PHDTHESISbyDrBucknerKomlaDogbe submittedattheUniversityofStAndrews DATE 1989 SOURCE StAndrewsResearchRepository©The Author

THEINFLUENCEOFAFRICANSCULPTUREONBRITISH ART,1910-1930

BucknerKomlarDogbe

AThesisSubmittedfortheDegreeofPhD atthe

UniversityofStAndrews

1989

Fullmetadataforthisitemisavailablein Research@StAndrews:FullText at:

http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/

Pleaseusethisidentifiertociteorlinktothisitem:

http://hdl.handle.net/10023/7118

Thisitemisprotectedbyoriginalcopyright

THE INFLUENCE OF AFRICAN SCULPTURE ON BRITISH ART

1910 TO 1930

Buckner Komla Dogbe

A Thesis presented in the Department of Art History in the University of St. Andrews for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY.

1988

ABSTRACT

This thesis aims to discuss the influence of African wood sculpture on British art from 1910 to 1930. It proposes that the works, tastes and pronouncements of various 20th century British artists betray this influence and that although the British artists did not initially understand the conceptual foundations of African sculpture their limited knowledge was just sufficient for the modernization of British art through the adaptation of the formal qualities of African art.

In assessing the validity of these propositions the thesis examines the factors and issues that facilitated the influence. Chapter 1 discusses the formal qualities of African wood sculpture that attracted the British artists. It outlines the unusual figural proportions, the free and direct use of planar, linear and solid geometry, the treatment of material and its surfaces.

The conceptual foundations of African sculpture are generally outlined in Chapter 2. The extent to which the British artists understood these foundations is also discussed.

Chapter 3 concerns the introduction of African sculpture to Britain and discusses the development of the anthropological and subsequent aesthetic interest that it aroused. Both the Post-Impressionist Exhibitions and the Omega Workshops which facilitated its influence are examined. Chapter 4 examines the concept and attempts to categorize the nature of this influence.

The last three chapters act as case studies in which the impact of African sculpture on Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska and Henry Moore is examined. The conclusion discusses the term 'Primitive' and the British artists and the 'Primitive' • ..

Declarations

I, Buckner KomIa Dogbe, hereby that this thesis which is approximately 81,000 words in length has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree.

Signature •

B. K. Dogbe

I was admitted as a Research Student under Ordinance No.12 on 10 October 1984 and as a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy on 24 June 1985; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between October 1984 and June 1988.

Signature

B. K. Dogbe

Copyright Declaration

In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker.

Signature

B. K. Dogbe

I hereby certify that the candidate, Buckner Komla Dogbe, has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolutions and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of st. Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In order to provide me with the best facility and supervision in my research, Professor Martin Kemp suggested the title "The Influence of African Sculpture on European Art" when I applied for admission into the Department in 1982. When I arrived in St. Andrews two years later in November 1984, my supervisor Dr.Christina Lodder suggested the present subject, for which I am grateful to her. Nevertheless Professor Kemp has shown continued enthusiasm in the progress of my research and I appreciate his encouragement.

I am also indepted to several people for assistance in the preparation of this thesis. Especially I wish to thank Peter, Monica and Elizabeth Wengraf, who unreservedly gave me access to their archives, photocopying machine and African collections at the Arcade Gallery, Royal Arcade, London. This proved of great inspiration and an enormous privilege.

I wish to thank Dr D.H.A.Kaferly for introducing me to the basics of the computer and also Mrs Philippa Hill and Ms Dawn Wadell who have helped me in many ways.

Many scholars have also guided and helped my research. Dr.Elizabeth Cowling provided me with many sources of information on primitive art and introduced me to other scholars. Ms Jane Bywaters gave me useful information on the Museums with Ethnographical collections in Britain. Dr George H.A.Bankes also willingly shared light on the ethnographical holdings of museums in the United Kingdom. Dr Terry Friedman has been tremendously helpful by giving me access to the collections and archives of The Henry Moore Centre for the Study of Sculpture, Leeds. Dr Evelyn Silber most willingly shed light on Epstein's work and introduced me to other scholars including Mr Michael Paddington who was also helpful on the same subject. Mr Malcolm McLeod

gave me valuable information on the African sculptures in Epstein's collection.

Among the staffs of several institutions, archives, museums and galleries who deserve especial thanks for their courteous and generous response to my requests are: the staffs of King's College Library, and the Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge; The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Manchester Museum, Manchester; City Art Gallery, Manchester; Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; The Courtauld Intitute Galleries, University of London; The Henry Moore Centre for the Study of Sculpture, Leeds; City Art Galleries, Leeds; City Museum, Leeds; The County Museum, Liverpool; Pitt Rivers Museum and Department of Ethnology and Prehistory, University of Oxford; City Museums and Gallery, Birmingham; City Museum and Gallery, Bristol; The Museum of Mankind, London; The British Museum, London; Ipswich Museum, Ipswich; Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norwich; Victoria and Albert Museum, London. And abroad I wish to thank the staff of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

I am grateful to the Staff of the Computer Laboratory of University of St. Andrews as well as the Inter-Library Loan Section of the University of St.Andrews Library whose remarkable efforts have immensely improved many aspects of this thesis. MY sincere thanks also go to the staff of Photographic Unit of the University of St. Andrews whose marvelous work has improved the quality of the photographs of this thesis, which I personally took without the proper skill.

I am also grateful to Mr Tom Normand who was briefly my supervisor from July 1987 to January 1988, for his useful suggestions. Finally I greatly thank Dr Anthony Parton who took over the supervision of the thesis from Mr Normand, and whose encouragement and quick responses led to its ultimate completion.

In the list below items are categorised according to the following system: tribe and country or artist, subject or title, medium, size, location, and in the case of African sculptures the date of acquisition by the museum or gallery if known.

FIG.1.1. Baluba, Zaire, Female Figure (back and front), wood, 18ins (46cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1910.

FIG.1.2. A Diagram of Formal Analysis of African Wood sculpture. Louis Perrois, La Sculpture Traditional du Gabon, Paris, 1977, p.

FIG.1.3. Stages of Carving Showing Examples of Proportions. Louis Perrois, La Statutaire Fan Gabon, Paris,1978, as Fig.82. After 33. After

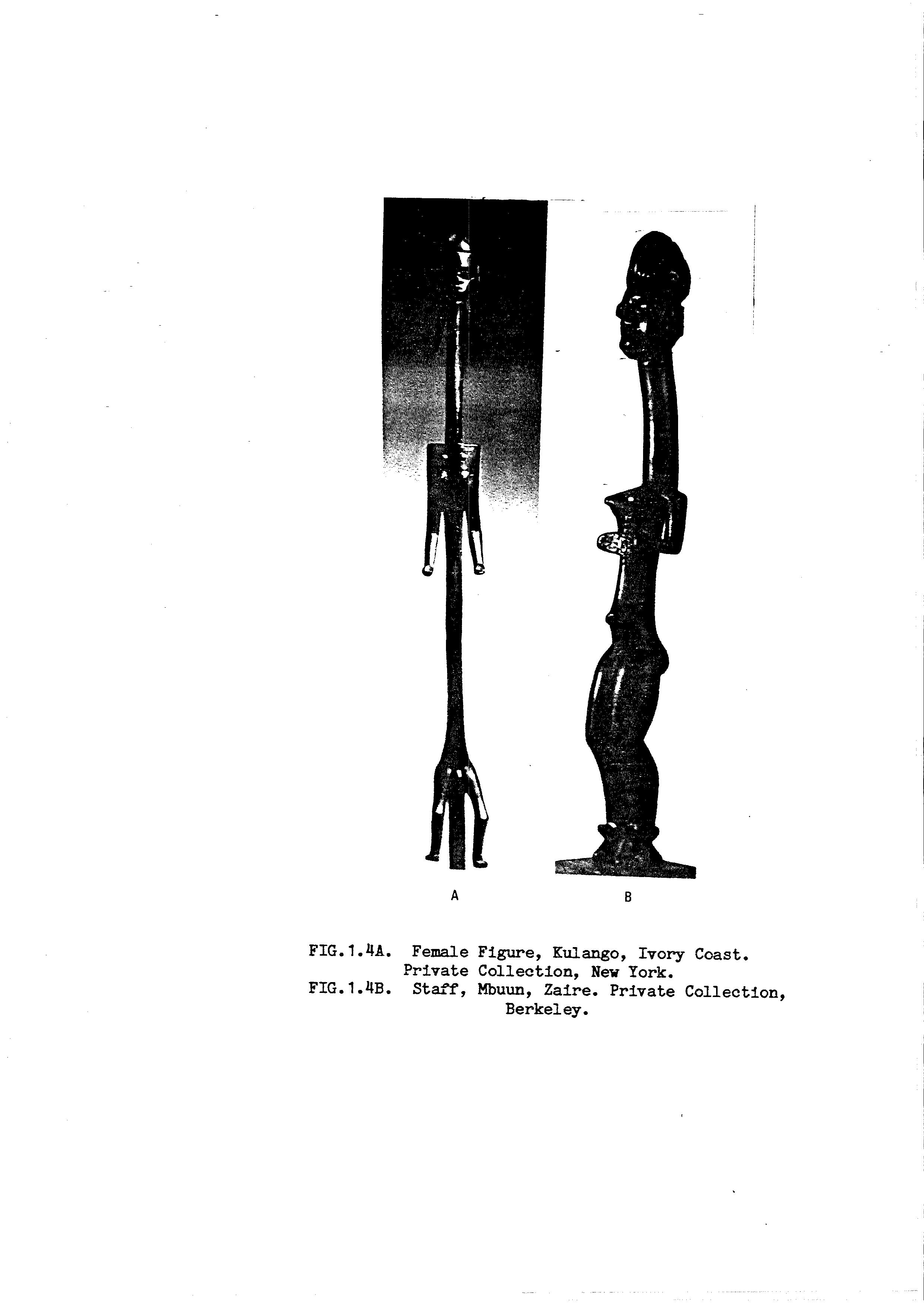

FIG.1.4A. Kulango, Ivory Coast, Female Figure, wood, 18ins (46cm), Fried Collection, New York. Reproduced in William Rubin ed., "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art, New York, 1984, p. 530.

FIG.1.4B. Mbuun, Cameroon, Staff, Wood and metal, 33in (83.8cm), ErIe Loran Collection, Berkeley. Reproduced in Rubin ed., "Primitivism", p. 530.

FIG.1.5. Examples of Types Head-shapes of African Wood sculpture.

FIG.1.6. Types of Concave Faces in African Sculpture. After D.E.McCall and Edna Bay, Essays in African Iconology, Boston, 1975, pp. 253-7.

FIG.1.7. Two Masks with Heart-shapes Ending in Upper and Lower Lips Respectively. British Museum, London.

FIG.1.S. Bamum, Cameroon, Headdress, wood and fibre, Pierre Harter Collection, Paris. Reproduced "Primitivism", p. 156.

FIG.1.9. Bakuba, Zaire, Ndob, wood, 21.5ins (54.6cm), London, acquired 1909. 11.75ins (30cm), in Rubin ed., British Museum,

FIG.1.10. Basongye, Zaire, Standing Male Figure, wood, 21.75ins (55cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1905.

FIG.1.11. Dogon, Mali, Female Figure, wood, 23.6ins (60cm), Musee de I 'Hamme, Paris, acquired 1906.

FIG.1.12. Mende, Sierra Leone, Female Figure (front and side), wood, 46.5ins (118cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1901.

FIG.1.13. Eye Types of African Sculpture.

FIG.1.14. Nose Types of African Sculpture.

FIG.1.15. Mouth Types of African Sculpture.

FIG.1.16. Ear Types of African Sculpture.

FIG.1.17. Bajokwe, Angola, Figure, wood, 11ins, (28.9cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.1.18. Breast Types of African Sculpture.

FIG.1.19. Types of Male Sexual Organs in African sculpture.

FIG.1.20. Baluba, Zaire, A Female Figure, wood, 21 ins (53.3cm), W.O.Oldman Collection, London.

FIG.1.21. Az and e , Central African Republic, Female Figure, wood, 20.75ins (52.7)cm, British Museum, London.

FIG.1.22. Balwena, Congo, Ritual Female Figure painted Red and Black on The Chest, wood, 11ins (28.9cm), Musee Royal de l'Afrique Centrale, Tervuren, Belgium.

FIG.1.23. Fang, Gabon, A Woman on Horseback Carrying a Bowl, wood, 38ins (96.5cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.1.24A. Bateke, Congo, Human Figure, wood, 6.75ins (17.1cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1906.

FIG.1.24B. Bateke, Congo, Fetish Figure, wood, 5ins (15.25cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1906.

FIG.1.24C. Bateke, Congo, Fetish Figure, wood, 5.75ins (14.6cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1906.

FIG.1.25. Bangwe, Cameroon, Dancing Royal Couple, wood. 34.5ins (87.6cm) and 33.25ins (87.1cm), The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. Reproduced in Hugh Honour, A World History of Art, London, 1983 as Figs 18 and 16.

FIG.1.26 Ashanti, Ghana, Akuaba, wood, 13ins (33cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.1.27. Bakota, Congo, Reliquary Figure, wood and brass, 26ins (66cm), British Museum 1924, London.

FIG.1.28. Yoruba, Nigeria, Two Ikenga, wood, 18ins (45.7cm) and 18.25ins (46.4cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1873.

FIG.1.29. Senufo, Ivory Coast, Mask, wood, 36ins (91.5cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.1.30. Bamileke, Cameroon, Throne, wood, 46ins (116.8cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1900.

FIG.1.31 Yoruba, Nigeria, Epa Mask (front and side), wood painted red, blue and white, 54ins (137.1cm), Leon Underwood Collection, London. Reproduced in Leon Underwood, Masks of West Africa, London 1948, as pl.34.

FIG.1.32. Ogoni, Nigeria, Mask, wood, fibre and cane, (41.2cm), British Museum, London. 16.25ins

FIG.1.33. Wazaramo, Tanzania, Human Figure, wood, 33.5ins (85cm), Museum fur Volkerkunde, Berlin, acquired 1889. Reproduced in Fagg, Tribes and Forms in African Art, London, 1965, p. 119.

FIG.1.34. Ijo, Nigeria, Memorial Screen, wood. British Museum, London, acquired 1910.

45.5ins (115.6cm),

FIG.1.35. Bambara, Mali, Chi wara Antelope Mask, wood, 29.5ins (75cm),

M.Nicaud Collection, Paris. Reproduced in Pierre Meuaze, Africa Art: Sculpture, London, 1968, p. 48.

FIG.1.36. Swazi, Namibia, Milkpot, wood, 19x15ins (48x38.1cm), Private Collection, London. Reproduced in Werner Gillon, A Short History of Africa Art, London, 1984, p. 206, as pl.253.

FIG.1.37A. Bambala, Congo, Headrest, wood, 10.75ins (27.3cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1907.

FIG.1.37B. Ashanti, Ghana, Stool, wood, 28ins (71.1cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1880.

FIG.1.38. Bagirmi, Chad, Doll, wood, 8.75ins (22.2cm), Charles Rat ton Collection, Paris. Reproduced in Fagg, Tribes And Forms, p. 69.

FIG.2.1. Dogon, Mali, Sanctuary Shutter, wood, 29x18ins (73.1x45.7cm). Private Collection, Cannes. Reproduced in Meuaze, African Art, p. 153.

FIG.2.2. Dogon, Mali, Mythical Ancestors (front and back), wood, 26.25ins (66.5cm), Rietberg Museum, Zurich. Reproduced in Elsy Leuzinger, The Art of Black Africa, London, 1972, pl.A20.

FIG.2.3. Yoruba, Nigeria, Shango Sacred Staff, wood, 16.6ins (41.9cm), Ipswich Museum, Ipswich.

FIG.2.4. Bambara, Mali, Chi wara Headdress, wood, 40ins (101cm). Reproduced in Ladislas Segy, Masks of Africa, London, 1960, as Fig.38.

FIG.2.5. Bambara, Mali, Two Masked Dancers with and Female chi wara Headdresses. Reproduced from Segy, Masks of Africa, as Fig.37.

FIG.2.6. Senufo, Ivory Coast, (96.5cm), Private Collection, "Primitivism", p. 130.

Deble (Rhythm Pounder), Paris. Reproduced from wood, 38ins Rubin, ed.,

FIG.2.7A. Yoruba, Nigeria, Odudua (Fertility goddess), wood 30.5ins (76.1cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1912.

FIG.2.7B. Yoruba, Nigeria, Odudua (Fertility goddess), wood, 27.5ins (64.7cm), Horniman Museum, London, acquired 1925.

FIG.2.8. Baga, GUinea, Nimba Mask, wood, 46ins (116.8cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.2.9. Baga, GUinea, Nimba Figure, wood, 24. 75ins (63cm), Rietberg Museum, Zurich. Reproduced in Elsy Leuzinger, The Art of Black Africa, London, 1972, pl.E26.

FIG.2.10. Bundu, Sierra Leone, Bundu Mask, 15ins (38.1cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.2.11. Bundu, Sierra Leone, Bundu Staff, wood, 30ins (76.2cm), University Museum, Philadelphia. Reproduced in Paul Wingert, The Sculpture of Negro Africa, New Yeork, 1950. pl.11.

FIG.2.12. Yoruba, Nigeria, Bowl, wood, 15ins (38.1cm), British Museum.

FIG.2.13. Types of Fetish Figures.

FIG.2.14A. Yoruba, Nigeria, Gelede Mask, wood, 40ins(101.6cm), British Museum.

FIG.2.14B. Yoruba, Nigeria, Egungu Mask, wood 17.25ins (43.8cm), Rantenstrauch-Joest Museum, Cologne. Reproduced in William Fagg and Margaret Plass, African Art:Anthology, London, 1964, p. 90.

FIG.2.15. Baluba, Zaire, Kneeling Female Figure with Bowl, wood, 21ins (53.5cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1905.

FIG.2.16. Yoruba, Nigeria, Ibeji Figures, wood, British Museum, London.

FIG.2.17. Bawongo, Congo, Bowl and Lids with Animal and Human Forms,

FIG.2.18. Types of Bakuba Wooden Cups ...

FIG.2.19. Sakal ave , Madagascar, Grave Post, wood, 38ins (96.5cm), Musee de l'Homme, Paris.

FIG.2.20. Types of African Carved Drums.

FIG.2.21. Bamileke, Cameroon, Door Frame, wood, 77.4ins (200cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.2.22. Sculptures showing Tottoo, Scarification and Cicatrices.

FIG.3.1. Yoruba, Nigeria, Equestrian, wood, 12.5ins (31.8cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1830.

FIG.3.2. Baluba, Zaire, Stool (front, back and side), wood, 25ins (63.5cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1901.

FIG.3.3. Fang, Gabon, Spirit Head, wood, 10.6ins (27cm), The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia. Reproduced in Kenneth Clark, ed., Last Lectures London, 1939, as pl.89.

FIG.3.4. Henri Matisse, Girl with Green Eyes, 1909, Oil on canvass, 26x20ins (66x50.8cm), San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francesco. Reproduced in Ian Dunlop, The Shock of The New, London, 1972, p. 151.

FIG.3.5. Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman, 1909, gouache on paper, 24x18ins (61x45.7cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

FIG.3.6. Pablo Picasso, Head and Shoulder of a Woman, 1909, gouache on paper, 25.25x 19.12ins (64x48.5cm), Gallerie Beyer, Basel.

FIG.3.7. Pablo Picasso, Buffalo Bill, 1912, oil on canvass, 18.25x13ins (46x33cm). Present collection unkown.

FIG.3.8. Henri Matisse, La Serpentine (front and back), 1912, bronze, 21.5in (54.6cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

FIG.3.9. Bambara, Mali, Seated Ancestor Figure, wood, formerly Matisse Collection now in Private Collection. Rubin ed., "Primitivism", p. 229.

24ins (61cm), Reproduced in

FIG.3.10. Duncan Grant, The Queen of Sheba, 1912, oil on wood, 47.25x47.25ins (120x120cm), Tate Gallery, London.

FIG.3.11. Pablo Picasso, Head of a Man, 1912, oil an canvass, 24x15ins (61x38cm). Private Collection, Paris. Reproduced in Pierre Daix, Picasso: The Cubist Years 1907-1916, London, 1979, as Fig.468.

FIG.3.12. Ducan Grant, Couple Dancing, 1913, pencil and gouache, 30x15.5ins (76.2x39.4), Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

FIG.3.13. Pablo Picasso, Nude with Raised Arms, 1907, oil on canvass, 24x17ins (61x43.2cm), Thyseen-Bornemisza Collection, Lugano, Switzeland.

FIG.3.14. Pablo Picasso, Nude with Drapery, 1907, oil, 60x39ins (152.3x101cm), Hermitage Museum, Leningrad.

FIG.3.15. Duncan Grant, Head of Eve, 1913, oil on board, 29. 75x25ins (75.5x63.5cm), David Garnet Collection. Reproduced in Roger Fry, Duncan Grant, London, 1924, as pl.8.

FIG.3.16. Duncan Grant, Adam and Eve, 1913, oil, 84x132ins (213.3x335.2cm), damaged in the Tate Gallery flooding in 1928.

FIG.3.17. Pablo Picasso, African Head, 1907, oil and sand on panel, 6.8x5.5ins (17.5x14cm), Claude Picasso Collection, Paris.

FIG.3.18. Pablo Picasso, African Head, 1907, oil on canvass, 7x5.3ins (17x8.14.3cm), Claude Picasso Collection, Paris.

FIG.3.19. Duncan Grant, The Tub, 1912, watercolour and tempera on board, 30x22ins (76.1x55.9), Tate Gallery, London.

FIG.3.20. African sculpture in Matisse's collection in his appartment at Hotel Regina, Nice. Reproduced in Rubin ed., "Primitivism", p. 237.

FIG.3.21A. Wyndham Lewis, Design for Drop-Curtain, 1912, and crayon, 12x15.3ins (30.5x38.9cm), Theatre Museum, Albert Museum, London.

FIG.3.21B. Wyndham Lewis, Indian Dance, 1912, black watercolour, 10.75x11.5ins (27x29cm), Tate Gallery. pencil, ink Victoria and chalk and

FIG.3.22. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Marquetry Tray, 1913, wood, 25.25ins (64cm), Charles L.Strong Collection, London.

FIG.3.23. Pablo Picasso, Dryad, 1908, oil on canvass, 72.75x42ins (185x108cm), Hermitage Museum, Leningrad.

FIG.3.24. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Bird Bath (two views), 1913, plaster, 10.5in (26.7cm), Mercury Gallery, London.

FIG.3.25. Dan, Liberia, Mask with Monkey Hair, 6ins (15.2cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1868.

FIG.3.26. Roger Fry, Mother and Children, 1913, painted wood, 11.25x9x4ins (28.5x23x10cm), private collection, London.

FIG.3.27. Roger Fry, Marquetry Cupboard, 1915-16, inlaid wood, 84x45.5x16ins (213.5x115.5x40.7cm), Lady Tredegar, London. Reproduced in Isabelle Ascombe, Omega and After, London. 1981, as pl.18.

FIG.3.28. Roger Fry, Essay in Abstract Design, 1914, oil and bus tickets on panel, 14.25x10.5ins (36.2x27cm), Tate Gallery, London.

FIG.3.29. Roger Fry, Tennis Players, Q1914, pencil on paper, 7.5x11.5ins (19x29.2cm). Private Collection, London. Reprpoduced in Judith Collins, The Omega Workshops, London, 1983, as pl.44.

FIG.3.30. Roger Fry, Reclining Nude, Q1914, pencil on paper, whereabout of original is unknown, photocopy in the Witts Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

FIG.3.31. Wyndham Lewis, Circus Scene, 1913, pencil, watercolour and gouache, 20.2x15ins (51.1x38.7cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

FIG.3.32. Wyndham Lewis, Omega Workshops Letter Head, 1913, printed paper, Whole sheet 9.8x8ins (25x20.3cm), private collection, London. Reproduced in Richard Cork, Beyond the Gallery, London, 1985, as Fig.161.

FIG.3.33. Wyndham Lewis, watercolour, 11.6x12.4ins London.

Theatre Manager, 1909, (29.5x31.5cm), Victoria pen, ink and and AI bert Museum,

FIG.3.34. Baga, GUinea, Nimba Headdress, wood with copper eyes, 25.25ins (64cm), Rietberg Museum, Zurich. Reproduced in Elsy Leuzinger, Art of Black Africa, London, 1972 as pl.E9.

FIG.3.35. Wyndham Lewis, Fire Place, 1913-14, painted side panels each 92.8x14.5ins (236x36.8cm), painted top panels each 9x86.25ins (23x219cm), mirror 67x61ins (170x155cm), private collection, London. Reproduced in Wyndham Lewis ed., Blast l (London), June 1914, as illustration vii.

FIG.3.36. Duncan Grant, Decorated Omega Plates, Q1914, earthernware with white tin glaze decoration, diameter 9.75ins (24.8cm), private collection, London. Reproduced in Isabelle Anscombe, Omega and After, London, 1981, as pl.26.

FIG.3.37. Pablo Picasso, Standing Nude and a Foot, 1909, 11.8x9ins (30x22cm), Musee Picasso, Paris.

FIG.3.38A. Frederick Etchells, Head, 1914, watercolour, 17x12ins (43x30.5cm), lost, Reproduced in Blast l as illustration x.

FIG.3.38B. Frederick Etchells, Head, 1914, watercolour 17x12ins (43x30.5cm), lost. Reproduced in Blast l as illustration ix.

FIG.3.39. Ulvira, Zaire, Mask, wood, 24ins (61cm), Courtauld Institute Galleries, London.

FIG.4.1. Wyndham Lewis, Three Figures (Ballet Scene), 1919-20, crayon and wate rcol our , 14,75x19.5ins (37.5x49.5cm), private collection. Reproduced in Walter Michael, Wyndham Lewis. Drawings and Paintings, London, 1972, p. 382, as pl.73.

FIG.5.1. Adrian Allinson, Mr Epstein doubting the authenticity of a South sea Idol, 1914, pen and ink, 20x20ins (50.8x50.8cm), Reproduced in Colour (London), November 1914, p. 142.

FIG.5.2. Fang, Gabon, "Brummer Head", (front and side), wood, 24ins (61cm), formerly Epstein Collection. Reproduced in Kenneth Clark ed., Last Lectures London, 1939, as Figs. 93 and 94.

FIG.5.3. Jacob Epstein, Tomb of Oscar Wilde, 1912, stone, Pere Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

FIG.5.4. Jacob Epstein, Tomb of Oscar Wilde, 1912, detail.

FIG.5.5. Assyrian, Winged Man-Headed Lion, from the Palace of King Assur-Nasid Pal, 880-860BC, Marble, 192.9ins (490cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.5.6. Jacob Epstein, Sketch for the Tomb of Oscar Wilde, 1910, .,eiy

pencil, 15x22.75ins (38.1x50.8cm), Anthony D'Offay Gallery, London.

FIG.5.7. Jacob Epstein, Sketch for the Tomb of Oscar Wilde, 1911, pencil, 11x11.5ins (27.9x29.17cm), Simon Wilson Collection, London.

FIG.5.8. Jacob Epstein, 19x8.25ins (48x21cm), Collection), Walsall.

Study Walsall for Girl Museum with Dove, 1906, pencil, and Gallery (Garman-Ryan

FIG.5.9. Jacob Epstein, Head, 1910, crayon and wash, 25.75x19.5ins (65x49cm), private collection, London. Reproduced in Richard Buckle, Epstein Drawings, 1962, pl.30.

FIG.5.10. Jacob Epstein, African Carving, c.1908-10, pencil, no size given. Photograph in the Witt$ Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

FIG.5.11. Jacob Epstein, Crouching Sun Goddess, 1910, limestone, 37.5ins (95.2cm), Nottingham Castle Museum, Nottingham.

FIG.5.12. Jacob Epstein, Sunflower, 1910, stone, 23x10.5x9.5ins (58.8x26x24cm), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

FIG.5.13. Fang, Gabon, Head, 22.8ins (58cm), formerly Epstein Collection, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Reproduced in Rubin ed., "Primitivism", p. 430.

FIG.5.14. Jacob Epstein, Maternity, 1910, stone, 82ins (208.3cm), Henry Moore Centre for the Study of Sculpture, Leeds.

FIG.5.15. Fon, Dahomey, RitualBowl, wood, 7ins (17.8cm), diameter 5.5ins (13.3cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1889.

FIG.5.16. Jacob Epstein, Cursed Be the Day Wherein I was Born, 1912, wood and plaster, 45.5ins (115.5cm), lost, photograph owned by the Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London.

FIG.5.17. Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, 1913, pencil and blue crayon, 16.25x21.75ins (41.5x55cm), Wasall Museum and Gallery, Walsall.

FIG.5.18. Analytical Study of Modigliani's Caryatid of 1913.

FIG.5.19. Jacob Epstein, A Nude Figure, 1913, 25.25x20.75ins (64.1x52.8cm), Epstein Estate, London. blue chalk,

FIG.5.20. Constantin Brancusi, First Step, 1913, wood, 44ins 115cm). Destroyed except for the head. Full figure reproduced in Rubin ed., "Primitivism", p. 348.

FIG.5.21. Bambara, Mali, A Male Figure, wood, 25.6inc (65cm), Musee de I 'Homme, Paris. Reproduced in Marius de Zayas African Negro Art, New York, 1916, as Fig.16.

FIG.5.22. Jacob Epstein, Mother and Child, (front and back), 1913, marble, 16.25ins (41.3cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

FIG.5.23. Fang, formerly Epstein York. Gabon, Reliquary Head, wood, 18.25ins (46.5cm), Collection now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New

FIG.5.24. Jacob Epstein, First Venus with Doves, (front and side), 1913, marble, 48.5ins (123cm), Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore.

FIG.5.25 Jacob Epstein, Second Venus with Doves, (side and front), 1914, marble, 92.5ins (235cm), Yale Gallery, Yale.

FIG.5.26. Dogon, Mali, Seated Figure, wood, 27.2ins (69cm). Formerly Epstein Collection now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

FIG.5.27. Jacob Epstein, Drawing for Birth, 1913, brush and ink, lost. Reproduced in Blast l, as illustration xxvi.

FIG.5.28. Jacob Epstein, Birth, 1913, stone, 12x10.5ins (30.5x26.6cm), Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

FIG.5.29. Jacob Epstein, Study for Man and Woman, 1913, pencil and wash, 24.25x16.5ins (61.1x41.3cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.5.30. Sakal ave , Madagascar, Funerary Post, wood, 39.75ins (101.cm), formerly Epstein Collection.

FIG.5.31. Jacob Epstein, Totem, 1913, pencil and wash, 24x16.5ins (61x42cm), Tate Gallery, London.

FIG.5.32. Jacob Epstein, Study for Rock Drill, 1913, pencil and red and blue crayon, 18x23ins (58.4x45.5cm), Anthony d'Offay Gallery, London.

FIG.5.33. Baule, Ivory Coast, Mask, wood, 35.8ins (91cm). Paul Guillaume Collection. Reproduced in The Burlington (London), Vol.36, No.205, April 1920, p. 168, as pl.1.

Formerly Magazine

FIG.5.34. Baule, Ivory Coast, Mask, wood, 35.75ins (91cm). Formerly Paul Guilluame Collection, Paris. Reproduced in Paul Guillaume and Thomas Munro, Primitive Negro Sculpture, New York, 1926, as Fig.28.

FIG.5.35. Jacob Epstein, Study for Rock Drill (back views), 1913, (A) crayon, 16x26.5ins (40.6x67.5cm), Anthony d'Offay Gallery, London. (B) Lost. Reproduced in Bernard van Dieren, Jacob Epstein, London, 1920, p. 237, as pI. XII.

FIG.5.36. Jacob Epstein, Study for Rock Drill (front views), 1913, (A) black crayon, 21x25ins (53.3x64.1cm). Tate Gallery, London. (B) charcoal, 16.75x26.5ins (42.5x67.5). Walsall Museum and Gallery, WalsalI.

FIG.5.37. Jacob Epstein, Rock Drill, 1914. Reconstruction 1973-74 by K.Cook and A.Christopher after the lost original, matal and wood, 98.5ins (250.1cm), Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham.

FIG.5.38. Jacob Epstein, Genesis, 1930, marble, 64ins (162.5cm). Granada Television Limited, London.

FIG.5.39. Dogon, Mali, Seated Female Figure, wood, no size given. Albert Barnes Collection, New York. Reproduced in Guillaume and Munro, Negro Art, as Fig.16.

FIG.5.40. Baule, Ivory Coast, Male Figure, wood, no size given. Albert Barnes Collection, New York. Reproduced in Guillaume and Munro, Negro Art, as Fig.21.

FIG.5.41. Jacob Epstein, Two Studies for Genesis, 1929, (A) pencil, 11x16.75ins (28x42.5cm). Private collection, London. Reproduced in Richard Buckle, Jacob Epstein. Sculptor, London, 1963, p. 153, as pl.236. (B) pencil, 11.25x17.5ins (28.5x44.6cm), Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham.

FIG.5.42. Dan-Ngere, Liberia, Mask, wood. 10.5ins (26.8cm). Formerly Jacob Epstein Collection. Reproduced in Evelyn Silber, Terry Friedman, et al., Jacob Epstein. Sculpture and Drawings, London, 1987, as pl.III.

FIG.5.43. Bakota, Zaire, Female Figure, wood, 23ins (58.4cm), Formerly Jacob Epstein Collection. Reproduced in Christies Sales catalogue, Egyptian. Greek and Roman Antigues and Primitive Works of' Art of' Af'rica etc. From Jacob Epstein Collection, London, 1961, Cat. No.13, pl.4

FIG.6.1. Yoruba, Nigeria, Divination Bowl, wood, 7.8ins (20cm), Bristol Museum, Bristol, acquired 1896.

FIG.6.2. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Ornament Mask, 1912, painted plaster, 30x27ins (76.2x68.5cm), Musee du Petit Palais, Geneva.

FIG.6.3. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, A Letter f'rom Gaudier-Brzeska with a Sketch of' Epstein's Tomb of' Oscar Wilde, 1912. Reproduced in Roger Cole, Burning to Speak, 1978, p. 22.

FIG.6.4. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Head of' a Young Man, 12x9.5ins (30.5x24.1cm), Stadt Bielef'eld, Germany. Burning to Speak, p. 56, as pl.9.

1912, sandstone, Reproduced in Cole

FIG.6.5. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Redstone Dancer, 1913, stone, 17x9x9ins (43.2x22.9x22.9cm), Kettle's Yard, University of' Cambridge, Cambridge.

FIG.6.6. Bambala, Congo, Fertility Doll, wood, 2.25x3.75xO.5ins (5.4x9.5.x1.2cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1907.

FIG.6.7. Bapende, Congo, Mask, wood, 16.8ins (42.8cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1907.

FIG.6.8. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Study f'or Redstone Dancer, 1913, watercolour and charcoal, 18.7x12.25ins (48x31cm), Musee d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges, Pompidou, Paris.

FIG.6.9. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Portrait of' My Father, 1910, dry clay , painted bronze. 10.75ins (27.2cm), Museedes Beaux Arts, Orleans

FIG.6.10. Auguste Rodin, Man with Broken Nose, 1864, bronze, 9x9x10ins (22.8x22.8x25.4cm), Rodin Museum, Paris.

FIG.6.11. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Imp (two views), alabaster, 16ins (40.6cm), Tate Gallery, London. 1914, vained

FIG.6.12. Bambala, Congo, Female Figure, wood and human hair, 20ins (50.7cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1907.

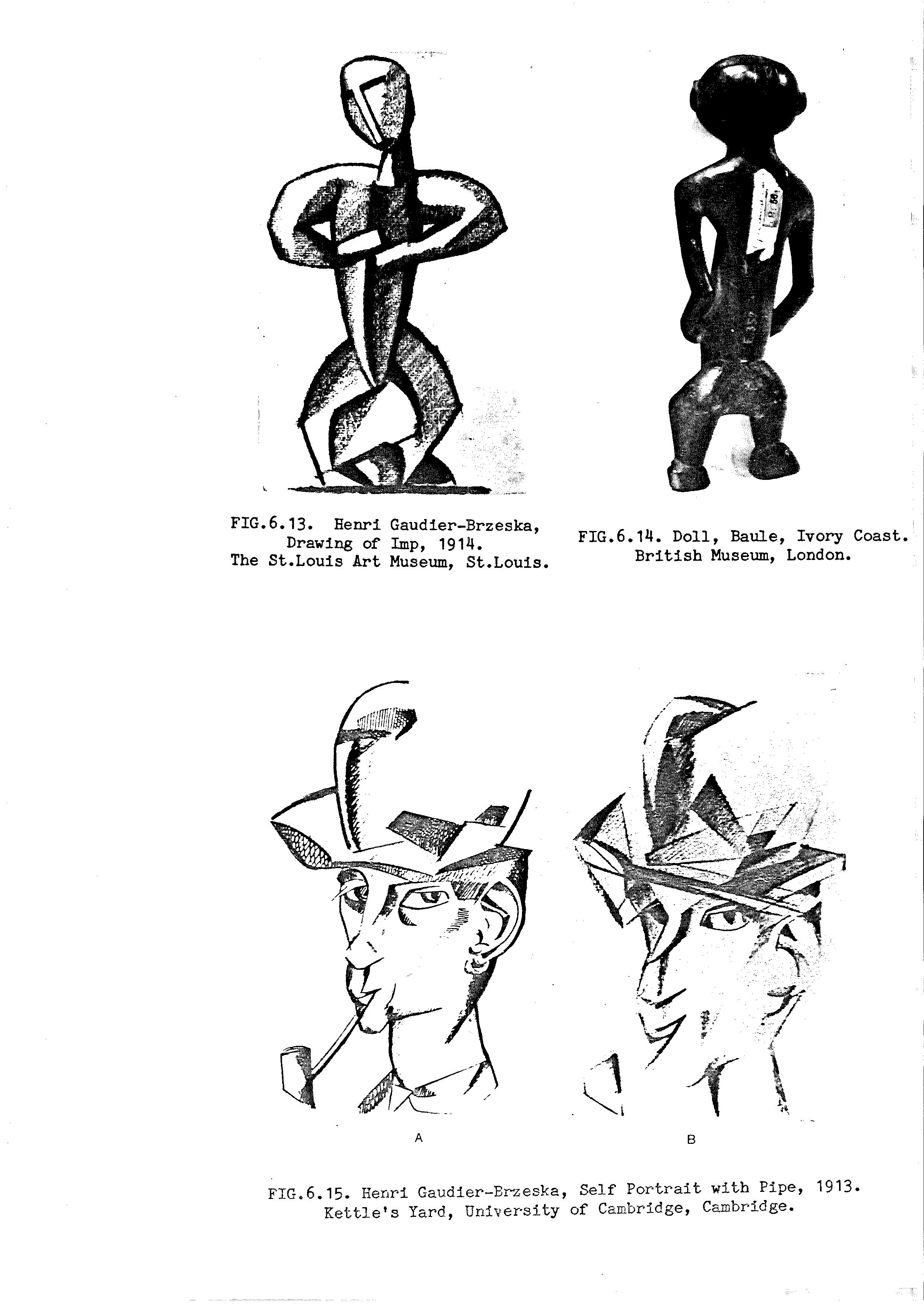

FIG.6.13. Gaudier-Brzeska, Drawing f'or Imp, 1914, charcoal, 9.5x6.25ins (24.1x15.6cm), The St.Louis Art Museum. Reproduced in Alan G.Wilkinson, Gauguin to Moore: Primitivism in Modern Sculpture, OntariO, 1981, p. 125.

FIG.6.14. Baule, Ivory Coast, Doll, wood 16ins (40.5cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1908.

FIG.6.15A. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Self' Portrait with Pipe, 1913, pencil, 18.5x12ins (47x30.5cm), Kettle's Yard, University of' Cambridge, Cambridge.

FIG.6.15B. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Self' Portrait with Pipe, 1913, pencil, 18.5x12.2ins (447x31cm), Kettle's Yard, University of' Cambridge,

Cambridge.

FIG.6.16. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Three Women, 1913, Charcoal and wash, 9.25x7.5ins (23.2x1B.5cm). Reproduced in H.S.Ede, Life of Gaudier-Brzeska, 1930, as pl.LIV.

FIG.6.17. 1B.25x12ins Cambridge.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Woman and Dog, 1913, (46.4x30.5cm), Kettle's Yard, University of charcoal, Cambridge,

FIG.6.1B. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Vase, 1913-14, marble, 17ins (43.2cm), Ezra Pound Collection, Brunnenburg. Reproduced in Cole, Burning to Speak, as p1.45.

FIG.6.19. Bambala, Congo, Snuff Mortar, wood, 16ins (40.6cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1907.

FIG.6.20. 25xB.5ins Cambridge.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Garden Ornament 2, (63.5x47cm), Kettle's Yard, University 1914, plaster, of Cambridge,

FIG.6.21. Baluba, Zaire, Chief's Stool, wood, 21ins (53.3cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1905.

FIG.6.22. Illustrations of the possible process of development of Gaudier-Brzeska's Garden Ornament 2, by the author of this thesis.

FIG.6.23. 14.5x11ins Cambridge.

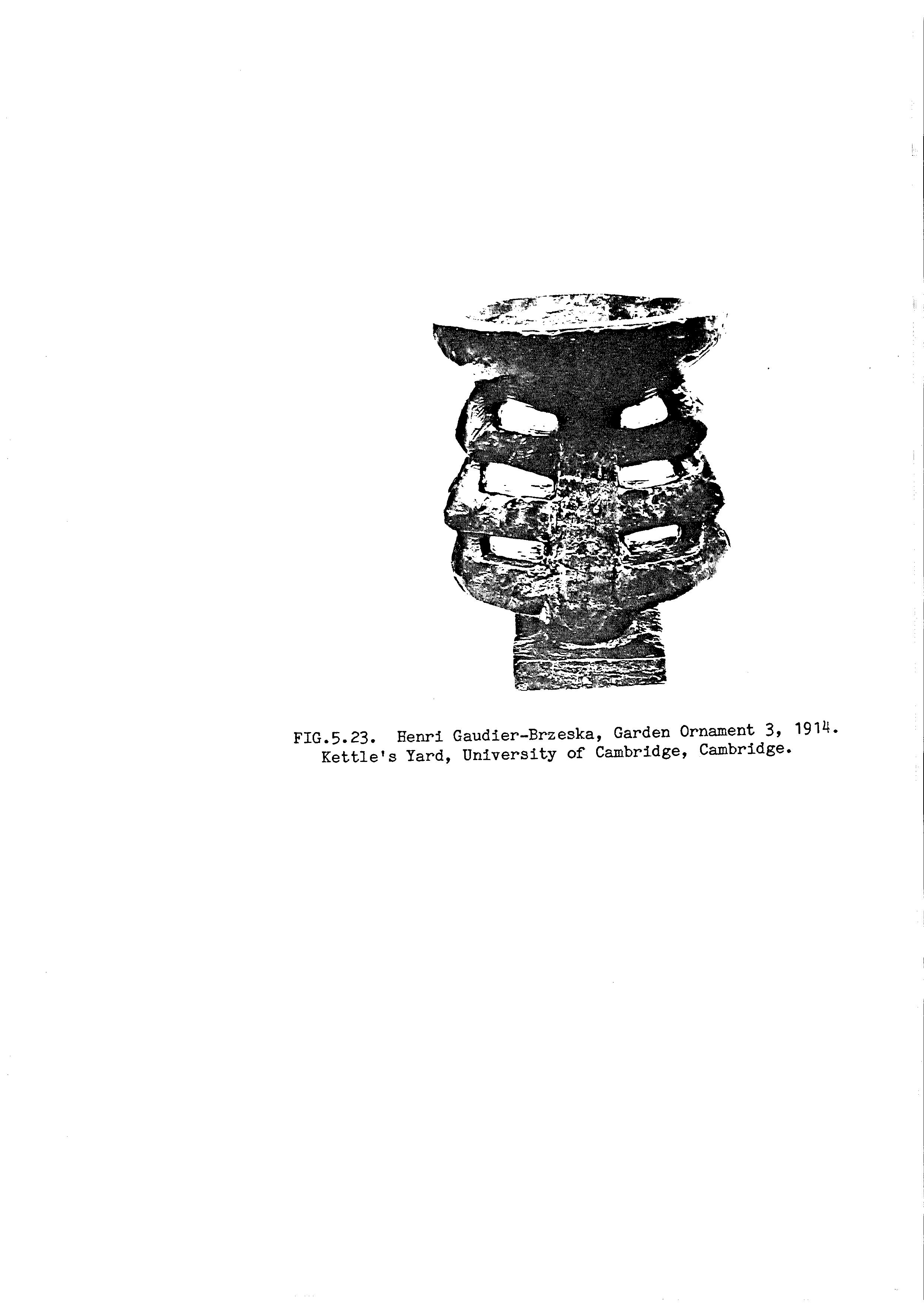

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Garden Ornament 3, (36.Bx27.9cm), Kettle's Yard, University 1914, plaster, of Cambridge,

FIG.6.24. Henri Gaudier-Brzeka, Men with Bowl, 1914, bronze, Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

FIG.6.25. Lozi, Zambia, Kneeling Woman with Bowl, wood, 22.25ins (56.5cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1905.

FIG.6.26A. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Design for A Door-knocker, 1914, ink and watercolour, 11.75x7.75ins (30x20cm), Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

FIG.6.26B. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Design for A Door-knocker, 1914, charcoal, 10.25x7.5ins (26.3x1B.5cm), Wolmark Collection, London.

FIG.6.27. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Door-knocker, 1914, brass, 6.Bx3.25x1.25ins (17.5xBx3cm), Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

FIG.6.28. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Couple, Q1913, ink and wash, size and provinance unknown. Reproduced in H.S.Ede, Life of Gaudier-Brzeska, London, 1930, p. 71.

FIG.6.29. Gaudier-Brzeska, Female Figure, 1914, ink, 1B.5x12.25ins (46x31.1cm), Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

FIG.6.30. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Hieratic Head of Ezra stone, 36x24ins (91.3x61cm), private collection, London. Cole, Burning to Speak, as pl. 50.

Pound, 1914, Reproduced in

FIG.6.31. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Maternity (front and back), 1913, marble, 11x10.25ins (27.9x26cm), Musee d'Art Moderne, Paris.

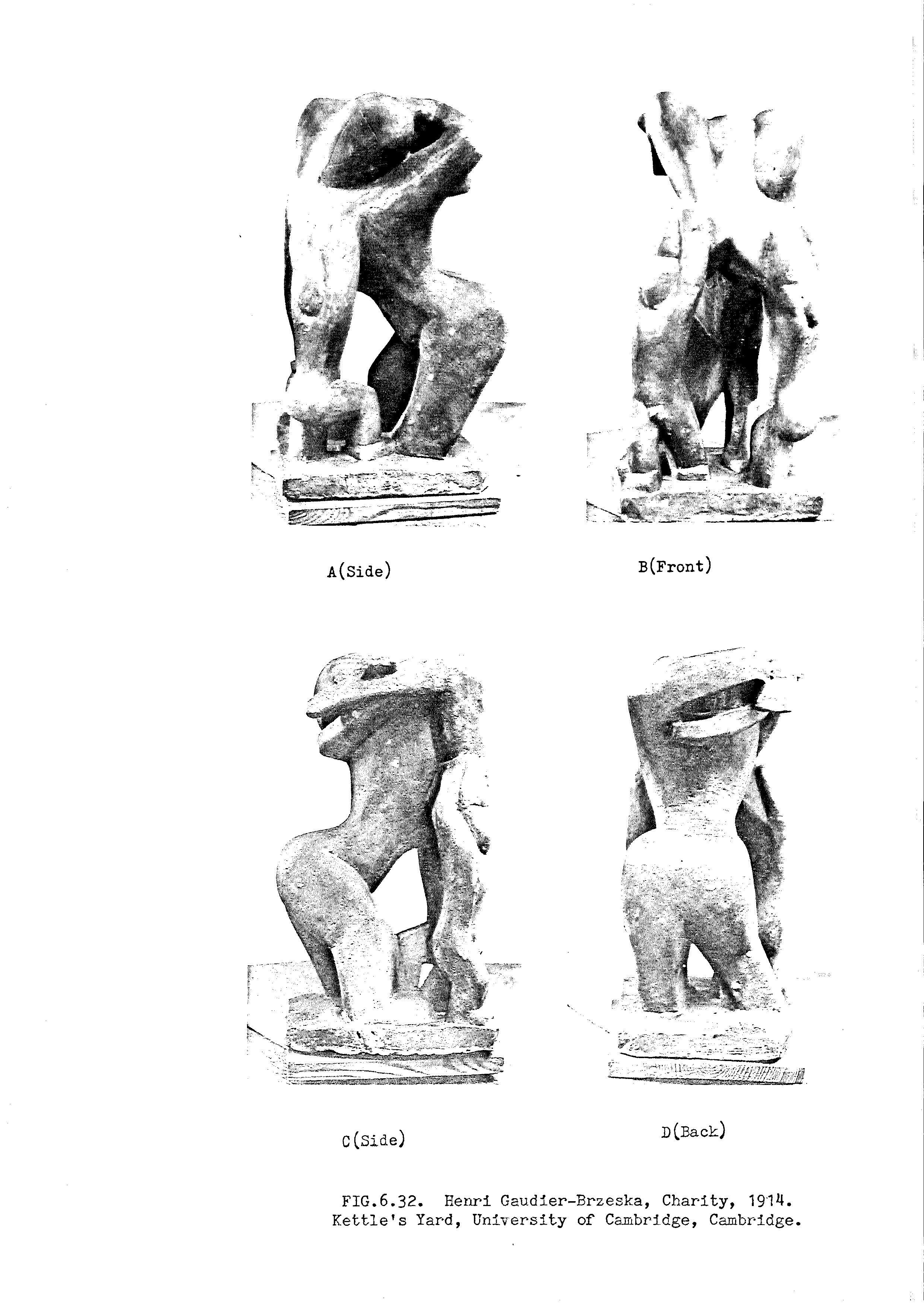

FIG.6.32. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Charity (front, back and sides), 1914, stone, 17.75x8ins (45.1x20.3cm), Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

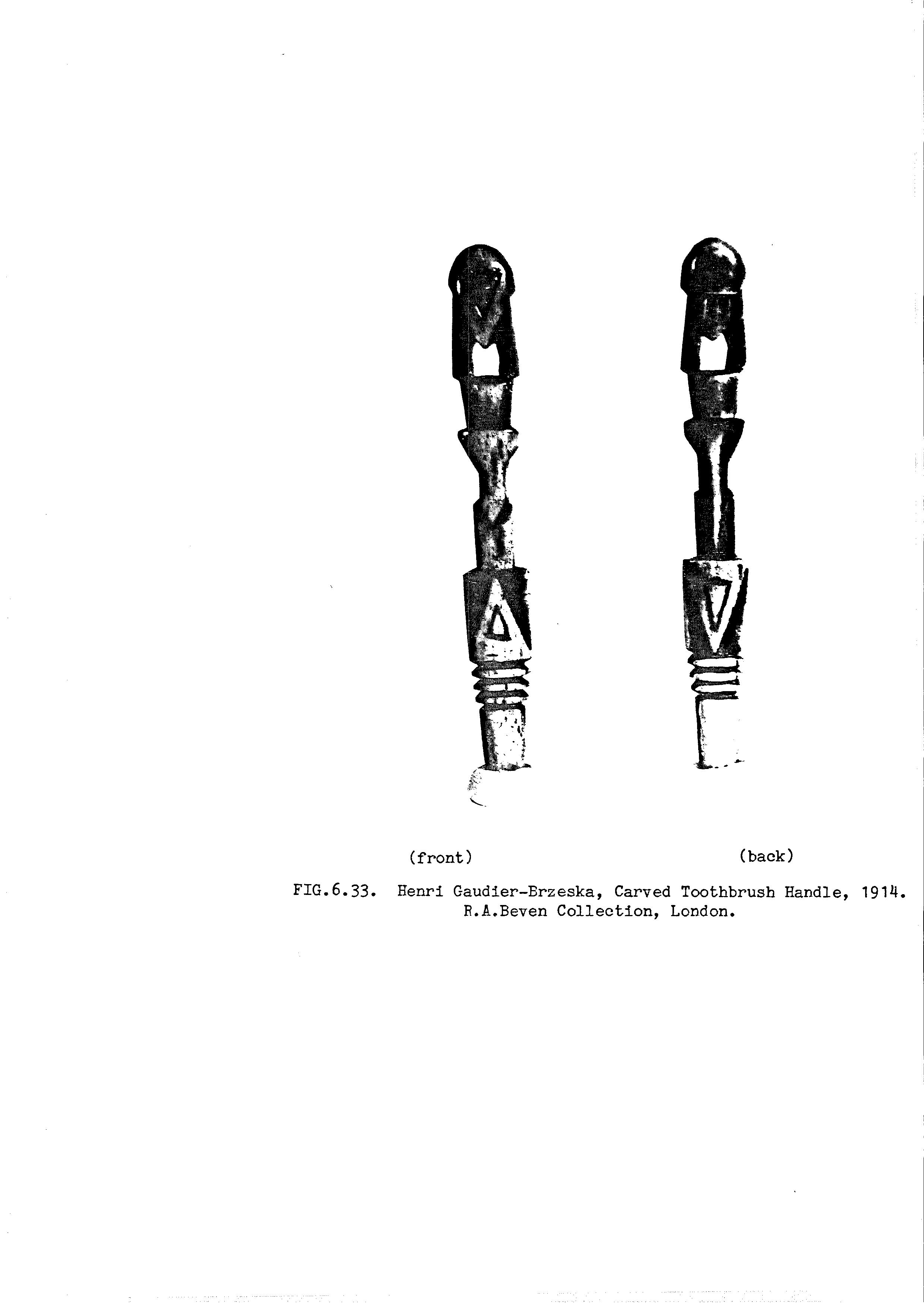

FIG.6.33. Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Carved Toothbrush Handle (front and back), 1914, bone, 6.75xO.8ins (17.2x2.3), R.A.Bevan Collection, London. Reproduced in Richard Cork, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age, London, 1975, p. 444.

FIG.6.34. Yoruba, Nigeria, Ivory Baton, ivory, 24ins (61cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1910.

fIG.6.35. Yoruba, Nigeria, Fetish Staves, wood, cane and metal, 58ins (147.5cm), 56 ins (142cm) and 52.25ins (140cm) respectively, British Museum, London, acquired 1903.

FIG.7.1. Baule, Ivory Coast, Seated Female Figure, wood, Paul Guillaume Collection, Paris. Reproduced in Roger Fry, Vision and Design, 1920, London, as pl.III.

FIG.7.2. Henry Moore, Head the Virgin (after Virgin and Child by Dominic Rosselli in Victoria and Albert Museum, London), 1922-3, marble, 21ins (53.3cm), Ramon Coxon Collection, London. Reproduced in David Sylvester, ed., Henry Moore. Vol.1, London, 1954, as pl.6.

FIG.7.3. Henry Moore, Studies for Reclining Figure (page 39 from No.3 Notebook) ,1922-24, pencil, 9x6.75ins (23x17.2cm), The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham.

FIG.7.4. Baule, Ivory Coast, Mask, wood, 25ins (63.5cm), British Museum, London.

FIG.7.5. Henry Moore, Ideas from Negro Sculpture (page Notebook), 1922-24, pencil, 9x6.75ins (23x17.2cm), Foundation, Much Hadham.

102 from No.3

The Henry Moore

FIG.7.6. Henry Moore, Sketches of African and Oceanic Sculptures (page 103 from No.3 Notebook), 1922-24, pencil, 9x6.75ins (23x17.2cm), The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham.

FIG.7.7. Junkun, Nigeria, Standing Male Figure, wood, 34.6ins (88.8cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1909.

FIG.7.8. Henry Moore, Sketches of Negro Sculpture (page 105 from No.3 Notebook), 1922-24, pencil, 9x6.75in (23x17.2cm), The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham.

FIG.7.9. Mumuye, Nigeria, Standing Female Figure, wood, 18.8ins (48cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1922.

FIG.7.10. Baga, GUinea, Head, wood, 24 ins (61cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1889.

FIG.7.11. Henry Moore, Head (page 126 from No.3 Notebook), 1922-24, pencil, 9x6.75ins (23x17.2cm), The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham.

FIG.7.12. Henry Moore, Drawings of African and Inca Sculptures (page 120 from No.3 Notebook), 1922-24, pencil, pen and ink, 9x6.75ins (23x17.2cm), The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham.

FIG.7.13. (18.4cm). Ubangi, Central African Republic, Negro Head, wood, 7.25ins Private Collection, New York. Reproduced in Carl Einstein,

Negerplastik, Leipzig, 1915, as pl.15.

FIG.7.14. Henry Moore, Sketches of Standing Figures (page 143 from No.3 Notebook), 1922-24, pencil and chalk, 9x6.75ins (23x17.2cm), The Henry Moore Foundation, Much Hadham.

FIG.7.15. Henry Moore, Studies of African and Eskimo Sculptures, 1931" pencil and chalk, 10.75x7.12ins (27.3x19.4), private collection. Reproduced in Rubin, ed., "Primivism", p. 602.

FIG.7.16. Henry Moore, Girl, 1932, wood, 12ins (30.5cm), private collection. Reproduced in Sylvester, ed., Moore Vol.1, as pl.112.

FIG.7.17. Nkole, Zimbabwe, Figurines, stone, 3ins and 4ins (7.6cm and 10.1cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1905.

FIG.7.18. Henry Moore, Head of a Girl, 1922, wood, 9.5ins (24.1cm), City Art Galleries, Manchester.

FIG.7.19. Henry Moore, Standing Woman, 1923, wood, 12ins (30.5cm), City Art Galleries, Manchester.

FIG.7.20. Henry Moore, Caryatid, 1924, stone, 12ins (30.5cm), private collection. Reproduced in Sylvester, ed., Moore Vol.1 as pl.17.

FIG.7.21. Henry Moore, Torso, 1927, wood, 15ins (38.1cm), Marborough Fine Art Gallery, New York. Reproduced in Moore Vol.1, as pl.47.

FIG.7.22. Azande, Sudan, Pipe-bowl in Human Form, wood, 11.8ins (31.2cm), British Museum, London, acquired 1860.

FIG.7.23. Henry Moore, Mother and Child, 1922, stone, 11ins (27.9cm), private collection. Reproduced in Sylvester, ed., Moore Vol.1, as pl.3.

FIG.7.24. Henry Moore, Maternity, 1924, stone, 9ins (22.9cm), Leeds City Art Galleries, Leeds.

INTRODUCTION

In 1935 a book of Hest Africa (Excluding Husic), edited by Sir Hichael Sadler, with an j.ntroduction by Sir \llilliam Rothenstein was published under the auspices of the Colonial Office in London, for the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures in London. It is a short illustrated book intended to be of service to those Ivho, in Britain and Overseas, are interested in the life of West Sir Hichael's own essay, I Significance and Vitality in African art f, also appeared in this book. Here, he briefly but effectively outlined the salient qualitties of African sculpture. He then pointed out that the sincere appreciation of African art by Europeans would take place only in the distant future. He therefore feared that the true recognition of the high merits of African sculpture vlOuld manifest too late or not at all because, liThe shado,;vs ax'e falling fast on 1.vhat is best in Hest African art."[1]

The indigenous religiOUS, economic, social, moral, political, and philosophical values that formed the cultural matrix of African sculptur'e was undergoing a fast and unprecedented change was undermining its significance and vitality. In order to arrest this unfortunate situation and to maintain a high aesthetic level of this ar·t form in it's native place, Sir Michael made a suggestion which began rhetorically:

vlhat then can be done? 'Send!, some may argue, I as soon as funds allow, to each British dependency in Equitorial Africa, and especially the west, an of outstanding capaCity who has shown insight into the significant quality of African art, and who can judge between what is good and ,vhat is indifferent or bad in it with a masterly penetration shown twelve years ago by Mr. Roger Fry vThen he lirote for the Athenaeum the memorable article on "Negro Sculpture", since published in his Vision and Design. '[2]

This artist of Fry's calibre was charged with several duties proposed by Sir Michael. He was to excite a general interest among Africans and Eur-opeans in the profound problems '\>Jhich implicated in the study of African art. He was to promote this art in African schools and to organise exhibitions in many places in the provinces, with a full explanation of the finest qualities in \'Jest African art. [3] Although there are indications of the appreciable success of this scheme, it has yet to be fully assessed. However, on the other hand, it can be claimed with a degree of certainty that there has been an increasing, sincere and discriminating appreciation and recognition of the vitality of African sculpture in Britain, Europe, and America since the first decade of this century. This is reflected in the high prices achieved by African sculpture in public auctions, in the acquisition programmes of Western museums and art galleries, in its indisputable and profound influence on modern art and its subsequent addition to the aesthetic vocabulary. Today numerous, well-illustrated, and at times colourful books, monographs, and essays on African sculpture are turned out each year. [4] From time to time major exhibitions of African sculpture are witnessed by the public in all the artistic centres of Europe and &'1lerica.

In Britain, in there have been no less than sixty major exhibitions of African sculpture since the beginning of this centur'Y. There rune over fifty private and public museums and galleries in Britain that have SUbstantial collections of African sclupture, (see Appendi.x III). No less than ten British artists, critiCS, decorative artists and so on have collected sculpture since 1912 to the present. It is impossible and needless to be statistical about numerous private individual collectors allover Britain.

The appreciation of the vitality of ,African sculpture in Britain had never been too late as Sir Michael feared. Britain can boast of scholars with deep 'insight' into African sculpture in the persons of i'lHliam Fagg, r-:lalcolm HcLeod, David Attenborough, Sir Herbert Read, Sir Kenneth Clark, Frank vlillet, Michael himself and others, whose appreCiations are often cited. The salesrooms in Britain are witnessing , and recording high prices and an increasing interest in prtmitive art, African and Oceanic sculpture in particular. London is the indisputable centre of the primitive market although New York is now the centre of American Indian objects. There are about 16 major sales of African and Oceanic sculptures in London every year. [5]

The leadership of Britain in this area is not fortituous. In the first place, Britain ''las a colonial pm'ler that had the most extensive trade links with several parts of fl£rica and by these links many ar'tefacts found their l'lay into Britain. In the second place, the leadership can also be attributed to the responsibility of a fevl British artists, critics and dealers who developed an aesthetic interest in African sculpture, admired, imitated, collected and evolved it, then developed a nevI connoisseurship in regard to it.

Paradoxically, since the discovery of African sculpture at the beginning of this century with its influence on Western art, its aSSOCiation with British art and artists in the process of modernization has not been stUdied. This phenomenon has been related to the French and German artists in PariS, l:'lunich and Dresden.

Of the several publications on African art only few included material on the relation of it to modern art. Robert Goldwater's Prim). tivism in Modern Art [6], is the most ci ted study in this area. It discussed the historical and aesthetic problems brought by

African and Oceanic art on modern painting, and related these problems to the French and German artists. It also discussed the influence on the works of Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska and Henry Noore as modern artists and not as representatives of the British school; except Epstein whose relation to Vorticism was mentioned in passing. The most recent publication "Primitivism" in 20th Century Art[7], edited by William Rubin, discussed the influences of many primitj.ve arts on 20th century artists in general, from Gauguin to Moore. African influence on Italian paitings, French, German and American art were also discussed excluding British art.

The reluctance of writers to discuss the crucial role of African sculpture on the British art scene could be attributed to the fact that the influence on British art is not a neatly self-defined phenomenon and great effort is needed to look into incidents that helped to realize it. For instance, the two Post-Impressionist exhibitions in London, the Pre-"lar conditions of art and the sudden and unprecedented prominence given to sculpture. And many writers on African and Oceanic influences seemed less concerned about them. The difficulties of analysing the complexity of British modern art in their essays has been epitomised by some writers. For example, Bryan Robertson stated: liThe difficulties of British painting during the twenties and the thirties are too complex to analyse definitely here ••• II [8]

There are other reasons for overlooking the role of the British school. The British were late to develop interest in African sculpture and were influenced by it at the time its impact on the continental artists, critics and 'iv-riters \Vas less dramatic. [9] In general the French were inspired by the formal quality of African sculpture and evolved Cubism, while the Germans were inspired by the sentimental impact of it and invented the Expressionism. [10] These approaches are distinct and

separate the two schools in the study of African influence on European art. The British were inspired by the formal quality after the French, but did not invent any African inspired movement to distinguish them. Another reason is that the British sculptors were prominently and for a longer period, influenced by African sculpture. But in the cases of the French and the Germans it was the painters. This seemed to be a disadvantage to the British because many writers on the subject concentrated on painting while sculpture was only occasionally mentioned. These reasons have more or less created the impression that the artistic scene in Britain was altogether barren of interest in African sculpture and its influence, although more went on in London than is often acknmvledged. Britain deserves in this area to be appreciated in terms of its own development in modern art.

This thesis seeks to investigate: how African sculpture has influenced the 20th century British artists between 1910 and 1930; to the what extent the artists influenced understood the conceptual foundation of African wood sculpture and if there is any need for such understanding in regard to the artistic development of the British artists.

The problems are: (i) To identify the formal qualities that characterised African sculpture which can be seen in the works of the British artists influenced by African sculpture. (ii) To identify the conceptual foundations and to see how and why the influenced British artists became interested in it and of what use it was to their development. (iii) To identify the problems aroused by the influence and to categorise the influence that affected the British artists.

The research is limited to 1910 and 1930 since this was the period of struggle for British artists to bring their- 1rlOrk to the level of those of their contemporaries in Europe, and it was the period in which the influence of African wood sculpture occured. After the 1930s the influence began to recede as a result of total establishment of or representational traditions which had been accepted in all variations as true means of expression; and the influence had been absorbed into the fabric of the history of modern art. The research is also limited to African wood sculpture and will not consider sculptures in stone, metals, ivory, terra cotta and other materials except for reference and except composite sculptures in which wood had been largely combined with other materials. It is difficult to deal with date of production and individual artists in regard to early African 1vood sulptures because most of them "Jere works of anonimity and the early collectors had no significant knmvledge of their production. Only very few of the wood carvings knmvn to us today are more than 150 years old and the majority are considered less. Generally African wood sculptures were shortlived in a tropical climate and in use. But in the case of the influence the dating can be limited to African wood sculptmnes that found their way into private and public museums and collections from 1800 to the 1920s in Europe, Britain, and tunerica that had been seen by the British artists directly or indirectly through illustrations. The actual ages of production of the sculpture and who produced them do not matter in the study of their influence but it is the date of their acquisition in Europe, Britain and America, and their provenance in Africa which matter. The research does not seek to establish the tribes in Africa whose sculptures influenced the British artists most because artists themselves ,,[ere not concerned with tribal styles and this is an independent study which is beyond the scope of this research.

The term African wood sculpture in this research refers to wood carvings of Africa, south of the Sahara, just below latitude 20 North of the Equitor including Madagascar, (see Hap 1), that conformed to ideas and practices established as valid to customs and beliefs of the African. The carvings therefore strongly adhered to styles, forms and functions determined by customs and beliefs. They are wood sculptures produced in the period long before European contacts with Africa and several decades after the contacts where European influence had not affected them due to the fast and unprecedent acculturation of the African continent. of these sculptures are found in European, British, American, Russian and African museums and galleries. Large numbers of them are also found in private collections allover the world. They are the works seen physically or through photographs and appreciated by the European and the British artists. Other terms used historically to imply African wood sculpture are: "Negro art"; "Negro sculpture"; "African Negro art"; "African art"; "Black African art"; "Tribal art"; "Traditional tribal art"; and "Primitive art". Although many of these terms are unSUitable terminology, it is not necessary to redefine them here but they will be used in a context of African wood sculpture. On the other hand the term African art shall be used in broader sense to cover architectural decorations, design works, pottery, jewellery, textile and other African artefacts. For the matter of simplicity the term African sculpture shall be used throughout this thesis.

The term Primitive art will be used in broader sense to cover sculptures of Africa, Pacific Islands, North Indians, Eskimos, etc.

Conceptual foundation is a term that refers to the concepts that formed the basis of African art. The concepts refer to factors like meaning, form, style, motivation or inspiration, aspiration and functions which determined the goals and manifestations of artistic expressions which in turn culminate in the cultural totality or complex.

The procedure here is to use the most up-to-date names if

Due to several field studies of African art tribal names have changed. possible.

The first assumption in this research is that there are visible influences of African sculpture on some 20th century British artists. The second is that the British artists influenced by African sculpture did not initially understand the conceptual foundation of African sculpture although in the later years their writings reflected a limited contextual meaning of the sculpture. They were irrelevant to their critical studies of the formal qualities and their modern artistic development. The third and final assumption is that the extent and nature of the influence can be determined through the study of works, pronouncements, writings, and publications of and on some 20th century British ffi1 tists and critics.

The paintings and sculptures of the British artists that show African influence are studied in comparison with the African sculptures that are supposed to influenced them. Examination of brief but revealing explanations and views on African sculpture and the subtle revelations of methods and meanings of the artists are made. The first four chapters deal with the factors that contributed to the manifestation of the influence. The last three chapters consider three British sculptors as case studies. The first chapter deals with the analysiS of the formal qualities of African sculpure. It establishes

the generalised formal characteristics that interested the British artists and influenced their drawings, paintings, sculptures and tastes. The second chapter states how the British artists became interested in the conceptual foundations of fl£rican sculpture. It explains these foundations by discussing the motivations, functions, purposes and sometimes the meanings of the works and explains to what extent these foundations were understood by the British artists and how little they were related to their artistic development. In this chapter P£rican sculptures in many museums in Europe and the United States of America are cited to illustrate points. This does not mean that the British artists had seen them. Chapter three deals with how African sculpture was introduced into Britain and how the ethnographic and the aesthetic interests were developed in it. It examines how it came to influence the works and tastes of British artists. Chapter four discusses the artistic problems posed by the influence, the misunderstanding of the term influence. It examines some previous definitions of the term and then redefines as well as outlining types of influence that affected the British artists. Chapter five discusses the passionate and obsessive approach of Jacob Epstein to African sculpture, his interest, writing and collection of it. And how his drawings and sculptures were influenced by it. Chapter six discusses the experimental approach to African sculpture by Gaudier-Brzeska, and hmv and to what extent his sculpture and drawings and taste were inlfuenced. Chapter seven deals with how Henry Moore derived his inspiration from African sculpture and how it influenced his works and then led him to other forms of SCUlpture.

Although this research does not claim to exhaust the study of the subject it will hopefully serve as documentary evidence of the influence of African sculpture on 20th century British artists. As a body of

knmvledge the result of this research will be useful to other researchers in Art History, anthropology and other related fields of knowledge.

FORMAL ANALYSIS OF AFRICAN SCULPTURE

African sculpture is usually approached in terms of its purely formal or plastic characteristics and the way they have been organised. For instance J.J. &,eeney considered that the plastic qualities manifested in African sculpture were unrivalled:

It is not the tribal characteristics of Negro art nor its strangeness that are interesting. It is its plastic qualities. Picturesque or exotic features as well as historical and ethnographical considerations have a tendency to blind us to its true worth... It is the vitality of Negro art that shOUld speak to us, the simplification without impoverishment, unerring emphasis on the essential, the consistent three-dimensional organization of structural planes in architectonic sequences, the uncompromlslng truth to material... The art of Negro Africa is a sculptor's art ••• It is as sculpture we should approach it.[1]

&veeney epitomises the way British and European avant-garde artists approached African sculpture as SCUlpture. It was the formal characteristics which attracted and influenced them and sustained their visual interest. They were not initially interested in the subject matter nor any ideological content that African art possessed. It was a few years later that some of the artists began to develop interest in these areas. By analysing the basic qualities of African art, (the forms, surface treatment, and organisation), it is possible to understand and indentify the nature of the visual stimulus that the avant-garde experienced. Yet some scholars are still uncertain as to how far the formal aspect can be separated from the content of African sculpture or primitive art in general for a meaningful aesthetic appreciation. Eckart von Sydow believed that, "to separate the object from its social significance, from its ethnic role, to see and look for aesthetic side alone is to remove from these specimens of Negro art

their sense, their singnificance and the reason for their existence."[2]

This Chapter concentrates on the formal aspects since initially it was only these that interested the avant-garde. As William Fagg, one of the foremost authorities in the field of African art, confirmed when he wrote: "What interested and influenced the 20th century avant-garde was the pure form of African carvings; they knew nothing of the meaning of the forms, of their content of their belief, and cared less, for among their revolutionary purposes was the liberation of form from content in art."[3J

The formal analysis here is based upon selective generalization arrived at from the author's observation of African sculptures in museums in Britain, and from the results of field-studies by other writers. Some writers are reluctant to make general statements about African sculpture because it is so diversified and covers such a vast area which according to them is not homogenous. For example Andre Terisse argued that, "it is very difficult to classify or to generalise in the domain of African art."[4] Other writers, such as Werner Gillon believed that in spite of the stylistic diversity there are certain common characteristics in the treatment of forms and masses in most African sculptures, wherever it originated.[5J Fagg also accepted generalisation in African sculpture on broader terms in relation to art in general. [6]

African sculpture largely consists of human figures and masks; comparatively few animal were carved. The formal analysis of the human figure is divided into two sections: - Major Forms (the head, the neck and torso, and the limbs); Minor Forms (the eyes, nose, lips, ears, the female breasts, the navel, the forearms, the fingers and toes, the buttocks, and the male and female genitals.)

African figural sculpture .vas alvTays divided into three parts and the most striking characteristics of the figure is the disproportionately large head. This usually forms one-third of the total height of the figure. For instance, the Female Figure, FIG.1.1, Baluba, Zaire, acquired by the British Museum in 1910, has a large head vlhich is approximately one-third of the total height of 18ins. (46cm). This intriguing and unusual proportion is known as 'Reducing Proportion', 'Diminishing proportion', 'Proportion of Significance', or 'African proportion'. In his analysis Jan Vansina explained that the head forms one-third or one-quarter of the total height of many African figural sculputres. He illustrated this with a diagram, FIG.1.2, which is based on Louis Perrois's analysis of over two hundred Fang statues. [7] The numbers in the vertical order the percentages of the parts to the whole figures. In accordance with thiS, it has been argued by iHllet that, in general, sculptors traditionally began by carefully dividing the block of wood to be carved into separate sections which would eventually represent the head, body, and legs. Hence these proportions deliberately established at the outset. Robert Hottot first observed this as early as 1906, although his work was only published posthumously in 1956.[8] FIG.1.3 shows the various stages of carving: Diagram 1 represents the cylindrical log of wood to be carved; Diagram 2 shows the first stage of cutting away of the round surface to give the vlOod flat planes to make it more stable and easieln to grip as it is worked by the sculptor siting on the ground or on a low stool. One end is held in one hand the other end stands on the ground. The tool is held in the free hand. Sometimes the wood is worked on the ground on its side, where it \vould roll around out of control if it vias not cut into planes.

In Diagram 3 the block is divided into sections establishing the proportions. The three brackets and the corresponding sets of numbers indicate the three primary divisions and proportions. The horizontal lines indicated by the second, fourth and fifth arl"OV1S represent the secondary scorings which guide the carver to fit the various parts of the body into the format of the wood; Diagrams 4 and 5 ShOVl the wood rudimentarily shaped in accordance with various parts of body, while Diagram 6 shmis the completed figure. [9] The practice of giving figures large heads is often attributed to the fact that the African regarded the head as the seat not only of intellect but also of the emotions. The sculptor stressed its importance by exaggerating its size. Leon Underwood explained that, "The head, regarded as the seat of all human wisdom, is a symbol the meaning of which, in Europe, belongs to the heart. ,,[ 1 0] There are a feo,r exceptions to this general rule vlhere the proportions of the heads to the bodies are in the ratio of 1:5 for example in the Female Figure, and even 1:12 as in the Staff, Mbuun, (See FIG.1.4)

Apparently thepe is no specific established shape for the head which is common to all African sculpture. The head may be egg-shaped, conical, pyramidal, oval or squarish. In some cases the treatment of the hair makes the head larger and defines the form. FIG. 1.5 illustrates examples of different head types. They are all geometriC in shape, ie. they are all based on cones, spheres, half spheres, cubes, pyramids, or combinations of these (eg. FIG.1.5E) Another common feature is the prominence given to the forehead i'lhich may protrude dramatically in a dome-like sweep or form a horizontal shelf-like overhang as in FIG.1.5E. Often the prominent forehead gives a prominent concave profile to the face as in FIG.1.5C.

Generally speaking there are two types of faces in African sculpture, namely, the concave and the convex faces. In the concave faces the dome-like foreheads and the depressed bridge of the noses form a'S' curve in the profile, while the shelf-like overhang forms a 'C' curve. In the convex face the sweep of the forehead continues downwards with the nose without any depressions forming a bow. (See FIG.1.5D)

Douglas Fraser, Lavachery, Perrois, and Hans Himmelheber have all observed that the two types are equally common and can be found in the same tribe and place. Himmelheber stated: "Probably no tribe is destined by nature or by some inherent aesthetic to carve in one manner and not in the other(sic)."[11] As an example he cited the Senufo, whose works are generally concave, but who occasionally produce convex pieces. He identified three geographical regions where the concave tendencies predominated: the Sudan (the Senufo, Bambara, and Bobo tribes); the area between the Lower Congo and the Ogowe Rivers (the Bakota, Pangve, Bapende, Bakwele, and Ossyeba tribes); and the Eastern Congo (the 11bole, Hetoko, Balega, Babembe, and Baluba tribes). Yet he also emphasised that in these regions there were tribes producing convex pieces. For instance in the western Sudan, the ¥asage, Pumi, Benjabi produce convex 'ivorks. Outside these regions both tendencies equally common. Map 2 shows the Regional Distribution of Concave and Convex Faces. 11ap 3 gives more detailed positions of the tribes. Fraser and Lavachery linked the concave tendencies to the survival of the oldest Black Cultures, the 'paleonigritique' [12] Fraser explained that 'paleonegritique' is an African prehistoric culture of the Neolithic period often referred to as Hegalithic tradition which is 5,000 years old. This tradition is similar to those of Europe, Hiddle East and Asia. He therefore observed that the concave motif is in several art styles of these periods and traditions. He cited examples

of Hegalithic ivory figurines with concave faces excavated near Beersheba in Palestine, in Scandinavia and in the Urals of Russia in comparison with two wooden grave effigies excavated in South Ethiopia now in the Sammlung flir Volkerkunde, University of Zurich. [13]

Another characteristic of the face that has been by some writers is the 'heart-shape'. The term 'heart-shaped face' was coined by Paul Wingert. [14] Elsy Leuzinger described the face as having I high-arched eyebrows, s,V'eeping outward across the temple and cheeks, and meeting at the mouth'. [15] Fraser considered it a complex idea that runs through African sculpture and elaborated:

••• the face is shown as a smooth depression or concave face which extends from the under side of the eyebrows to the vicinity of the mouth. Within the heart-shaped plane, the nose appears in a relief as a downward extension of the forehead and the eyes as raised oval shapes.[16]

Edna Bay divided the heart-shaped faces into six types, (see FIG. 1.6). In the first type, the strong arch of the eyebrows ends in a pointed or rounded or rectangular chin. This shape is commonly found among the works of the Bakota, Mpongwe, and Fang tribes; the Baga, Senufo, Baule and Kissi in the west; Ibibio, Ibo, Ijaw, and Ijala in South Nigeria; Bapende, Ndugu, Balega, Bene Lulua, Balubu, and Bakuba in Zaiere; Ometo in Ethiopia; Zaramo, Yakonde and Zulu in the east and south. In Type 2, the heart-shape ends in the upper or lower lips, ie. the lower or the upper lip forms the base of the heart shape; for example a Bala'lele mask 't'lhere the heart shape ends in the upper lip, (see FIG.1.7A); and a Bakete mask with the lower lip forming the base of the heart shape, (FIG.1.7B). Figures and masks with the heart-shape ending in the lower lip are less common and often found among the Fang, Barega, and the Makonde. Those with the heart shape ending in the the upper

lips are common to the Baule, Afo, Ibibio, Ekoi, lbo, Ometo. In Type 3, the archs of the brows meet the rectilinear edges of the cheeks which formed a V-shape. This is common among the Bakete, Barega, Bapende, and Bakuba. In the fourth type the concave plane of the face is very shallow. The intersection of this plane and the planes of the jaws forms a rounded ridge, unlike the sharp ridges of types 1 and 2 faces. It is frequently found among the Baule, Guro, Fang, Dan, Bapunu, Baluba, 11akonde, Balumbo, Bapende, Basuku and Senufo. In Type 5, the brows descend in steep diagonals to meet the edges of the cheek and form a diamond-shape enclosing the concave plane of the face. This is common among the Barega, Dogon, Baga, Bakota, Baluba, and Ngombe. Type 6 is characterised by a straight and strongly emphasised forehead which overhangs the lower face, replacing the arched brows. The chin can be either rounded or pointed, but the face is often elongated. Although this type hardly looks heart shaped, Professor Bay considers it to be an adaptation of the long shape of Type 1. It is common among the Toma, Dogon, Bobo, Mende, Baga, Bambara, Malinke, Senufo, Dan Ngere, Ijaw, Ibibio, Bakota, lbo, Ngumba and Duma. Type 1 and 2 are the most common and Wide-spread, while Type 5 is the least common, (see r1ap 4). Apparently, the concave and the heart-shaped characteristics are inseparable. Their meaning and functions are still obscure. Fraser thought that the origin of the concave trait might be at least fifteen hundred years old, from the time of the beginning of the migrations by the Bantu-speaking peoples whose ancestral roots lie in Nigeria. [17]

Owing to the emphatic use of geometric shapes, planes, and sharp and rectilinear edges the face is often devoid of emotional expressions such as joy or anger. The face is mute and impersonal and this invokes a feeling of tranquility (perhaps induced by a trance-like state), serenity and dignity. These characteristics were to remind or

reassure the African of the peace and har'ID.ony the physical and the spiritual world which necessary for his survival. [18] However, there are some sculptures that display rather threatening features: glaring eyes and rows of aggressive teeth revealed through square or oval mouth, (see FIG.1.8). Perhaps they were to invoke a sense of fear or humour in the onlooker.

In spite of the generally stylised treatment of facial features in African sculpture there is some evidence that there have been attempts to carve portrait statues or portrait masks among the Bushongo, Baluba and the Baule. These are, not portraits in the European sense, intended to convey a reasonably accurate likeness of a specific person at a particular moment. African portraits are conceptual, not visual, representations of the individuals. In other "lOrds they have the same formal characteristics as other sculpted figures but with the difference that they are commemorated to, or associated with specific individuals. The examples most frequently cited are the Baluba figures or Ndobs, which commemorated the kings of the Baluba people of Zaire,(see FIG.1.9). The earliest of these been dated to about 1600.[19] The almond shaped eyes with horizontal slits are closed probably to emphasise the repose of the dead king. It shows a huge head; thick cylindrical neck; square shouders; short arms with blunt fingers; and cross-legged posture. Such characteristics are found in other figural sculptures except perhaps the cross-legged posture.

The Baule portraits also depicted imaginary individuals living in the ancestral world or heavens, to elicit their protection for the living owners. They were associated with the Baule belief that every human being lived in Heaven before they "Iere born. Since the earthly spouse was not necessarily the heavenly spouse, the latter might appear in a dream. Then the heavenly spouse was described to the sculptor who

made the portrait. [20] Such portraits were characterised by the heart-shaped motif, sl it eyes, long narrO',i inverted ! T I shaped noses, pursed lips, rounded chins, and dome-shaped foreheads. The cheeks, the temples, the necks and at times the chins were decorated vlith cicatrices in 10Vl relief. These were tribal marks of identification which have now lost their meaning.

The second section of the African sculpted figures comprises the neck and torso. The neck is often cylindrical and elongated; it seems to be the extension of the torso '-lith relation to the thickness of it. In other words the thickness of the torso often determined the thickness of the neck. This trait is well depicted in FIG.l.l0 Standing r-hle Figure, Basongye, Zaire, in the British Huseum since 1908. The torso is often cylindrical with occasional bulges at the front as in FIG.l.l0, or at the left and right sides, giving it slightly conical or pyramidal effect. These bulges sometimes were to facilatate holes in the torso in which magical substances were stuffed. In such cases they are described as Fetish Figures. The Female Figure, Dogon, FIG.l.l1, acquired by the in 1906, shows an unusual type of torso that is flattened on both sides. This is a common feature of the ancestor figures of the Dogon.

The Lmier limbs form the shortest section of the body; the thighs and legs are short and often thick, the feet are broad and either flat or pyramidal. Guillaume observed: "Such legs and feet are characteristic plastically like stability. It [21] of nearly all sculpture ••• They function the base of a pyramid to serve fundamental

Besides the structural significance of flat or broad or pyramidal feet as a support and balance to the figure, Fagg suggested that it symbolised man's faith in a stable universe and his intimate relation to Hother Earth. [22]

The knees are often bent to give a zig-zag impression to the lower part of the body. Andreas Lommel assumed that this was derived from squating figures but the actual origin and meaning were unknown to him. [23] Ladislas Segy interpreted the bent-knee as a restrained posture and therefore called it 'latent motion'. [24] There are, however, several African \'looden figures with relatively straight legs. A Female Figure, Hende, (FIG.1.12, which was acquired by the British Nuseum in 1908), from Sierra Leone has straight long legs but disproportionately small, short, and weak arms. The figure is blackened and it is used by the Yassi, a society devoted to the art of magical healing. It is supposed to trasmit the wishes of the spirits through the medium of the shaman priestesses. [25] The head is approximately one-sixth of the height46.25ins (117.5cm). The unusual proportion Cnot of the usual African proportion) and the straight legs of this figure cannot be attributed to its magical significance.

The Hinor forms or secondary anatomical features such as the eyes, the nose, the breasts, the toes and fingers, the navel, the buttocks the genitals, etc., can be considered to be the most expressive parts of African figures and masks. As well as expressing mass and volume, they are also sometimes decorated with symbolic details, the significance of most of which are obscure.

Eyes carved in an immense variety of forms. They may be incised or projecting almond shapes, coffee beans, or mere horizontal slits either straight or curved, and or sometimes they are gouged out like craters. In some masks and a few figures, the eyes are square, rectangular or diamond shaped holes. Sometimes they project in high relief as cylinders, cubes, pyramids, and cones. They may be tiny or disproportionately huge, close together or wide apart.

FIG.1.13 illustrates different Eye Types:- Type Al, is a raised lozenge shaped eye with a dot for the pupil; A2 has incised lozenge shape eyes. Type B shows almond shape eyes (B1 is concave, B2 is convex). Type C shows slit eyes: diagonal slits, horizontal slits, and curved slits. Type D are conical projections. Some have pointed ends and others rounded tips. Others are prisms. Type E represents the pierced eyes: round, square and cut out horizontally or vertically. Type F are cylindrical eyes without holes and with holes like tubes. [26] Type G consists of eyes represented by other materials such as seeds, metal discs, shells or pebbles. For instance G1 shows eyes represented with cowry shells. All of these varieties of eye shapes are found among the works of all the different tribes.

The nose may be thin or thick, long or short; a triangle, an inverted 'T' or a rectangular block. In most cases the nose represents the continuation of the forehead. In concave faces the nose is dramatically depressed at the bridge. FIG.1.14 shows the different Nose Types:- A is a pointed and up turned nose which is commonly found on Bayaka and Basuku figures and masks. It is usually described as the nose of Cyrano by some writers. [27] Type B is a long triangular nose in high relief. Triangular noses are the commonest type of nose found generally in African SCUlptures. Type C is a huge projection with the base shaped like an arrow head. It is common to Baga SCUlpture. It is believed to symbolise the phallus, fertility and fecundity. [28] Type D, the inverted 'T' shaped nose is common among the Baule. Type E, is used by the Basuku, Baluba, Bakuba and Yoruba. Type F is the long and sharp ridge nose which anticipates Modigliani's sculptures and was used by the Dogon, Guro, Senufo and Baule.

Other features shOiv an equal range. The mouth could be oval, almond, or diamond shaped, rectangular tube, (see FIG.1.15, eight-shaped or Mouth Types). even a circular or The ears often carved as horse-shoe, saucer, or cup shaped, (see FIG.1.16). The arms may be straight or curved cylinders; attached or detached from the torso. The way in which the arms are joined to the torso makes the shoulders square and vital, or rounded and drooping. The hands are usually less carefully treated with tube-like and blunt fingers, although among the Bajokwe of Angola, the hands and feet are carved with great care and detail, the finger and toe nails, (see FIG.1.17, A Figure, Bajokwe). It represents the ancestral hunter and warrior Chibinda Ilungu holding his gun and staff in hands and ,vearing an elaborate hat of a chief. The size of the hands and feet suggest physical strength and endurance. Their elaboration emphasises their importance to a warrior and hunter. [29] The arms may be raised above the shoulders to support an object placed on head as in caryatids.

The female breasts are usually depicted as large or small cones which are placed high on the collar bones, at right angles to the body. They may also be spherical or cylindrical thrusting horizontally or downwards. Sometimes they are represented as by the inverted two sides of a triangle in high relief, (see FIG.1.18). The navel is often represented with a small or a large plug or cone, or even a small rounded form like a boil. It generally expresses the link betiveen man and his physical and spiritual origin and his unshakable attachment to nature. [30]

The buttocks are usually rendered as masses jutting out to counterbalance the thrusting breasts and the slightly bulging stomach at the front. The backvlards thrust of the buttocks sometimes creates a strong curve at the back of the torso.

The male and female organs are sometimes exaggerated and shown in an uninhibited way. The penis, for instance, may be elongated to the level of the knee or the shin. It may also be a roughly shaped, horizontal, diagonal or downward pointing appendage. The testicles are less prominently represented, usually being shown as two small balls attached to the sides of the penis at the base between the thighs, (see FIG.1.19). The scrotum sack occasionally as a hernia. In the first three figures of FIG.1.19 the penis is elongated and it is almost as thick as the legs. The position and size of the penis in relation to the body and the legs were determined by aesthetic and material considerations. A penis of such length and size would easily break off in wood if positioned horizontally, and it would also introduce a strong element of horizontality which would break the vertical rhythm of the figure. The exaggeration is often adjusted to the overall structure of the statue. In the female figure the pubic triangle is emphatically broad and occasionally covered with cicatrices as seen in FIG.1.1. The vagina itself is at times represented by or inverted little isosceles triangle, a vertical slit or an apperture. It is sometimes rendered open in an attempt to show the internal details. The clitoris and the libia are sometimes seen grossly protruding and parted in the middle. FIG.1.20 shows a figure with a protruding sexual organ with cicatrices covering the pubis and the stomach and hands resting on flat triangular breasts. FIG.1.21 shows a vertical slit representing the sexual organ and small conical breasts; FIG.1.22 shows a figure with a small triangle for the vagina; and FIG.1.23 shows a female rider carrying a huge bowl. Her vagina is a large round and deep hole. The overt display of the sexual organs is an acknowledgement of their procreative powers. Such figures were associated with fertility rites, and were not directly aimed at sensuality or eroticism. [31] R.H.Wilenski stressed:

There was sexual meaning in Negro sculpture but not sensual meaning. Even making the maximum allowance for the known and presumed differences between the white man's and the black man's erotic, it seems impossible to assume that the caressibility was a character that the negro sculptors were mainly concerned with in their rendering of the naked human body. [32]