The Spanish artist, Dora García (*1965, Valladolid), employs for one of her core artistic strategies the disruption of the real and of the conventions that determine both the traditional exhibition of art and some of our everyday behaviours. By questioning the public’s expectations, she re-examines the parameters that define the nature of the artistic experience. Consisted mainly of performances, installations, talks, texts and photographs, her work creates a state of indeterminacy that blurs all boundaries between author and actor, reality and fiction and art and life.

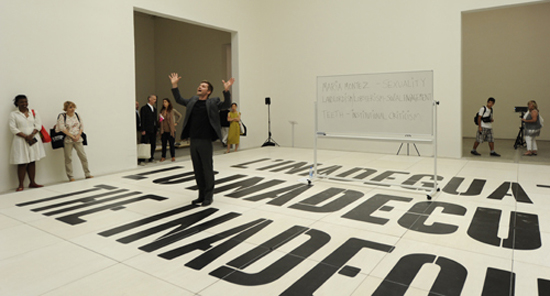

Invited by the Spanish Pavilion of the 54th Venice Biennale, Dora García created The Inadequate, which, in her own words, can be seen as “an extended performance”. An investigation around the notion of inadequacy, the work was conceived as a collaborative project that evolves in time. Spreading over a period of six months, the project consists partly of an installation including films and objects from the artist’s previous works; and partly of scheduled conversations on the notion of marginality with participants coming from all sorts of disciplines and of performances drawn

from the artist’s repertory (The Artist Without Works, Real Artists Don’t Have Teeth, etc.). The evolving nature of the work aims at denying the possibility of viewing the piece in its entirety, hence challenging the traditional experience and expectations of an exhibition visitor.

In the interview (conducted in Paris on 27th September 2011), we took The Inadequate as the starting point to discuss some of the key notions of Dora García’s work, such as the relationship between actor and author, fiction, representation and reality, as well as the position of the artist. For her, art is about the gesture of an artist and the figure of the author is epitomized by the image of a James Joyce “leaning against the wall”: “someone who watches the others busying themselves and is by nature outside of them.” A marginal. An inadequate?

Sandrine Meats

(Art Historian)

Paris, Nov 2011

DG – Dora García

SM – Sandrine Meats for InitiArt Magazine

Being inadequate

SM: The title of your work at the Venice Biennale 2011, The Inadequate, seems to be an undertone of an artist’s rejection of the idea of representing a country. What is exactly your position?

DG: The relation between the title and my malaise of representing a country has to be nuanced, and there has been some misunderstanding in the press so far, because it is not the main idea behind the title. The Inadequate comes from a longer research on the negotiation between author and audience, between actor and public and so, between the one who speaks and the one who listens, which is the core of my work. The idea of The Inadequate can be traced back in the work I did for Skulptur Projekt Münster in 2007, The Beggar’s Opera. In this piece, I tried to contradict expectations. This is something I have always been working with. There are very strong conventions in the way art is shown, perceived and commented upon. Amazingly enough, these conventions are incredibly strong and they weight as much on artists as they do on the public. So, in the Münster Skulptur Projekt, I tried to examine exactly how these expectations or conventions modify the meaning of the work by creating a work that was exactly the contrary to what one would expect in a sculpture exhibition in a public space. I believe this idea of “inadequate” has much more to do with that than with the idea of representing. Because, I have to clarify the misunderstanding and put out that I never got a commission to represent Spain, what I got is a commission to present my work in the Spanish Pavilion. They are very different things. If some people understand the commission as representing Spain, I’m very sorry because that’s something I cannot do.

Real Artists Don’t Have Teeth, performed by Jakob Tamm, in The Inadequate, Spanish Pavilion, 54th Venice Biennale, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Michel Rein.

SM: How did your investigation on the notion of inadequacy evolve from The Beggar’s Opera to the Venice Biennale piece?

DG: Starting from the Münster Skulptur Projekt, there has been an evolution into anti-psychiatry and a questioning about who determines us from being apt or inapt for society: who, in a sociological point of view, establishes the rules. Outsider art has also been a big inspiration for the project because, basically, outsider is something which is determined by others. In sociological terms, it is the others who determine that you are an outsider.

SM: So, your intention was to create a work which was inadequate to the Biennale?

DG: I have to say that it was almost unavoidable! I really believe that the worst place in the planet to see art is the Venice Biennale, in the sense that you have to see everything in one day, you are forced to consume. You have a limited amount of time and the way art is presented and mediated is almost inexistent. So, for me, it really is an anti-art place, in the sense that there is much more art anywhere else in Venice than in the Biennale. This does not mean that there is less life in one or the other, life is the same in both places. I think that the way it is made [in the Biennale] is against everything I believe should be made to the enjoyment and understanding of art. However said, I don’t think that understanding is the basic thing you have to do with art. What I mean is to understand the intention of the artist.

So, it was unavoidable to do something that would go against the regular conventions of the Venice Biennale. At the same time, I did not have to invent something specific because the work I do is by nature against that. It is a work that requires time, that develops in time, that no one can perceive in its totality. This is not specific to The Inadequate but typical of my work in general. So it is a way of working that goes against the idea that you have one ticket and four hours to see an enormous amount of artworks.

SM: This also undermines the idea of the institution as authority…

DG: I believe that we are all part of the institution. It is not something that you can say “I am outside” or “I am inside”. Of course, I am part of the institution of art. Even a first degree student in the art school is already part of the institution; the public is part of the institution. So, it’s a very complex thing, almost a kind of system or mood. It isn’t really linked to a physical reality, like a job, but it’s more a way of perceiving things. It’s very hard to declare yourself anti-institutional when you know you are inside the institution yourself.

There is a wider sense of institution that applies for instance in sociological studies and anti-psychiatry studies, which defines the institution as that which does not change. It’s that which is by nature established. It has certain rules so it will stay like that. For institutions, revolutions were made, to create new institutions. This process is something natural. It is something that has always been happening in art. If you change, it is for another institution.

SM: Can you talk about the process of working with state structures for The Inadequate?

DG: It has something very particular to it. There are two worlds, two ways of working which are completely alien. I have never done anything so difficult in my life in the sense that although there is good will and the funding comes from the state, the understanding of what contemporary art is, of what an exhibition is, is non existent. So it was very difficult to work with them, simply because we did not speak the same language. They are used to presenting art that is indeed very institutional in the sense that it stays the same, they don’t need to maintain, they don’t need to update, they don’t need to mediate. Also, the criticism and the feedback that you get, you feel that it is far more addressed to the state than yourself. So in that sense, it was hard and not always pleasant.

SM: Has there been any limitations?

DG: Only financial ones. There was no intervention at all.

Language: experiencing a cultural event

SM: An important aspect of The Inadequate is the numerous conversations taking place between invited participants, on the stage at the centre of the pavilion, throughout the whole duration of the work. These conversations are carried in different languages, though many are in Italian.

DG: Many are in Italian; some are in English, German and French. French is a common language I have with many Italians because many people who, in the 1970s and 1980s, shared revolutionary ideas and had to escape Italy came to Paris. But since we are in Italy, most of the conversations are in Italian.

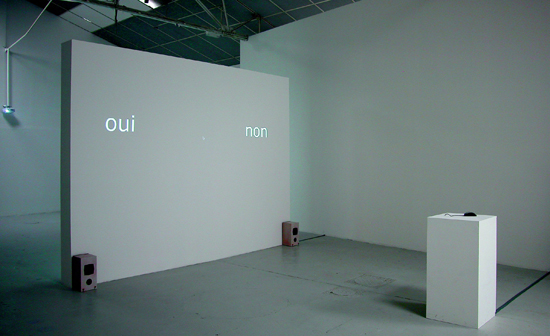

SM: Why did you choose to have the conversations happening in languages that visitors may not understand? Is it related to an investigation on the notion of communication as in some previous works?

DG: The Messenger (Brussels, 2002), for instance, which also takes place in the pavilion, is such a piece. The performance is about someone who learns by heart a sentence in a language unknown to him or her and tries to find someone who can understand that sentence. It comes from a very strong awareness that has to do with immigration, with multiculturalism. In the city, there are many things you don’t understand: foreign languages, letterings that are made for certain communities. And you don’t understand even if you speak the language of the place where you are. You can find something outrageous about it, but you can also find positive to see that there are streams of meaning that are coming just next to you and you have to do something to understand them. It is not that it is impossible to understand it, but you have to work for it. In the Biennale, like everywhere else in the art world, everything is in English because it is assumed that everybody understands it, but this is also not true. I think it is important to underline, and this is a reaction against mass art conception, that if you want to understand certain cultural things, you must make an effort to understand them. I can’t say I speak Italian myself. This means that we had to make an effort to understand each other. So, there is a kind of negotiation to find a common ground. This is an ideological position which I am convinced of, but it is also a very practical choice: many of those people, whom I really wanted to meet, did not speak anything else. So I decided to keep this system, which is very common to everyone who has lived outside of their country, to have several languages running at the same time and to learn to deal with that. You don’t get 100%, but you get something. And I think that even if you don’t understand, it has a certain quality. When you witness a cultural event, for instance, if you go to Japan or any exotic place, you certainly won’t feel the same as the Japanese are feeling, but you feel something. And no one can take that away from you. So, if I listen to an Italian conversation, I won’t get the same as an Italian but I still get something.

Occupation instead of exhibition

SM: Can you comment on the idea of occupation as opposed to that of exhibition, which in a way is a description of The Inadequate?

DG: Here we have to come back to what I have said about people focusing on the idea of me feeling inadequate to represent Spain, which is true, but no more than anyone else. Any artist is inadequate to represent a country, especially because no one knows what a country is anymore. I think that I have more in common with a certain spectrum of the population which has a similar ideology, a similar cultural background, but who may not be from the same country. I may have more in common with some people living in Berlin, or in New York, or in South Africa, than with my neighbour in Barcelona. In that sense, I wanted to create a pavilion that had no country. Again, it is not something so much wanted as unavoidable because I have been living for twenty years outside of Spain. I never had this feeling of outside/inside because I often return to Spain. But the people I work with and the languages I speak are from many different countries. So, it would be meaningless to force these people to represent Spain. “Exhibiting”, as the very word means, has an idea of prize in it. You put everything to show off: lighting, labels, logos… This is something I could not do, because I just don’t believe in it. So, the idea of occupation was the alternative. I could not be exhibited, but my work occupies the pavilion. This is just a more accurate way to describe it.

SM: In which ways did the concept of occupation determine the setting of the work?

DG: In the pavilion, an important decision was not to use the regular construction devices of an exhibition, which, whether it is through fake walls or fake lights, are always focused on the idea of showing. I find this very unidirectional; it instructs us where we have to look at. It is something I could not find myself to fit in. Hence, there was the decision to use the space as it was: we broke all the fake walls and used only natural light. Another important decision was not to touch the walls: nothing would go on them. I wanted everything to be free standing and ready to go. Some people find it clumsy or unprofessional, which is ok to me. What was important for me was not to create an authoritarian exhibition structure. It is like camping somewhere: you put the things and the next day you go away and no one will remember anymore what was there. In that sense, it was a strong decision not to have my name on the walls. The ministry had of course to place the official logos on the wall, but by a happy accident, that did not happen either. So, the walls are completely white except for the poster presenting the schedule of the performance. The poster is ok because it is like what you find in the street and also because it gives a lot of information. So, the project has to do with a certain idea of alternative, because of the intention I have just described.

SM: It also carries an important notion: that things are not stable, but in a constant process of moving and changing.

DG: Exactly. This is also true for the films because they are projected onto portable spaces. They are a nightmare because everybody moves them and they are constantly askew. But it was our decision that we would not touch the space. It’s the same with the floor that constitutes the stage. It’s a structure that you can pack up completely. So, it is not ideal for very heavy performances because it is fragile. It is made of an aluminium frame and you can pile it up at the end.

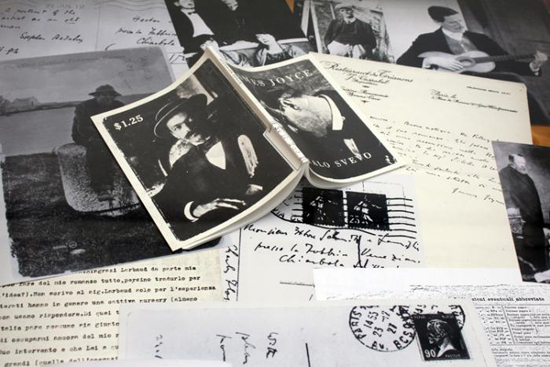

SM: What is the relationship between the pavilion’s different spaces – the central platform and the peripheral rooms with objects and films? And what is the status of the objects shown?

DG: the idea was not to make an exhibition in the traditional sense of showing works. The description of the piece is a performance and an archive. The archive is exclusively made of things that will be used in the performance. There are no works there. You have for instance the objects of the beggar. The beggar’s things have been shown in different exhibitions but always as performance objects. You also have books. There is no difference between something that has once been shown as an artwork and other things that were in my library or on my desk. And then, there is a big part of things that have been brought or have a relation to people who will be in the performance. So, bound together, all the things around are used in the performance. You take them, you put them back, sometimes the performers bring things, new things come in, and so, it’s a moving archive. There are all sorts of things: books, pictures, writings, objects… They all have been at a certain moment at the centre of the stage. And then the idea of the stage is something very natural in a performance and I also wanted to create an image that would be something like a logo, in the sense that every picture you took would have this big letter saying “the inadequate”. Writing the title of the work on the floor where the performance happens is something I have done in other performances. It’s a kind of enormous label that puts a stamp on everything. And this, for me, was a very traditional way of giving unity to the work.

SM: Can we understand it as a space to be activated?

DG: Yes. For me, it is very important – and it’s normal in the work I do – that the work is not ready on the first day. So there is a certain dynamic. There is a schedule and every day, things are happening. For instance, in Instant Narrative, someone constantly notes down everything happening in the space. The text is potentially infinite, and every month I print the 500 pages produced. The public can read them and get a very clear image of the amount of time that has passed by in that space. This gives a very physical presence of the time. When someone comes in now, he sees someone writing and four very thick books on the table. On the one hand, this gives an idea of the time: it is not something that was born the moment you came in and will disappear the moment you walk out, but something that exists there. On the other hand, it gives the idea that you have entered a system that exists independently of you and when you leave, it will keep going. I believe this is opposite to the conventional idea of exhibition.

It was also very important that there was an agenda with people coming to converse. The idea was to have conversations and not lectures: they’re not recorded, not amplified, not translated. The notion of lecture always implies the delivering of knowledge to someone who does not have that knowledge. In this work, it’s really about getting together and having a conversation. The meaning is not determined in advance but the list of people and the things that are discussed are giving the meaning to the work. So you are slowly drawing the outlines of the figure. It is something that is done in six months rather than something that was done from the beginning. I can see that it functions in the sense that the content gets more and more determined.

On marginality and the position of the artist

SM: The Inadequate partly takes its origin in your Mad Marginal project which you initiated in November 2009. In the project, you made references to artists as well as figures from all sorts of disciplines, such as the so-called anti-psychiatrists, to investigate the idea that marginality in art is a political position. The project has taken a variety of forms, among which talks, conversations, a historical research, a publication. Where does the whole question of marginality come from in your work?

DG: It comes from observing certain patterns that repeat themselves. For example the idea that an author, be it an artist or a writer, by nature adopts a marginal position, simply because you have to keep yourself out of the mainstream in order to see it. This is a very simple idea that was very well reflected for instance in the position that James Joyce adopted while walking in the street: he was always leaning against the wall and watching the people passing by. This is to me the typical position of the artist, someone who watches the others busying themselves and is, by nature, outside of them. He stays outside the normal state of things. Hence the impossibility to commit to things that other people do normally commit to, like a successful career or a family. This has always been very contradictory in the life of artists. In a way, it is a definition of the artist as being inapt. This quality of being inapt is repeatedly found in novelists, poets, etc.

And then, there is this provocation, or wonder, about the idea of audience and author. I believe that audience and author must be the same yet, at the same time, different. You need to share certain trends in order to be understood, such as a similar education, a similar provocation or contemporaneity, so that the audience can understand what you’re talking about. But at the same time, they cannot be exactly the same because the audience would get bored. So how an artist looks for its public is a typical avant-garde idea. For instance, success is the opposite of quality. This is something that has always been there but was especially strong with the avant-gardes, such as Surrealism and Dadaism: the idea of despising the bourgeois by putting yourself in a position of hate towards bourgeois success. It was something that interested me very much because it seemed like the more you hated them, the more they liked you. What interests me is how it evolves with time, taking as an example the figure of Lenny Bruce, who died of success. He got it very well when his audience was not that different from him: people who went to night clubs, who were used to inter-racial relationships. But the moment his audience got too big, people got offended because he was using a language that was not tolerable, not acceptable and then they said he was obscene. So the moment when an audience gets too big, then the artist is condemned. Within this kind of constant equilibrium and negotiation is the idea of marginality. You cannot please every crowd, or it will kill you. And this reflection is also connected to the idea of language, of politics… We must be aware, for instance, that the declared purpose of psychiatric treatment is not to make someone sane but to make someone ready to work.

SM: So your interest in marginality is directly connected to your position as an artist?

DG: It’s connected to my position as an artist but it’s also a study of certain cases.

SM: What is for you the position of the artist, then?

DG: The position of an artist is basically to think. But this is also the position of everyone. The artist is somehow an extreme example of mankind. Basically he does what anyone should do but because of a certain conception of the psyche he or she devotes all his time or her time to that.

SM: Some artists choose to concentrate on pure aesthetics…

DG: I think that’s another misconception, because pure aesthetics doesn’t exist either. Artists often have to answer questions like: in which way your presentation differs from a presentation of “just paintings”. But “just paintings” doesn’t exist because when you present, let’s say, in the most conventional way, you are presenting not only the paintings; the paintings are significant for a certain idea of art, a certain economic idea, a certain idea of the public. So in the end you are showing exactly the same as I do.

SM: Your work often challenges the traditional relationship spectators have to art. This is particularly true with The Inadequate: the work is developed over a period of six months so that no one will ever be able to see it in its entirety; the visitor entering the space also becomes part of it (momentarily being, for example, the subject of Instant Narrative). Is there an intention of initiating an alternative relation to art?

DG: Most of the time, I’m very surprised of what the usual relation most visitors have to art is. Many people find this space [the pavilion] empty, which obviously is not. So what kind of expectations do these people have about art? During my education as a young artist in the Netherlands and Belgium, I was taught by teachers with whom the discussion was not about whether this should be green or blue, but about the position of the artist. They were filmmakers and artists you can call conceptual, although I think it’s not a correct way of naming them because it’s a very reductionist term. So, I grew up in an artistic tradition that can be traced to, for example, Marcel Broodthaers, Stanley Brouwn, Art&Project, Bas Jan Ader or the Wide White Space. In that tradition, in which there are a lot of empty spaces, art is about a gesture of the artist, a position that the artist occupies, and not about the object; the object was an accidental signifier.

In that sense, to understand the position of the artist becomes my expectation when I go to see an exhibition well, if I have any expectation at all, because I think the less expectation you have, the better. So you go there to understand the position of this artist and not to decide I like this or I don’t like that: for me, it is not a shop. You are there with an attitude of curiosity to discover something. I have a positive attitude when I enter an exhibition space in the sense that I expect something new and joyful and it is not my attitude to go there to judge whether it would be nicer if things were higher or lower. So, this is where I come from and I’m very surprised at the expectations of other people. For me this is normal, this is what I understand as art, but surprisingly enough, I see that this is not what the majority of people think. I will never accommodate with the vision of these people, and in that sense we are condemned not to meet, we are condemned to be inadequate for ever.

So, if there was something I really wanted [for The Inadequate] was that judgment was impossible. It’s completely absurd to judge a manuscript of Joyce. It’s completely absurd to judge a theatre poster. If you say it’s not art, then I say it’s not. There is nothing there that you can point this is art, this is not art.

Blurring boundaries

SM: The Inadequate, as most of your work, directly puts into question the validity of a separation between art and life.

DG: This is a question that has always puzzled me because to me such a separation doesn’t exist. So I always wonder why people think so much about that because it is obvious that life doesn’t stop when you enter an exhibition space. There is life there as much as there is in a kiosk. There is something that I encounter very often with young artists and the so-called “revolutionary artists” that they want to bring art to the real life. But that doesn’t exist. There is as much real life in a collector’s house or inside a museum. There is no reason to believe that the street has more life than those places. To me there’s not a place without life. In a cemetery, as much as in any other place, there are things happening, rules to be understood, etc. What is interesting is to know what are the rules governing life in art institutions but it doesn’t mean that those places are lifeless.

SM: So, if the determination as to where art starts and stops is not an issue, what, then, is the nature of the artistic experience that you are looking for?

DG: It is more about having a certain communion with a state of things. There is another big misunderstanding related to what I meant when I said “you don’t have to understand art”. Most people thought it was very arrogant. Going back to the idea of language, I might listen to a language that I don’t understand at all and be completely impressed by the beauty of it. I may even feel the beauty of it even more because I don’t understand it. In the same idea, I have seen many pieces of art which I never could say I understood. I even think it is impossible in an artwork to say “this is what the artist wants”. You can reach a point of recognition in the sense that you understand the mood or the attitude of the artist. I can even say that I never have so much pleasure as when I see an artwork which I have no clue of what it is about. I’ve never closed my mind to be annoyed about it but keep wondering, because I am sure there is something behind. I never think the artist might be making fun of me or treating me as a fool. I think an artist does what he or she thinks has to be done.

SM: Do you recognize the existence of a formal beauty as well?

DG: I think beauty only exists in ideas. Let’s take people as an example. When you say someone is beautiful, you can’t really point to one particular aspect like perfect proportions or whatever else, but there is something in general, something in the way of talking or moving the body. I think it is similar with artworks.

SM: Whether it is between actor and spectator, art and life or fiction and reality, the very notion of the boundary is almost systematically put into question in your work. What is exactly the issue in maintaining such a state of indeterminacy as to what things exactly are?

DG: It has to do with the idea of truth: this is the way things are! As art, theatre has a lot of conventions. These conventions have always existed. For instance, you have actors among the public who clap. For it to work, the real audience shouldn’t know they are actors; otherwise they would not believe them and would not join the clapping. It has to do with the idea of truth and with questions about when an actor stops acting, when he addresses the audience, when he “breaks” character… These are all very interesting concepts to me because they deal with the nature of representation. And you have to break it to understand how it works. In his work of the 1960s and 1970s, Peter Handke really challenged the conventions of theatre by accentuating them. When you accentuate something very much, it reveals the non-sense of it. So, for instance, Peter Handke would forbid the entrance of people who were not properly dressed in an avant-garde theatre festival that was completely non-sensical, but which made people aware of these conventions.

SM: So it is truth to acknowledge that things cannot be fully defined?

DG: Everybody knows that!

SM: How is this connected to the apparent antagonism between reality and fiction in your work?

DG: I believe there is nothing that can represent reality because you can not face reality 100%. Reality is not understandable by nature. There is also nothing that is 100% fictional because every fiction has a foot in reality. I believe that fiction and reality are two notions in constant negotiation. And so is it in my work: some things are more towards fiction, some are more towards reality. Something psychiatry is very clear about is that you have to build a character for yourself and it is unclear how much reality is put into that character.

SM: So it is not so important whether something is real or whether it is fictitious?

DG: I think that everything is created for a purpose. If something functions for what you want, then it is ok. It means that if the role you have given to yourself makes your life happy and completely full, then it is ok. If it doesn’t, then you have to look for another role. It is all about surviving in the end. When you say it doesn’t matter, it matters as long as it helps you. If you’re not happy, you have to change the composition.

SM: In that respect, are fiction and reality of equal importance?

DG: Yes, they are. But it has to be discussed case by case. There are some situations where fiction is more valuable than reality and there are some situations where it is the contrary.

SM: Thank you!

About the artist

Dora García was born in Valladolid (Spain) in 1965. She lives and works in Barcelona.

Her recent solo exhibitions since include: 2011- L’inadeguato, Lo Inadecuado, The Inadequate, 54th Venice Biennale, Spanish Pavillion (curator: Katya García-Anton). 2010 – For Nothing Against Everything, OPA Oficina Para Proyectos de Arte A.C., Guardalajara, Mexico; I am a judge, Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland; The Deviant Majority, Galeria Civica di Trento, Trento, Italy; I am a Judge, Index, The Swedish Contemporary Art Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden. 2009 – ¿Dónde van los personajes cuando la novela se acaba? [Where do characters go when the story is over?], Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. She also participated in There is always a cup of sea to sail in, Sao Paulo Biennial (2010), Le spectacle du quotidien, Biennale de Lyon (2009), Revolutions – Forms That Turn, Sydney Biennial (2008), and Skulptur Projekte Münster 07, Germany (2007).