַלט זיך בײַם בױך.

– ער קרעכצט?

– יאָ, ער קרעכצט.

די פּױערן האָבן געפֿרעגט דעם טאַטן װאָס צו טאָן. דער טאַטע האָט געהײסן ברענגען מיכאַלאַקען אין קרעטשמע. צװײ פּױערן זענען אַװעק אין װאַלד.

אין קרעטשמע איז די זונטיקדיקע שׂימחה שױן געװען אַ פֿאַרשטערטע. די קלעזמער האָבן שױן נישט געשפּילט, און די גלעזלעך זענען געשטאַנען לײדיק אױף די טישן.

דער טאַטע האָט אױפֿגעזוכט דאָס פֿלעשל מיט „דאַװילאַ־טראָפּנס“ און עס אַװעקגעשטעלט אױפֿן שענקטיש. די דאָרפֿישע פּױערן האָבן גוט געקאָנט דאָס קלײנע פֿלעשל מיט דער ברױנער פֿליסיקײט, װאָרן אַז עמעצער אין דאָרף האָט געהאַט בױכװײטיק, אָדער אַזױ געפֿילט שלעכט, איז ער געקומען צום טאַטן נאָך „דאַװילאַ־טראָפּנס“. די פּױערן האָבן שטאַרק געגלױבט אין דער רפֿואה.

אַ שײגעצל איז אַרײַנגעלאָפֿן און געזאָגט, אַז מ'ברענגט מיכאַלאַקען. אַלע זענען אַרױס אים באַגעגענען. די צװײ פּױערן האָבן געפֿירט מיכאַלאַקען בײַ די הענט. מיכאַלאַקע איז געװען בלײך און צעשראָקן. ער האָט אױסגעזען קלענער און דאַרער װי אַלע מאָל. מ'האָט אים אַרײַנגעפֿירט אין קרעטשמע און אַװעקגעזעצט אױף אַ באַנק לעבן שענקטיש. אײנער פֿון די צװײ פּױערן װאָס האָבן אים געבראַכט, איז צוגעגאַנגען צום טאַטן און אים עפּעס געזאָגט אין אױער.

מיכאַלאַקע האָט זיך צעשריגן׃

– ס'איז נישט קײן סוד! כ'האָב אײַנגעשלונגען אַ שלאַנג!

די פּױערן אין קרעטשמע זענען געבליבן שטײן מיט אָפֿענע מײַלער. דאָ און דאָרט האָט זיך אײנער איבערגעצלמט.

דער טאַטע איז צוגעגאַנגען צו מיכאַלאַקען מיטן פֿלעשל „דאַװילאַ־טראָפּנס“ אין האַנט.

– הער, מיכאַלאַקע, – האָט דער טאַטע צו אים געזאָגט. – דאָס קאָן נישט זײַן. אַ מענטש קאָן נישט אײַנשלינגען אַ שלאַנג.

מיכאַלאַקע האָט זיך נאָך העכער צעשריגן׃

– און איך האָב יאָ אײַנגעשלונגען!

– אָבער דאָס קאָן דאָך נישט זײַן, – האָט דער טאַטע אים געפּרוּווט דערקלערן. – מ'שלינגט נישט אײַן קײן שלאַנג.

מיכאַלאַקע איז װײכער געװאָרן, און געזאָגט כּמעט מיט געבעט׃

– אָבער איך האָב דאָך פֿאָרט אײַנגעשלונגען. – ער האָט געװיזן מיט דער האַנט אױפֿן בױך׃ – אָט דאָ ליגט זי. איך פֿיל װי זי װאַרפֿט זיך.

דער טאַטע האָט אַרױפֿגעגאָסן עטלעכע „דאַװילאַ־טראָפּנס“ אױף אַ שטיקל צוקער, און דערלאַנגט מיכאַלאַקען׃

– נעם, מיכאַלאַקע. דאָס װעט דיר העלפֿן.

מיכאַלאַקע האָט צעקײַעט דאָס שטיקל צוקער מיט די טראָפּנס און זיך פֿאַרקרימט װי פֿון אַ שטאַרקן געטראַנק.

אַ װײַלע שפּעטער איז דער טאַטע צוגעקומען און אים געפֿרעגט׃

– נו, װי פֿילסטו אַצינד?

מיכאַלאַקע האָט געפּינטלט מיט די אױגן׃

– דאַכט זיך, בעסער.

די פּױערן אין קרעטשמע זענען נשתּומם געװאָרן פֿון דער שנעלער רפֿואה. זײ זענען געװען זיכער, אַז די טראָפּנס האָבן פֿאַרסמט די שלאַנג, און אַז זי װעט אין גיכן אַרױסקומען אױפֿן זעלבן אופֿן װי אַלץ װאָס אַ מענטש שלינגט אײַן.

אַ בגילופֿינער פּױער האָט פֿון גרױס שׂימחה זיך צעטאַנצט אין מיטן קרעטשמע מיט אַ פֿלאַש אין האַנט. דערנאָך האָט ער זיך צוגעװאַקלט צו מיכאַלאַקען און אים געשטופּט די פֿלאַש צום מױל׃

– טרינק, מיכאַלאַקע! זאָל פּגרן די שלאַנג!

מיט אַ מאָל האָט דער בגלופֿינער פּױער זיך אַ װאָרף געטאָן אױף דער ערד, און גערעדט צו מיכאַלאַקעס בױך׃

– שלענגעלע, ביסט קאַפּוט! באַלד װעסטו פּגרן… יאָ, דו װעסט פּגרן, און מיכאַלאַקע װעט װערן געזונט.

די פּױערן אין קרעטשמע זענען צוגעשטאַנען, אַז מיכאַלאַקע זאָל דערצײלן װי אַזױ ער האָט אײַנגעשלונגען די שלאַנג. מיכאַלאַקע האָט זיך אָפּגעזאָגט.

– דערצײל, מיכאַלאַקע, – איז דער בגלופֿינער פּױער אױך צוגעשטאַנען, און אים װידער געשטופּט די פֿלאַש צום מױל. – טרינק, מיכאַלאַקע, און דערצײל.

װען מיכאַלאַקע האָט דערשמעקט דעם ריח פֿון בראָנפֿן, האָט ער אַ זופּ געטאָן פֿון דער פֿלאַש, אײן מאָל און אַ צװײטן מאָל, זיך אָפּגעװישט די װאָנצעס, און געזאָגט׃

– גוט, איך װעל דערצײלן. אָבער איך װיל איר זאָלט גלױבן װאָס איך דערצײל אײַך.

– אַוודאי וועלן מיר גלויבן, – האָט אַן עלטערער פּויער זיך אָפּגערופֿן.

– אַװדאי, אַװדאי, – האָבן אַנדערע אונטערגעכאַפּט.

אין קרעטשמע איז געװאָרן שטיל. די פּױערן האָבן אַרומגערינגלט מיכאַלאַקען און געװאַרט מיט שפּאַנונג. אַפֿילו דער טאַטע האָט זיך אָנגעשפּאַרט מיט די עלנבױגנס אין שענקטיש.

און מיכאַלאַקע האָט דערצײלט׃

– כ'בין אַרױס מיט די שאָף אין פֿעלד אַרײַן, װי אַלע מאָל. װען די שאָף האָבן זיך געפּאַשעט, האָב איך זיך אַװעקגעלײגט אױפֿן גראָז און, װי אַלע מאָל, געשפּילט אױף מײַן פֿײַפֿל. שפּילנדיק, האָב איך אײַנגעדרימלט, טאַקע מיטן פֿײַפֿל בײַם מױל. אין שלאָף האָט זיך מיר געחלומט, אַז איך בלאָנדזשע אין אַ מידבר. יאָ, אין אַ מידבר, װי איך בין אַ קריסט. די זון האָט געברענט, און מיך האָט שטאַרק געדורשט. אָבער קײן װאַסער איז נישט געװען. קײן לעק װאַסער, װי איך בין אַ קריסט. איך האָב שױן געפֿילט, אַז איך גײ אױס פֿון דורשט. נאָר מיט אַ מאָל האָט זיך באַװיזן אַ ריטשקעלע. אַזױ װי פֿון הימל, װי איך בין אַ קריסט. איך בין צוגעפֿאַלן צום ריטשקעלע און זיך גוט אָנגעטרונקען. דאָס װאַסער האָט מיך געקילט, אַ מחיה. אין מיטן טרינקען האָב איך זיך אױפֿגעכאַפּט און דערזען בײַ מיר אין מױל דעם עק פֿון אַ שלאַנג. יאָ, אַן אמתע שלאַנג, װי איך בין אַ קריסט. נאָר אײדער װאָס־װען, איז שױן די שלאַנג געװען אין מיר. איצט ליגט זי אָט דאָ בײַ מיר אין בױך. זי װאַרפֿט זיך און גריזשעט מיר די קישקעס.

די פּױערן האָבן אױסגעהערט מיכאַלאַקען און זיך איבערגעקוקט מיט שטױנונג און מיט שרעק. אַלע האָבן געגלױבט, אַז אַזױ װי מיכאַלאַקע האָט דערצײלט, אַזױ איז געשען. אַלע – אַחוץ דער טאַטע.

דער טאַטע האָט װידער דערלאַנגט מיכאַלאַקען אַ שטיקל צוקער מיט „דאַװילאַ־טראָפּנס“, און אים געהײסן אַהײמגײן זיך לײגן. די זעלבע צװײ פּױערן װאָס האָבן אים געבראַכט, האָבן אים צוריק אָפּגעפֿירט.

דער טאַטע האָט פֿאַרזיכערט די פּױערן, אַז די טראָפּנס װעלן העלפֿן.

אין קרעטשמע איז װידער פֿרײלעך געװאָרן.

*

Nevertheless, everyone loved Mihalache. His persistent posturing and curious antics pleased the tavern. On those Sundays when he didn’t come to the tavern, his absence was felt. Such was the case once, when it had been several Sundays since Mihalache had been seen around the tavern. This was not like him. The peasants had begun to worry. There was no one to ask after him because Mihalache had no neighbors or relatives. He tended the sheep of the village boyar and lived alone in a remote woodland hut, far from everyone. But there came a Sunday when the peasants could no longer stand idly by. They sent a boy to find out what had happened to Mihalache.

The boy returned with sad news: Mihalache was sick. The news hit everyone hard.

“He’s bedridden?” a peasant asked.

“No, not exactly; it’s his stomach.”

“Is he in pain?”

“Yeah, he’s in pain all right.”

The peasants asked my father what to do. My father told them to bring Mihalache to the tavern. And with that, two peasants went off to the forest.

In the tavern, Sunday’s celebration was just about spoiled. The musicians quit playing and the glasses stood empty on the tables.

My father found the bottle of “Davila drops,” and set it on the bar. Both the bottle and the brown tincture it contained were well known to the peasants, because whenever someone in the village had a stomach ache, or just plain felt unwell, they’d always come to my father for Davila drops. The peasants swore by the remedy.

A boy came running in and said they had returned with Mihalache. Everyone went out to greet him. The two peasants held him up by the arms. He was pale and frightened, looking smaller and scrawnier than ever. They led him into the tavern and set him down on a bench by the bar. One of the two peasants that brought him in approached my father and whispered something in his ear.

Mihalache shouted, “It’s no secret! I’ve swallowed a snake!”

The peasants of the tavern stood with their mouths agape. Some of them started crossing themselves. My father approached Mihalache with the bottle of Davila drops in hand.

“Listen here, Mihalache,” my father said to him. “That’s impossible. A man cannot swallow a snake.”

Mihalache shouted again, this time louder, “And yet I’ve swallowed one!”

“But that simply cannot be,” my father tried to explain. “One doesn’t just swallow a snake.”

Mihalache softened and said, almost pleadingly, “However, I have no less than swallowed one.” He motioned to his stomach, “It’s in there. I feel it squirming.”

My father poured a few Davila drops over a sugar cube and handed it to Mihalache. “Take it, Mihalache. It’ll help.”

Mihalache chewed the sugar cube and winced as if he’d taken a stiff drink. A little later my father came back over and asked him, “Well, how do you feel now?”

Mihalache blinked. “Better, I think.”

The peasants in the tavern were astonished by his swift recovery. They were certain the drops had poisoned the snake, and that it would soon come out the same as everything else a man swallows. A tipsy peasant danced gleefully around the middle of the tavern with a bottle of liquor in his hand. He staggered over to Mihalache and thrust the bottle to his mouth.

“Drink, Mihalache! It’ll kill the snake!”

Then the peasant dropped to his knees and spoke directly to Mihalache’s stomach. “Snakey, my boy, you’re done for! You’re gonna croak soon... Yes, you’ll croak, and Mihalache’ll get well again.”

The peasants in the tavern insisted that Mihalache tell them how he had swallowed the snake. Mihalache refused.

“Tell us, Mihalache.”

The tipsy peasant urged him too, and thrust the bottle to his mouth again. “Drink, Mihalache, then tell us.”

When Mihalache caught the scent of brandy, he took a swig from the bottle, once, then twice, wiped the dribble off his mustache, and said, “Very well, I’ll tell you. But you must promise to believe me.”

“Of course we’ll believe you,” an old peasant responded.

“Of course, of course,” the others chimed in.

The tavern went still. The peasants huddled around Mihalache and waited in anticipation. Even my father leaned in to hear, his elbows against the bar, as Mihalache began his story:

“Well, I was out in the field with the sheep, as usual. As the sheep were grazing I lay down in the grass and, as usual, I played my flute. As I played I drifted off, with the flute still between my lips. And while I slept I dreamt I was wandering the desert. You heard me right, the desert, swear to Christ. The sun was beating down and I was parched. But there was no water. Not a lick of water, swear to Christ. I knew I’d die of thirst. But all of a sudden I saw a brook, like a gift from the heavens… no, really — swear to Christ! I fell to the brook and began to slurp. The water cooled me down, it was quite the relief! But in the middle of slurping I awoke to find the tail end of a snake in my mouth. Yes, a real snake, swear to Christ. But it was too late, the snake was already inside. At this very moment it’s there in my belly. It’s tossing and turning and gnawing at my guts.”

The peasants listened closely to Mihalache and exchanged looks of fear and astonishment. Everyone believed that it happened just like Mihalache said it did. Everyone, that is, except my father.

My father handed Mihalache another sugar cube with Davila drops and told him to go home and lie down. The same peasants who brought him into the tavern brought him back home. My father assured the peasants that the drops would help, and the tavern was cheerful once more.

*

אױף מאָרגן איז מיכאַלאַקע געקומען אין קרעטשמע און זיך געקלאָגט, אַז בײַ נאַכט האָט די שלאַנג זיך װידער געװאָרפֿן.

דער טאַטע האָט אים נאָך אַ מאָל געגעבן טראָפּנס, און געפּרוּווט אײַנטענהן מיט אים׃

– מיכאַלאַקע, װאָס טוט זיך מיט דיר? װאָס האָסטו זיך אײַנגערעדט אַ שלאַנג אין בױך?

מיכאַלאַקע האָט געקײַעט דאָס שטיקל צוקער מיט די טראָפּנס, און גאָרנישט געזאָגט. ער האָט זיך געהאַלטן בײַם בױך, און געקוקט אױפֿן טאַטן מיט געבעט אין די אױגן. און אַזױ, מיט דער האַנט בײַם בױך, איז ער אַװעק אין װאַלד, צוריק צו זײַן כאַטע.

אַ פּאָר טעג האָט מען פֿון מיכאַלאַקען נישט געהערט. דער טאַטע איז געװען זיכער, אַז די טראָפּנס האָבן אים געהאָלפֿן. אָבער אָט איז געקומען אַ פּױער און געזאָגט, אַז מיכאַלאַקע האַלט שמאָל. ער דאַרט אײַן פֿון טאָג צו טאָג, און ער גײט אױס פֿון די כּוחות.

דער טאַטע האָט זיך מודה געװען, אַז ער װײסט נישט װאָס צו טאָן. ער האָט געהײסן װאַרטן ביז דער ראַיאָן־דאָקטער װעט קומען.

אָבער די פּױערן האָבן נישט געװאָלט װאַרטן. זײ זענען אַװעק אין אַ שכניש דאָרף און געבראַכט אַן אַלטע פּױערטע, װאָס האָט צוגעזאָגט צו הײלן מיכאַלאַקען. זי האָט אים געהײסן טרינקען בראָנפֿן, שטאַרקן בראָנפֿן, געמישט מיט פֿעפֿער. צו ערשט זאָל ער גוט צעקײַען דעם פֿעפֿער, און דערנאָך אים אַראָפּשװענקען מיט אַ מעסטל בראָנפֿן. אַזױ זאָל ער טאָן צען טעג נאָך אַנאַנד. פֿאַרן אַװעקגײן, האָט די פּױערטע אים װידער אָנגעזאָגט׃

– געדענק, מיכאַלאַקע׃ שטאַרקן בראָנפֿן! און פֿאַרגעס נישט דעם פֿעפֿער!

מיכאַלאַקע איז יעדן פֿאַרנאַכט געקומען אין קרעטשמע און אױסגעטרונקען אַ מעסטל בראָנפֿן מיט צעקײַעטן פֿעפֿער. אָבער אַז די צען טעג זענען אַװעק, האָט ער זיך נאָך אַלץ באַקלאָגט אױף דער שלאַנג. ער האָט פֿאַרלױרן דעם אַפּעטיט צום עסן, און איז געװאָרן דאַר װי אַ שטעקן.

אײן פֿאַרנאַכט האָט מיכאַלאַקע זיך קױם צוגעשלעפּט צו דער קרעטשמע. דער טאַטע האָט אים אָנגעגאָסן אַ מעסטל בראָנפֿן, װי אַלע מאָל, אָבער מיכאַלאַקע האָט זיך נישט צוגערירט צום בראָנפֿן. ער איז געזעסן אױף אַ באַנק, קעגן איבער דעם טאַטן, און געקרעכצט.

דער טאַטע האָט רחמנות געקראָגן אױף אים. ער איז צוגעגאַנגען און געזאָגט׃

– מיכאַלאַקע, אפֿשר נאָך טראָפּנס?

מיכאַלאַקע האָט געקוקט אױפֿן טאַטן מיט פֿאַרטרערטע אױגן׃

– אומזיסט… די שלאַנג װיל נישט פּגרן…

*

The next morning Mihalache came into the tavern and complained that the snake had been tossing and turning again. My father gave him the drops and tried to reason with him.

“Mihalache, what’s going on with you? How can you fool yourself into thinking such nonsense as a snake in your stomach?”

Mihalache chewed the sugar cube and said nothing. He held his stomach and looked at my father with pleading eyes. And just like that, with his hand at his stomach, he went off to the woods, back to his hut.

Nobody heard from Mihalache for a couple of days. My father was certain that the drops had helped. But then a peasant came and said that Mihalache was in critical condition. He was getting thinner each day and was growing weaker and weaker. My father had to admit he didn’t know what to do. He instructed them to wait until the district physician came.

But the peasants didn’t want to wait. They went off to a neighboring village and brought an old peasant woman who promised to heal Mihalache. She told him to drink brandy — strong brandy, mixed with pepper. He had to chew up the pepper first, and then wash it down with a shot of brandy. He was to do this for ten days straight. Before she left, the peasant woman warned him, “Remember Mihalache — strong brandy! And don’t forget the pepper!”

Mihalache came to the tavern every evening to chew pepper and drink a shot of brandy. But when the ten days came to an end, he hadn’t quit complaining about the snake in his stomach. He’d lost his appetite and was thin as a rail.

One evening Mihalache barely managed to drag himself to the tavern. My father poured him a shot of brandy as usual, but Mihalache didn’t touch it. He sat on a bench facing my father and moaned.

My father felt sorry for him. He went over and said, “Mihalache, some drops perhaps?”

Mihalache looked at my father with tears in his eyes and said, “No use... The snake won’t be killed...”

*

אַ פּאָר טעג שפּעטער האָבן עטלעכע פּריצים זיך אָפּגעשטעלט בײַ דער קרעטשמע. צװישן זײ איז געװען אַ מיליטערישער דאָקטער. דער טאַטע האָט אים דערצײלט פֿון מיכאַלאַקען און פֿון דער שלאַנג, װאָס מיכאַלאַקע מײנט אַז ער האָט אײַנגעשלונגען. די פּריצים האָבן זיך אָנגעלאַכט פֿון דער מעשׂה. פֿונדעסן זענען זײ צוגעשטאַנען צום דאָקטער, ער זאָל באַטראַכטן מיכאַלאַקען. דער דאָקטער האָט אײַנגעװיליקט, אָבער מיטן תּנאַי, מ'זאָל נישט לאַכן. ער האָט געזאָגט, אַז מיכאַלאַקע דאַרף גלױבן אַז ער האָט אײַנגעשלונגען אַ שלאַנג. נאָר אַזױ קאָן ער געהאָלפֿן װערן.

די פּריצים האָבן צוגערופֿן זײער קוטשער און אים געשיקט מיט אַ פּױער ברענגען מיכאַלאַקען. דערנאָך האָט דער דאָקטער אױסגעלײגט זײַן פּלאַן. ער האָט געהײסן דעם טאַטן אָנגרײטן אַ גרױסע שיסל מיט מילך, און אַרױסשיקן אַ ייִנגל אױפֿזוכן אַ שלענגל.

דאָס דאָרף האָט זיך באַלד דערװוּסט, אַז אין קרעטשמע געפֿינט זיך אַ דאָקטער, װאָס גײט הײלן מיכאַלאַקען. די פּױערן האָבן אַװעקגעװאָרפֿן די אַרבעטן און געלאָפֿן אין קרעטשמע. די װײַבער און קינדער זענען אױך נאָכגעלאָפֿן. די קרעטשמע איז געװאָרן איבערגעפּאַקט.

דער דאָקטער און די פּריצים זענען געזעסן אין אַ באַזונדער צימער. דאָרט האָט דער דאָקטער אײַנשטודירט מיטן טאַטן און מיט אַן עלטערן ברודער װאָס זײ דאַרפֿן טאָן. דער טאַטע האָט באַדאַרפֿט אַרײַנברענגען די שיסל מילך און זי אַװעקשטעלן אין מיטן קרעטשמע, און דער ברודער האָט באַדאַרפֿט האַלטן אָנגעגרײט דאָס שלענגל אין אַ קלײן קעסטל.

מיכאַלאַקע איז אָנגעקומען מיט דער פּריצישער דראָשקע. ער איז געזעסן הינטן, אױפֿן װײכן פּליושענעם זיץ, אַ דאַרער און אַ פֿאַרגעלטער. אין דער װײכער טיפֿעניש פֿון דער גרױסער פּריצישער דראָשקע האָט ער אױסגעזען װי אַ קלײן פֿיגורל, געקלעפּט פֿון חלבֿ. צװײ יונגע שקצים האָבן אים גענומען אױף די הענט און אים אַרײַנגעטראָגן אין קרעטשמע.

דער דאָקטער האָט אָנגעװיזן אױף אַ בענקל אין מיטן קרעטשמע. די פּױערן האָבן זיך גענומען רוקן און שטופּן צו די װענט. מיכאַלאַקע איז געזעסן אױפֿן בענקל לעבן דעם דאָקטער און געציטערט פֿון שרעק. אײן האַנט האָט ער געהאַלטן בײַם בױך, און מיט דער צװײטער האָט ער זיך געצלמט.

דער דאָקטער האָט אים געהײסן זיך באַרויִקן און דערצײלן, װי אַזױ ער האָט אײַנגעשלונגען די שלאַנג. מיכאַלאַקע האָט איבערדערצײלט די זעלבע געשיכטע, װאָס מיר האָבן שױן געהערט. דער דאָקטער האָט אַװעקגעלײגט אַ האַנט אױף זײַן אַקסל און אים געזאָגט, אַז אַזױנע זאַכן האָבן שױן געטראָפֿן, און אַז ערשט אַנומלט האָט ער אַרױסגעצױגן אַ שלאַנג פֿון אַ פּױערס בױך.

מיכאַלאַקע האָט זיך צעװײנט.

– װאָס װײנסטו? – האָט דער דאָקטער געפֿרעגט.

– כ'האָב מורא, – האָט מיכאַלאַקע געכליפּעט.

– האָסט נישט װאָס מורא צו האָבן.

– ס'עט װײ טאָן.

– ס'עט נישט װײ טאָן.

און כּדי אים נאָך מער צו באַרויִקן, האָט דער דאָקטער אים געזאָגט, אַז די רפֿואה באַשטײט פֿון מילך. אַ שלאַנג האָט ליב מילך, און אַז זי װעט דערשמעקן מילך, װעט זי אַלײן אַרױסקומען. מיכאַלאַקע דאַרף נאָר פֿאָלגן װאָס מ'װעט אים הײסן. ער דאַרף זיך לאָזן אױפֿהײבן מיט די פֿיס אַרױף און מיטן קאָפּ אַראָפּ, און כּדי דער קאָפּ זאָל זיך אים נישט פֿאַרדרײען, דאַרף ער זיך לאָזן פֿאַרבינדן די אױגן.

דער דאָקטער האָט צוגערופֿן צװײ הױכע פּױערן און זײ געהײסן זיך אַװעקשטעלן פֿון בײדע זײַטן. דעם טאַטן האָט ער געהײסן אַרײַנברענגען אַ שיסל מילך. דער ברודער איז שױן געשטאַנען לעבן דאָקטער מיטן קלײנעם קעסטעלע באַהאַלטן הינטער די פּלײצעס. דער דאָקטער האָט פֿאַרבונדן מיכאַלאַקעס אױגן מיט אַ גרױסער פֿאַטשײלע, און אַ װינק געטאָן צו די צװײ פּױערן. די פּױערן האָבן אַ כאַפּ געטאָן מיכאַלאַקען און באַלד איז ער שױן געהאַנגען אין זײערע הענט מיט די פֿיס אַרױף און מיטן קאָפּ אַראָפּ.

דער דאָקטער האָט אַרײַנגעשטעקט אַ פֿינגער אין מיכאַלאַקעס מױל, און באַפֿױלן׃

– ברעך, מיכאַלאַקע!

מיכאַלאַקע האָט זיך געװאָרגן מיטן דאָקטערס פֿינגער:

–איך קאָן נישט, דאָקטער.

– דו קאָנסט, מיכאַלאַקע, נאָר דו װילסט נישט.

– איך װיל, דאָקטער, נאָר איך קאָן נישט.

דער דאָקטער האָט טיפֿער אַרײַנגעשטעקט דעם פֿינגער׃

– ברעך, מיכאַלאַקע!

מיכאַלאַקע האָט געבראָכן.

– גוט אַזױ, מיכאַלאַקע! – האָט דער דאָקטער געזאָגט. – איצט נאָך אַ מאָל.

– מער קאָן איך נישט, דאָקטער. כ'לעבן.

דער דאָקטער האָט אַרײַנגעשטעקט צװײ פֿינגער אין מיכאַלאַקעס מױל׃

– דו קאָנסט! דו מוזסט! ברעך מיכאַלאַקע!

מיכאַלאַקע האָט װידער געבראָכן.

– בראַװאָ, מיכאַלאַקע! – האָט דער דאָקטער אױסגערופֿן און בגנבֿה אַרײַנגעלאָזט דאָס שלענגל אין דער שיסל מילך. – ביסט געראַטעװעט, מיכאַלאַקע! אָט איז די שלאַנג!

די צװײ פּױערן האָבן אַװעקגעשטעלט מיכאַלאַקען אױף די פֿיס, און דער דאָקטער האָט אים אױפֿגעבונדן די אױגן. װען מיכאַלאַקע האָט דערזען דאָס שלענגל אין דער שיסל מילך, איז ער אַװעקגעפֿאַלן אױף די קני און געקושט דעם דאָקטערס האַנט.

די פּױערן פֿון קרעטשמע האָבן זיך געצלמט.

*

פֿון יענעם טאָג אָן האָט מיכאַלאַקע זיך גענומען בעסערן. אין אַ שטיקל צײַט אַרום איז ער געװען דער זעלבער מיכאַלאַקע װאָס אַלע מאָל. ער פֿלעגט װידער קומען אין קרעטשמע, און װידער אַרױסװײַזן זײַן גבֿורה.

A few days later, several boyars stopped by the tavern. Among them was a military doctor. My father told him about Mihalache and the snake he thought he’d swallowed. The boyars had a good laugh at the story. Nevertheless, they insisted the doctor see Mihalache. The doctor obliged, but with the stipulation that they mustn’t laugh. He said that Mihalache had to believe he had truly swallowed a snake; only then could he be helped.

The boyar called over their coachman and sent him along with a peasant to bring Mihalache. Then the doctor laid out his plan. He instructed my father to prepare a large bowl of milk and sent a young boy to find a snake.

Soon the peasants in the village got word that there was a doctor in the tavern who was going to heal Mihalache. They dropped what they were doing and rushed over to the tavern. The women and children came too. The tavern was packed.

The doctor and the boyars sat in a separate room. There, the doctor along with my father and one of my older brothers carefully planned what they were going to do. My father was to bring in the bowl of milk and set it in the middle of the tavern, and my brother was to ready the snake in a small box.

Mihalache arrived in the boyar’s droshky. At once gaunt and a sickly shade of yellow, he sat in the back on a soft plush seat. In the pillowy confines of the boyar’s droshky he resembled a tallow figurine. Two young peasants took him by the arms and led him inside.

The doctor motioned to a bench in the middle of the tavern. The peasants began to move and push to the walls in order to clear a path. Mihalache sat on the bench next to the doctor, trembling with fear. He held one hand at his belly and crossed himself with the other. The doctor asked him first to calm down, and then to tell him how it was that he had come to swallow the snake. Mihalache told the same story we heard before. The doctor placed a hand on Mihalache’s shoulder and said that such things were known to happen, and that just the other day he had to get a snake out of a peasant’s stomach.

Mihalache started to cry.

“Why are you crying?” the doctor asked.

“I’m afraid,” Mihalache sobbed.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

“It’ll hurt.”

“It won’t hurt.”

And in order to console him further, the doctor told him that the remedy was nothing more than milk. Snakes loved milk, he said, and if the snake smelled milk it would come out of its own accord. Mihalache only had to follow his instructions. He had to be lifted with his feet in the air and his head toward the ground, and so that he wouldn’t get nauseous, he’d be blindfolded.

The doctor called over two tall peasants and had them stand at either side. He had my father bring out the bowl of milk. My brother stood next to the doctor with the tiny box concealed behind his back. The doctor blindfolded Mihalache’s eyes with a large kerchief and winked at the two peasants. The peasants grabbed Mihalache and soon he was hanging, just as the doctor said, with his feet in the air and his head toward the ground. The doctor shoved his finger down Mihalache’s throat and commanded, “Retch, Mihalache!”

Mihalache gagged on the doctor’s finger.

“I can’t, Doctor.”

“You can, Mihalache, you just don’t want to.”

“I want to, Doctor, I just can’t.”

The doctor reached further down Mihalache’s throat.

“Retch, Mihalache!”

Mihalache vomited.

“Well done, Mihalache,” the doctor exclaimed. “Now again.”

“I can’t anymore, Doctor. Really.”

The doctor stuck two fingers down Mihalache’s throat.

“You can! You must! Retch, Mihalache!”

Mihalache puked once more.

“Bravo Mihalache!” the doctor shouted, and slyly released the snake into the bowl of milk.

“You’ve been saved, Mihalache! Here’s the snake!”

The two peasants flipped Mihalache back onto his feet and the doctor untied the blindfold. When Mihalache saw the snake in the bowl, he fell to his knees and kissed the doctor’s hand.

All the peasants in the tavern crossed themselves.

*

From that day on Mihalache began to get better. After a while he was the same Mihalache he’d always been. He started coming back to the tavern to prove his might, just like he did before.